Kiss & Tell’s artworks were grounded in societal issues, including the feminist sex wars, the censorship of queer art in Canada, and disability. They used humour, photography, writing, and performance to bring attention to lesbian identities and sexual practices. The collective questioned the ethics of pornography and asked whether a line can be drawn between art and erotica. They focused not only on queer subject matter but also on queering the act of viewing by providing interactive spaces for audiences to respond to what they were seeing.

The Feminist Sex Wars

The feminist sex wars of the 1980s and 1990s involved two opposing groups: the anti-pornography camp and the sex-positive camp. The former argued that all pornography objectified women and led to male violence against them, while the latter argued for the “primacy of pleasure theory”—the idea that sexuality can be an exchange of physical and genital pleasure rather than simple intimacy and bonding. The sex-positive camp also opposed obscenity laws, censorship, and measures that restricted sexual expression. Sex-positive feminist writer Gayle Rubin argued:

The women’s movement may have produced some of the most retrogressive sexual thinking this side of the Vatican. But it has also produced an exciting, innovative, and articulate defence of sexual pleasure and erotic justice. This “pro-sex” feminism has been spearheaded by lesbians whose sexuality does not conform to movement standards of purity (primarily lesbian sadomasochists and butch/femme dykes).

These debates were a source of inspiration for Kiss & Tell. In their co-authored 1994 book, Her Tongue on My Theory: Images, Essays and Fantasies, the collective wrote about how the feminist sex wars led to censorship of queer art in Canada and became fodder for their projects. “As lesbian artists… one of the few ways in which we can count on seeing sex images and stories is by making them ourselves…. What we don’t love is how the state censorship denies our rights and threatens our queer culture. Yet this very censorship stimulates us to think of devious and delightful ways to challenge these prohibitions.”

Debates about the ethics of pornography and whether a distinction can be made between pornography and erotica were rekindled through the perspectives of second- and third-wave feminists in North America and beyond. Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line, 1988–90, an exhibition of ninety-eight black-and-white photographs of lesbian sexual practices, sought to ask these questions rather than answer them. In a round-table interview, Lizard Jones said: “Drawing the Line came from a place politically in my community where everything was black and white. They’re all perverts. They’re all censor fascists. And so, we were the ones saying, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute.’ And we were just always that way. There are no simple answers. We were always against the simple answers.”

In Her Tongue on My Theory, Persimmon Blackbridge delved into the often-forgotten role that class plays in defining pornography and erotica. “Historically ‘erotic art’ has meant rich men’s sex pictures and ‘pornography’ has meant poor men’s sex pictures,” she wrote. “The legal defence of artistic merit protects work with high production values and high art aspirations—art that takes more money to produce and is aimed at a well-educated market. It’s a class distinction. The law is set up so we can use our art school diplomas to buy us protection that sex workers have no access to.”

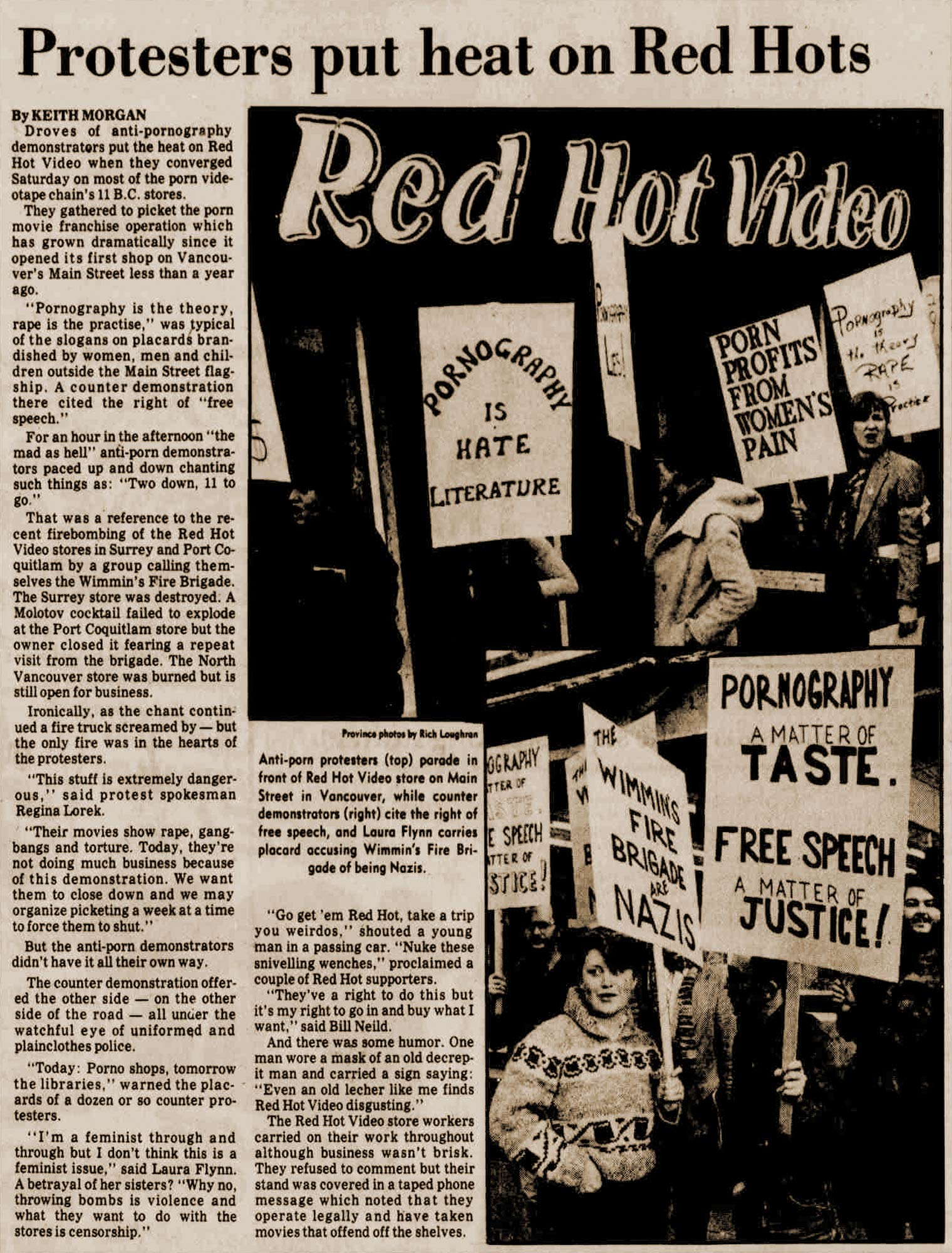

Susan Stewart said of the feminist sex wars, “People had radical passions about this issue, and it was intense.” One result of these debates in Canada was the 1982 firebombing of three Red Hot Video stores that sold soft-core pornography in Greater Vancouver. The anti-pornography group the Wimmin’s Fire Brigade claimed responsibility. The sex wars also led to changes in legislation about obscenity and what kinds of pornography could be censored. The 1992 R. v. Butler court case “concerned the impact of the Charter [of Rights and Freedoms] on the government’s power to criminalize the sale of pornographic materials,” and it changed the definition of obscenity from morals-based to harms-based. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that obscenity laws constitute reasonable restrictions on freedom of expression. The decision meant that pornography that contained explicit sex with physical violence or threats of violence, portrayals of sex with children, and depictions of sex that were degrading or dehumanizing could be censored if the risk of harm was substantial.

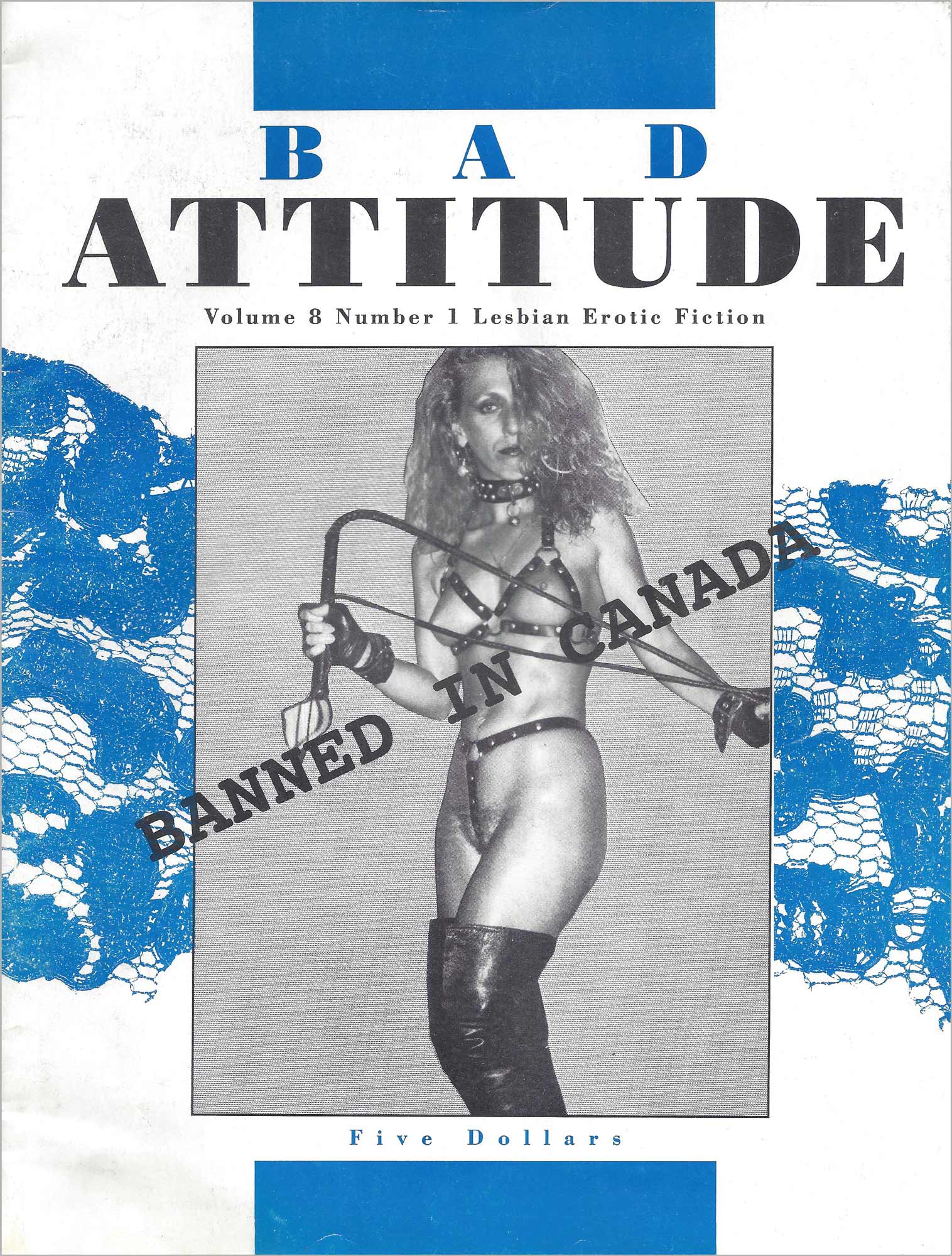

Kiss & Tell was critical of the Butler decision. As Persimmon wrote, “I recognize the good intentions of the women who backed Butler, but it seems the reason it passed with such ease is because it was and is easily co-opted into a right-wing anti-sex, anti-gay, and anti-feminist agenda. Despite some feminist window dressing, it is the same old anti-porn law that’s intended to suppress sexual expression, not sexism.” Many feminists and queer activists thought this ruling would negatively affect lesbian and gay sexual representations, and they were right. Shortly after the ruling, the sexually explicit American lesbian magazine Bad Attitude was seized in a 1990 government raid on Glad Day Bookshop in Toronto. Kiss & Tell’s works were confiscated at the Canadian border the following year.

The feminist sex wars not only impacted the availability of lesbian publications but also dictated what was permissible for lesbian sexuality and sexual practices. S&M, penetration, and the use of dildos (all of which were included in Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line photographs) were controversial territory in some queer women’s circles. Susan commented: “Lesbians were putting such limitations on themselves, in terms of the sex that they could have…. Baby dykes who [saw the Drawing the Line exhibition] were like, ‘Oh, I can use a strap-on. Like, that’s okay?’… Because there was like that whole ridiculous idea that penetration is always violence.”

The practice of S&M (referred to as S/M in the 1980s and 1990s) was particularly frowned upon. It was seen as replicating patriarchal relationships; negatively eroticizing pain, powerlessness, and dominance; and supporting patriarchy, no matter who was engaging in these activities. But for lesbians who engaged in S&M and kink, these sexual practices were liberating and grounded in respect, consent, and negotiation. “In the lesbian community,” Persimmon wrote, “S/M is an area of great conflict, and when we bring it up in our show, the anger and confusion of those debates are right there in the audience.” The federal government took issue with the practice too: two photographs of bondage from the Drawing the Line project were stopped at the Canadian border, and what happened to them is unknown.

The members of Kiss & Tell certainly weren’t the only Canadian LGBTQ2S+ artists to depict S&M lesbian sexual practices during the 1990s. G.B. Jones (b.1965), who is credited with inventing the term “queercore,” created drawings, zines, video art, and films that centred on lesbian sex and kink. Jones’s 1991 Prison Break Out drawings, in which two women seduced, overpowered, and tied up a female guard to escape a cell, and her 1992 Super 8 film The Yo-Yo Gang, about a girl gang that used yo-yos as a form of defence and entertainment, were included in a 1994 exhibition at Mercer Union in Toronto called Girrly Pictures. Lorna Boschman (b.1955) and Kiss & Tell’s video piece True Inversions, 1992, was also part of that exhibition. Like Kiss & Tell, Jones also had work that was stopped at the border after being exhibited in the U.S.

Censorship of Queer Art in Canada

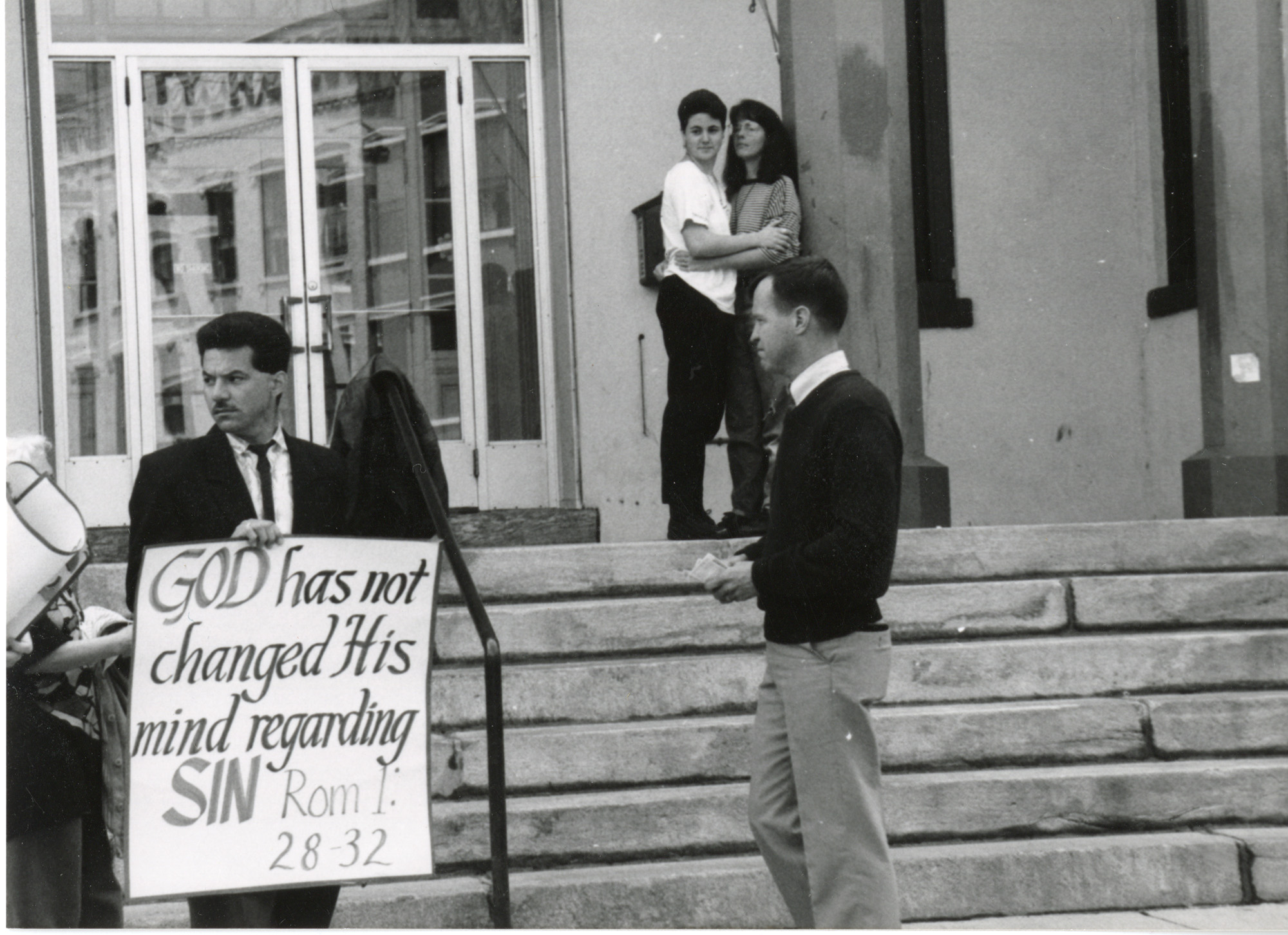

The Drawing the Line travelling exhibition and the True Inversions performance prompted negative reactions that included protests and sage cleanses. The collective was picketed by the Christian right in Washington state and by lesbian separatists in Northampton, Massachusetts. While Kiss & Tell was hanging the exhibition in Northampton, a witch from a lesbian separatist camp smudged Susan and Persimmon, stating that they needed to be cleansed of their supposed violence against women.

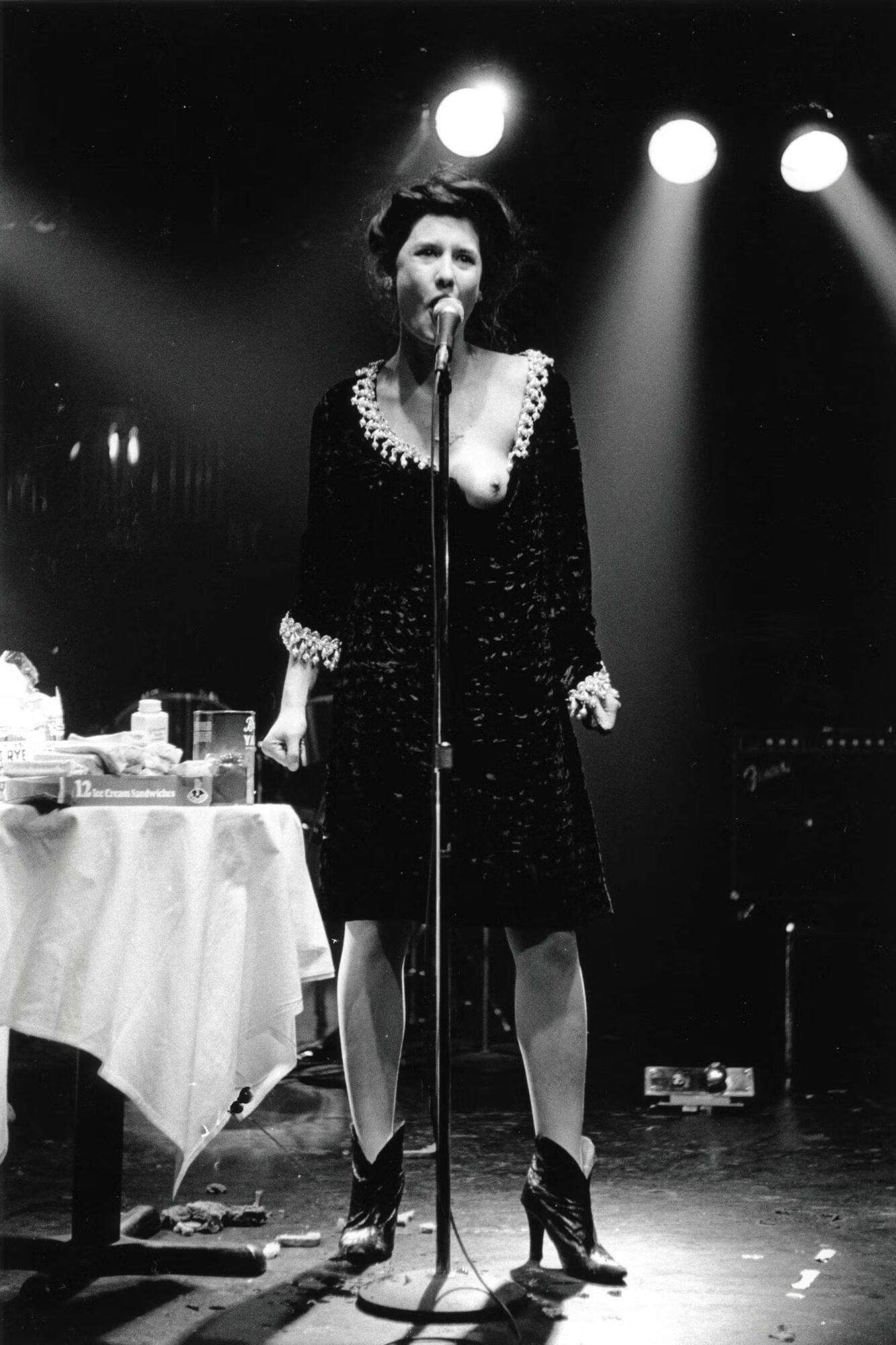

When Kiss & Tell performed True Inversions at the Banff Centre (now Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity) in December 1992, freelance journalist Rick Bell wrote an inflammatory and inaccurate review in the Alberta Report magazine. The headline read: “Kissing and Telling in Balmy Banff: Banff Hosts the Latest in Subsidized ‘Alienation’ and Lesbian Porn.” The article led to public outrage in Alberta and significant media coverage across the country. CBC Radio shows debated “the morals of lesbian sexuality,” and encouraged people to call in to discuss whether gays and lesbians should have rights.

This media maelstrom compelled Ken Kowalski, the deputy premier of Alberta, to denounce the collective. In a press statement, Kowalski called True Inversions “God-awful” and “an abhorrent lesbian show,” and called for “an end to the homosexual shows at government-funded institutions.” Alberta’s labour minister, Stockwell Day, joined the fray by claiming that taxpayer money was being misspent, a commonly used argument to garner public support for the censorship of art and literature. These government representatives, who hadn’t seen the show, were making decisions based on Bell’s review. “Nobody ever phoned anyone in our group to ask whether that review was inaccurate,” said Lizard.

In the U.S., Republican senator Jesse Helms made a similar call to cut government funding to queer artists like Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989), Karen Finley (b.1956), and Andres Serrano (b.1950), whose “depravity… knows no bounds.” Helms’s condemnation of Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic and BDSM photographs prompted the cancellation of a retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1989. In protest, a group of activists projected slides of Mapplethorpe’s photographs on the facade of the gallery. In 1991, a congressional amendment to the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act was passed that prohibited the American National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) from using funds “to promote or disseminate materials that depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual or excretory activities or organs.“ Finley was the named plaintiff along with three other artists (John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller) in a case against the NEA, alleging that the federal agency’s “decency clause” was vague and violated First Amendment rights. The case was ultimately lost in the Supreme Court in 1998.

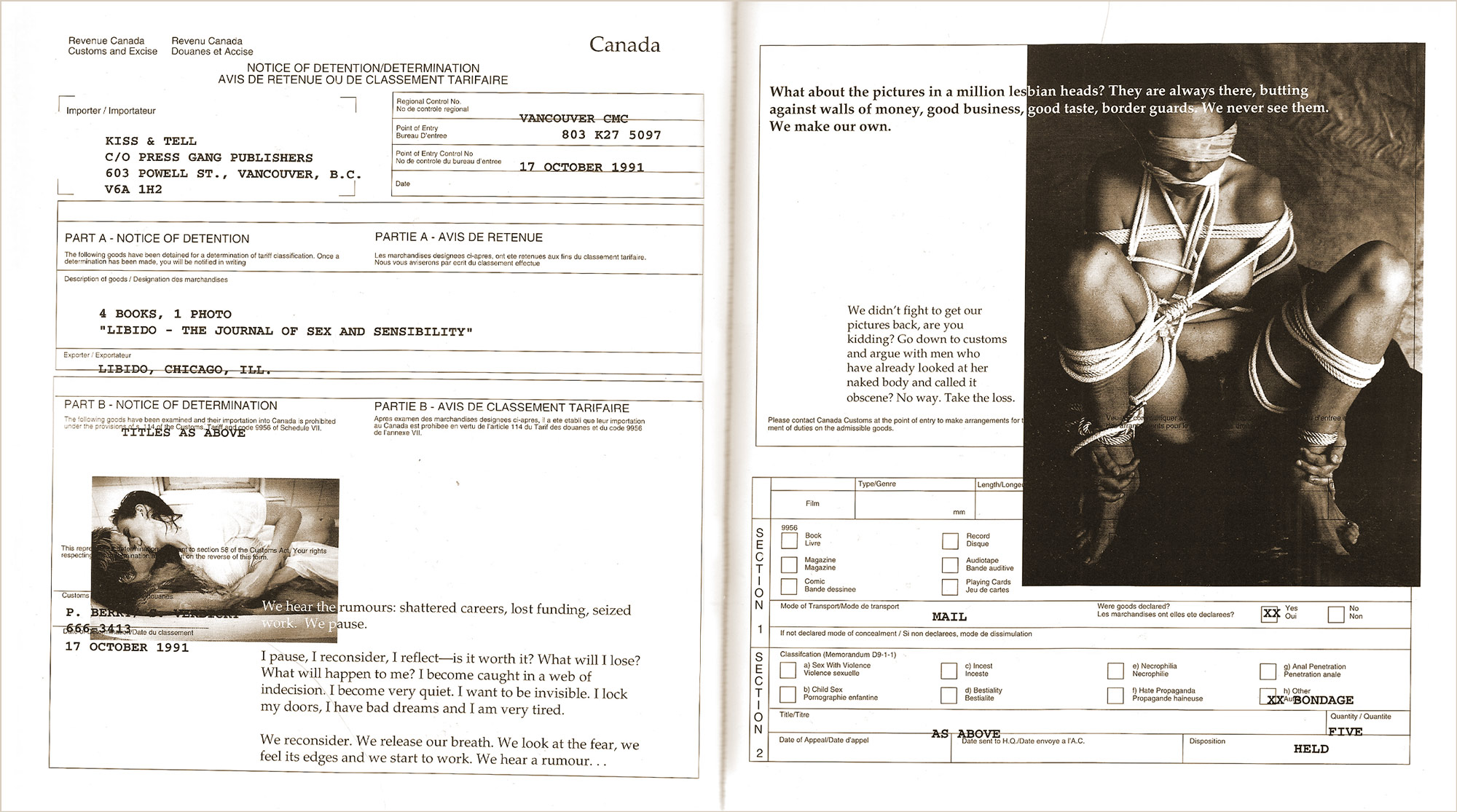

No such funding restrictions based on subject matter were passed by provincial or federal governments in Canada. But Canada Customs did act as censors for queer art and literature entering the country in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1995, when a New York–based publisher sent copies of a G.B. Jones monograph that included S&M images to Canada, customs “designated them as ‘immoral’ and prohibited their importation, citing their depiction of ‘bondage.’” The copies were confiscated and later burned. Despite being exhibited in several Canadian galleries, photographs from Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line exhibition were stopped at the Canadian border on four separate occasions, as were magazines with articles about the exhibition.

In 1991, the U.S. magazine Libido, which included a feature article on the exhibition with photos, was one of those detained at the border. The photographs sent to Libido for layout were seized when they returned to Canada. An issue of the lesbian magazine Deneuve with a review and photos from Drawing the Line was stopped on its way to Little Sister’s, a queer bookstore in Vancouver. Copies of Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line postcard book, published in Canada and distributed by Inland in the U.S., were seized en route to Edmonton from the States.

In their performance Borderline Disorderly, 1999, Kiss & Tell discussed why they didn’t retrieve their work from border agents. Susan said, “No way I will go to get my photos…. I would have to say that I made them,… that I’m the evil pornographer whose work they have deemed fit to seize.” Persimmon chimed in, “Down at customs, context doesn’t count. There’s a checklist. Bondage? Bingo!… Walk into a room where the context is set by a bunch of guys in suits with a checklist and their fingers on our photos? Nah, let the pictures go.”

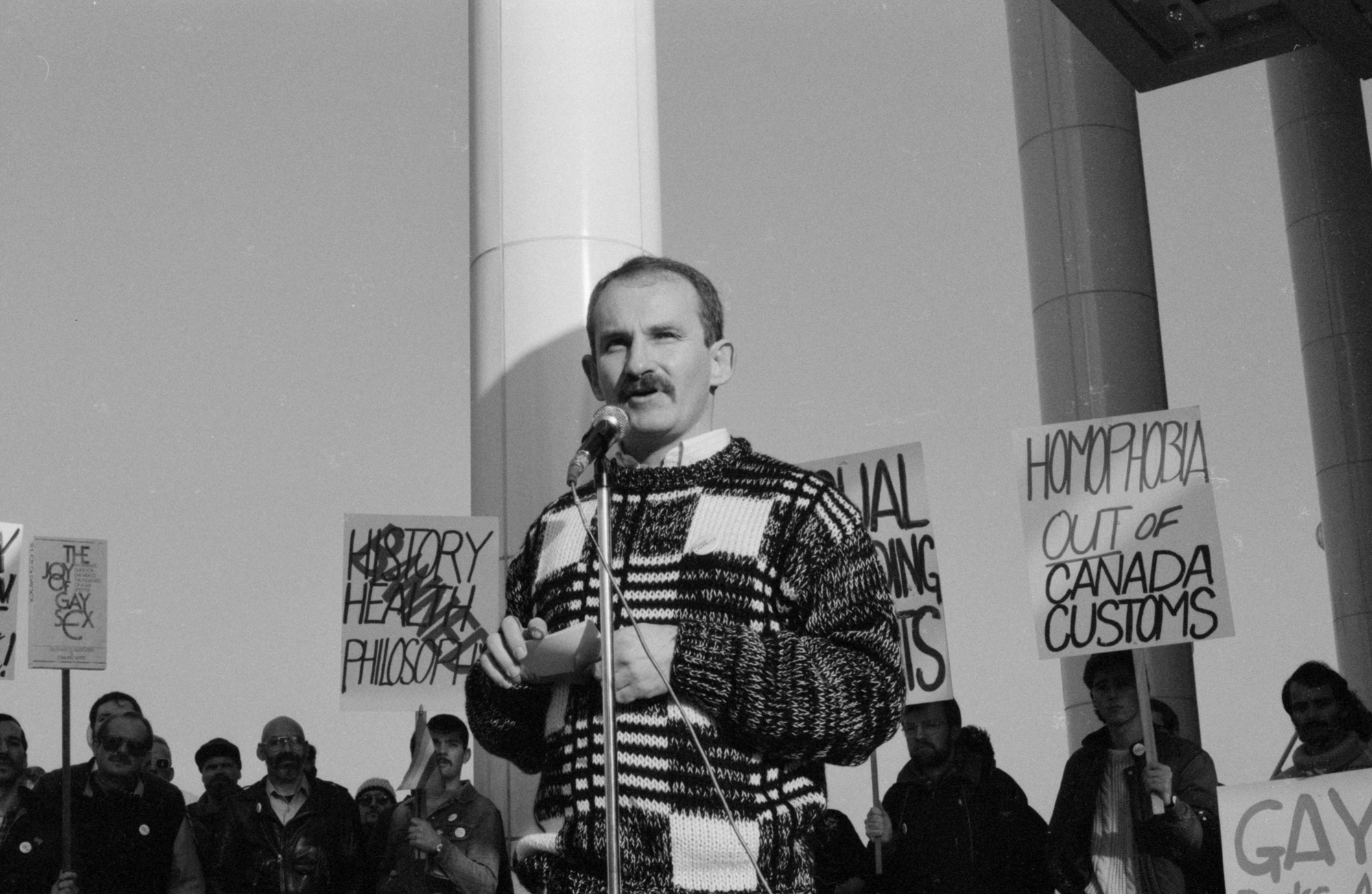

The backlash against queer art in Canada wasn’t centred solely on artworks and performances. Canada Customs flagged queer publications far more frequently than other types of literature and tended to target shipments to gay and lesbian bookstores. In 1994, fed up with the frequent confiscation and destruction of their orders, Little Sister’s launched a lawsuit against the federal government over its customs policies. Joe Arvay, the lawyer for Little Sister’s, argued that queer publications and artworks were being unduly targeted by customs, and that “gay and lesbian pornography is sufficiently different and complex from mainstream pornography” and thus the government should “allow entry into Canada of all books and magazines respecting gay and lesbian issues or relationships and intended for a gay and lesbian readership.”

To help fund legal costs, the bookstore, in collaboration with the American publisher Cleis Press, put out Forbidden Passages: Writings Banned in Canada. The 1995 book featured excerpts from works that had been identified as sexually “degrading,” “obscene,” or “politically suspect” by Canada Customs, including writings by bell hooks, Jane Rule, Dorothy Allison, Susie Bright, and Joseph Beam, artworks by Tom of Finland and David Wojnarowicz, and comics by Diane DiMassa. A short review about Kiss & Tell by Diane Anderson, originally published in the issue of Deneuve seized at the Canadian border, was also featured. Anderson writes:

At a time when censorship issues are on many women’s minds, Drawing the Line is particularly important because it asks viewers to make choices and form opinions about sexual imagery—lesbian sexual imagery—that could have an effect on even the dominant culture audience…. Bringing images like fist-fucking and dildo play to the gallery wall… will merely bring them into the light so they can be discussed with free inquiry.

As the first witness in the Little Sister’s court case, Persimmon spoke about the complexities of lesbian sexual imagery: “Sometimes, as women, we are acknowledged only as victims, or only self-affirming subjects. Neither position reflects our actual lives. Our sexuality is far more complex. We respond to sexual images in very individual and sometimes conflicted ways.” Feminist law scholar Ann Scales, another witness, argued that lesbian depictions of S&M differ from heterosexual pornography because it is often the participants themselves who create the images, and they are the ones who set the consensual boundaries for what will and won’t happen. Scales’s description of lesbian S&M imagery was in keeping with how Kiss & Tell created their own photographs of kink sexual practices.

The B.C. Supreme Court judge found that customs agents had unduly targeted shipments from Little Sister’s, and that this violated section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protects freedom of expression. However, he ruled that this violation was justified under section 1, which states that these rights and freedoms are subject to reasonable limits prescribed by law. Thus, the Butler decision overrode the right to freedom of expression. In 2000, the case was taken to the Supreme Court of Canada, where the ruling was upheld as not violating section 2. However, it ruled that the implementation of the law by Canada Customs officials was discriminatory and should be remedied. The Supreme Court struck down part of the law that required an importer to prove material was not obscene. Instead, the onus was on the government to prove the obscenity of seized materials. The ruling upheld Canada Customs’ right to prevent materials already banned as obscene by the courts to enter Canada, but they could no longer pre-emptively detain material that had not been already adjudicated. Little Sister’s had won its legal case against Canada Customs.

Despite repeated seizures by Canada Customs, Kiss & Tell refused to be intimidated. As part of her testimony in the case, Persimmon said: “We’ll continue to explore sexual representations…. We will continue to show our art internationally despite the fear of losing our work.”

Queering Photography

Photography played a critical role in Kiss & Tell’s oeuvre. Drawing the Line, 1988–90, queered photography through its lesbian subject matter and a collaborative process that didn’t centre the photographer as the sole artist. As Persimmon wrote in Her Tongue on My Theory: “On our first Drawing the Line shoot we all took turns behind the camera, but since Susan’s been a photographer for 20 years, it was no big surprise that her photographs were way more skillful. Lizard and I were more excited about taking on the challenges of modelling…. So on the shoots and in the darkroom, we had our individual roles, while the concept, decision making, and ongoing ideas happened among all of us.” The collective’s purposeful collaboration challenged the notion of individual creative genius (usually reserved for white, male, and heterosexual artists) that is so often at the heart of art historical discourses.

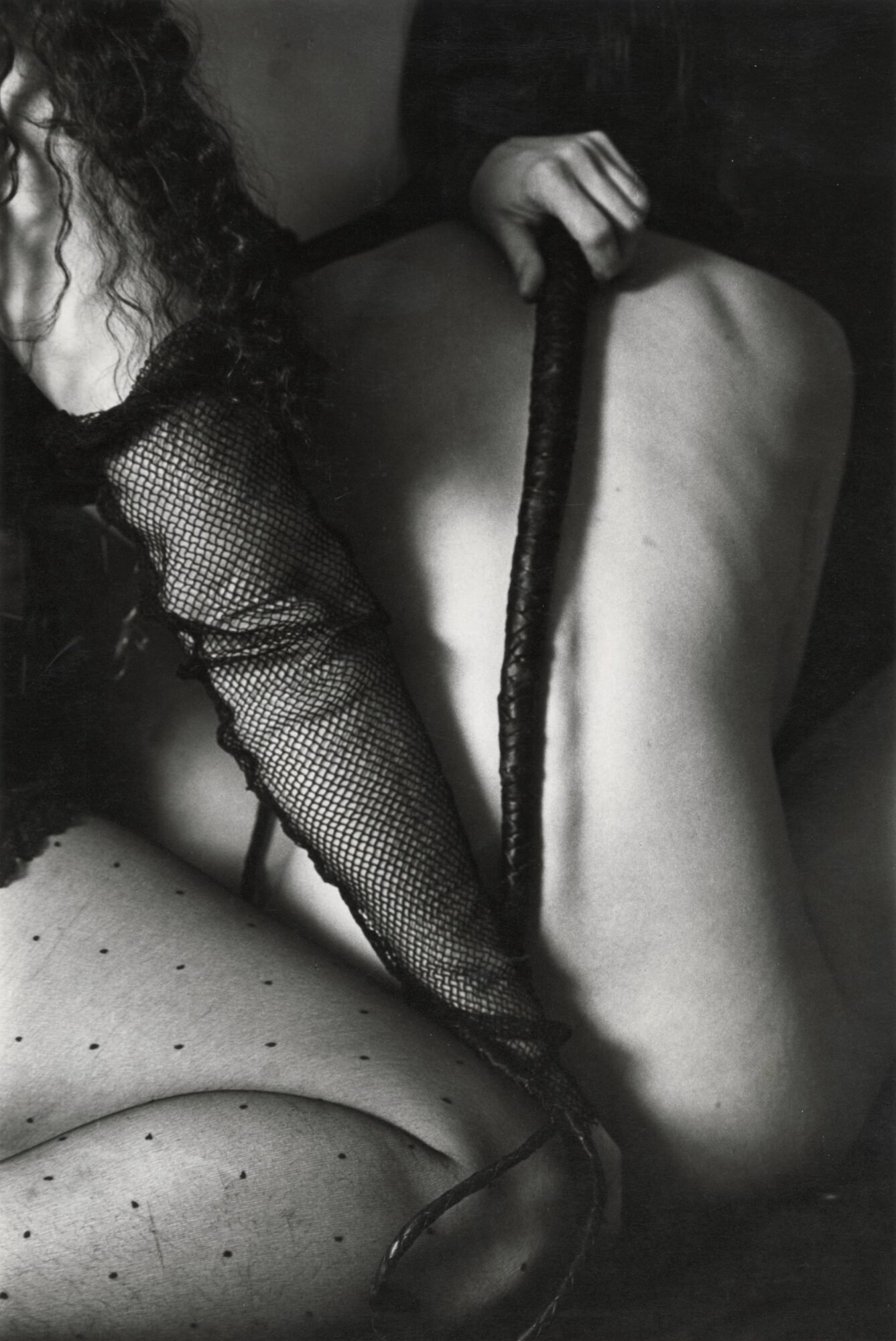

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90, photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm, Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby.

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90, photographic print, 35.5 x 27.9 cm, Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby.

The deliberate nature of Kiss & Tell’s creative process in Drawing the Line extended to their artistic intention. They were photographing collaborative experiences between lesbians engaged in highlighting safe, sane, and consensual sexual practices that included S&M and kink. This part of the equation can be easily forgotten by viewers having a gut reaction to artworks, as was the case for some with two bondage images of Lizard tied up with white rope, her eyes wrapped with a white silk blindfold, her knees bent, and hands tied to her ankles. One woman wrote on the wall below one of these images: “I find this alarming. It evokes for me images of women who are subjected to this against their will.” The Canadian government agreed—these photos were seized by Canada Customs. In their 1999 Borderline Disorderly performance, Lizard joked that Persimmon must have gotten a knot-making badge as a Girl Scout, given how good she was at tying her up for the photos. One woman who saw Drawing the Line echoed this sentiment, writing on the wall: “Girl Guides was good for something.”

In the letter Persimmon read to her mother in 1992’s True Inversions performance, she discussed the importance of photographing queer bodies:

You know my naked lesbian body is available in bookstores across the continent. On display in galleries, discussed in newspapers…. In your world, one doesn’t kiss in public. It’s cheap, you would say, but I kiss in public. I fuck for the camera…. I fuck this woman who’s not even my lover, for the camera, making art. In your world, it’s unthinkable…. Lizard [says], “We are people who will risk being killed in order to fuck each other.” We queers, she means. She means there are people who want us dead. You know this is true, but you forget at times. We never forget.

Kiss & Tell’s stories and photographs about lesbian lives were a form of radical and defiant activism in the face of censorship, homophobia, repression, and threats of violence. In the 1990s, lesbians, bisexual women, and gender non-conforming people were generally invisible in art and photography. Photographers and artists fought back against this invisibility by bringing representations of lesbian subjectivities into the public sphere.

One such photographer, the American Catherine Opie (b.1961), represented queer lives through photographs of queer women and men in her Portraits series, 1993–97, and of lesbians in her Domestic series, 1995–98. Both were grounded in the documentary style of portrait photography but shone a light on subjects usually absent from that format. The Portraits series depicted queer S&M communities, while the Domestic series focused on lesbian couples and families at home. Opie’s work featured a diversity of age, race, class, and location to show the range of family structures that exist beyond the heterosexual paradigm.

-

Catherine Opie, Gina & April, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1998

Pigment print, 101.6 x 127 cm (print), 104.1 x 129.5 x 5.1 cm (framed)

-

Laura Aguilar, Clothed/Unclothed #30, 1994

Two gelatin silver prints, 50.8 x 40.6 cm (each)

Collection of Cheri Gaulke and Sue Maberry

Another American artist, Laura Aguilar (1959–2018), was at the vanguard of lesbian photographic portraiture. She created a series of black-and-white photographic portraits titled Latina Lesbians, 1986–90, that included the subjects’ words in their own handwriting. For one portrait, the sitter, Carla, wrote: “I used to worry about being different. Now I realize my differences are my strength.” By including the subjects’ words in the photographs, Aguilar queered the genre by depicting the sitters as individuals rather than mere objects to be admired. In another black-and-white series, titled Clothed/Unclothed, 1990–94, Aguilar shows her lesbian sitters against a traditional black studio backdrop. We see them in two views: with and without clothes. According to Susan, who spent time with the artist, Aguilar was a strong supporter of Kiss & Tell.

Like Aguilar’s work, Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line photographs were shot in black and white, which tied them to pre-1980 art photography. The format also referenced the black-and-white thinking of the feminist sex wars, and what better way to explore it than with grey tones? In Her Tongue on My Theory, Susan wrote: “Photographs have the wonderful ability to traverse the edge between what is commonly known as reality and the invented, making it unclear which is which.”

Unlike Opie and Aguilar, Kiss & Tell blurred the boundaries between documentary and art photography by creating staged photographs that depicted actual sex acts. The project employed various locations, sexual practices, camera angles, compositions, and lighting to make two models appear to be multiple women. With analogue photography, there’s an assumption that the photograph is providing factual insight into a particular event, era, or person. The Drawing the Line photographs were also significantly different from Opie’s and Aguilar’s works because the collective’s photographs did not document women who were lovers in real life. Rather, the subjects in Kiss & Tell’s project were models having sex for the camera. Director Lorna Boschman questioned what “real” sex entails in Kiss and Tell’s True Inversions video: “Is it real sex if you have to stop and start when the director tells you to?”

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90, photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm, Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby.

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90, photographic print, 35.5 x 27.9 cm, Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby.

Drawing the Line also queered the act of viewing by providing spaces—the walls of the exhibition spaces, the men’s comment books, the postcards—to respond directly to the photographs. The international exhibitions established a community of queer viewers and a place for queer women to voice what they thought of the lesbian sexual practices being represented. Kiss & Tell was battling against the invisibility of lesbians in contemporary culture, while also pushing back against a silencing of sexualities that stemmed from restrictive upbringings and the supposed protection granted by staying in the closet. Allowing women to comment anonymously provided a space for lesbians to share their perceptions and attitudes about sex without fear. For many of these women, it was their first time seeing photographs of lesbian sex created by lesbians.

Viewing the copious slide sheets at the Kiss & Tell archive at Simon Fraser University Library Special Collections and Rare Books in Burnaby, I was struck by the incredible amount of queer imagery they created. The hundreds of photographs in these sheets demonstrate the imagination, play, courage, camaraderie, and experimentation needed to create the work. They read like an archive of queer sexual practices, a behind-the-scenes account of lesbian image production. In some photographs, Lizard and Persimmon break into laughter. In others, they kiss passionately. They touch each other’s breasts and genitals. They enact power play scenes. They play with each other in the shower and the bath and so much more. The respect, trust, and care between the models and the photographer are palpable. A very rare catalogue of lesbian aesthetics and desire emerges from these slide sheets and in the final exhibition of Drawing the Line.

Humour in Queer Performance

Humour has often been used as a survival strategy by marginalized and oppressed peoples. For their part, Kiss & Tell employed humour and comedy to provide catharsis and foster understanding. Funny stories and comedic deliveries offered a relatively safe entry point into subjects that might otherwise be difficult for audiences. In a round-table interview, Lizard quoted Lorna Boschman as saying: “If you’re going to be sexual and make people really uncomfortable, and they’re aroused and they don’t know what to do, you got to give them some way to laugh because they won’t know what to do.” Susan concurred. “You know, it gave a release for people. We gave that opening to laugh because we had a lot of other complicated things that we were introducing.”

Moving from potentially uncomfortable topics to more humorous, light ones was a release valve for viewers’ potential discomfort. In their 1992 True Inversions performance, Persimmon told a fictional story in which she slapped her girlfriend as a part of a sexual encounter. This section of the performance tended to make audiences particularly uncomfortable—they often reacted with an audible gasp, and some people even walked out. Persimmon followed up in an aggressive tone, “I slap her again just to make sure.” The audience’s attention was then pulled away by Lizard, who launched into a melodic monologue about an unrequited crush on a co-worker: “Part of me knows that she feels this thing.” The transition from a story about rough sex to one of gently lusting after a co-worker was jarring and humorous, and the audience did laugh (out of discomfort or because Lizard’s comedic delivery was spot on, we’ll never know).

A similar comedic transition occurred in That Long Distance Feeling: Perverts, Politics & Prozac, 1997, when Persimmon discussed going to see a new psychiatrist for depression. “I’m at the corner going over my ‘talk to the new shrink’ script in my mind and then recklessly out loud: ‘The laws of sanity are so flimsy once you get down to it, so easy to cross over.’ I shouted for a whole block, scaring lawyers.” Lizard humorously chipped in, “People get punished for scaring lawyers.”

The collective’s commitment to humour as an accessible entry point is shared by the Canadian art duo Shawna Dempsey (b.1963) and Lorri Millan (b.1965). In 1997, they founded Lesbian National Parks and Services “to insert a lesbian presence into the landscape.” Dressed as park rangers, the pair assisted tourists in Alberta’s Banff National Park, handing out brochures about fictional lesbian flora and fauna and highlighting imaginary institutions such as the Invisible Plaque Dedicated to Our Founding Foremothers. Like Kiss & Tell, Dempsey and Millan brought lesbian subjectivities into typically heteronormative public spaces. In one interview, Dempsey and Millan recounted a typical encounter with a middle-aged, white Canadian man:

When he got up to us, he read the label of my shirt insignia out loud: “LESBIAN National Parks and Services.” Realizing he didn’t know (or couldn’t acknowledge) what he was dealing with, he suddenly had to improvise. His conclusion—“Now that must be Federal, isn’t it!”… When Dempsey responded (herself improvising) “Well no, actually we’re international,” the man remained steadfastly puzzled. Millan continues, “by the time we parted I still don’t think the penny had dropped for him. Perhaps then he thought ‘lesbian’ was one of those supposedly obscure central European countries.”

While Dempsey and Millan gave a few lucky park visitors T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “Eager Beaver,” Kiss & Tell used inside jokes to bond with queer audience members. In their performance Corpus Fugit, 2002, Lizard talked about the pain of breakups while nodding to the stereotype that lesbians play softball: “I really loved her. I laid my heart at her feet and then she stepped on it, wearing baseball shoes with spikes on them. Hundreds of punctures all over my heart.”

Kiss & Tell extended grace to their audiences through comical moments and laughter, but humour was also central to their creative process. In an interview with the group, Persimmon talked about how many viewers assumed that the process of creating the bondage photographs in Drawing the Line, 1988–90, was uncomfortable. “[Susan and I] did a workshop with a bunch of people who were convinced that that was true. And we did this whole bondage thing with me with these tiny, tight black strings. And it was really disturbing looking. They got to see how [it was done]. How we cracked up laughing all the time and there was really no problem.”

Disability Art & Activism

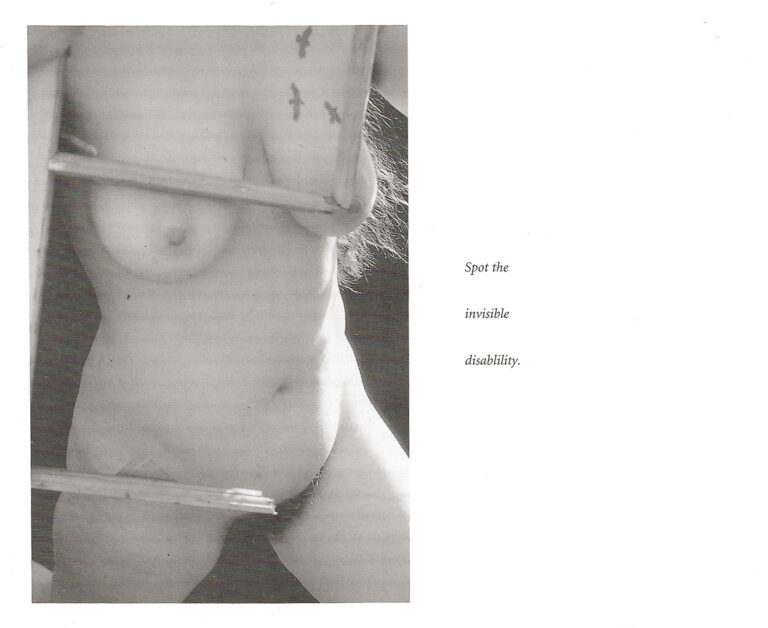

In Kiss & Tell’s co-authored 1994 book, Her Tongue on My Theory, a photograph of a broken wooden window frame rests against a white woman’s naked body viewed from chest to mid-thigh. The caption beside the black-and-white photograph reads: “Spot the invisible disability.” I recognize this body as Persimmon’s by the tattooed birds circling above her left breast, and I know the answer: learning disabilities, self-harm, mental health issues, and depression. But the average reader would not know these details, and they would wonder.

Persimmon and Lizard brought to light how their disabilities affected their lives and other people’s perceptions of them. In Kiss & Tell’s performance That Long Distance Feeling: Perverts, Politics & Prozac, 1997, Lizard revealed:

When you have multiple sclerosis, you have really low energy and you get depressed…. In 1997, avoiding Prozac is an uphill battle…. MS [multiple sclerosis] and sex, it’s a problem…. If I start taking Prozac like they say, I’ll be perkier and less fatigued, and the sex will just come rushing back. Forgetting of course that twenty percent of people who take Prozac lose their sex drive completely…. I guess the message is sex is for people who are already cheerful and physically fit, and the rest of us should just take our pills and go to bed alone.

Both Persimmon and Lizard are long-time disability activists. From 2013 to 2016, Lizard was the artistic director of Kickstart Disability Arts & Culture, a Vancouver non-profit. In an interview, she discussed the similarities between queer people and those with disabilities: “On the one hand, people [with disabilities] want to be recognized as normal. And on the other hand, we’re not, and we don’t want to be. We have different things to say, and we have a different experience. Disability art is part of the revolt against normalization, while others believe that their disability does not define them.”

In 1997, Lizard wrote Two Ends of Sleep, a novel in which a lesbian named Rusty navigates her MS diagnosis and the increased amounts of sleep she now requires. The lines between fantasy and reality blur, like the space between waking and sleeping. Did she cheat on her girlfriend or was that just a series of erotic dreams? Like many of the stories in Kiss & Tell’s performances, Two Ends of Sleep is humorous, heartbreaking, and sexy.

For her part, Persimmon has been creating works about disability, especially around mental health, since the 1970s. In 1996, she published Sunnybrook: A True Story with Lies, a book about working as a counsellor for people with intellectual disabilities at the Woodlands School in New Westminster. Five years later, she collaborated on the exhibition From Inside/Out with twenty-eight former inmates at B.C. institutions for people with intellectual disabilities—including Woodlands, the source of hundreds of reported cases of physical, verbal, and sexual abuse. The exhibition drew increased attention to what had happened at Woodlands and helped nine hundred former residents gain reparations.

Persimmon’s novel Prozac Highway (1997) also included autobiographical elements. The protagonist, Jam, was an “an over-forty cleaning lady and lesbian performance artist,” struggling to pay for food and her meds. She talked about the difficulties of being a performance artist: “Maybe they [the bookstore venue] hadn’t known how to pull in an audience for a couple of queers, and we’d be performing to an empty room. Or to an audience of curious hets who wouldn’t understand the sex or know when it was okay to laugh. Or to a room full of anti-porn dykes ready to hate us.”

In an interview, Persimmon discussed how the medical system failed to diagnose her properly:

I was dealing with depression, which actually had a physical cause, but since I was a known nutcase, it never got diagnosed. It was just like, “Oh, look at you. You’re the crazy person. And now you’re crazy in a whole new way that you’ve never been crazy in before. But why investigate?” I was depressed and I did not know how to deal with depression…. So then, [many years later,] my depression was cured by parathyroid surgery. Ding. It’s gone. But I was left with kidney failure which could have been avoided if I had been diagnosed earlier.

This frustration with doctors is discussed in That Long Distance Feeling. Grievances include how doctors assume patients are heterosexual and butch women aren’t biological mothers, how they simplify disability, and how they claim problems can be solved simply with a pill. During their time in Kiss & Tell, Lizard and Persimmon were in a writing group of two, encouraging and helping each other in their writing, art, and activism. In Kiss & Tell’s performances and book of essays, and in their individual writings and artworks, Persimmon and Lizard brought, and continue to bring, much needed recognition and understanding of disability issues and ableism.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements