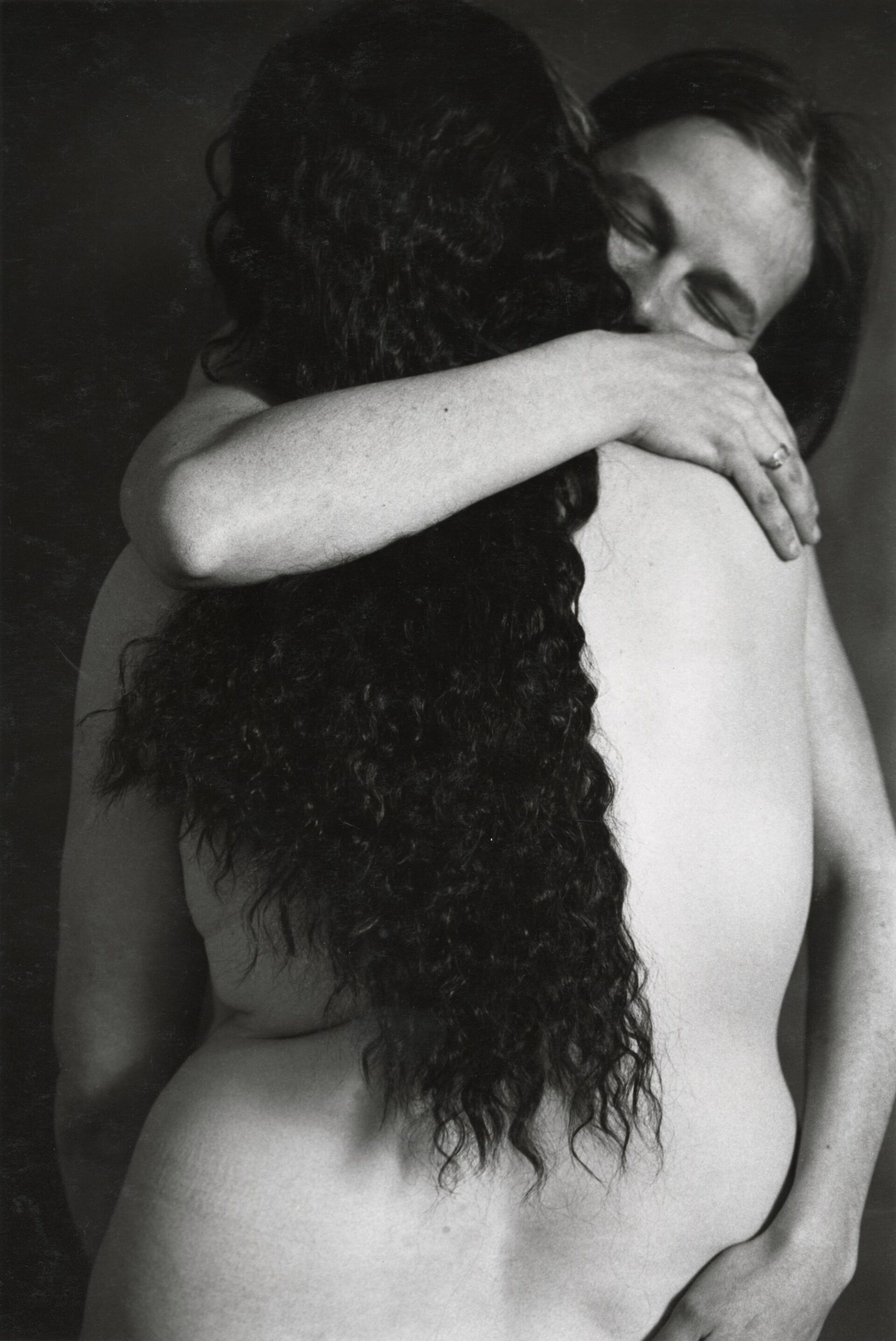

Drawing the Line 1988–90

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 35.5 x 27.9 cm

Simon Fraser University Library Special Collections and Rare Books, Burnaby

Kiss & Tell’s first and most well-known work, Drawing the Line, earned them accolades and citations, including from the Oxford Dictionary of Art, which declared that the project “best embodies the spirit of gay and lesbian art.” In this work, Kiss & Tell depicts the female nude photographically, giving the models as much agency as the photographer and representing a range of lesbian sex acts. This photograph of two women hugging is the only stand-alone piece in the exhibition. One woman is naked, her long black hair contrasting with the white skin of her back and arms. The other holds her, and only the top half of her face is visible. This image was purposefully chosen to kick off the exhibition because of its relative tameness. However, one of the women is touching her partner’s naked bottom (cropped by the edge of the frame), a foreshadowing of the more sexually explicit photographs to come. One reviewer commented that the exhibition “feeds a craving for imagery by a community alternately written out of history or misrepresented by commercial straight porn.”

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, Drawing the Line, 1988–90

Photographic print, 27.9 x 35.5 cm

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

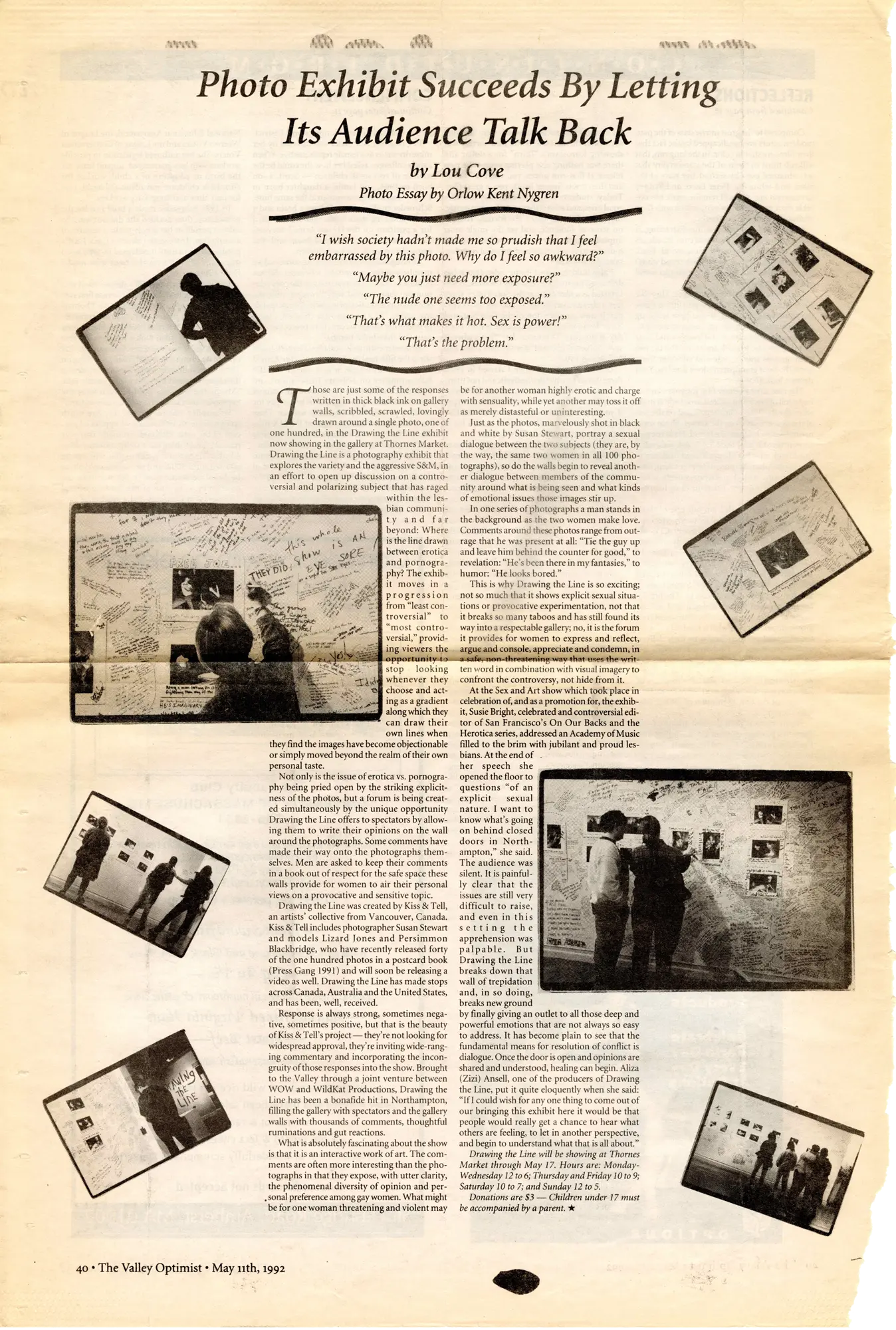

In creating their inaugural work, the collective drew inspiration from the debates between the pro-sex and anti-pornography camps during the feminist sex wars of the 1980s, as well as discussions within Vancouver’s lesbian community around what was considered permissible in representations of lesbians. Over three years, Kiss & Tell photographed lesbian sexual practices ranging from kissing—clothes on, clothes off, clothes torn away, and completely naked—to fisting, threesomes, BDSM, and voyeurism. As they explained in their artists’ statement, “We all agreed that to do the series right we had to be willing to do things we’d never do in our lives. And to try to make it look real. There was a lot of nervous giggling.” First shown at the Women in Focus Gallery in Vancouver in 1988, Drawing the Line grew in reputation as it travelled to fifteen cities in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and the United States.

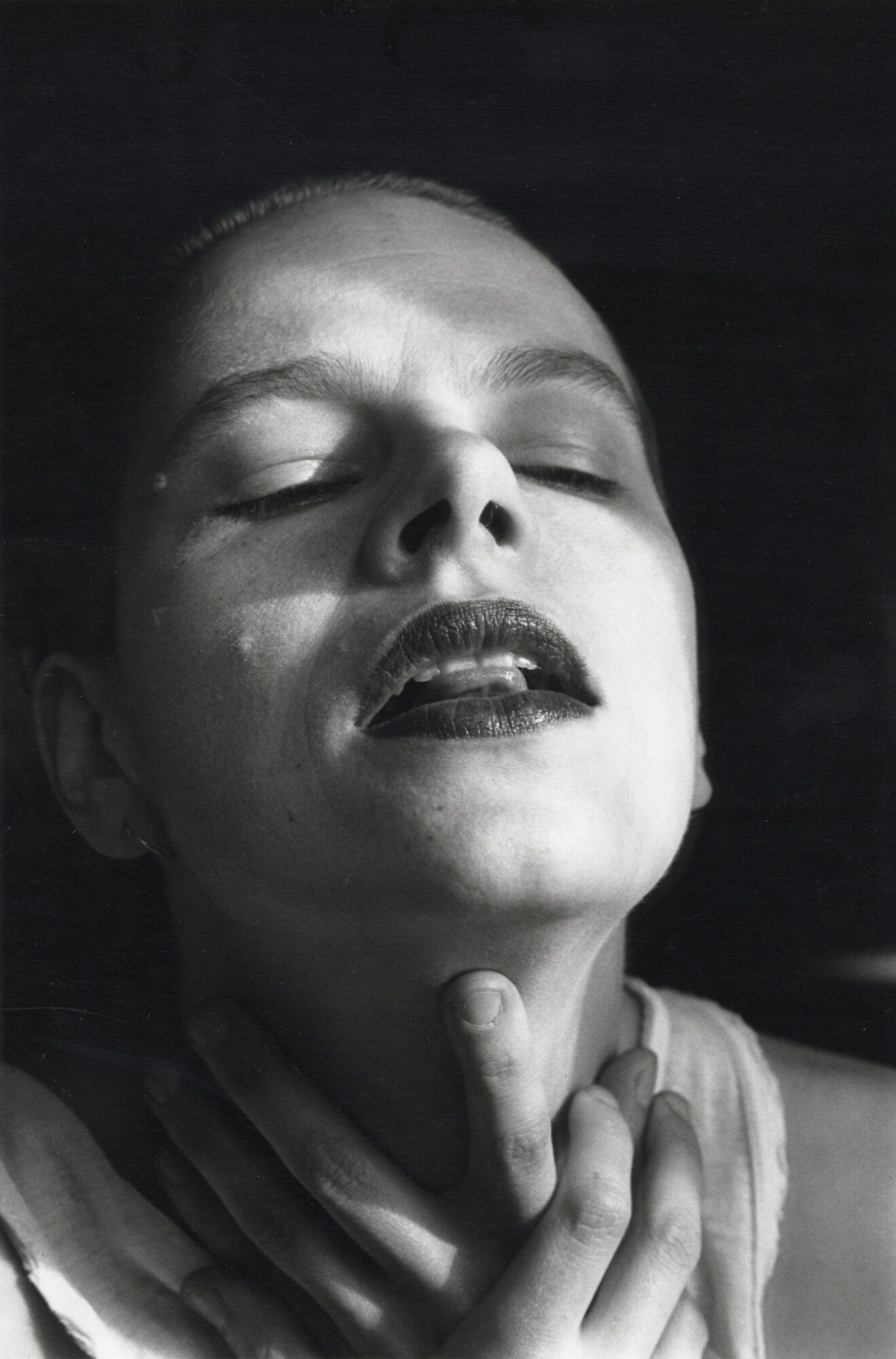

In the spirit of collaboration, the members of Kiss & Tell began by taking photos of each other but soon settled on Susan Stewart, who was the expert in the medium, as the project’s photographer. Persimmon Blackbridge and Lizard Jones became the models. In most of the photographs, their faces are seen in profile, from behind, partially obscured, or cut off by the frame. The poses and camera angles suggest that these could be any white women, any lesbians. With this project, Kiss & Tell explored the grey areas between the black-and-white positions taken in the feminist sex wars and were determined to see where viewers would draw the line when looking at a continuum of lesbian sexual practices produced by lesbians.

Hung in groups of two to four, the unframed black-and-white photographs in the exhibition were meant to be read linearly, from what could be considered least contentious to most controversial. The models were photographed in diverse locations, including a bathtub, parking garage, public washroom, rooftop, woodworking shop, warehouse, and forest, and they engaged in a variety of sex acts. The images most often viewed as controversial involved S&M practices: bondage with rope, submission, domination, wax play, power play, nipple clamps, leather, whips, aggressive grabbing, and being chained up.

The exhibition was a pointed response to lesbian erasure, to the creation of lesbian sexual imagery by men for the male gaze, and to lesbian activists who believed queer women shouldn’t portray themselves as sexual beings. As Canadian writer and cultural critic Jean Bobby Noble wrote in an exhibition catalogue for Drawing the Line, these activists wanted “to desexualize lesbianism to make it more acceptable to both feminism and mainstream heterosexual culture, and to challenge clinical definitions of lesbianism as sexual deviancy.”

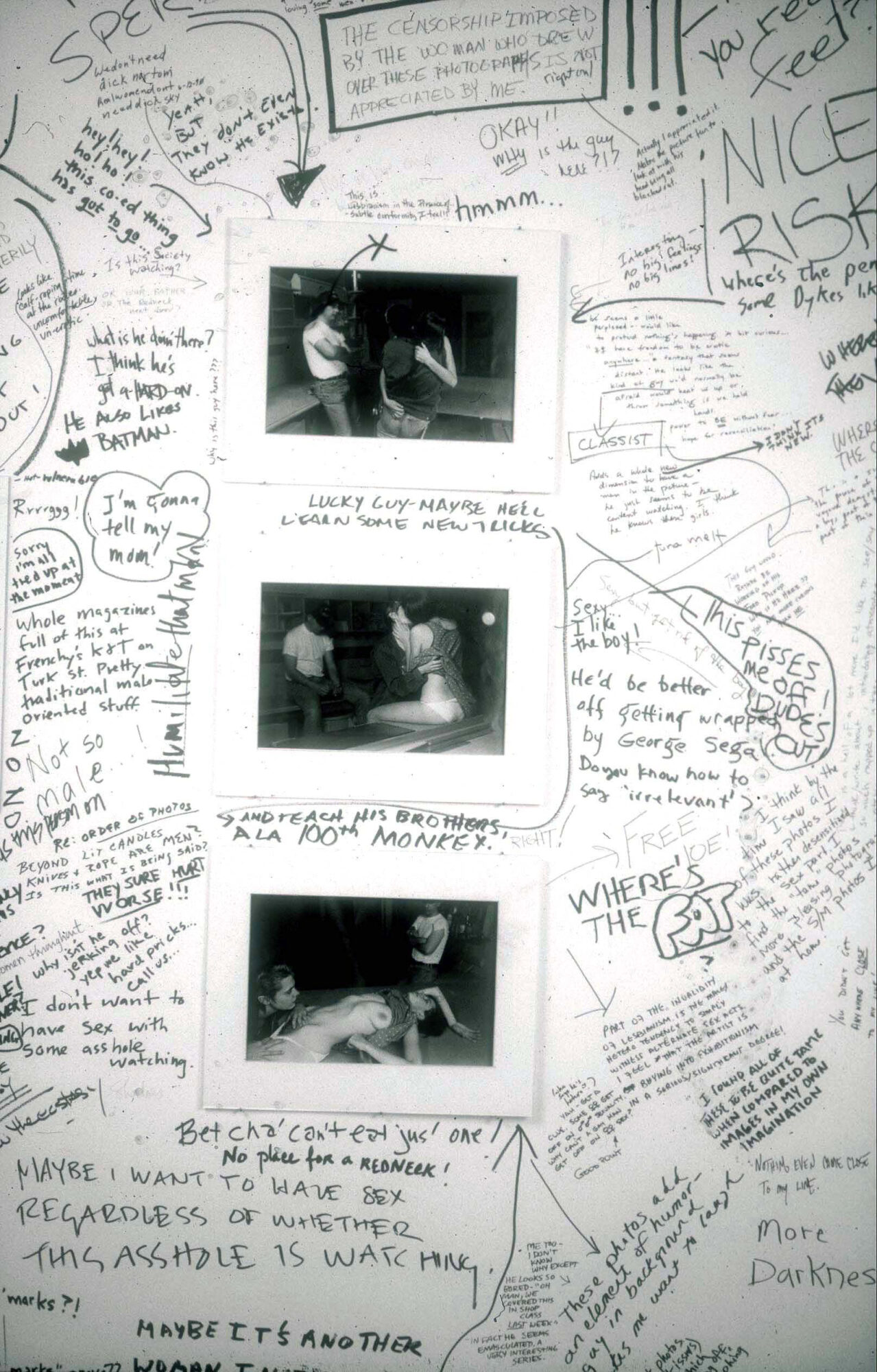

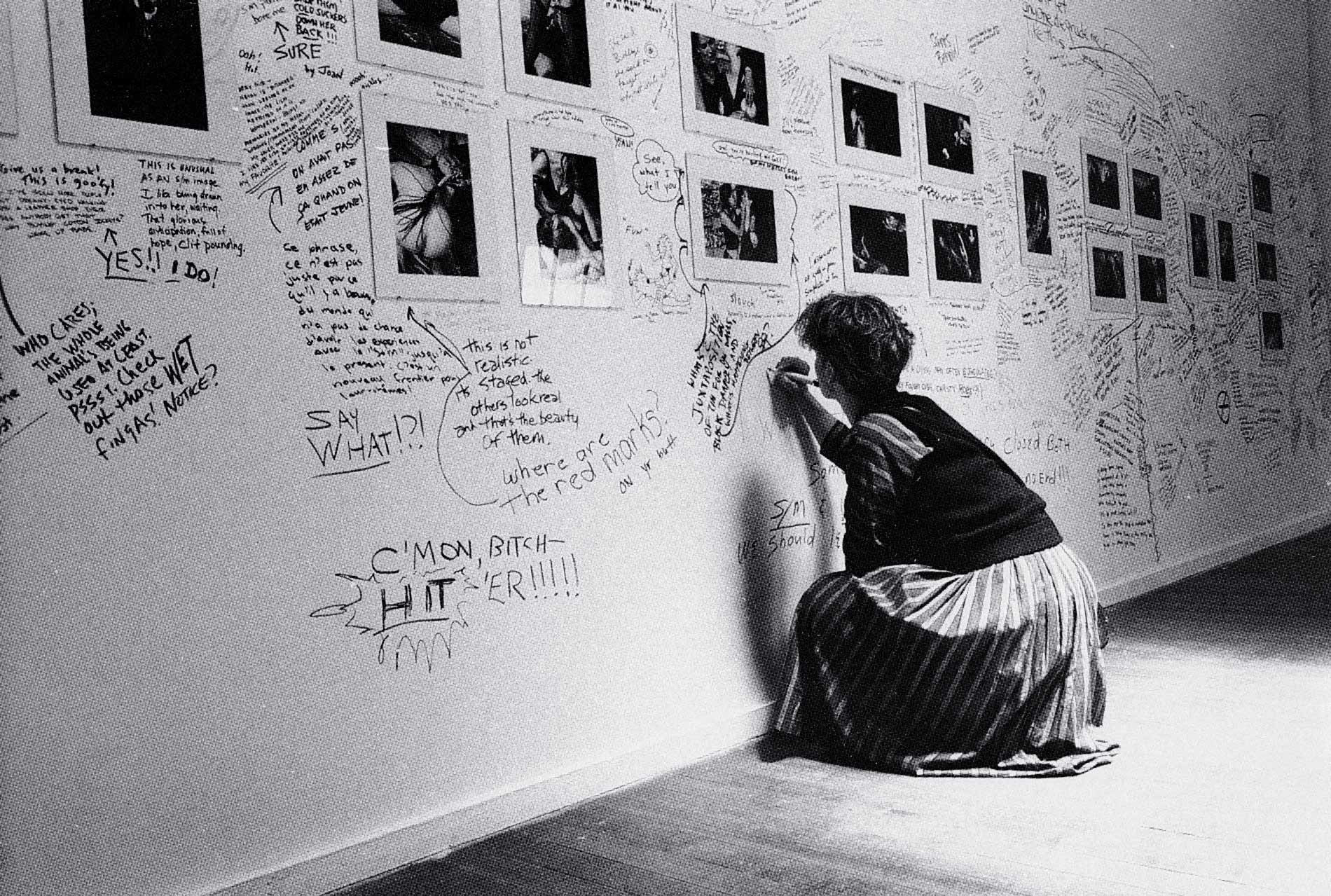

Kiss & Tell broke with tradition in their approach to viewer interaction in a gallery context. When viewing Drawing the Line, women could write comments on the walls with black markers, and some even scrawled on the photographs themselves. Male viewers, however, could write only in a book located at the end of the show. At the time, sexual imagery was discussed in a way that echoed the gender binary, where women’s voices were silenced or secondary. Separating men’s comments was a strategy to centre women. As documentation of the exhibition shows, the walls became covered with comments from viewers responding to one another. This kind of exchange is now common in the age of social media, but it was groundbreaking in the early 1990s. Persimmon noted: “The pictures float in a sea of text, no longer functioning as separated as sexual images, but literally within the context of debates, discussions, and disagreements about sexual representations.”

The final photographs in the exhibition were a grouping of three images of a man watching two women kiss and touch each other. These photographs most closely approximated sexual representations of lesbians within mainstream porn created by men for men. But Kiss & Tell turned that convention on its head by setting them in an unexpected location (a woodworking shop) and revealing the presence of the male voyeur rather than simply implying it.

That last grouping prompted a lot of negative feedback. In one gallery, a viewer blacked out the figure of the man using sharp lines. Comments over the course of the exhibition’s tour included “I find the presence of the boy really disturbing,” which elicited this response: “He’s a man, not a boy. I couldn’t get sexually aroused in front of a man. I don’t draw any line because I would not want a photo of me fucking at all and a photo is a photo, not the act itself.”

Many commenters in the men’s book took issue with not being allowed to write on the walls. “Great show,” wrote one male viewer. “But I really think the impact and emotion would be better if men & women wrote on the wall.” Other men were appreciative of the exhibition, including H.L., who signed with two male symbols and noted: “Growing up male I’m still trying to get rid of a lot of crap about women being ‘sexless’ (i.e., not wanting it). I really enjoyed the photos and the comments (learned quite a bit). Thanks for not making this a woman-only space. I want to know how my sisters feel.” By taking lesbian sexuality out of the closet and displaying it for people to see and comment upon, Kiss & Tell furthered their goal of battling against lesbian invisibility.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements