Corpus Fugit 2002

Kiss & Tell, Corpus Fugit, 2002

Photographic projection from live performance

Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books, Burnaby

Kiss & Tell’s final performance, Corpus Fugit, was their most complex and sombre. First performed at Vancouver’s Festival House over three nights in March 2002, the piece functioned as a memento mori, an homage to loss and loneliness. Lizard Jones described the performance as being about “death and the disintegration of bodies. That liminal space that we all inhabit.” The ninety-minute performance included four alternating projections of video and photographs featuring images of flowers in various stages of decomposition, a sculpture of the interior of a house surrounded by trees, and papercut figures on handheld sticks. In a round-table interview, Persimmon Blackbridge described the projections this way: “We had light reflected on water, we had rain coming down on windshields and windshield wipers wiping it. We had salmon after spawning up the river, dying. We had Susan’s arms swimming. We had many, many video things.”

During Kiss & Tell’s fourteen-year existence, its members honed their compelling blend of performance art, theatrical productions, and immersive projections. The collective was very much ahead of its time in pushing the boundaries of performance and photography by fostering interactivity, projecting video and photographs, overlapping photos with text, and using unusual stage props (such as a sculptural miniature house and a full-size swing).

Corpus Fugit began with a humorous take on the story of the Rapture. Lizard, wearing a red wig, imagined how people in Vancouver would react to the Apocalypse. “We all ran out into the street thinking this is it, the big one, the earthquake… but it was the other big one,” she said. “On the sidewalks born-agains were falling to their knees singing ‘Hallelujah’ and the rest of us, sinners, just stood around looking at each other like, ‘No way, man—this cannot be happening. Armageddon!’” Two winged women took off Lizard’s wig while Susan Stewart, Persimmon, and collaborator Glenn Watts sang in a chorus line and did jazz hands.

Later in the piece, Susan delved into heartbreak from a devastating breakup. “Your words, the scalpel, start cutting away the stitches from my wounds,” she recounted while images of a desiccated fish against a velvet backdrop morphed into internal organs painted onto Lizard’s skin. The body on screen suddenly moved, bringing a still image to life. Susan drew connections between her pain and sitting at the deathbed of her father, a man she both admired and feared. She talked of his life in the military and of how he left her a mending machine that helped her metaphorically reconstruct her broken heart: “Once I got the knack of it, I did all kinds of repairs, covered up despair with a solid weave, needle in, needle out, pulling the threads tight. Wouldn’t call it fancy work, but the patches are holding.”

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

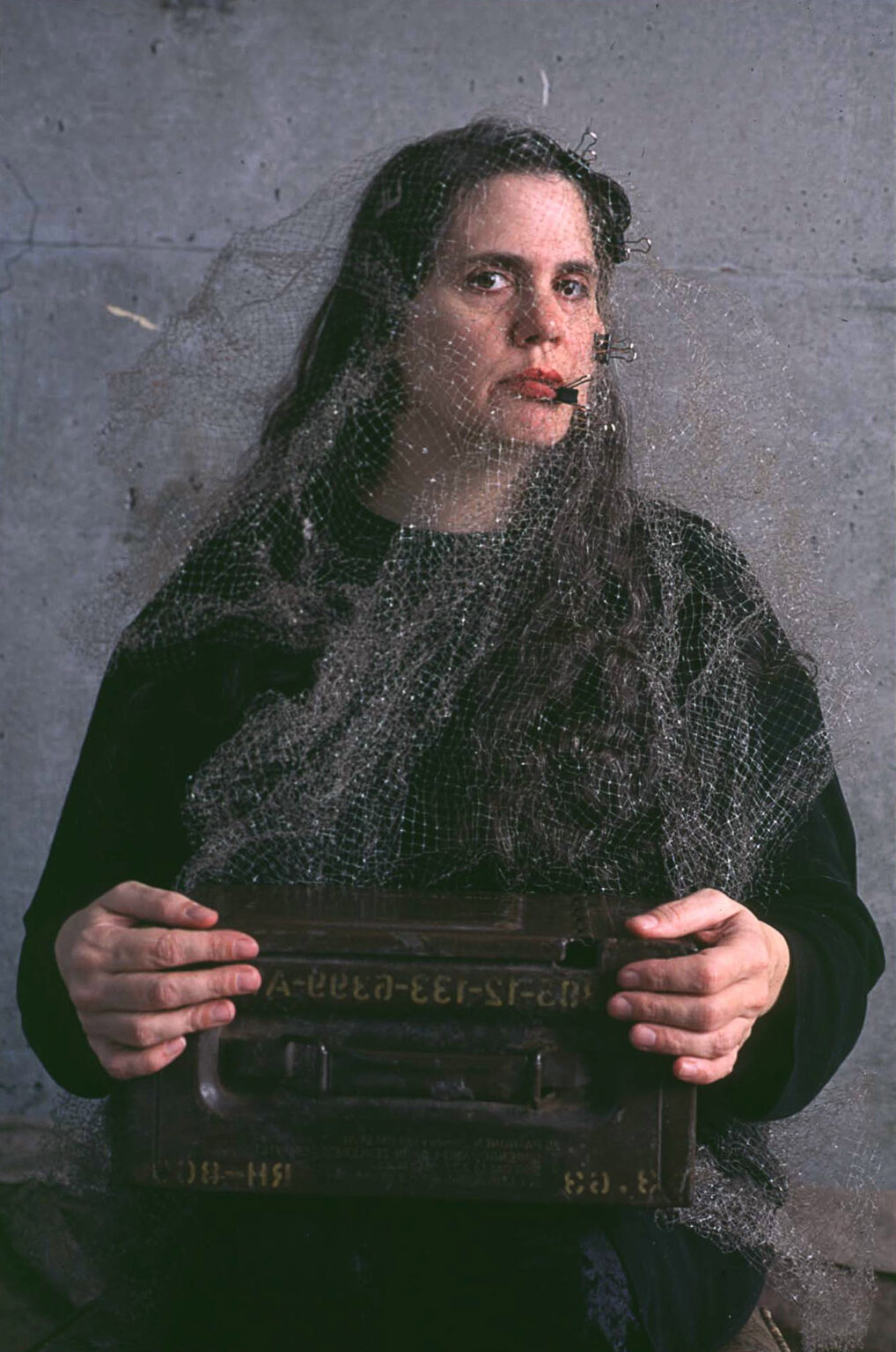

In Persimmon’s monologue, titled “Dead Dad,” she spoke about how her parents, who both died from cancer, spent their final moments. The story is long and difficult to listen to. She acknowledged that her relationship with her father, who was violent, wasn’t easy. With death looming, he asked her to find needles so he could inject himself with a lethal dose of morphine. The tale was told in a voice-over as Persimmon held a box of ammunition, her energy intense and sorrowful. When the collective performed Corpus Fugit at a conference on narratives of disease, disability, and trauma, Lizard remembered that during this scene, a woman started screaming. “The main thing was that she left the room, but the theatre was such that we could hear her running back and forth in the hallway behind the stage for a long time.” Persimmon kept going with her performance as the woman paced and screamed in the background.

In another poignant scene, Persimmon held Lizard in her lap like the Pietà while Susan brushed Persimmon’s long hair. This image was repeated in a projection of a photograph of Persimmon with skeletal makeup and Lizard nude with her organs painted on the outside of her body. Red and yellow lights flashed against their bodies as Watts played a melancholy tune on an accordion. The three artists sang while pulling long red pieces of textiles from their chests. It felt like the end of a Greek tragedy, with the chorus mourning and letting go.

The last line of Corpus Fugit was given to Susan. Dressed in black, the members of Kiss & Tell stood in a row and read from scripts on music stands. Persimmon and Lizard looked to Susan, who said, “When Compassion comes, she’ll stop our cries with a kiss.” The accordion played, Kiss & Tell took a bow for the last time, and the stage turned to black.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements