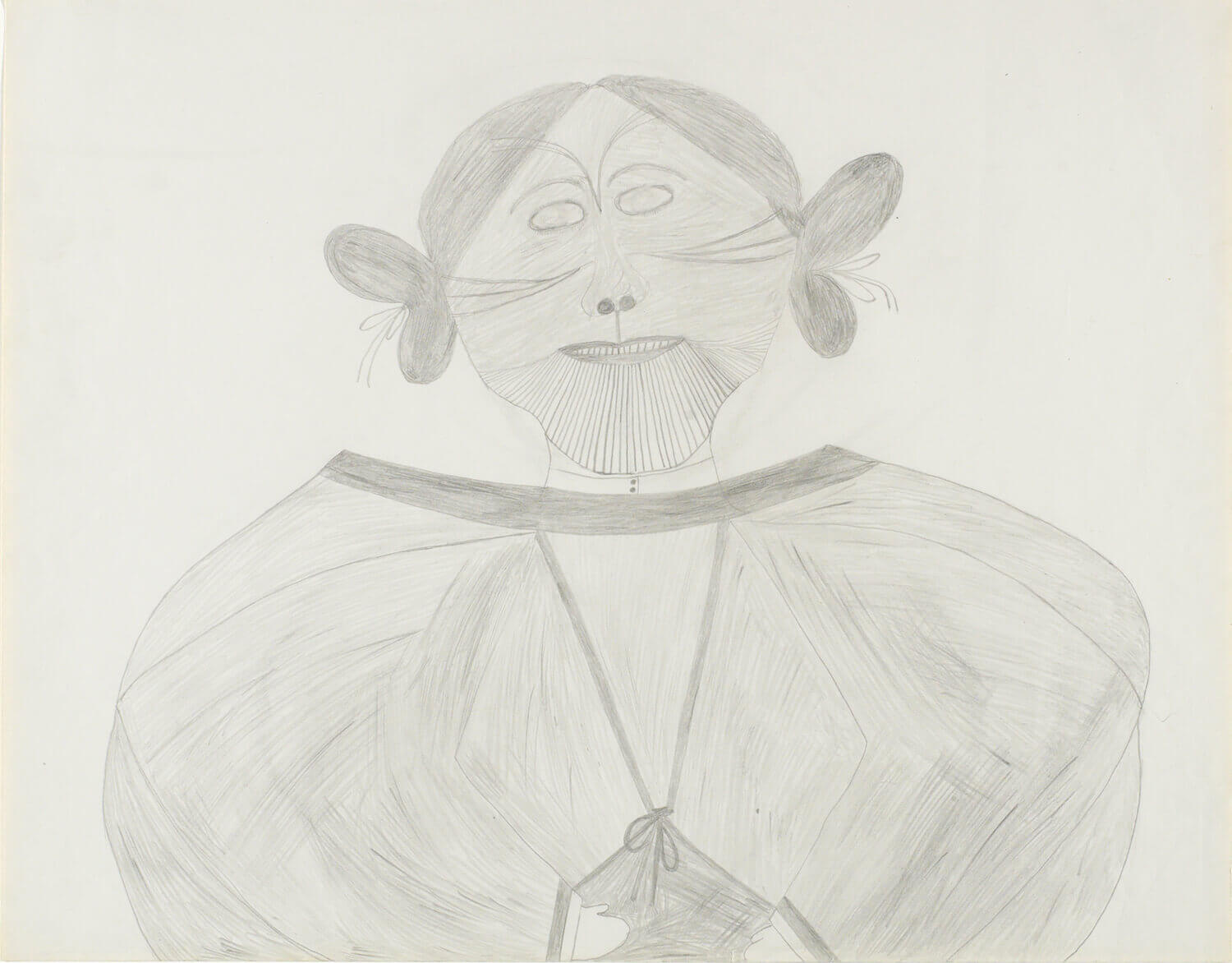

Tattooed Woman 1960

Pitseolak Ashoona, Tattooed Woman, 1960

Graphite on paper

41.9 x 53.4 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

By 1960 Pitseolak had already developed a level of confidence in her drawing, evident in this depiction of an Inuit woman with facial tattoos. She wears an amauti, a woman’s parka with an extended hood in which a young child can be carried, nestled against its mother’s back. With fluid lines, the artist conveys the bulky curves of the amauti as well as details—the complex ties across the front, the elaborate braided hairstyle, and the intricate facial tattoos.

Inuit in different regions, and even within communities or family groups, have their own style of amauti. The overall form of the garment and the linear patterns, usually in alternating bands of dark and light, have long been a source of pride for Inuit women. Even the thinnest decorative bands must be both wind- and waterproof. Pitseolak was known for her exceptional sewing talent; having prepared the double-layer skin clothing for her family season after season, she had an intimate understanding of both the function and design of the amauti and was able to depict it concisely in a few drawn lines.

The amauti is deeply symbolic of motherhood, a valued role within Inuit culture. Pitseolak captures the sense of a mother’s all-encompassing care in the way she emphasizes the full roundness of the hood and enfolded arms. Facial tattoos mark a woman’s maturity, accomplishments, and place in Inuit society. Pitseolak recounts that her mother, Timungiak, had tattoos and describes how the marks were made with soot and caribou sinew. According to Dorothy Harley Eber, whose interviews of the artist form the basis of Pictures Out of My Life, she later identified the woman in this image as her mother; Tattooed Woman can be viewed as an homage both to her mother and to Inuit women of earlier generations.

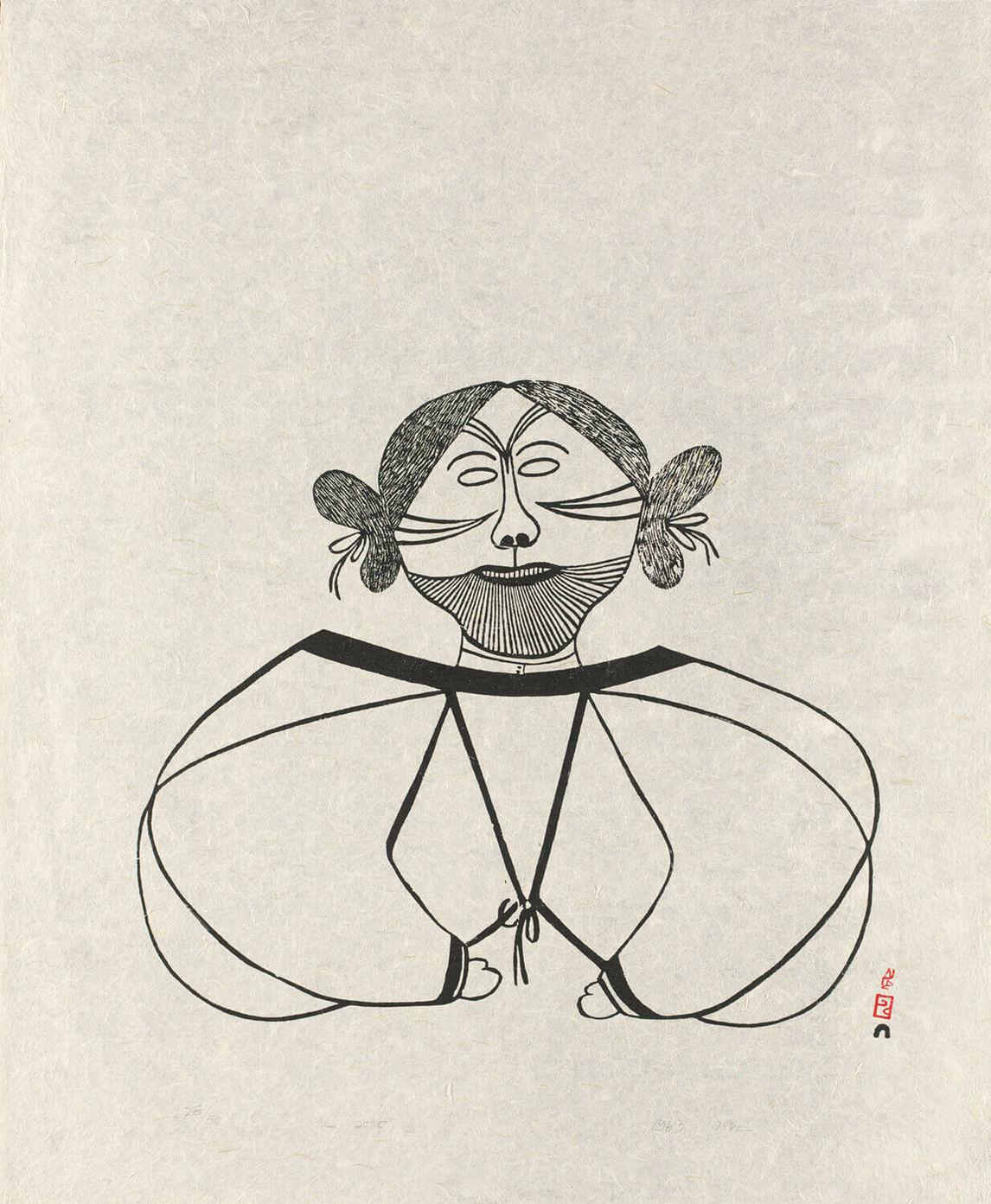

Lukta Qiatsuk (1928–2004) translated Pitseolak’s drawing into a stonecut print, retaining its crisp black and white imagery. It was published in the 1963 Cape Dorset annual print collection as Tatooed Woman; subsequently, it often appears in catalogues with the title spelled this way. As one of her earliest prints, made from a graphite line drawing and not yet indicative of the lively character for which she would later be recognized, this elegant image is nonetheless one of Pitseolak’s best known and has become an icon of Canadian art.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements