Kiss & Tell (1988–2002), the lesbian art and activist collective, pushed back against lesbian invisibility with its photography exhibitions, multimedia performances, and books. Its three members, Persimmon Blackbridge (b.1951), Lizard Jones (b.1961), and Susan Stewart (b.1952), met in Vancouver in the early 1980s and worked together for fourteen years. Initially galvanized by debates surrounding the ethics of pornography and by limited representations of lesbianism in popular culture, the three women publicly tackled questions central to feminism at the time, such as whether pornography is harmful to women. Encompassing experimental theatre and cutting-edge media art practices, Kiss & Tell’s groundbreaking works spoke from the margins, addressing issues of censorship, relationship and family dynamics, disability, and class struggle with humour, audacity, cleverness, and resilience.

Before and Beyond Kiss & Tell

Visual artists Persimmon Blackbridge and Susan Stewart and writer Emma Kivisild (a.k.a. Lizard Jones) came together in 1988 to form the Kiss & Tell collective. While they worked collaboratively until 2002, they also engaged in solo artistic and writing careers before, during, and after their time as Kiss & Tell.

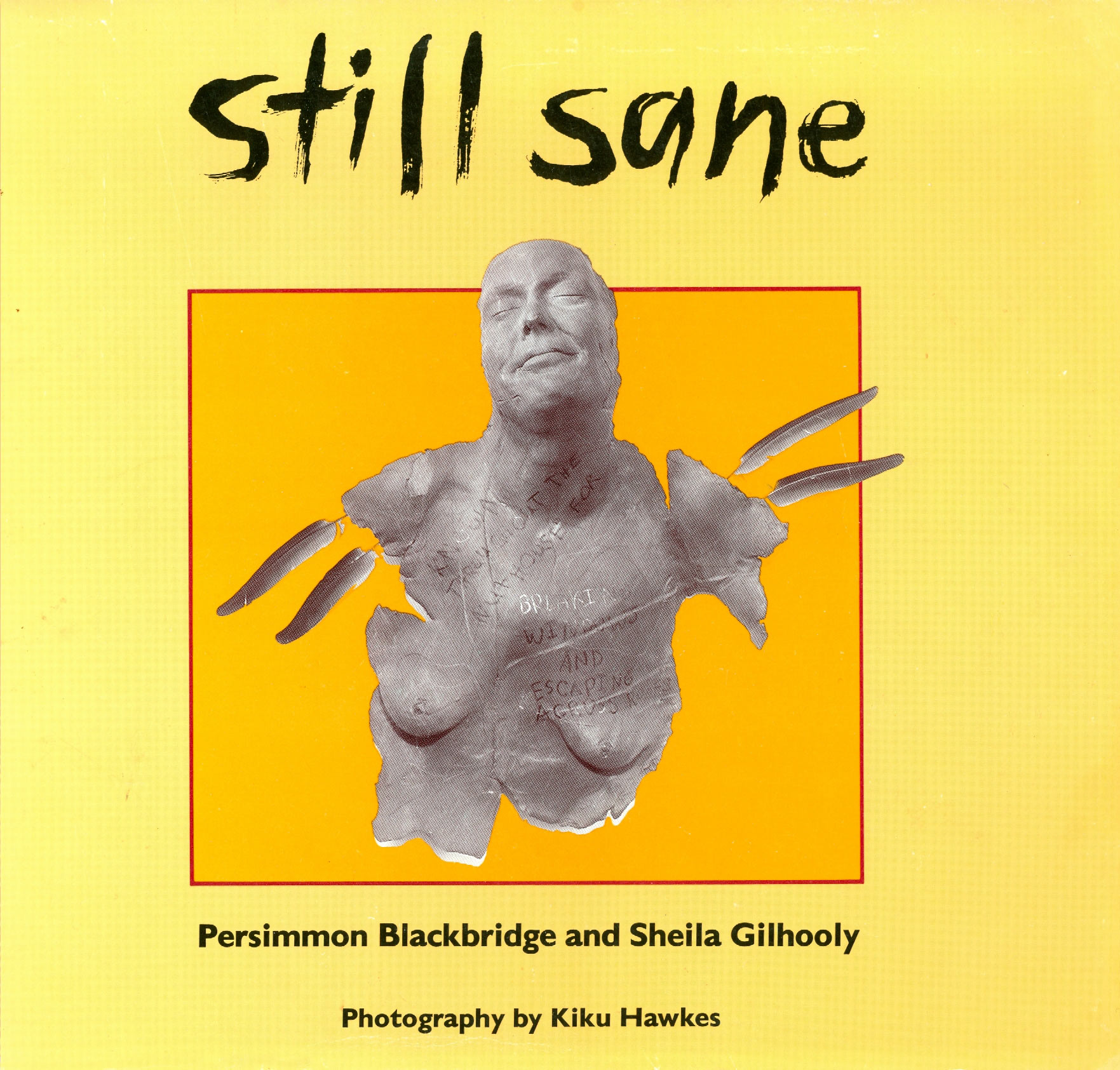

Born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1951 and based on Hornby Island in British Columbia, Persimmon Blackbridge is a sculptor, writer, curator, performer, and fiction editor. She began her career as an artist in the 1970s, creating works that addressed disability and mental health. Persimmon’s first major contribution to queer art in Canada happened in 1984, four years before the formation of Kiss & Tell, when she produced Still Sane, a collaborative sculpture and writing project with author Sheila Gilhooly (b.1951). The project was inspired by Gilhooly’s experience of being incarcerated in a psychiatric hospital after coming out as a lesbian. Still Sane consisted of twenty-seven life-size body casts made with clay, each accompanied with text written by Gilhooly. Many of the works created for Still Sane were exhibited as part of the Women, Art and Politics conference held at AKA Gallery (now AKA artist-run centre) in Saskatoon. The entire series was shown at Vancouver’s Women in Focus Gallery in the fall of 1984.

Persimmon’s decades-long work in disability arts continued during and after her time with Kiss & Tell. Her 1993 exhibition and book Sunnybrook focused on abuse at the Woodlands School in New Westminster, British Columbia, and won the Ferro-Grumley Award, a prestigious American LGBTQ literary award. Five years later, she collaborated with twenty-eight former inmates with intellectual disabilities on an exhibition titled From the Inside/Out. The project chronicled their lives in institutions across British Columbia and was a factor in gaining reparations for former residents of the Woodlands School.

Persimmon has stated that creating art about disability helped her understand the ways in which it affected her own life. “In my life,” she said, “disability was always something that you hid from people…. I hid my learning disabilities from people because I knew [they] made them treat me like I was stupid. I hid my own psychiatric history because I knew that would make people doubt my perceptions and reactions, it makes you a person who’s not taken as able to speak for themselves or understand what’s going on around them.“ Since embracing her role as the “old dyke auntie of the disability movement,“ Persimmon has continued to make work that disrupts conventional understandings of the arts in Canada. In 2015, she exhibited a series called Constructed Identities, which used mixed-media wood carving and found objects to question why disability is framed as a fracturing of ordinary life rather than a central part of it. Speak No (emergency), Persimmon’s installation about climate change, was exhibited at the Richmond Art Gallery in B.C. in early 2025.

During her time with Kiss & Tell, Emma Kivisild went by the pseudonym Lizard Jones. When asked why, she said, “I have a very, very recognizable Estonian last name—like, there are two families in Canada [with this surname]. Did I want my parents to deal with this? I wasn’t really out at that point.” Emma is a writer and artist living with multiple sclerosis (MS) in Prince Rupert, British Columbia. She was born in Vancouver in 1961 and spent her childhood in Taipei, Toronto, and Calgary. In 1977, she attended Princeton University and received a bachelor of philosophy of science. She completed her graduate studies in Vancouver at Simon Fraser University (SFU) and the University of British Columbia (UBC) with the support of a doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Her performance Hope against Hope: Looking Forward to the Apocalypse at the SFU Harbour Centre examined predictions of the end of the world.

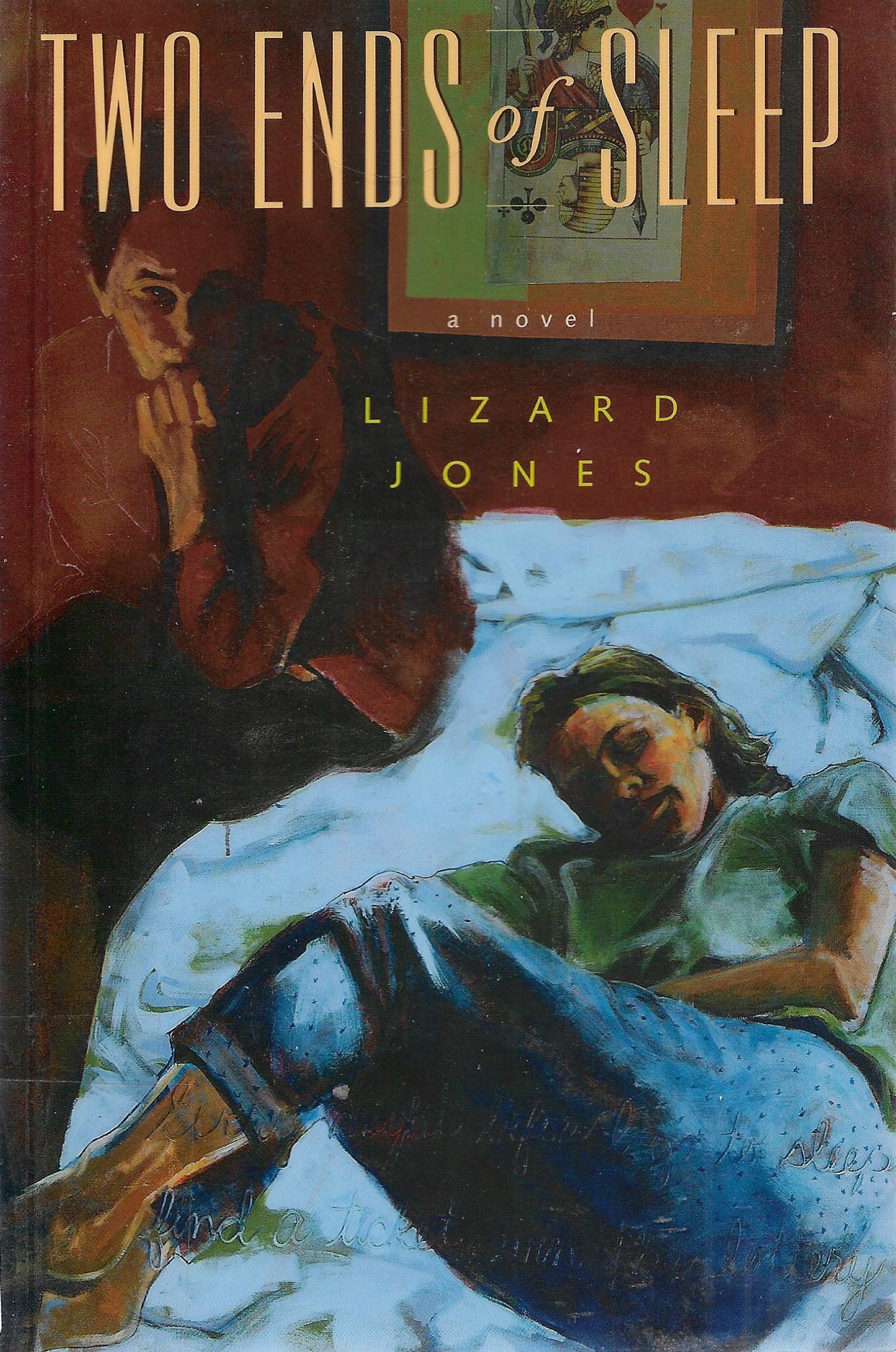

As a writer, Emma authored the 1997 novel Two Ends of Sleep, which explored her diagnosis of MS and life in the queer community. She was also a contributor to the Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies and the anthology Body Breakdowns: Tales of Illness & Recovery (2007). As an artist, she has participated in the Canadian disability art community with several shows and performances. From 2001 to 2012, many of her pieces, including Message in a Bottle, Waiting Room, Hoop Jumper, and Sow’s Purse: You can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, were exhibited at the Roundhouse, Pendulum, and InterUrban galleries in Vancouver. Each of these projects addressed the intersection of queerness, disability, and multiple sclerosis. In 2019, as part of the Sick + Twisted Cabaret in Winnipeg, Emma performed Sometimes When We Touch, which addressed intimacy and physical contact.

From 2013 to 2015, Emma was artistic director of Kickstart Disability Arts & Culture in Vancouver. In 2016, she moved to Prince Rupert, where she continues to work as a writer and an artist. Her short story “Limoncello” won the 2018 Paint Swatch competition in Northword Magazine, and her freelance writing has appeared in Northword, The Northern View, and Thimbleberry Magazine. She was on the board of the Prince Rupert Community Arts Council and currently sits on the accessibility committee of Prince Rupert city hall. For seven fun years, she was the mainstage emcee of the Vancouver Folk Music Festival.

A photographer and videographer with Kiss & Tell, Susan Stewart was born in Vermont in 1952 and immigrated to Canada twenty-one years later. Susan said her decision to leave the United States was propelled by her objection to the Vietnam War: “My identification with fighting for civil rights and the anti-war movement gave me passionate though incoherent political convictions and I just had to act on them.” Susan enrolled at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, where she was introduced to time-based media in courses taught by video artist Colin Campbell (1942–2001). She continued her study of lens-based media at the Alberta College of Art (now Alberta University of the Arts) in Calgary and at the Ontario College of Art and Design (now OCAD University) in Toronto, where she attended courses with Noel Harding (1945–2016). About building a career as an artist, Susan has said, “I realized I had two choices. I could have a place in the art world and base my art on pleasing myself and satisfying my own intellectual curiosity. The other option would be to direct my art toward social change. I could engage and act on my political convictions and put my work in conversation with culture and society. I chose the latter knowing I would be an outsider and marginalized within the art world.”

Susan identifies as a social practice artist concerned with social justice and enactments of resilience, working both inside and outside conventional institutions. Before she began working with Kiss & Tell, she was a practising studio artist and had been experimenting with “narrative fragments” and portraits depicting fraught and repressed desire using photography. Like Persimmon and Lizard, she was active in the Women’s Liberation Movement, as it was first known, before settling into feminist and queer activism. Following Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line, Susan’s photography exhibit Lovers & Warriors extended her work with the collective. Over a three-year period, she collaborated with twenty-one sex-positive genderqueers prioritizing diversity and inclusion. This work was exhibited in Vancouver and toured Germany in 1997.

In addition to her work with Kiss & Tell, Susan has forged a creative practice that revolves around ecological awareness and ethics, as well as Buddhism. In 2017, she participated in a residency program called the Arctic Circle, where she used photography to address human culpability in catastrophic ice loss. (She investigated a similar theme eight years earlier with her immersive video installation Change Without Notice, 2009, a project that investigated new modes of interconnectedness through durational media—evoked by layering multiple video projections.)

More recently, Susan has conducted image explorations of Buddhist pilgrimage sites in Canada and Asia, documenting the search for the sacred in an era of radical disconnection. The resulting video installation, titled Pilgrimage Boudhanath Stupa (Kathmandu, Nepal) Moraine Lake (Alberta, Canada), 2019, was presented in 2023 at the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff as part of the exhibition In the Present Moment: Buddhism, Contemporary Art, and Social Practice. Susan’s artistic life has always included forms of mentorship; a committed educator, she taught art and served as an administrator at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, where she is based, and was the founding dean of the school’s Faculty of Culture + Community.

Becoming Kiss & Tell

In September 1987, a poster created by Vancouver artist Laiwan (b.1961) for International Lesbian Week caused an uproar within the lesbian community. Published in the local queer newspaper, Angles, the poster featured a grid of sixteen black-and-white photographs of fragments of nude female bodies engaging in sexual acts. The bodies, alone and in pairs, were shown in close-up views that focused on the sex rather than the individuals participating in it. Curator Amy Kazymerchyk wrote about the poster: “In the 1980s it was dangerous to be a visible, vocal lesbian. So much so that Laiwan cropped the models’ faces from the photographs to protect them from public scrutiny, ostracization, and violence. Fearing the same retribution, she was credited under the pseudonym Li Yuen.”

Criticism from within Vancouver’s lesbian community was varied and included the erroneous assertion that all the women featured on the poster were white. While some observers celebrated the work for daring to put lesbian sex out in the open, many others took issue with the fact that the women’s faces were obscured and their bodies fragmented. Persimmon commented: “At that time in feminist theory… fragmentation was violence.” Because “lesbian scenes” had long been a staple of straight men’s commercial pornography, lesbian artists and activists in the feminist counterculture movement of the 1970s were sensitive to images that reduced women to their bodies. Fragmentation was equated with violence because it was seen as a patriarchal tool to show a woman’s body as a series of eroticized parts. But this theory would be refuted by a new generation of artists, including Kiss & Tell, who negotiated the politics of lesbian visibility by embracing sex positivity in their art. Reflecting on the outrage against Laiwan’s poster—one of the catalysts that brought together the members of Kiss & Tell—Persimmon defended the “intimacy of extreme close-up” as a way of protecting the women who had agreed to be part of the work.

Persimmon and Susan had met in 1984, when they joined Canadian video artist Sara Diamond (b.1954) and several other women artists to talk about sexual imagery and censorship. Those meetings transformed into a group that made exploratory art about sex. Canadian filmmaker, writer, and activist Marusya Bociurkiw described this group: “The women created a situation of openness in their group and prioritized explicit sexual conversation. They passed around images they liked, created what they called a ‘lust journal’ in which images and narratives were contributed anonymously… and told one another their complete sexual histories.” Lizard, a writer who had become friends with Susan in Calgary via feminist activist circles, often attended meetings while babysitting Susan’s child.

When Laiwan’s poster came under scrutiny, Susan reached out to the members of the former art-and-discussion group to dissect the uproar. Wholly engaged in the resulting conversations, Persimmon, Lizard, and Susan decided to form an art collective that would address issues of queer lived experiences and sexual representation within Vancouver’s lesbian community and beyond.

The artists’ decision to band together and create socially engaged art was timely because Canadian queers had weathered conservative backlash for decades, from the Canadian government’s purges of gay and lesbian civil servants and military personnel to homophobic responses to the AIDS crisis. Diverse representations of women loving women were sorely needed to combat institutional violence, stigmatization, and moral panic. As Susan wrote in Kiss & Tell’s co-authored 1994 book, Her Tongue on My Theory: Images, Essays and Fantasies, “Lesbian photographs (published and unpublished) get circulated, passed hand to hand, discussed and debated within the community. There is a tremendous demand and need for self-representation by a community whose psychic survival depends on the sure knowledge that there are others like ourselves.”

Persimmon, Lizard, and Susan initially responded to debates about the scarcity of queer representations made by queer people within and beyond the lesbian community. They continued to collaborate because they were united in their fight for social change and justice. They were tuned in to the intellectual projects of radical thinkers, and they read everything from the foundational works of anarchist Emma Goldman and second-wave feminists Adrienne Rich and Angela Davis to Paulo Freire’s 1970 Pedagogy of the Oppressed and writings by critics such as Susan Sontag and Monique Wittig. The artists made it their mission to destigmatize lesbian desire, to build community, and to begin to heal from the trauma perpetuated by a society that had demonized lesbianism for so long.

The artists landed on the name Kiss & Tell, a play on the outdated expression “A lady doesn’t kiss and tell.” This appropriation seems particularly apt for lesbians who had once stayed in the closet rather than risk losing their jobs, families, religious communities, children, homes, and friends. The women of Kiss & Tell kissed and told. They recounted their sexual exploits and fantasies, bringing lesbian sexuality out of the closet and into the public realm.

Between 1988 and 2002, Kiss & Tell created a touring photography exhibition and four multimedia performance works. They published two books and wrote a twenty-eight-minute film, directed by Vancouver filmmaker Lorna Boschman (b.1955). (They also collaborated with her on two other videos.) But despite their trailblazing body of work, little has been written about Kiss & Tell’s oeuvre and how radical they were for their time, and there is little information about them online. Their provocative photographs of lesbian sex captured audiences, and once they had that attention, they continued to “complicate the narrative to include class analysis, trauma, ableism, sexism, oppressive political systems/laws, and love.” The collective experimented with a variety of media to create art that spoke back to power. They never shied away from making images that might be received negatively, and they constantly pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable, despite the risks.

A Collaborative Approach to Lesbian Visibility

“For lesbians, invisibility has been our safety and our trap,” wrote Kiss & Tell in their 1994 book, Her Tongue on My Theory: Images, Essays and Fantasies. “Being in the closet may be stifling, but it could save you from losing your job, your children, your life. It’s frightening to leave that trap. When other lesbians do it, it can feel like they’re endangering us all, giving us all a bad name. Sometimes we are quicker to punish each other than the outside world.” By making work that was distinctively and openly lesbian, Kiss & Tell sought to combat invisibility and discrimination.

The first Canadian law condemning homosexuality was enacted in 1841. In 1890, “gross indecency between male persons” became a crime; it was extended to lesbians in 1953. Homosexuality wasn’t decriminalized in Canada until 1969, and even then, only partially (parties had to be twenty-one or older). It was only in 1996 that the Canadian Human Rights Act was amended to include sexual orientation as prohibited grounds for discrimination. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, out lesbians in Canada still risked social stigma, violence, job loss, institutionalization, insecure housing, and loss of child custody. Being forced to hide their identities contributed to a lack of lesbian representations made by lesbians.

Lesbian invisibility and erasure persist, especially in Canadian art history. How many lesbian visual artists can you name? When I ask my undergraduate students this question at the beginning of a Canadian art survey course, the vast majority are unable to do so. Feminist art historians have worked tirelessly to bring women artists from the margins into galleries, museums, and the canons of art history. Much of their work has been intersectional, accounting for race, gender, ethnicity, class, disability, embodiment, and sexual identity when criticizing women’s exclusion from the male-dominant discipline. But as Susan writes in Her Tongue on My Theory, “women artists have had to fight and push for every bit of ground they can claim in the high-stakes game of recognition, support, and success in ‘the art world.’ For lesbian artists, this slice of the pie is smaller yet, with even more shut doors, glass ceilings, and heterosexist barriers.”

Despite institutional erasure, many queer women artists during the second wave of feminism made it their mission to exhibit works focused on their lesbian identities. Still, some lesbian artists in the 1970s and 1980s were reluctant to participate in exhibitions explicitly labelled as lesbian. For example, when American artist and curator Harmony Hammond (b.1944) mounted The Lesbian Show in 1978—the first U.S. exhibition to include work solely by out lesbian artists—many of those invited to take part declined because they feared it might negatively impact their careers. In 2000, Hammond published her groundbreaking book Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History—still the only art historical survey about lesbian American art to be published to date. Hammond wrote the book so the work of queer women artists from the 1970s to the 1990s would be recognized and remembered. “We cannot afford to be silent or to let others decide what kind of art we may or may not make,” she asserted, “nor let our creative work be ignored, ‘straightened,’ dehistoricized, decontextualized, or erased.” No similar survey book has been written about Canadian lesbian artists.

Outside the Canadian academy and art institutions, Kiss & Tell found strength, camaraderie, and support within feminist and lesbian communities. Like many lesbian artists of their generation, they learned how to collaborate by participating in feminist grassroots activist organizations. In Vancouver, the artist-run centres embraced the ideas of radical socialist political movements, and fought for women’s equality, queer liberation, and Indigenous rights. Many artists were drawn to spaces where they could exhibit works that emphasized their politics. When Intermedia, Vancouver’s first artist-run centre, disbanded in 1972, many more organizations were founded in its wake, including the Or Gallery (founded by Laiwan), the grunt gallery, the Western Front, and Women in Focus Gallery. The latter two were strong supporters of Kiss & Tell. Women in Focus’s public gallery space became the venue for the collective’s first photo exhibition, Drawing the Line, in 1988. These centres, and many others, operated with mandates that combined art and politics. The members of Kiss & Tell brought this grassroots emphasis on politics and activism into their creative practice.

Working together, with other artist-collaborators, and in dialogue with activist peers, Kiss & Tell questioned and created alternatives to a hegemonic male gaze that saw women only as sexual objects. The collective represented lesbian desire as empowerment and lesbian sexuality as a space for play, intimacy, discussion, role play, experimentation, fun, power exchange, sensations, orgasms, and connections. “We start by riffing off ideas from each other but then begins the conversing, wrestling, and dealing with one’s attachment to ideas,” said Susan about the collective’s creative process. “It takes time to process ideas collectively as you must go through a psychological and spiritual change. You must develop a generosity of spirit.” For Persimmon, collaboration heightened the formal experience of the work: “The thrill of collaborating… is the way we all three are in love with both form and chaos. Our performances are unstable structures that create meaning by juxtaposing chaotic images and stories. Meaning is never actually defined or stated, never nailed into place. Everything is always shifting—like our lives.”

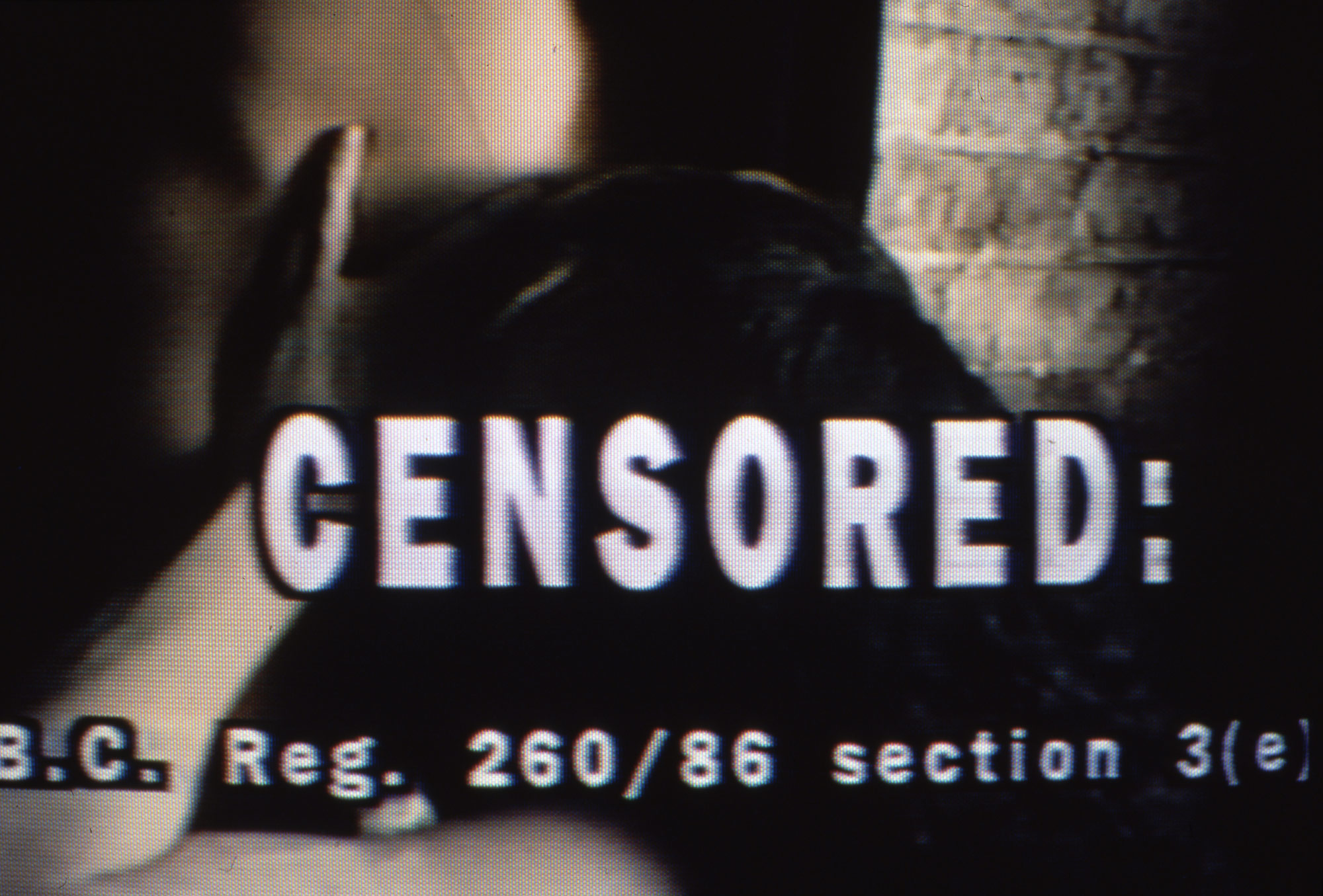

An example of Kiss & Tell’s collaborative approach to experimentation is seen in the twenty-eight-minute video True Inversions, 1992, that accompanied their performance of the same name. Written by Kiss & Tell and directed by Lorna Boschman, the video intercuts masturbation and fantasy sequences with behind-the-scenes discussions with the cast and crew. In one scene, Lizard and Persimmon can be seen making out on a swing—an object that also appears on stage in the True Inversions live performance—while one of their camerapeople, author and visual artist Shani Mootoo (b.1957), says, “Most people with privilege are not aware of when certain people are being oppressed, and it is really important for those things to be called out and that’s different from censoring. Censorship implies that there is a penalty. It has more to do with things being prevented by law.” Like much of Kiss & Tell’s work, the True Inversions video was self-referential and commented on events and issues that impacted their personal and creative lives. True Inversions sought to complicate discourses of power, pleasure, and censorship by drawing attention to the framing power of the camera and the director.

Kiss & Tell’s collaborative creative processes were built from shared politics. Their aim to make transformative, conceptually complex work aligned with approaches taken by some of their queer contemporaries. As Canadian artist Shawna Dempsey (b.1963) has stated: “It is no coincidence that so much contemporary Canadian lesbian artwork is collaborative. The double marginalization of gender and sexual orientation makes voicing our positions difficult, and indeed dangerous. Do I have a right to speak? What is my language? How much abuse will I incur for being too visible?” Since 1989, Dempsey has collaborated on performance works with Lorri Millan (b.1965). Like Kiss & Tell, the duo privilege collective authorship as an artistic strategy, a radical act that undermines the patriarchal and capitalist structures of the art world. Rather than centring the individual artist (read: male, straight, and white) as a solitary genius, collaboration allowed for the creation of more nuanced and multivalent artworks.

Cover of Rites: For Lesbian and Gay Liberation 5, no. 8 (February 1989), Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby.

Queer writers and editors during this time were also working toward increased lesbian visibility. Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, Canadians could purchase queer magazines made in Canada, including The Body Politic and Rites. During her time with Kiss & Tell, Lizard was an editor and writer for the national feminist newspaper Kinesis. Vancouver’s Angles was another significant venue for building queer solidarities. The 1990 founding of the U.S. lesbian magazine Deneuve, which later became Curve, was another important milestone. The publication touched on many facets of lesbian culture—including marriage equality, genderqueer fashion, and cybersex—long before these topics became mainstream. Its founder, Franco Stevens, noted that having the word “lesbian”

on the cover was controversial because “that meant every time somebody wanted to buy it, they were essentially coming out to anyone standing around them, anyone who saw it in their house.” Although the magazine initially had trouble securing advertisers and subjects for its covers, its first issue sold out in six days. Queer women in the early 1990s were hungry for representation on their own terms—and it was finally beginning to happen.

Making Provocative Photographs

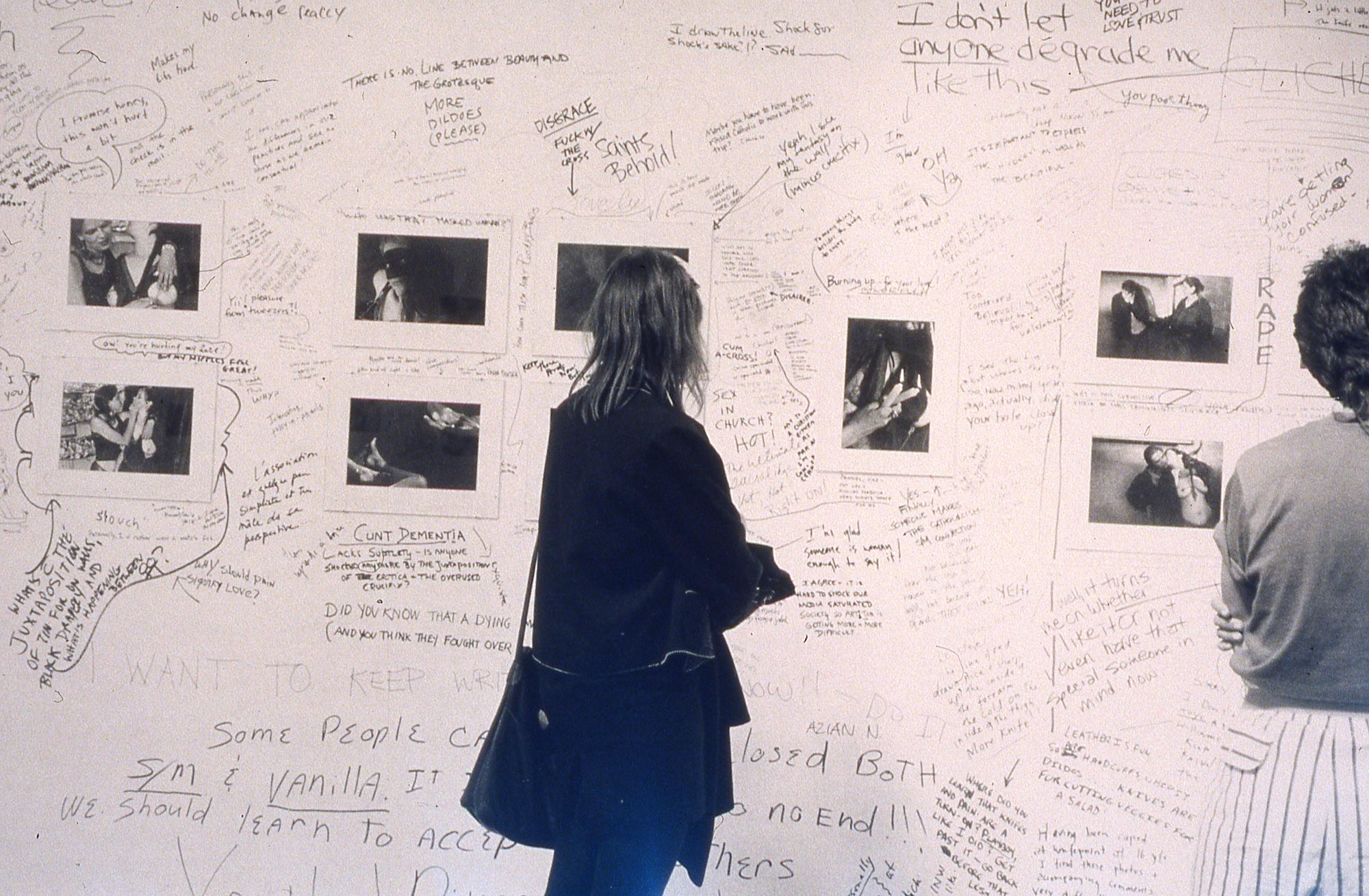

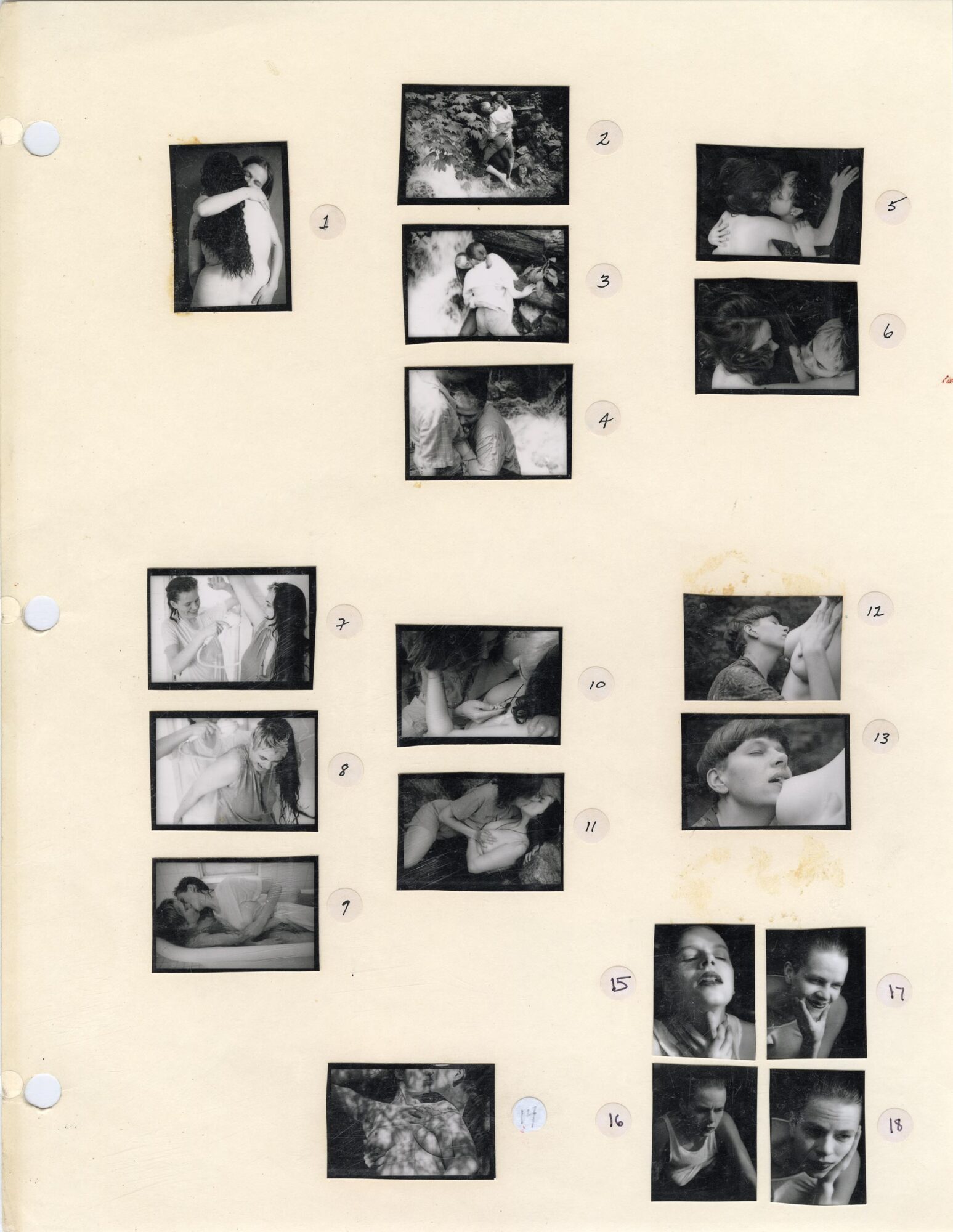

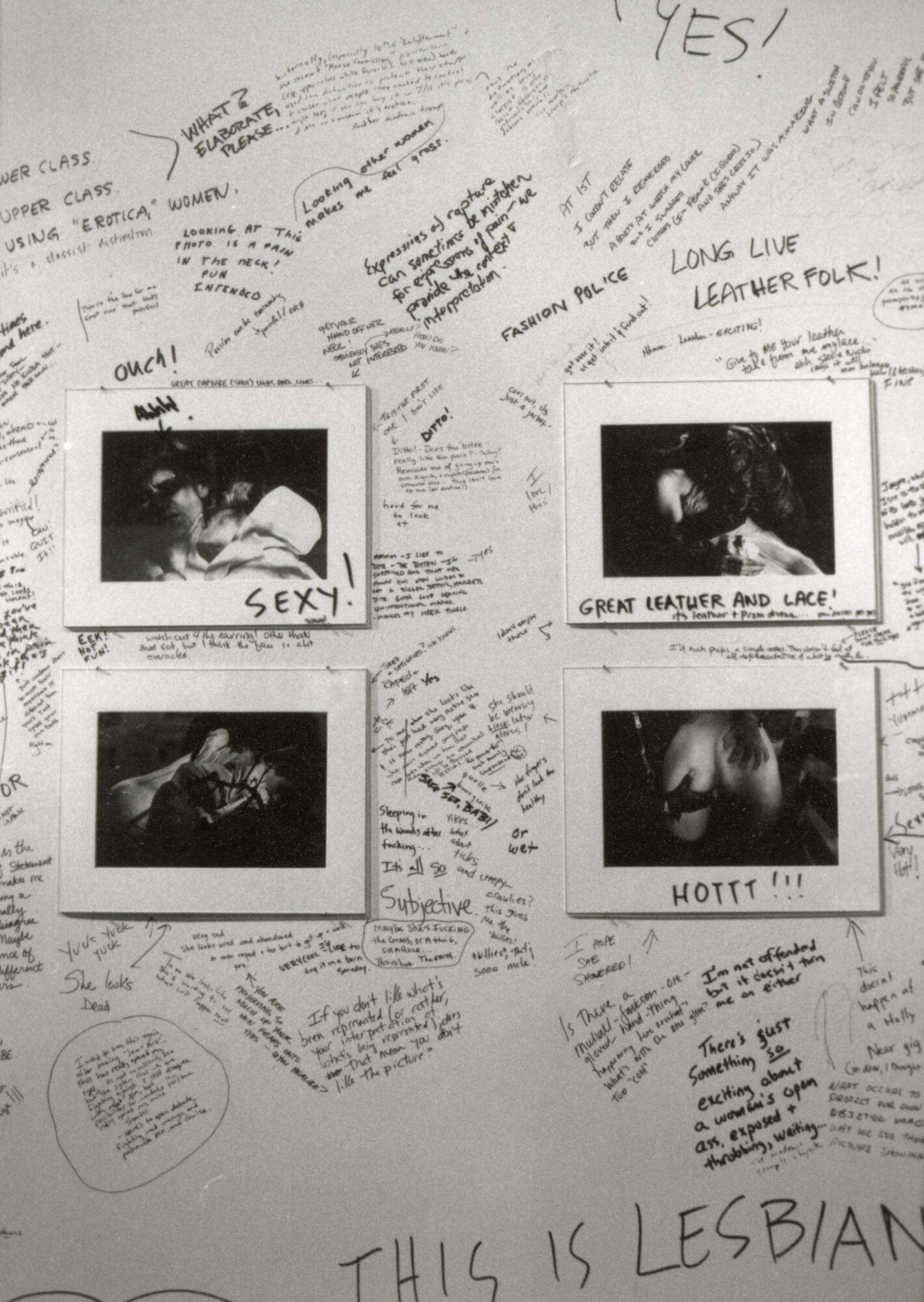

The last thing Kiss & Tell expected from their first exhibition was a line stretching for three city blocks. With hindsight, it’s easy to see why women (and lesbians in particular) were so eager to visit this exhibition at Vancouver’s Women in Focus Gallery in 1988. Those waiting in line were clamouring to see images of lesbians made by lesbians in an era when that was sorely lacking in art, news, media, and popular culture. Kiss & Tell’s Drawing the Line project, 1988–90, began with forty images and ended with ninety-eight black-and-white photographs of lesbian sexual practices. Shot by Susan, with Persimmon and Lizard as models, the images ranged from cuddling and kissing to BDSM and male voyeurism.

Drawing the Line was groundbreaking not only because Kiss & Tell dared to display sexual photographs in public but also because they invited women viewers to respond to the photographs by writing directly on the gallery walls. Men had to leave their comments in a guest book. “It was important to separate the genders to enable women to feel confident being on the fence on the sexuality issue,” Lizard explained. “Women were being told what they thought, and felt, [by men], and the only way to clarify things was to keep men out of the discussion. It was the only way to find out what women actually felt.” The walls of the exhibition quickly filled up with comments, drawings, and debates. Some viewers even went so far as to draw and write on the photographs themselves. Drawing the Line marked the beginning of Kiss & Tell’s fourteen-year project to build community, an endeavour that brought them into dialogue with lesbians, feminists, political activists, and cultural theorists of many stripes.

After its debut in Vancouver, the exhibition toured Canada, the U.S., Australia, and the Netherlands. It drew attention to questions that many feminists were asking at the time, such as how the debate around pornography and erotica changes if the sexual images are created by women for women. One way that the members of Kiss & Tell sought to address these questions was by collaborating with each other and the audience. Susan talks about the importance of making art as a collective:

I think we started complicating meaning right in the beginning with Drawing the Line—we really worked around any easy reading of anything we did. And that’s what was great about having three of us, because with three different artists contributing, it’s not a singular vision…. And we needed each other badly when we did this work. At the time, it was so edgy to be putting this out there. It felt very dangerous. I could have never done it without [Lizard and Persimmon].

Exhibiting Drawing the Line carried significant risk. In Susan’s case, she was terrified her young child might be taken away from her. Her fear wasn’t unfounded. Canadian lawyer Joanna Radbord, writing in 1999 about lesbian mothers and custody, stated: “Judges have frequently distinguished between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ lesbian mothers on the basis of whether the mother is closeted and ‘discreet.’” To this day, there are still cases of Canadian lesbian mothers who are denied custody and granted only limited access to their children.

The photographs in Drawing the Line were arranged to form narrative fragments that explored complex relationships between desire, sex, transgression, rage, and freedom. In each photograph, Kiss & Tell engaged with the formal conventions of the camera. Framing was one tool the artists used to make audiences question their relationship to the images. In some photos, the camera zoomed in tight, focusing on parts of Lizard’s and Persimmon’s bodies as they writhed in pleasure. In others, the camera took in the women’s entire bodies or situated them within their surroundings. The artists used the camera to consciously expose how lesbians see and are seen. They questioned what kinds of images are constructed as “lesbian,” exploring a query expressed by artist and curator Harmony Hammond: “Is the quality ‘lesbian’ embodied in the art object, the sexuality of the artist or the viewer, or the viewing context?” The answer for Kiss & Tell was any or all of the above.

Audiences found it difficult to draw a definitive line between the photographs that could be construed as erotica, including one of two fully clothed women embracing and kissing beside a waterfall, and those that might be considered pornographic, such as a photograph of Lizard fisting Persimmon. Each photograph drew a range of responses that demonstrated how viewers’ opinions weren’t as monolithic as one might assume given the binary enforced by some feminist critics at the time. A 1988 review of the exhibition at Vancouver’s Women in Focus Gallery described the interactions: “The abundance of comments compared to the drawn lines indicated that what is personally erotic is complex and cannot be graded on someone else’s scale.” For example, when a photograph of two kissing women (one of whom is bare chested) was exhibited in Sydney, Australia, the comment thread started with “Great tits!,” was followed by “If we say, ‘great tits,’ aren’t we just copying the patriarchal way of fetishizing bits and pieces and ignoring the woman as a whole?,” and ended with “Can’t we just admire her tits? Is this a crime?”

Drawing the Line was pioneering and subversive not just because it unabashedly depicted lesbian sex. In featuring middle-aged bodies of different sizes, the project provided an alternative to mainstream sexual imagery that only celebrated the bodies of thin young women. As Persimmon stated in Kiss & Tell’s 1994 co-authored book, Her Tongue on My Theory: Images, Essays and Fantasies:

On the covers of women’s magazines in every supermarket check-out line, we see extremely provocative and sexualized pictures of half-clothed women…. In North American culture, these images shape most (lesbian as well as straight) women’s ways of seeing sexualized pictures of other women, as well as our relationships with our own bodies. When I put my plump, 40-year-old body in front of the camera, this is the context I am addressing: a very different context from that of the straight male consumers of commercial porn.

Kiss & Tell refuted the stereotype that older women aren’t desirable or sexual. They highlighted their desires, and what might be desirable to other women, with bold and celebratory acts of disclosure.

Transgressive and Experimental Performances

In 1991, Kiss & Tell produced their first public performance during a conference talk at a Holiday Inn in Vancouver. For Drawing the Line, 1988–90, only Persimmon and Lizard got naked for the camera. They teased Susan that she never got naked for their art, so while Susan presented a paper, Lizard and Persimmon consensually undressed her slowly until all she wore was a strap-on. “I had a leather harness with a dildo,” Susan recounted. “And that’s it. And they just stripped me down completely. And I just read an academic paper. And then they put my clothes back on.”

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

-

Kiss & Tell, photographic projections from Corpus Fugit, 2002

Multimedia performance

Kiss & Tell Fonds, Special Collections and Rare Books, Simon Fraser University Library, Burnaby

Monologues, confessionals, and humorous anecdotes were at the heart of Kiss & Tell’s multimedia performances. They mixed storytelling with photography and video projections and music to provoke and connect with audiences and as strategies for experimentation. The energy at a Kiss & Tell performance was electric. Dance and performance artist Margaret Dragu (b.1953) described their final performance, Corpus Fugit, 2002, as “like sharing last night’s vivid dream with someone who is neither your therapist nor your lover. You gush inarticulately ‘… well, like, there are three women, right, and they talk and talk and, like, there are slides of the Berlin Wall and dying flowers and, oh, yeah, a video of this painting and it is breathing, and you know, these women are so funny—they tell real stories—sexy, sad, political—and all three of them are really, really, hot.’”

Performance art emerged in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s in tandem with the establishment of artist-run centres—or “parallel galleries,” as they were then called, a reference to their existence outside the official infrastructure for the arts. Many artist-run centres supported programming for music, dance, theatre, media art, and the visual arts, making them welcome spaces for the multidisciplinary nature of performance art. As a renewed and expanding art form from the 1960s into the 1990s, performance was taken up by many women who, like Kiss & Tell, wanted to disregard the standards and confines of the mainstream art world. In conceptualizing their transgressive and experimental works, Kiss & Tell turned to diverse references, including the avant-garde performances of Dadaist poet Emmy Hennings (1885–1948), the body art works of Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019), the deconstruction of the social expectations of women found in the work of Martha Rosler (b.1943), and the protest art of the Guerilla Girls (formed in 1985). Kiss & Tell also embraced strategies pioneered by experimental theatre groups such as the New York City–based Living Theatre and Montreal’s Theatre 1, along with the radical street theatre techniques used by the AIDS activist group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power).

Kiss & Tell included sexual imagery and stories in their performances to grab the audience’s attention and deliver a broader critique of what reviewer Caterina Pizanias called “the systems of signification within which sex, gender, race, and wellness/illness are performed.” Sexy stories of longing were sprinkled throughout Kiss & Tell’s performance That Long Distance Feeling: Perverts, Politics & Prozac, 1997. Two humorous phone-sex sessions, with Lizard as the client and Persimmon as the sex worker, were filled with titillating repartee. In one of these encounters, Susan tied a white scarf around Lizard’s eyes (reminiscent of the bondage photographs in Drawing the Line) while Persimmon, as the phone-sex worker, told a tale about a sexual interlude between “your lover and her other lover…. They’re having such a good time, and you can’t even touch yourself.”

The monologues were juxtaposed with onstage visuals (often video and photographic projections), music, and other physical props that connected sex to ethics, politics, embodiment, class, disability, gender, race, identity, and art. One reviewer of That Long Distance Feeling noted: “In a series of personal recollections, rants, vignettes, fantasies, and parodical social commentary, [Kiss & Tell] engage in the logic of time (social and personal changes of the last thirty years) and space (the post-industrial inner city) while reflecting the old dicta, ‘the personal is political.’”

Kiss & Tell mined their personal experiences for content for their performances. One section in True Inversions, 1992, tackled familial relationships and included letters that the members had written to their mothers but never sent. Lizard’s letter read, in part, “When you’re a lesbian there is no turning back…. We lesbians have a past. No one wants it, but it’s ours…. The desire still outweighs the risks. I live in a community of people who have chosen to follow their desires.” The trio returned to discussing family in their final performance, Corpus Fugit, where both Susan and Persimmon talked about the deaths of their fathers.

Their performances were often self-referential and tackled issues pertaining to the censorship of queer art and publications in Canada. In a review of their first performance of True Inversions at Vancouver’s York Theatre on April 11, 1992, Heather Reiger wrote: “The power of True Inversions was in its manipulation of juxtapositions: censorship vs pleasure, desire vs sexual abuse and religion, lesbianism vs family. The mixed media form used in the performance was extremely effective in portraying these juxtapositions.” Kiss & Tell saw their performances as opportunities to frame conversations among themselves and within their communities. Both the content and the form of their work supported the way they engaged with the world around them: critiquing, dissecting, and laying bare oppression in its many insidious varieties. Their visuals and stories were provocative and evocative—and at times brave—but they were also formally and conceptually ahead of their time. Kiss & Tell refused to remain unheard, and their performances, presented outside gallery walls, evoked pleasure, understanding, and even turmoil in their audiences of queers and allies.

Burgeoning Lesbian Art Scenes

In depicting aspects of lesbian sexualities openly and positively, exhibiting works in numerous venues across multiple countries, and inviting debate about lesbian sexual practices and representation, Kiss & Tell were well ahead of their time. As American artist and curator Harmony Hammond wrote in Lesbian Art in America: “Lesbian expression and self-representation continue to play an important role in keeping the w(hole) lesbian in all her fluid, layered, messy, and unruly manifestations intact—sexual, creative, political, and powerful.” Kiss & Tell brought the multiplicity of lesbian identities described by Hammond to the forefront by creating artworks and spaces where women could finally see themselves represented through a queer female gaze. The collective was part of a new and increasingly vocal wave of lesbian representation led by queer women in the 1990s.

In the U.S., lesbian art collectives such as fierce pussy, which formed in New York City in 1991, brought “lesbian identity and visibility directly into the streets.” One of their tactics was to create and display posters in public areas with slogans such as “I AM A lezzie/butch/pervert/girlfriend/bulldagger/sister/dyke AND PROUD!” and “Lesbian chic. My ass. Fuck 15 minutes of fame. We demand our civil rights. Now.” As Lauren O’Neill Butler wrote in Artforum: “fierce pussy strongly encouraged people to take, copy, and distribute its pieces, and so its production can be placed squarely in the genealogy of the multiple while also anticipating the logic of the self-propagating digital meme.” Just as Kiss & Tell encouraged women to share their opinions about the photographs in Drawing the Line, 1988–90, fierce pussy encouraged public engagement and made lesbian identities more visible via the proliferation of ready-made posters.

Created the same year as fierce pussy, the American lesbian art collective Dyke Action Machine (DAM!) was founded by artist Carrie Moyer (b.1960) and photographer Sue Schaffner. DAM! brought lesbian identities into the public sphere through billboards, light boxes, matchbooks, buttons, stickers, and posters. Each month, they wheatpasted five thousand posters in neighbourhoods with significant pedestrian traffic. In a 1992 campaign, members riffed on ads in Family Circle magazine by placing images of diverse lesbian families on posters that read, “Dykes were family by golly, before families became trendy.” Two years later, in response to the U.S. military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy, DAM! created a poster promoting a fictional film called Straight to Hell and featuring images of BIPOC women to draw attention to how lesbians of colour were being expelled at a higher rate than white soldiers. The text read, “She came out. So the Army kicked her out. Now she’s out for blood.”

Like DAM! and fierce pussy, Kiss & Tell explored the intersections of the personal and the political, often with a sense of humour. In their performance That Long Distance Feeling: Perverts, Politics & Prozac, 1997, Lizard said: “Well, you know they say every revolution needs its artists. Here we are! I really like to match it up, you know, the personal and the political. Arise, ye prisoners of starvation / My girlfriend’s fucking someone else. What I want to know is when we storm the presidential palace, are we going to be putting up lesbian sex photos? Because if we are, I could supply them.” The audience responded with raucous laughter. Humour was deployed as a mechanism for uncovering social truths. “At the very root [of our work]… was trauma,” the artists explained. “We pushed into the edges of collective trauma by exposing our own, and allowing for a little release. Dressing this up in sexiness, flirtation, laughter and fun was what made it healing in a way.”

In 2015—more than twenty-five years after Kiss & Tell debuted their groundbreaking photography exhibition Drawing the Line—Lizard reflected on how the collective had helped propel the feminist and lesbian movement forward. “These images were difficult to look at for some, but art has always been about challenging people and sexual images have always been created by the art world,” she said. “The purpose of art is to look differently at the world around you, and you can’t do that without opening up and exploring.”

The same year, Vancouver’s Queer Arts Festival delved into the historical significance of Kiss & Tell when it showed a selection of the Drawing the Line photographs as part of an exhibition titled Trigger: Drawing the Line in 2015. In an interview with The Georgia Straight, curator SD Holman spoke about the influential yet largely unknown collective and their work. “Not a lot of people know about this unless they’re a dyke of a certain age,” Holman observed, “and I just thought if it was any other medium, or even some white guys, they’d probably have a statue in Vancouver, quite frankly.” For the exhibition, the festival asked Vancouver artists Afuwa, Bryan Bone, James Diamond, Suzo Hickey, Toni Latour, Jono Nobles, Coral Short, and Jonny Sopotiuk to create artworks in response to Kiss & Tell’s iconic photographs. Some explored topics such as religion, BDSM, and disability, while others drew connections with the queer artists who preceded them.

By creating art that openly represented lesbian desire, identities, and lived experiences, Kiss & Tell gave their fellow artists—and queer women—something they had never seen before. In 2002, after fourteen years of making work together, Kiss & Tell agreed they had accomplished what they set out to do and disbanded. Like many lesbians after a breakup, they remain good friends who continue to support each other.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements