Margaret Watkins (1884–1969) was at the forefront of advertising photography in the 1920s, shaping a new generation of practitioners through her teaching, exhibitions, and publications. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, she eventually made New York City her home, producing internationally award-winning still-life studies of domestic objects from her flat in Greenwich Village. She went on to capture the urban and industrial landscapes of European cities in the 1930s, living in relative obscurity in Glasgow for her last decades. Though she fell out of the public eye in her final years, today, Watkins is recognized as a pioneering modernist photographer.

Hamilton, Ontario, 1884–1908

In a 1923 letter to a publicity agent in New York, Margaret Watkins declared she had been “brought up on pictures and music.” However, as a warning to any potential biographer, she also wrote: “Living is a most vital and untidy business… I don’t want it all slicked up and streamlined.” In the spirit of her request, this biographical account will do justice to her creative achievements and also to the messiness of life.

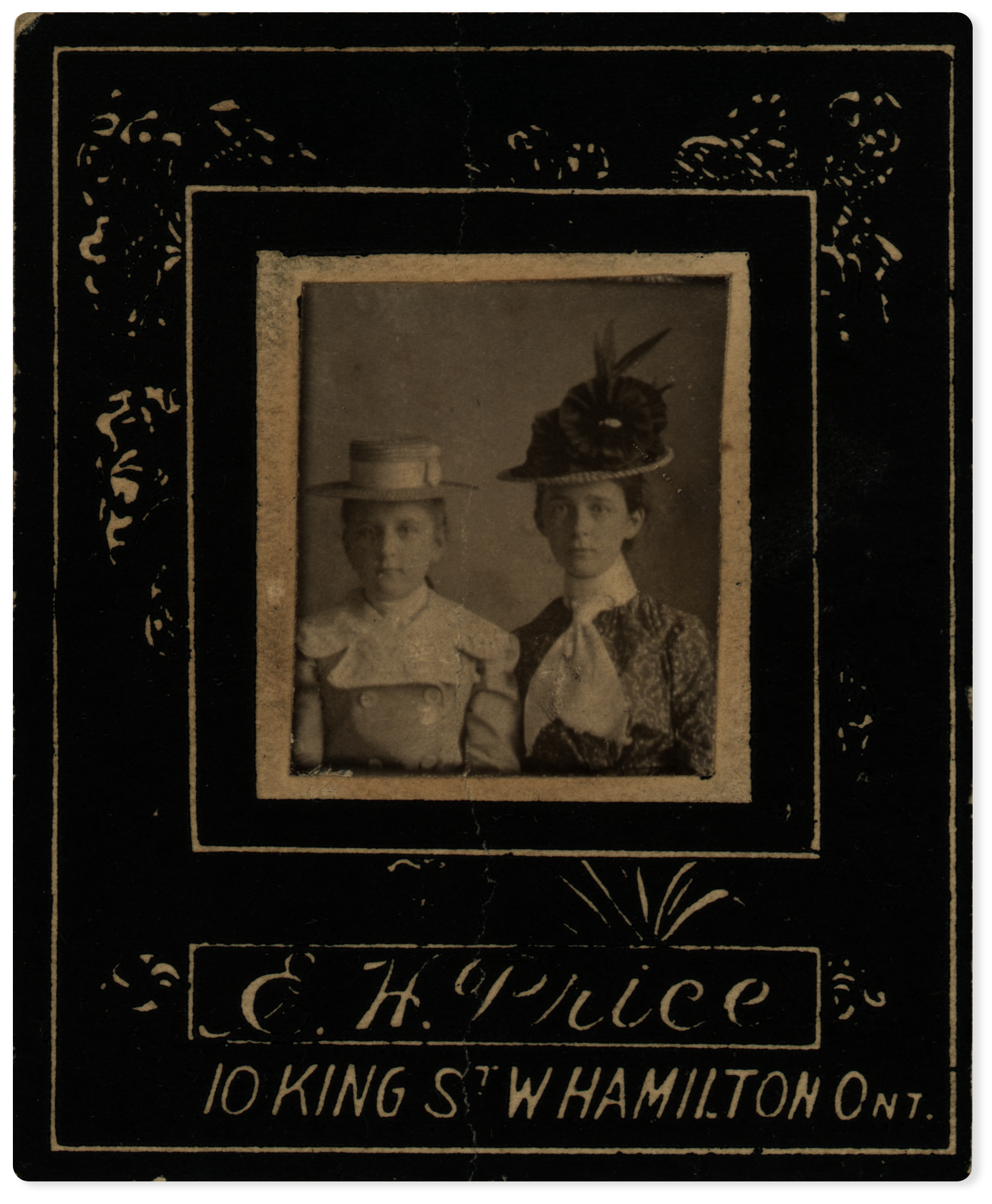

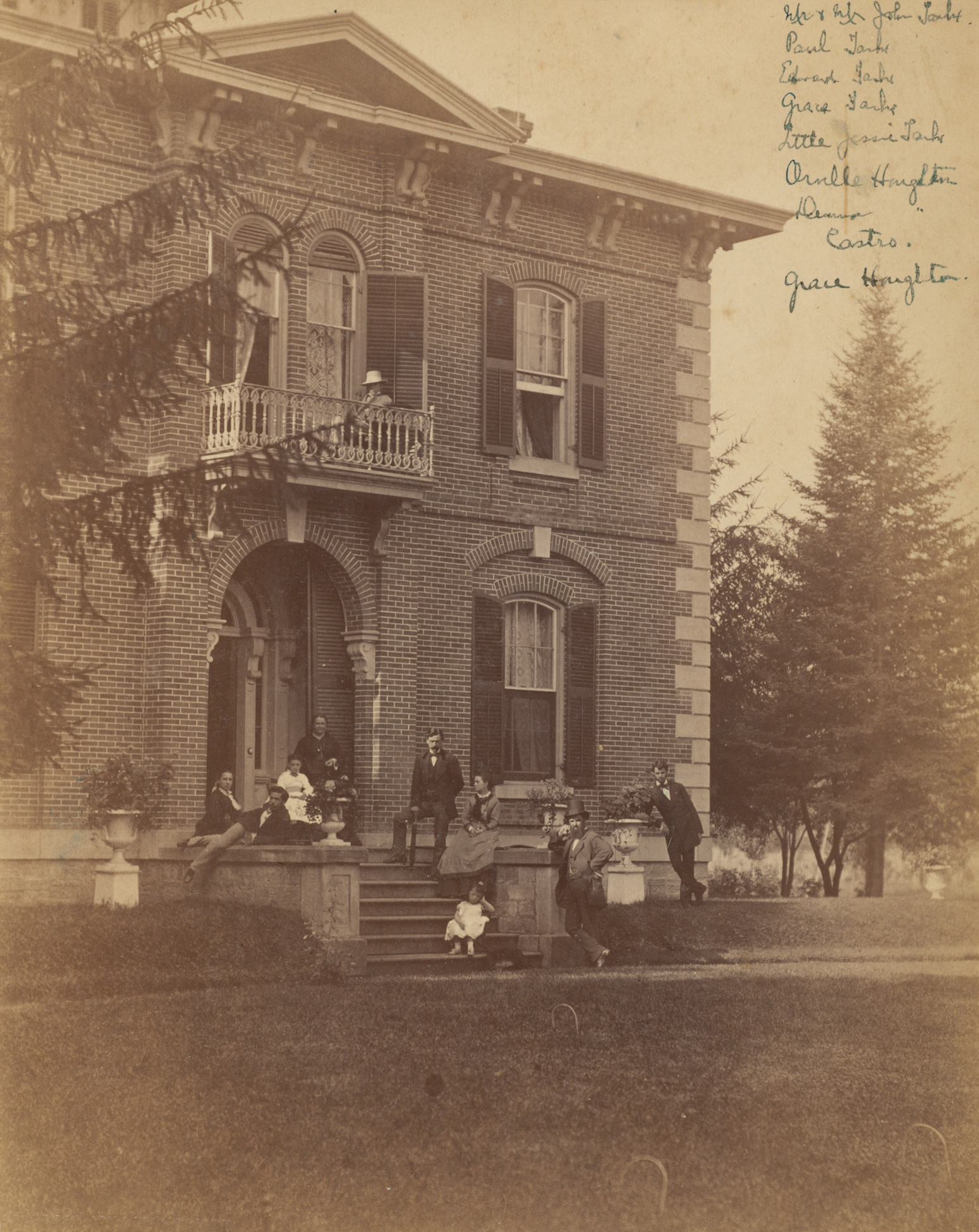

Margaret Watkins was born in Hamilton, Ontario, on November 8, 1884, to Marion (Marie) Watt Anderson, from Glasgow, and Frederick William Watkins, Jr., a Hamiltonian of Scottish-Irish descent who owned a large department store. She grew up in a large house on King Street East, just outside the city’s boundary—her father named the house “Clydevia,” after the Scottish river that Frederick and Marie travelled as newlyweds on their way to Canada in 1877. Christened Meta Gladys, she changed her name to Margaret when she left Hamilton in 1908 to live as an independent woman.

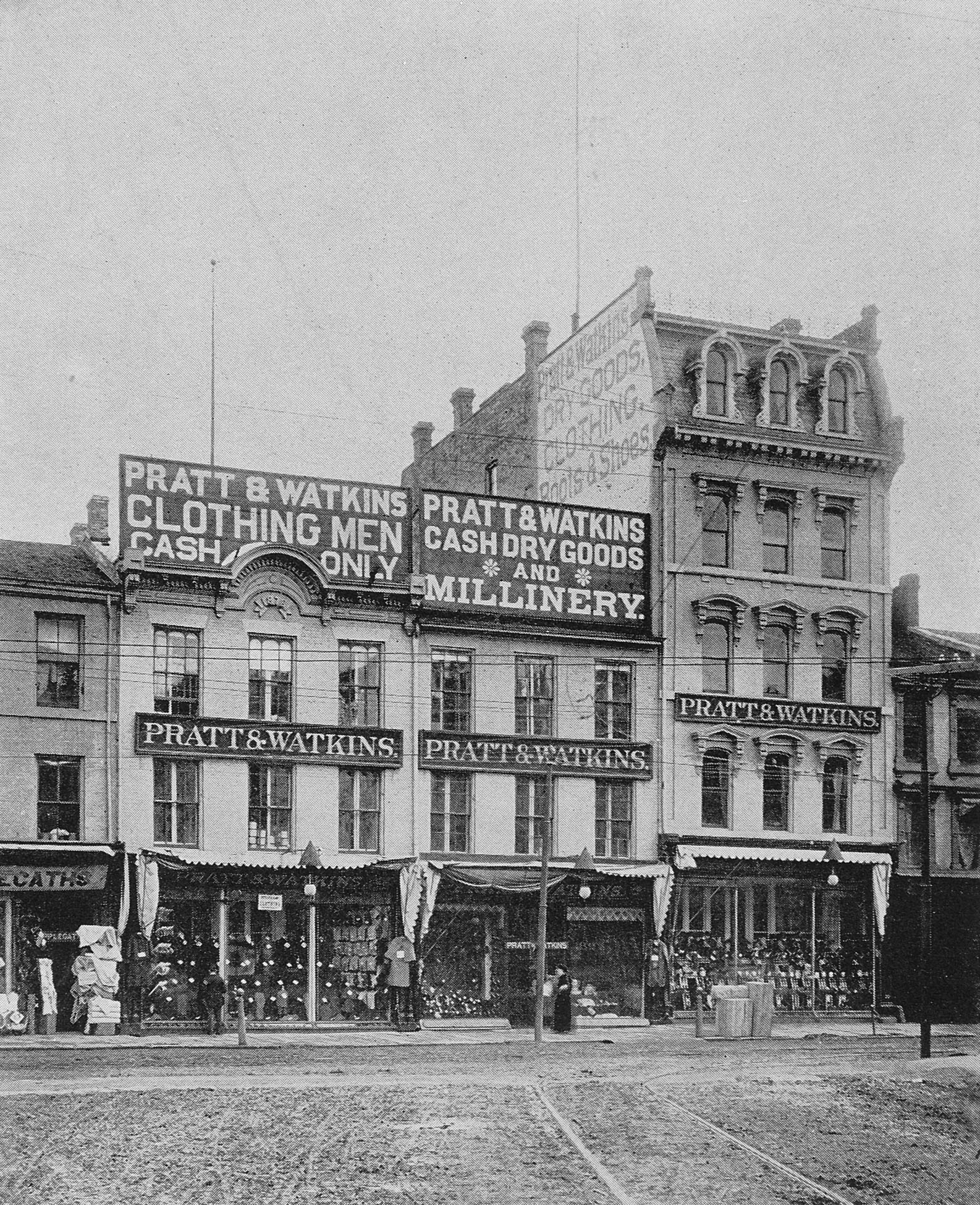

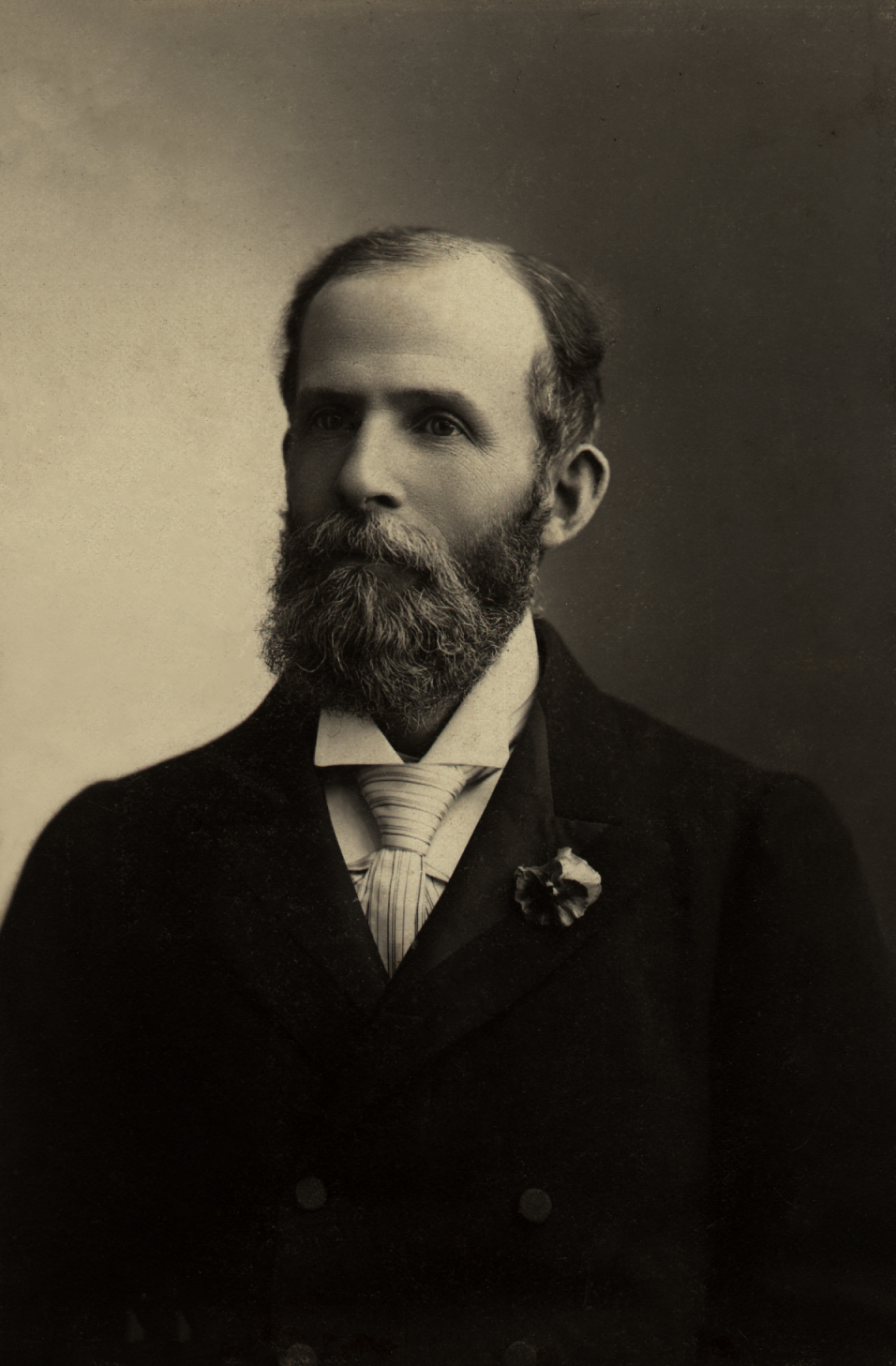

Letters exchanged by family members in Hamilton and Glasgow describe evenings spent looking at art books and photographic albums, whether the Masterpieces of Rembrandt or photographs from Egypt. The family also made trips to Europe and visited museums, so Watkins was fully educated in the art of the Renaissance and beyond. Watkins’s mother was one of the founding members of the Hamilton Branch of the Women’s Art Association of Canada, and her aunts living in Scotland created and sold painted boxes and bent-ironwork fire screens in Glasgow and Toronto. Watkins’s father also had a keen interest in art. He was an examiner at the Hamilton Art School, besides being a very public figure in an ambitious city known for its heavy industry and manufacturing. He was an alderman, an elder in the Centenary Methodist Church, a Temperance advocate, and even a candidate for federal Parliament (although he was unsuccessful in his bid). For the grand opening of his new department store in 1899, Frederick showed a motion picture depicting Christ’s death and resurrection (Passion Play of Ober-Ammergau) for five days to a reported 20,000 people. So, indeed, Watkins was brought up on pictures.

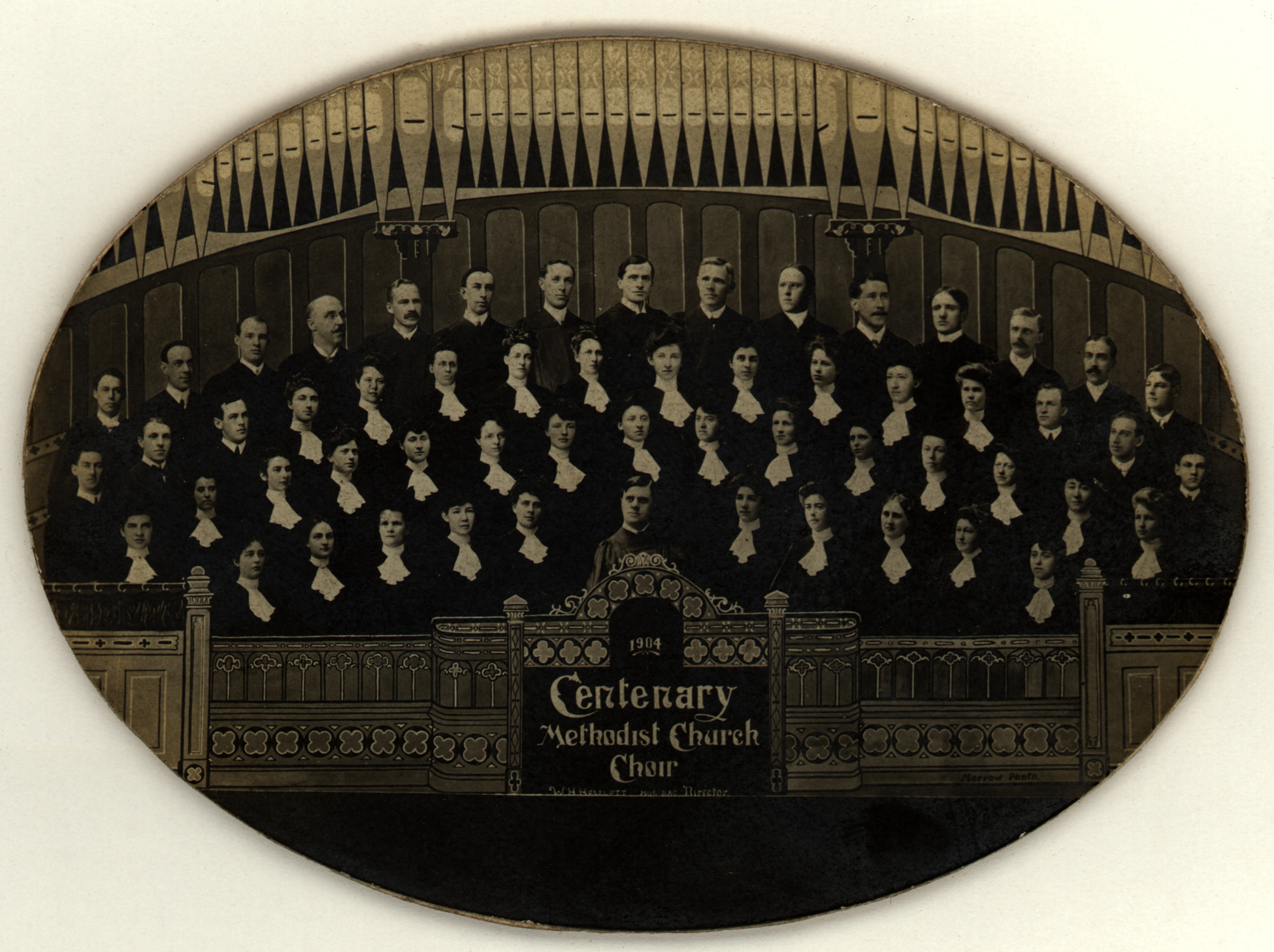

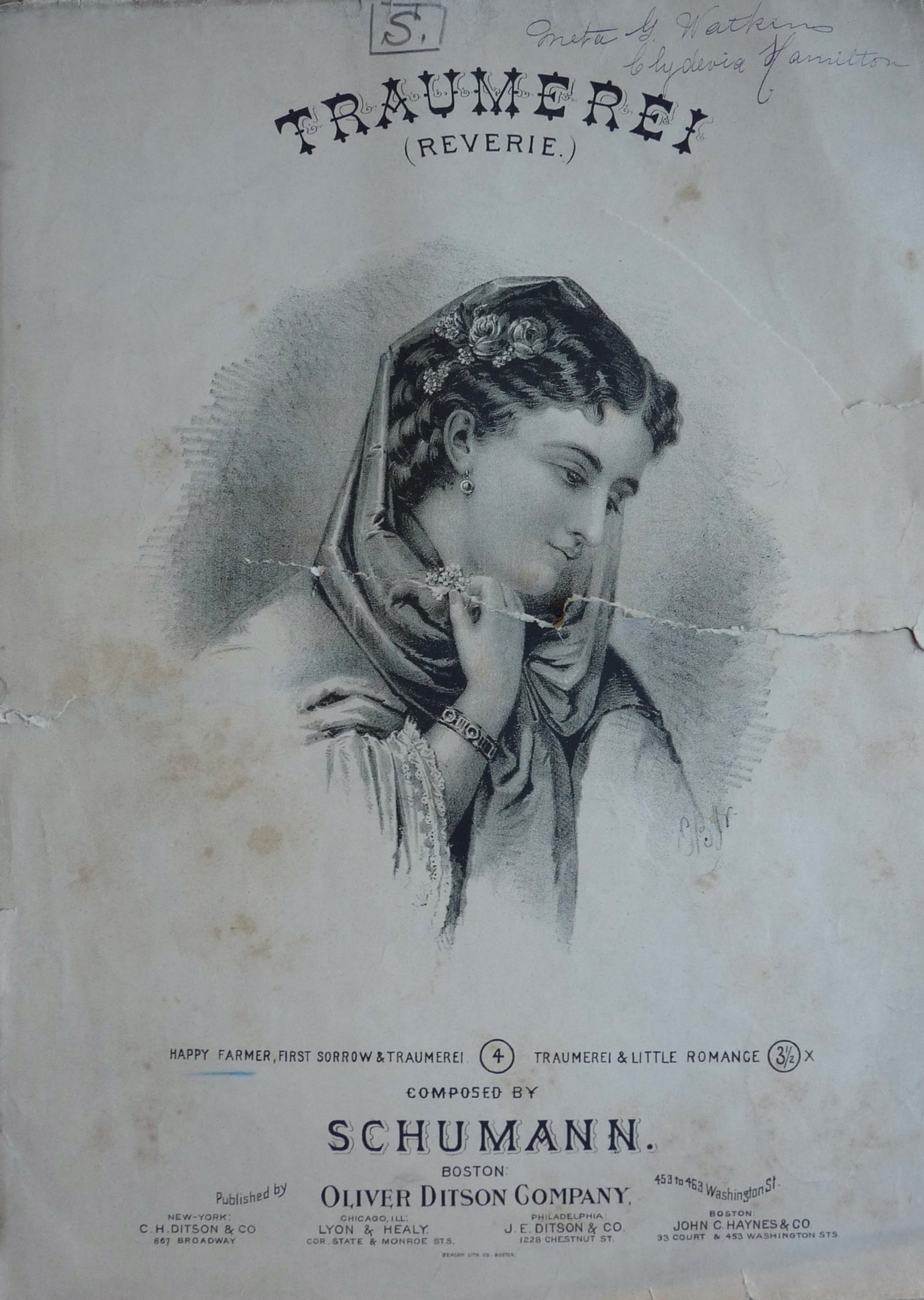

And music also filled her early life. As a child, she practised piano for four hours a day. As a young adult in Hamilton, she was known for her music skills, as part of a duet club, and singing, sometimes as the soloist, with the Centenary Methodist Church choir. Her tastes were varied, playing Mozart and Schumann, as well as Palestrina and Wagner. Watkins had a deep knowledge of and life-long attachment to music, and later described the art of photography as “the varying pattern of a fugue.”

Letters between her mother and aunts describe the women’s world of Watkins’s home. The domestic art of making the house and its objects beautiful remained with Watkins. In her adult life, she would find a new visual language to represent domestic objects, while rejecting traditional constraints for women.

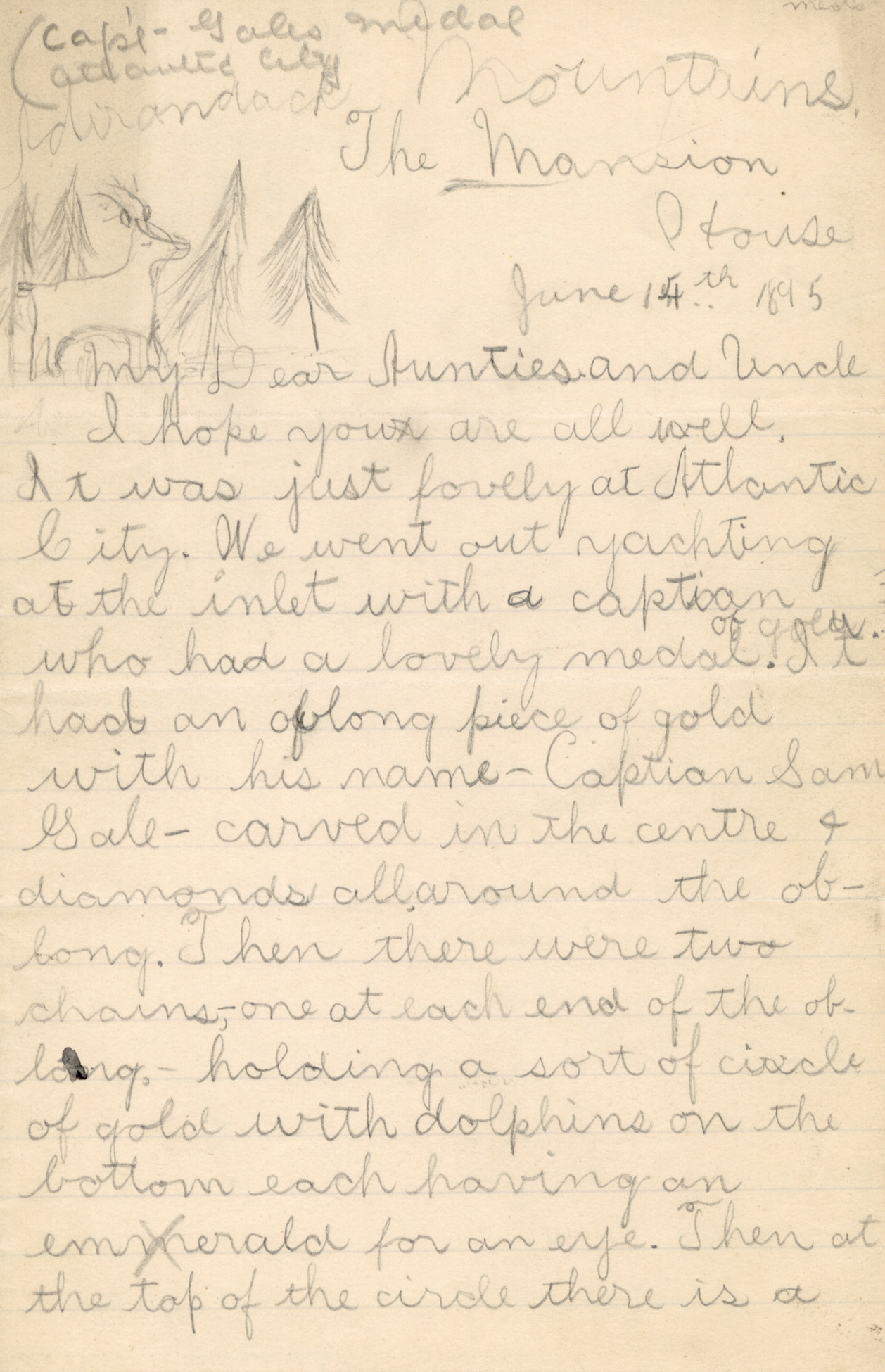

The young Watkins was trained to observe. At age ten, she wrote twenty-six lines in a letter to her aunts and uncle describing a gold medal she had seen and its shapes, gems, and figures. The detail reveals her interest in beautiful things, her observational skills, and her ability and desire to document it all. Her best grades in school were for drawing, though only one drawing remains (a sketch of her cousin Lily Roper). By fifteen, she had published a poem in the local newspaper and would continue to work on her poetry. From childhood on, Watkins saw herself as an artist.

So Watkins enjoyed a privileged, bourgeois childhood; at least, until she was thirteen. That year, on a family trip to Europe, her father had a serious bicycle accident for which he was subsequently treated at the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, an institution headed by John Harvey Kellogg that featured “many appliances, apparatus, [and] modern improvements.” Under the stress, Watkins’s mother had a serious nervous breakdown and was also sent to the Kellogg institution for a year. Margaret was left with her mother’s sister Louisa Anderson, one of the many fussy, strongly religious aunts who came to help. When Watkins’s father returned to Hamilton, he invested in the building of a 56,000 square foot department store and bought the most expensive residential property in Hamilton, as if overcompensating for the difficulty of the past year. Having converted to Kellogg’s Seventh-Day Adventism, he refused to open the store on Saturdays, and, within a year, Frederick Watkins was bankrupt. Clydevia was lost, and Watkins moved out of her privileged class.

Her father’s newfound fanaticism and the trite moralism of her aunts drove Watkins away from organized religion for the rest of her life. The bankruptcy also pushed her into adulthood. At fifteen, she was taken out of school to learn the domestic chores of cooking, cleaning, and sewing, but she also took it upon herself to earn money for the family by making objects to sell, ironically at the very store her father had just lost. Granted, these objects were pen-wipers and pudding tidies, but the industriousness began and never left her. She would be an artist who worked for a living, and the craft of printing photographs would later appeal to her love of handmade objects. Furthermore, Watkins created her most original work by reshaping domestic objects in her photography. The trouble was she did not know what medium to choose. In a draft poem written in her early twenties, Watkins exclaimed: “Oh damn you, Versatility!… There are so many hills to climb; / There’s Music, Painting, Vagrant Rhyme.” Her father’s uncle Thomas C. Watkins was an active member of the Hamilton Camera Club, but the families were not close, and there is no record of Watkins taking photographs until 1913. It would take six years of wandering to find her proper medium in photography.

Wandering, 1908–15

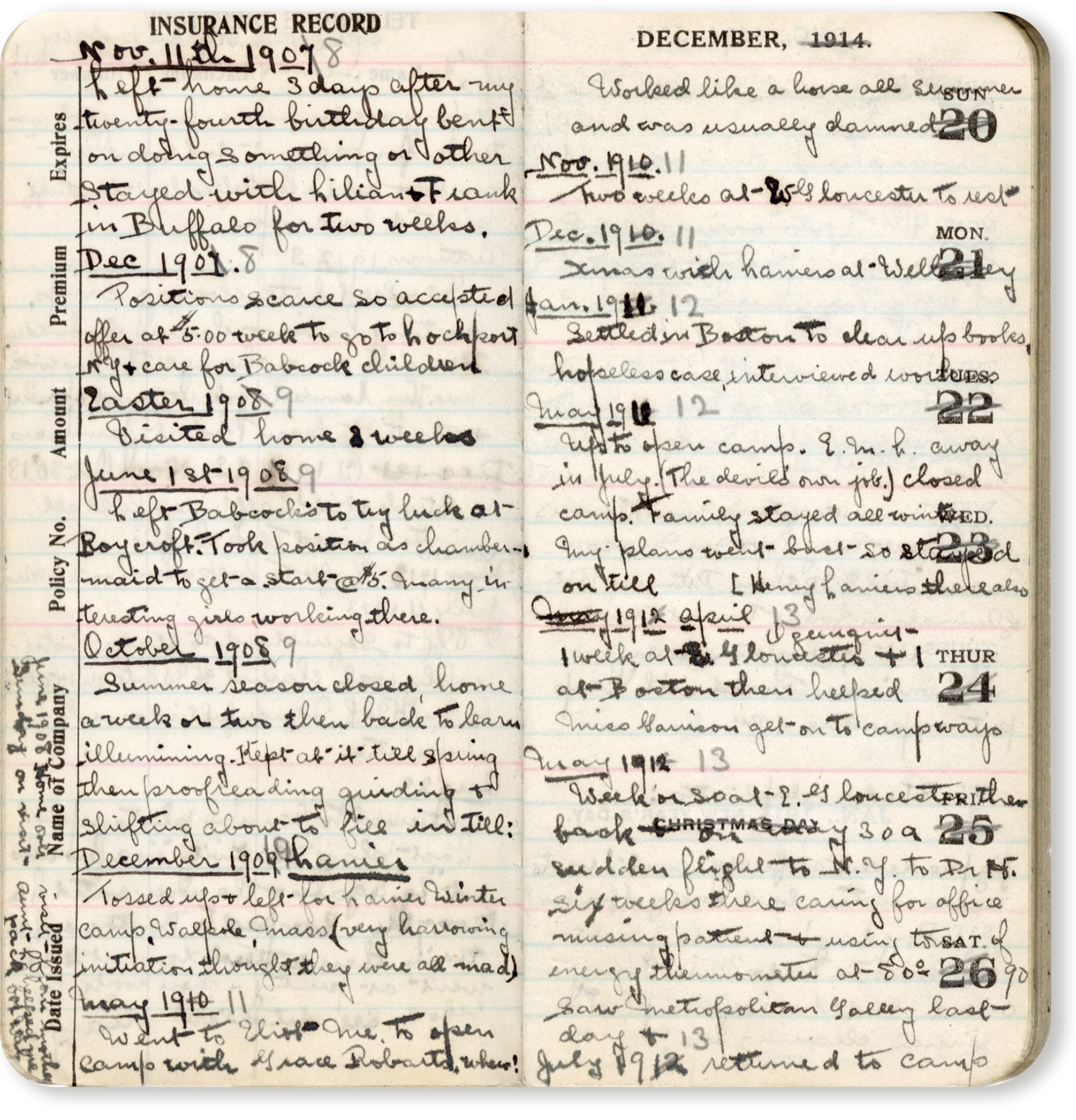

In November 1908, at age twenty-four, Watkins left home “to build a life & make a living.” Escaping the religious fanaticism of her family and feeling “domesticated to death,” she travelled across the border to the Buffalo area in New York, searching for an artist’s life. She joined the Roycroft Arts and Crafts company in East Aurora, an enterprise founded in 1895 by Elbert Hubbard as a place where the new styles of art and design from Europe were inspiring the creation of beautiful artistic and practical objects. Watkins entered through the back door as a chambermaid at $5 a week, but soon moved into making art in this large organization that employed, in her time in 1909, over 900 women. In a mostly gendered workplace, run as much as a factory as a “community,” Watkins noted meeting “many interesting girls.” New possibilities opened up as she imagined what a woman could do in the world. An unpublished essay on the French painter Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899), drafted by Watkins while at Roycroft, shows Watkins’s growing feminist consciousness, particularly her understanding of what it meant to be an independent woman artist. (Bonheur was known for strong representations of large animals that she viewed in Paris abattoirs.) At Roycroft, Watkins illuminated books, did proofreading and guiding, and gave concerts in the hall. On leaving a year later, she took with her a love of beautifully designed books and household items. Her Roycroft copper plate found its way into many of her kitchen still-life photographs, such as Still Life – Circles, 1919.

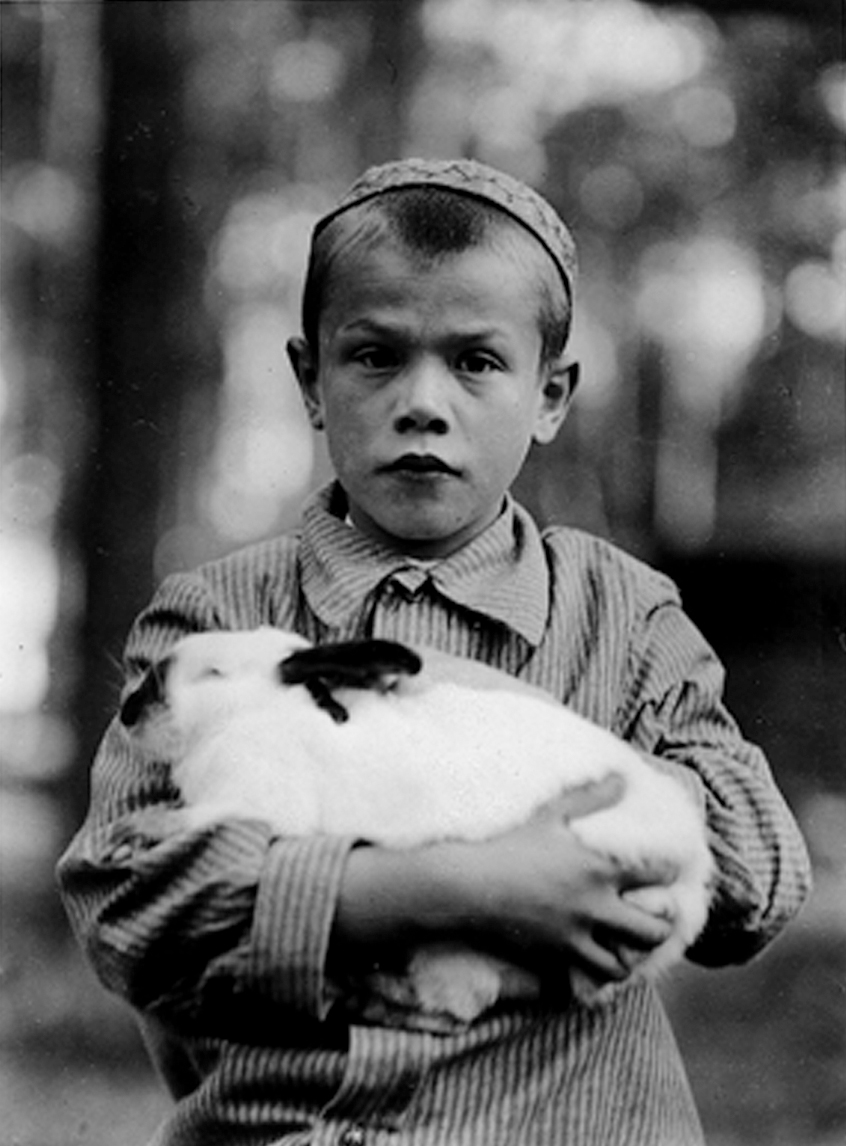

In 1910, Watkins moved to another Arts and Crafts community: the Lanier Camp, which operated in the winter and summer and was located in Massachusetts and Maine, respectively. It was run by Sidney Lanier, Jr. (the son of the Southern romantic poet Sidney Lanier), whose attachment to nature and manual labour was informed by the philosophies of writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. The camp was known for the artistic work it offered both children and adults, notably various crafts and a series of Bible plays they put on in the surrounding pine forest. When Watkins arrived, according to her diary and personal writings, she “thought they were all mad,” but she built strong attachments to those who worked there. She took on odd jobs from crafts and costume design to carpentry. “This summer,” she wrote in a note around 1912, being “’artistic’… meant that I could take the crown of an old hat, a portiere, a mattress cover, a dyed remnant of cotton, a bit of velvet, & an East Indian mat[,] drape them over a suit of pyjamas & achieve a result (somewhat) like [a] Pharaoh.” Although Watkins left Lanier Camp in the autumn of 1913 and took up a job that allowed her to learn photography in Boston, she returned for the subsequent four summers to apply her burgeoning photographic skills and creative abilities. She eventually became its official photographer, documenting their activity for promotional brochures and book-length publications, as well as portraits.

Watkins took up photography as a profession for the first time in 1913. It was a year of changes. She had been helping Henry Wysham Lanier (Sidney’s brother and author of many books, including Photographing the Civil War) and his wife with photographing camp activities, but left camp in the spring to work in New York City for six weeks, helping a “Dr. H” with his practice and tending to his patients, and visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She then settled in Boston and took up an apprenticeship with Arthur L. Jamieson, a photographer who had studied with Léopold-Émile Reutlinger (1863–1937), a Parisian portrait photographer of celebrities such as Colette and Sarah Bernhardt. Jamieson was introduced in the pages of Photo-Era Magazine as “a conscientious, painstaking artist” whose forte was “charming vignetted portraits of women and children.” Watkins helped both Jamieson and his wife with sittings, developing, printing, and mounting.

With minimal income, Watkins lived in the attic of a friend’s house in Boston and kept up her music and poetry. She joined a Reform synagogue choir at the Temple Israel, with concert performances as well as religious services. Her milieu of artists was for the most part socialist, feminist, and anti-war. Her unpublished poems of the time address workers’ troubles and the cost of war on the lives of women. Despite her constrained financial circumstances, these years were busy with social and cultural events—concerts, theatre, films, and restaurants. By 1915, she had made enough of an impression in her circle of acquaintances to be invited to debate “The Relations of Art to Democracy” in an essay for the Boston Sunday Globe. The other debaters were the art critic Mason Green, and the well-known socialist Horace Traubel, friend of photographer Clarence H. White (1871–1925) and biographer of poet Walt Whitman. Watkins argued that art resides in the everyday and in everyone. For Watkins, the artistic spirit was everywhere: in poor shop girls who gave up a meal to sit in the top back row of the opera house, in the girl living in a garret writing essays (a reference perhaps to her own living conditions), and in the ironwork of your kitchen stove covered in splashes of soup. Her words look back to her childhood of arts and crafts, to her current penury living in an attic, and to her future brilliant photographs of kitchen objects, such as Untitled [Kitchen, Still Life], 1921.

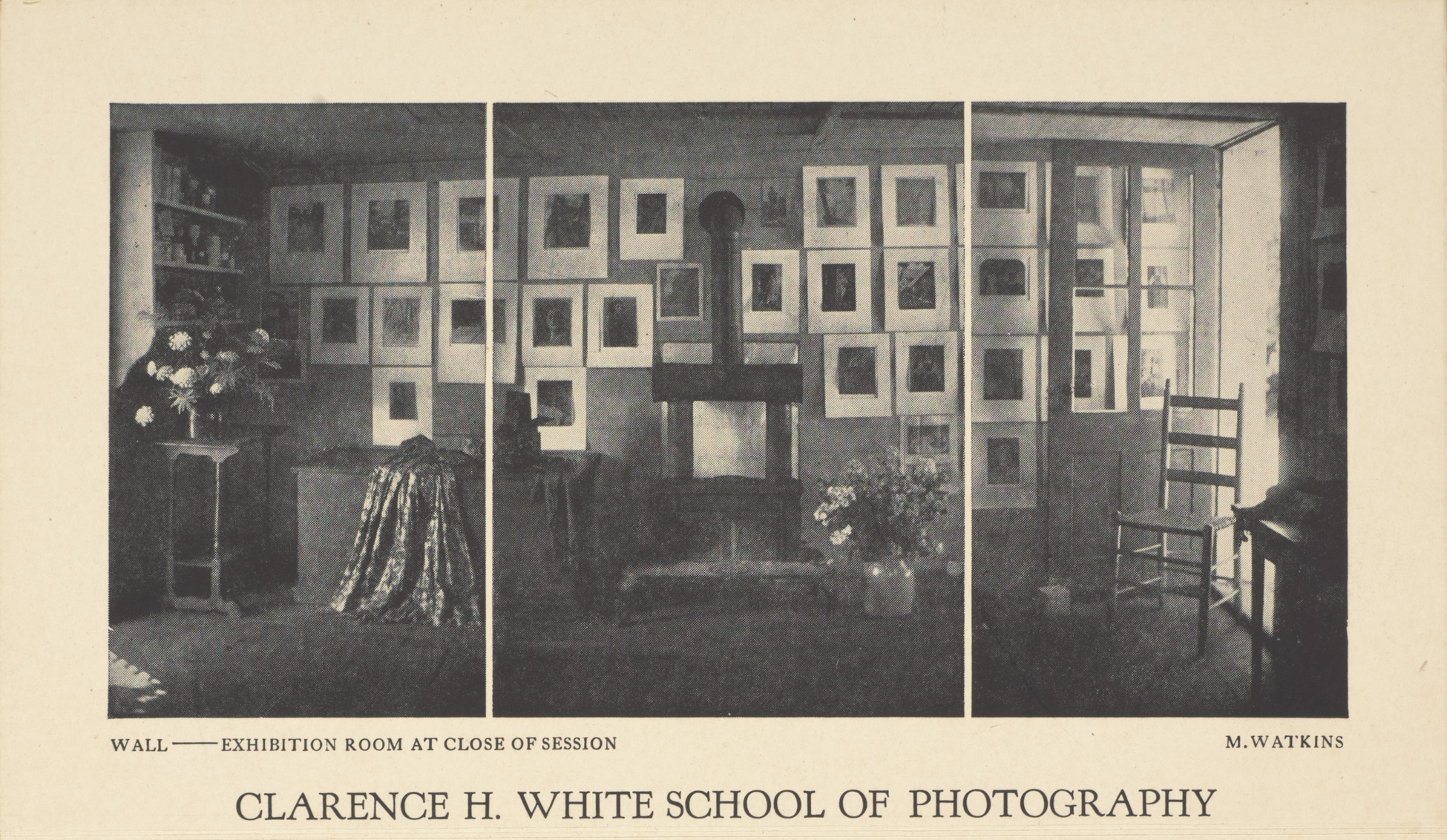

During the summer of 1914, Henry Wysham Lanier lent Watkins the money to attend Clarence H. White’s Seguinland School of Photography in Maine for six weeks. And there her life as an artistic photographer began. She had a technical base from Jamieson, but the summer school introduced her to major Pictorialist photographers of the time, such as F. Holland Day (1864–1933) and Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934), who were invited to the summer school to give feedback and advice to students. Their Pictorialist photography employed the compositional and tonal strategies of paintings, sometimes even its traditional subject matter, as in Käsebier’s The Manger, 1899. On the other hand, a major influence that summer was the Cubist painter Max Weber (1881–1961), who taught a course on composition for the school. While the art of the Old Masters had always inspired art photographers, many of whom, such as Käsebier and Edward Steichen (1879–1973), trained first as painters, Weber had studied painting in Paris and brought the modern techniques of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) to New York. At the school, he translated the principles of painting into the making of photographs, emphasizing the two-dimensional character of both forms. So, as she was deepening her knowledge of Pictorialist printing processes, Watkins was also learning about modern abstract compositions. On the one hand, she could produce a soft-focus, ethereal Pictorialist image of sunlight in a girl’s hair, as in her portrait of Henry Lanier’s daughter, Josephine; and on the other, she could create a composition whose sole organizational principle was its multiple angles or its dark centre, as in Untitled [Bridge posts in water, Maine], 1914.

With her new success at the White school and the connections she made there, Watkins was ready to dedicate herself to a career as a photographer. She would always need to earn an income through her photography, either with commissioned portraits, illustrations, or advertising photography, but she was committed to making works of art. A year later she moved to New York City, and her searching for the right medium, as well as her days of wandering, were over.

New York City, 1915–28

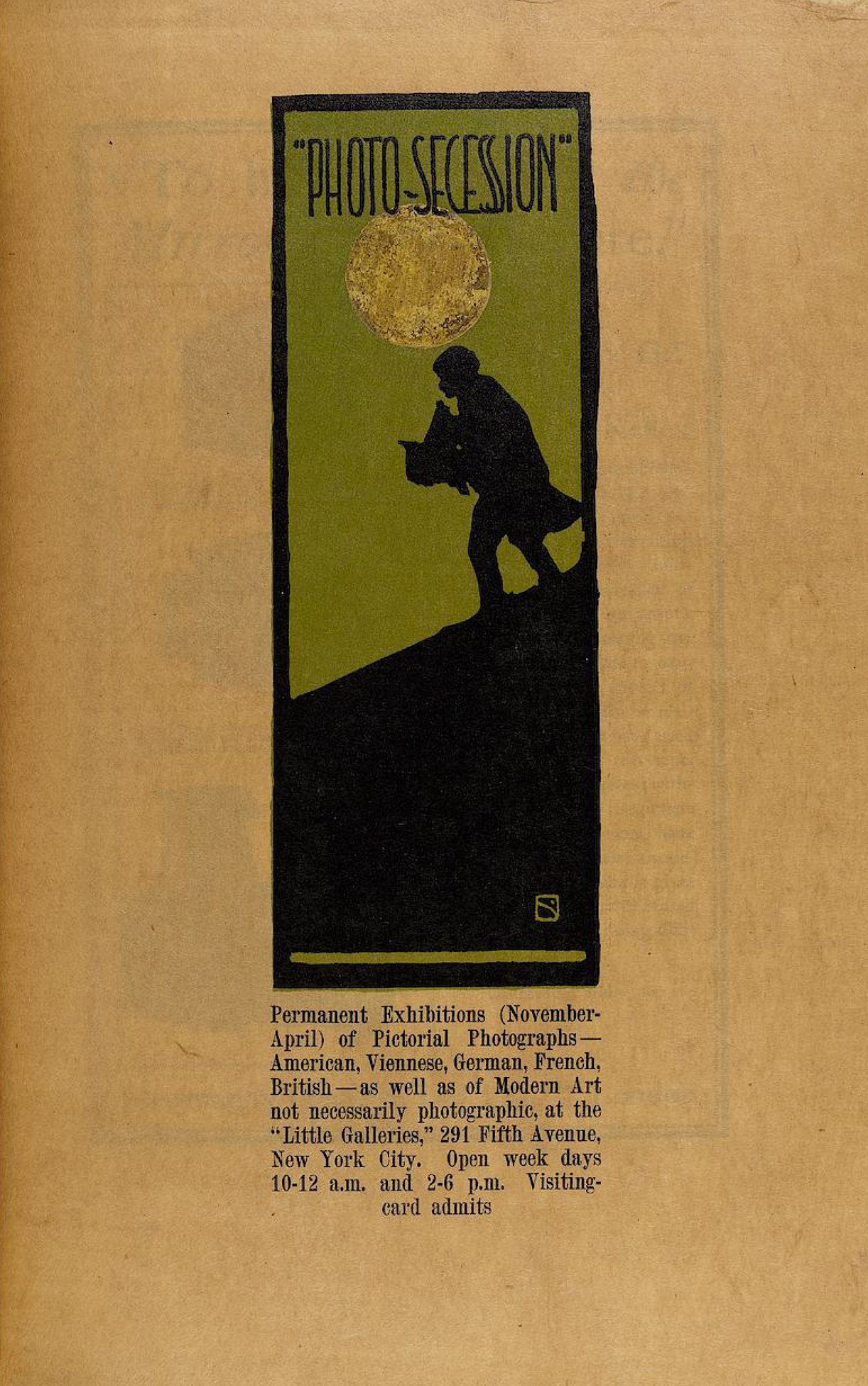

Watkins moved to New York City on October 15, 1915. Hired by Alice Boughton (1866–1943) at $10 a week as an assistant in her portrait studio on East 23rd Street, Watkins entered an exciting world of art and photography, which she in turn began to shape. Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) had been fighting against the amateur and professional photography practised in camera clubs throughout America, which saw the medium primarily as a mechanical and scientific way to produce a document of the material world, with art photographs often limited to quaint depictions of landscapes and portraits. He and others struggled to have photography recognized as an art form on par with painting, sculpture, and traditional print-making. While Pictorialist photographers explored the artistic possibilities of photography by imitating the techniques of painting, Stieglitz founded the Photo-Secession, a break-away group that included Boughton, Clarence H. White, and Gertrude Käsebier, promising an art of original expression.

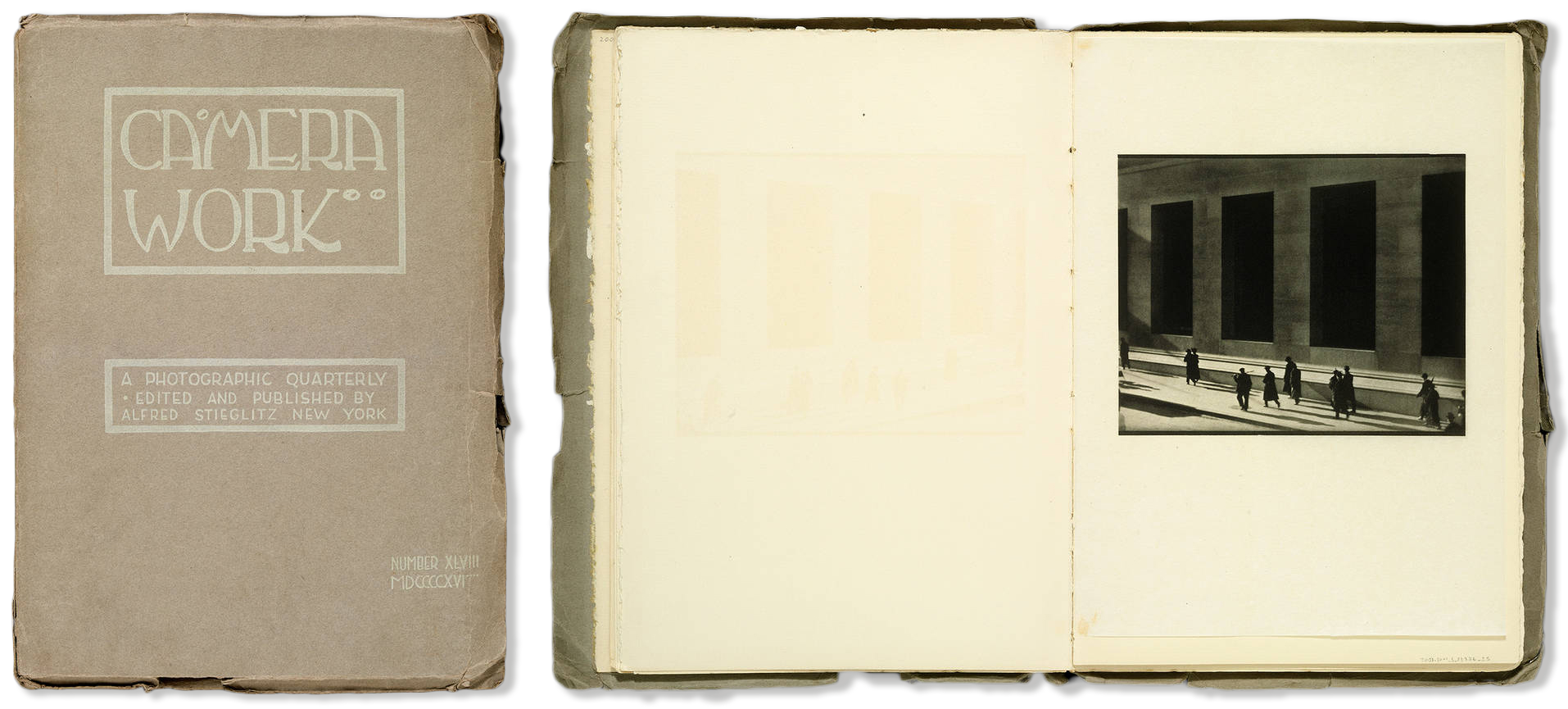

Stieglitz’s periodical, Camera Work (1903–1917), and the exhibitions he organized as early as 1902 and continued at his Little Galleries advanced the cause of a new photography. In 1915, White claimed the term “Old Masters” for photography, thus equating it with the acknowledged art form of painting. He mounted an exhibition that included photographic prints by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879), Lewis Carroll (1832–1898), and David Octavius Hill (1802–1870), now considered the pioneers of art photography. Ultimately, the first museum to accept photography as art into its collection was the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1928, when it accepted Stieglitz’s collection of Photo-Secession prints.

The networking out of the Clarence White school led to Watkins’s first job in New York in 1914. White himself would eventually hire her to teach at his school, but he and other photographers connected with the school would have recommended Watkins to Alice Boughton. White, Käsebier, and Boughton were part of the 1910 break-off group from Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession. A new group met regularly in Mitchell Kennerley’s bookstore in New York City, and Max Weber conducted photo critiques to White’s students there. Watkins had stepped into an active photography milieu, and her original work meant that she would thrive within it.

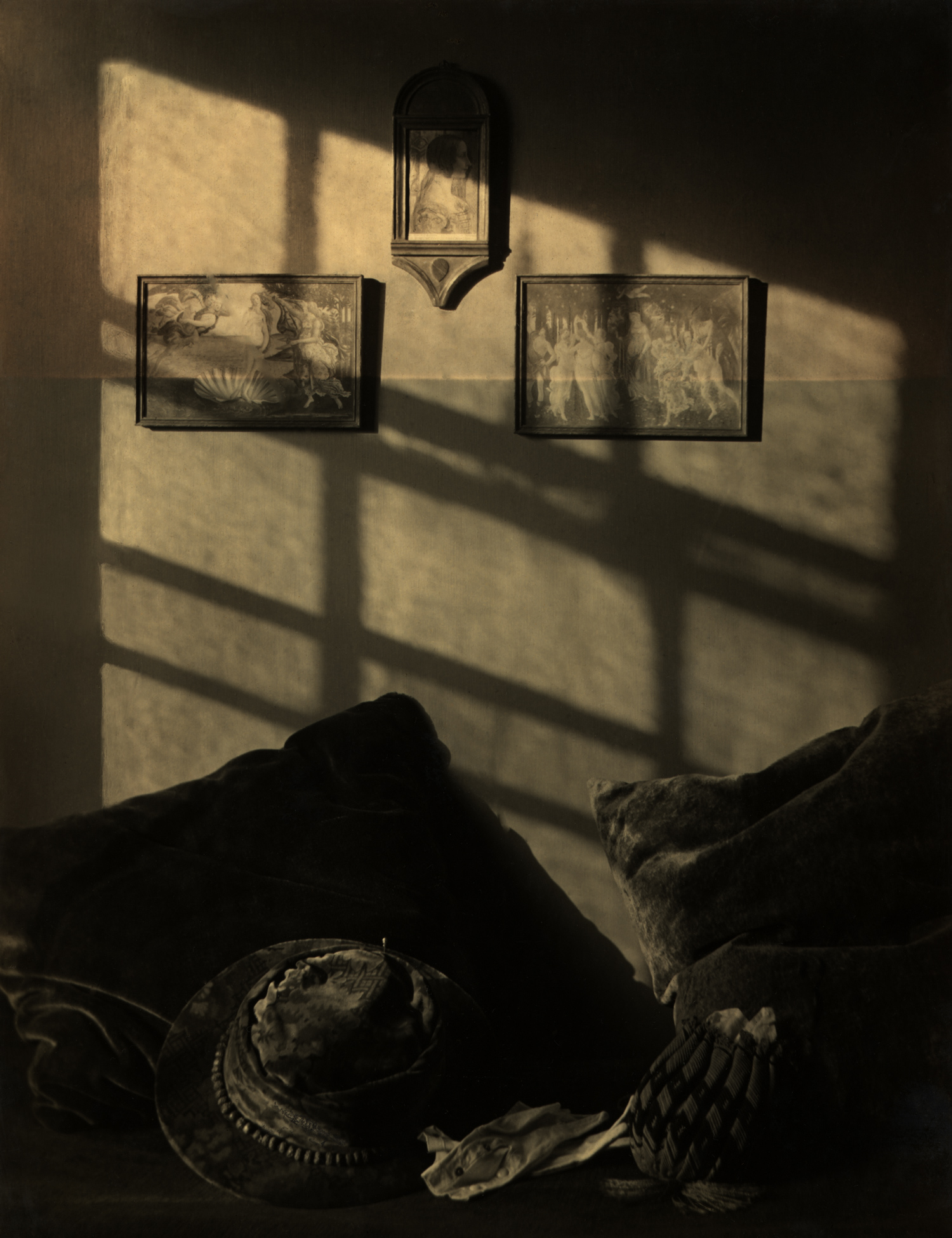

Boughton’s studio was known for photographing celebrities in the world of art, music, and literature, including Henry James and W.B. Yeats. Watkins’s diary records helping with the sittings of Russian writer Maxim Gorky, British poet Laurence Housman, and French singer and dancer Yvette Guilbert, among others. Watkins also attended the Saturday get-togethers in the studio with other artists, including critic and poet Sadakichi Hartmann (1867–1944), and photographers Käsebier and Edward R. Dickson (1885–1975). Dickson and Watkins worked on their own images in Boughton’s studio, paying for their supplies. Watkins brought to the studio her previously acquired technical expertise in developing, printing, and mounting photographs. She admitted to a fastidious approach that she referred to as her “fussing,” but she learned from Boughton’s portrait strategies, often imitating fifteenth- to eighteenth-century paintings using period costumes and chiaroscuro lighting, such as Petrus Christus’s Portrait of a Female Donor, c.1455, as in her own The Princess, 1921.

On first arriving in New York, Watkins boarded at The Shirley on West 21st Street, a woman’s residence, but in 1916 her cousin Sarah Hutchinson died, leaving her an inheritance of $3,000 (the equivalent of $82,000 today). Finally, Watkins could afford to rent “a room of one’s own” (what British modernist writer Virginia Woolf argued was necessary for a woman to produce art). A garden flat at 46 Jane Street in Greenwich Village became Watkins’s home and studio. She described it in letters:

“Home sweet home” wasn’t always that to me, and for the first ten years on my own I perched in rented hall bedrooms or odd corners of other people’s houses. So that to have bedroom, bath and living room (with a discreet “kitchen corner”), to haunt junk shops and old furniture shops, and to pull the whole thing together—well I had the time of my life.

In this apartment, Watkins found her distinct voice. That singular perspective is encapsulated by her description of a cabinet in her living room:

All old china in the top…. Desk part holds all chemicals and retouching materials; top drawer portfolios of prints all labelled and in shape to show people; middle drawer portfolios of pictures, engravings, colored prints and copies of Old Masters which we trot out and study every little while when we want amusement; and bottom drawer, (the largest) is jammed full of mending and sewing materials, to be handy when there is time to spare!

This is a “making do” with what is at hand, an inventing out of the world she inhabited, a world in which she could be an artist on her own terms and in her own space. For instance, she could cherish the Chinese screens she had found in a local antique store, hang them on her wall as decoration, and then ingeniously deploy them as a structural framing device for a portrait, as in Untitled [Portrait of a Man], 1924, as easily as one for a nude, as in Tower of Ivory, 1924.

The metropolis gave Watkins work, friends, art, and a bustling life filled with exhibitions, movies, concerts, plays, and restaurants. She might have lunch at the Cosmopolitan Club (a private woman’s club) and attend a concert by African American singer and activist Paul Robeson in the evening. She worked too hard, suffered headaches, even fainted in the street on one occasion, but she was becoming a recognized photographic artist. Her cousin Arthur Watkins Crisp (1881–1974) had left Hamilton for the Art Students League and had a career as a notable muralist in New York. One of Watkins’s early commissions in 1918 was to photograph at the Greenwich Settlement House where Crisp had painted murals.

Watkins produced perhaps her most iconic photographs in 1919: The Kitchen Sink, Domestic Symphony, Still Life – Shower Hose, Design – Curves, and Still Life – Circles. White asked his students to find their subjects in the everyday. Watkins took her camera into the intimate spaces in her Greenwich Village apartment, isolating everyday objects. While other photographers were pioneering from the top of skyscrapers or out of airplanes, Watkins was revolutionizing our way of seeing dirty dishes.

Her productivity during this year is due in large part to the fact that Watkins had left her job with Boughton and taken up employment at White’s photography school in New York City. While working at the school, she, at various times, taught photography, was registrar, co-ran the summer school, and eventually was White’s personal assistant. She was known at the school as an exacting teacher with technical expertise—a “tough dame” who could sort out your developing or printing problems. She also passed on her innovative modernist composition of domestic still-life photography, influencing a new generation of American photographers that included Ralph Steiner (1899–1986) and Paul Outerbridge, Jr. (1896–1958).

Watkins was an outgoing person who gave herself completely to the friends and organizations she was attached to. Her life in New York City encompassed a network of different communities, which in turn provided her with opportunities for photographic commissions and the circulation of her art. Her involvement with White’s school saw her not only teaching, but also organizing exhibitions for his alumni. She herself exhibited first with the school in 1917. In 1920, she had her first international exposure in the Copenhagen Amateur Club in Denmark as part of a group selected by the Pictorial Photographers of America (PPA), on whose executive she also served along with White.

An Artist in Demand, 1921–28

Watkins had a quick rise to prominence. In 1921, she was featured in a full-page spread in Vanity Fair (a trendsetter magazine of the twenties, publishing the latest in art and writing); her work was compared to the sculpture of Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) and the paintings of Pablo Picasso. In the same year, Watkins won first prize for Still Life – Circles, 1919, at a PPA exhibition at the Art Center in New York. The Art Center brought together seven artists’ associations, including illustrators, photographers, and art directors (for magazines and advertising agencies). As such, it provided an excellent venue for networking and commissions.

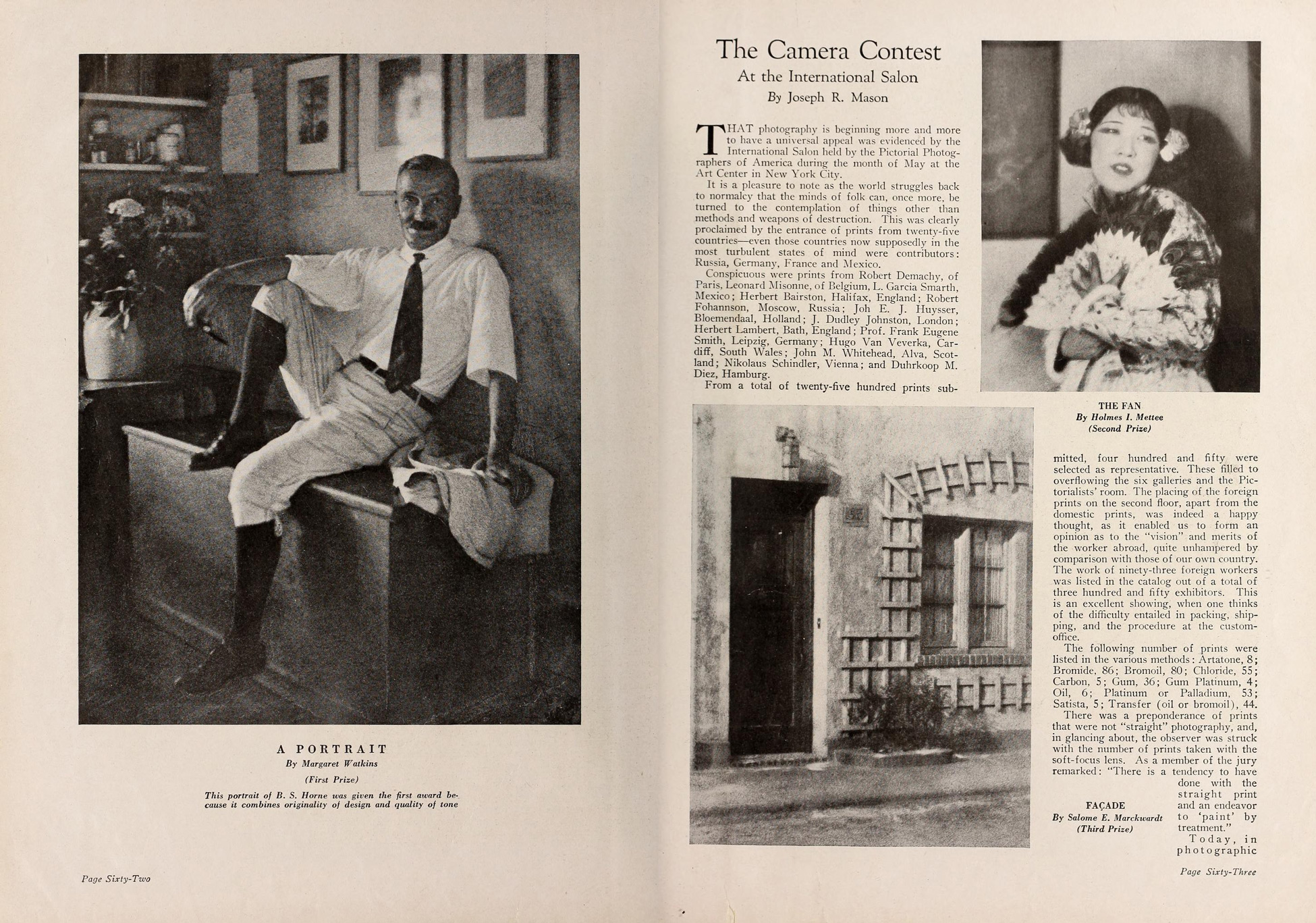

Publications and exhibitions increased her exposure. Watkins published her work in art or photography journals such as Shadowland, Camera Pictures, and Ground-Glass, as well as in the PPA annual photography book. She appeared three times in 1923, winning prizes for A Study in Circles, 1921; The Bathroom Window [Sun Pattern], 1919; and A Portrait [Bernard S. Horne], 1921. Between 1920 and 1925, Watkins appeared in twenty-one group shows in New York, British Columbia, California, Japan, and Java, winning seven prizes and selling The Bathroom Window [Sun Pattern], 1919, at the International Kohakai Salon of Photography in Kobe. She also followed White onto the executive of the Art Center. As a culmination of her success, the Art Center offered Watkins a solo show in 1923.

After this show and her exposure in Shadowland and Camera Pictures, Watkins’s work was in demand: art directors from the high-end department store Macy’s, advertising firms such as J.W. Thompson, and other ad agencies began to request still-life studies for their products. The Art Center housed not only the PPA, but also the Art Directors’ Club, presided over by Heyworth Campbell, a friend of White who also served as a creative director at media empire Condé Nast. Watkins’s connections with the Art Directors’ Club helped her own career. She had discovered a way to isolate domestic objects not in a stark or mechanical way but by using elements of design and mystery to entice viewers, as in Domestic Symphony,1919.

The shift from art illustration to photographic representation in advertising imagery was just beginning. The first advertising work by photographer Edward Steichen, considered a pioneer in this field as well as a prominent art photographer, was published in September 1923; Watkins’s first advertising images appeared in February 1924. She understood that the principles of abstract art would sell products by enhancing them with “fine tone-spacing and the beauty of contrasted textures,” as shown in her glittering circles and light of glass, Art Deco lines of perfume bottles, and triangles of black and white on Modess boxes. In fact, Watkins, along with Steichen, was transforming Pictorialism into modernism.

Watkins also served in two women’s organizations at this time. In 1923, she became the official photographer for the New York Zonta Club, a networking group for professional and business women. She was also a member of the Canadian Business and Professional Women’s Club, which provided her a solo show in New York in 1924. Her Zonta Club connections brought her portrait commissions for notable figures in the art world, such as Katherine Dreier (1877–1952), a suffragette, painter, patron of the arts, and co-founder of the Society of Independent Artists, which built the first institutional collection of modern art in New York. With her friend Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), the Dadaist and innovator of Conceptual art, Dreier also founded the avant-garde association Société Anonyme. Their modernist influence can be found in Watkins’s portrait of another Zonta Club member, Nina B. Price, who was a successful publicist of the time.

In her portrait work, Watkins mainly photographed people from the arts world: dancers, artists, and musicians, perhaps the most famous being Russian composer and piano virtuoso Sergei Rachmaninov. Through friends working or studying at the Art Students League, she received commissions from painter Kenneth Hayes Miller (1876–1952) and muralist Ezra Winter (1886–1949), exhibiting the resulting works in her own solo show. Her friends and teachers at the White School offered themselves as models, including White himself and Bernard Shea Horne (1867–1933), with whom she co-ran the summer school. Her Canadian friends were also glad to model for her work, with Verna Skelton from Walkerton, Ontario, depicted as if in a Julia Margaret Cameron photograph of the Victorian era, or posed holding a tea cup for a Cutex nail polish advertisement.

In her own self-portrait, Watkins raises her head to look down on the viewer. This is not a meek woman. As she reportedly said of her photographs, “They are unusually interesting, sometimes beautiful—but never, I hope, ‘pretty.’” So when her self-portrait was published framed in an oval and touched up to suggest lipstick and mascara, she railed against being made to look like a “snake-eyed vamp.” She was an independent woman, not interested in using female charms or fitting into the stereotypes of demure maiden or seductive femme fatale. Rather, she was a “New Woman,” along with other empowered women of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, determined to challenge gender norms, live independently, and have a role in public life. Watkins joined others “making revolutionary changes in life and art.”

With the death of Clarence White in 1925, Margaret Watkins’s life significantly changed. Not only had she lost her friend, co-worker, and mentor, she lost her community at the school. White had set aside ten (sometimes identified as eight or twelve) of his prints for Watkins in lieu of payment for some of her work. After his death, Mrs. White sold those prints to the Library of Congress. When they were hung with the Clarence H. White Memorial Exhibition at the Art Center, Watkins had a bailiff confiscate them, and a court case ensued, where, through innuendo, it was implied that Watkins and White had been having an affair. She had been cast in the role of the snake-eyed vamp she had repudiated. Watkins lost the case. She was paid for the prints, but they remained with the Library of Congress.

For the next two years, Watkins continued working hard with the PPA and with commissions for advertising photographs. She received requests to show work in the United States and elsewhere and was invited to present her work and thoughts on design to the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, which in 1889 had started one of the first departments of photography in the country. But she was exhausted. Watkins planned a three-month holiday in Europe, and never returned. Home had been Jane Street and New York City, and she had lost it.

Glasgow and Europe, 1928–38

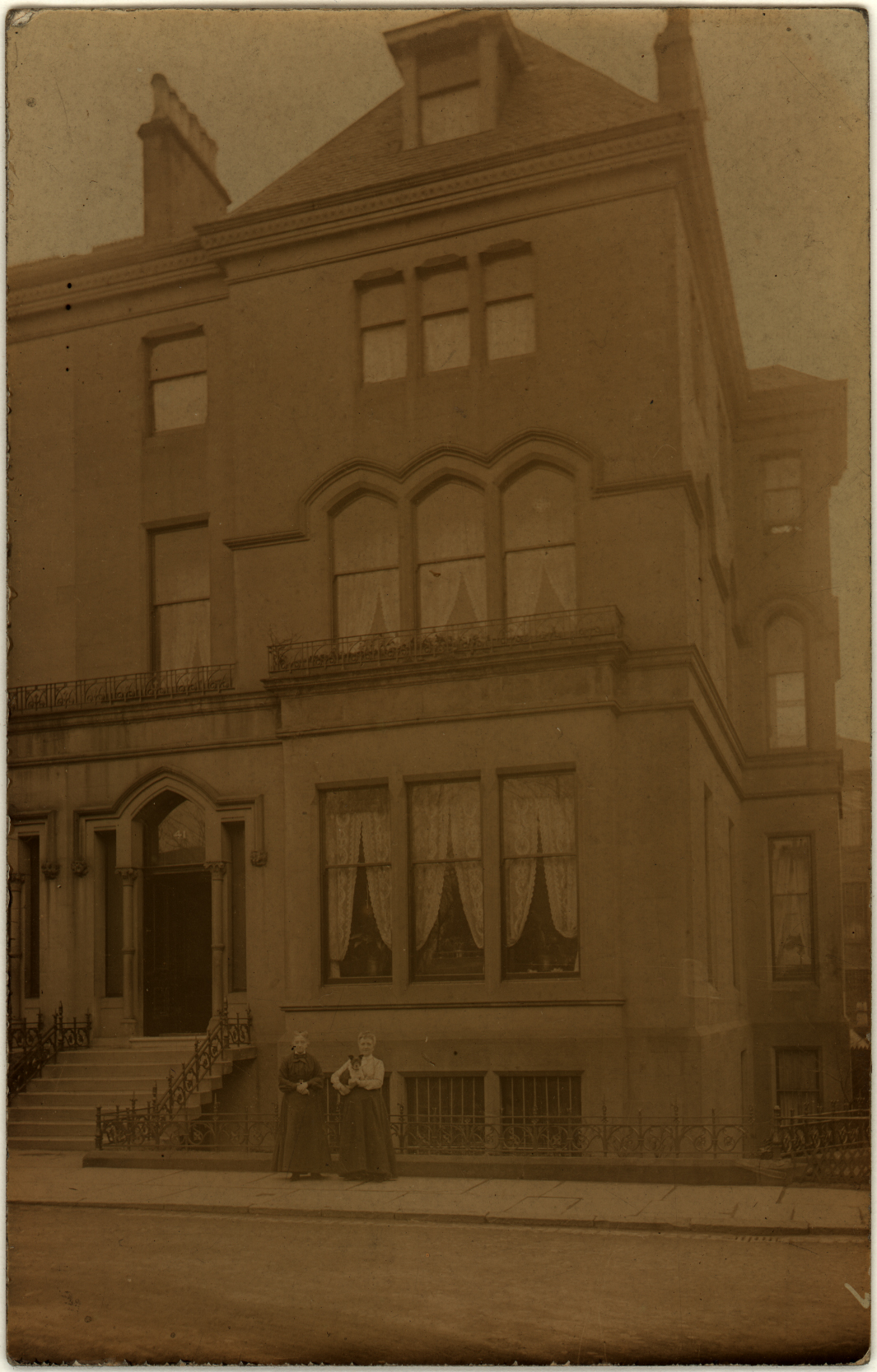

At the start of her European holiday in late August 1928, Watkins stopped in Glasgow to visit her aging maternal aunts at 41 Westbourne Gardens, only to be faced with the death of one within the week. The other three who still lived in the family home were in various states of debility. She wrote to friends: “The youngest(!) is 77 and has been in bed for five or six years; the next, 80, valiant but very tottery and subject to the most shocking insurrections in the interior; the eldest 86, a human dynamo, loves the movies, tries to manage the whole solar system and is furiously indignant if I suggest that she is perhaps not quite so strong as she was in the good old days.” (That “human dynamo” was Louisa, Watkins’s main childhood caregiver. Each unmarried aunt had spent time in Hamilton helping Watkins’s mother). They were hoarders with “stockings enough for a centipede.” Watkins raged: “If I see one more black beaded bodice I shall be carried out screaming!” This was the domestic trap Watkins fell into, as the only single woman in the family available to look after her elderly relatives, despite the fact that she was “not just exactly suited by temperament, or temper, to be the honorary curator of an old Ladies’ home! But there you are—needs must!” She moved in, reluctantly, to return the care she had received from them as a child.

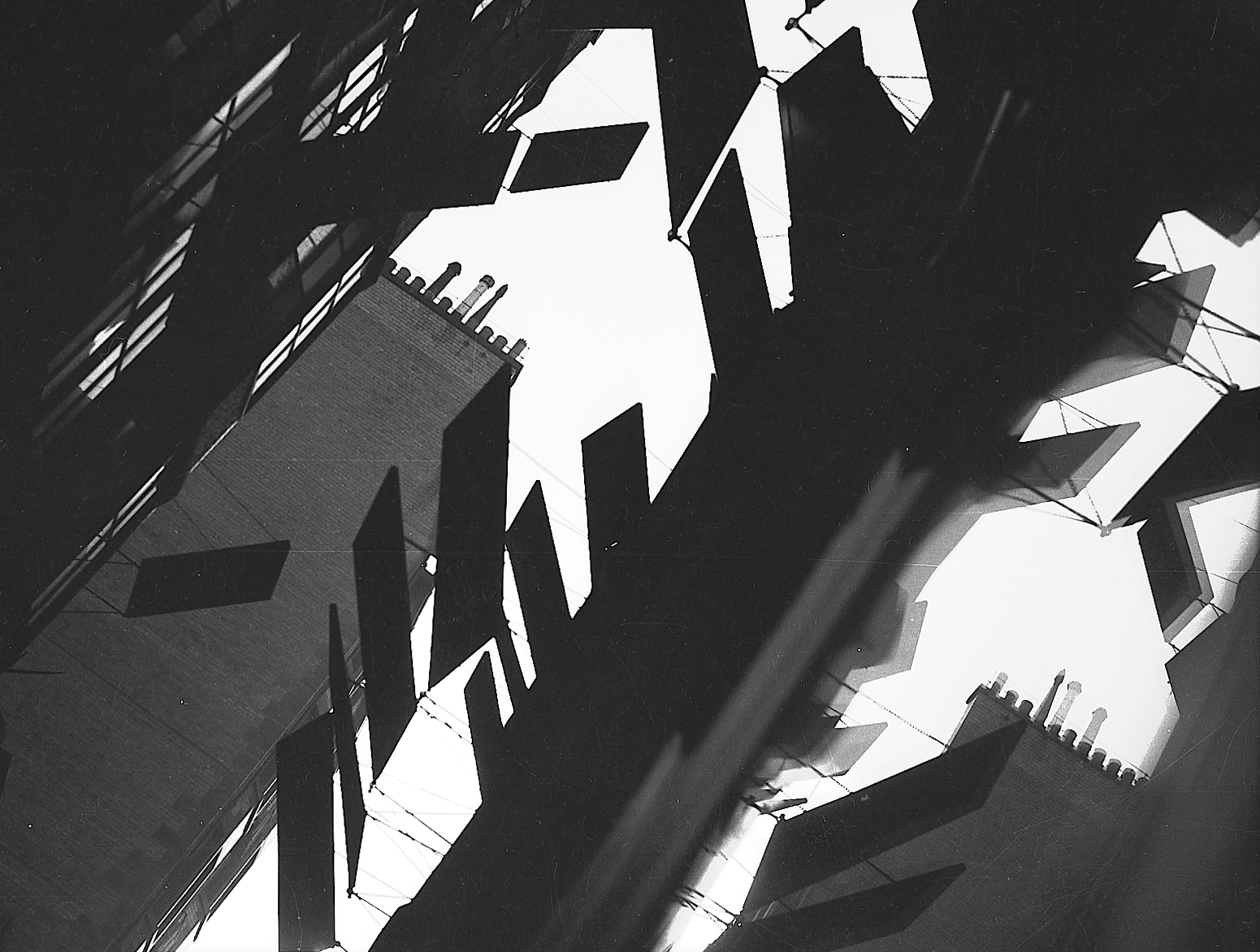

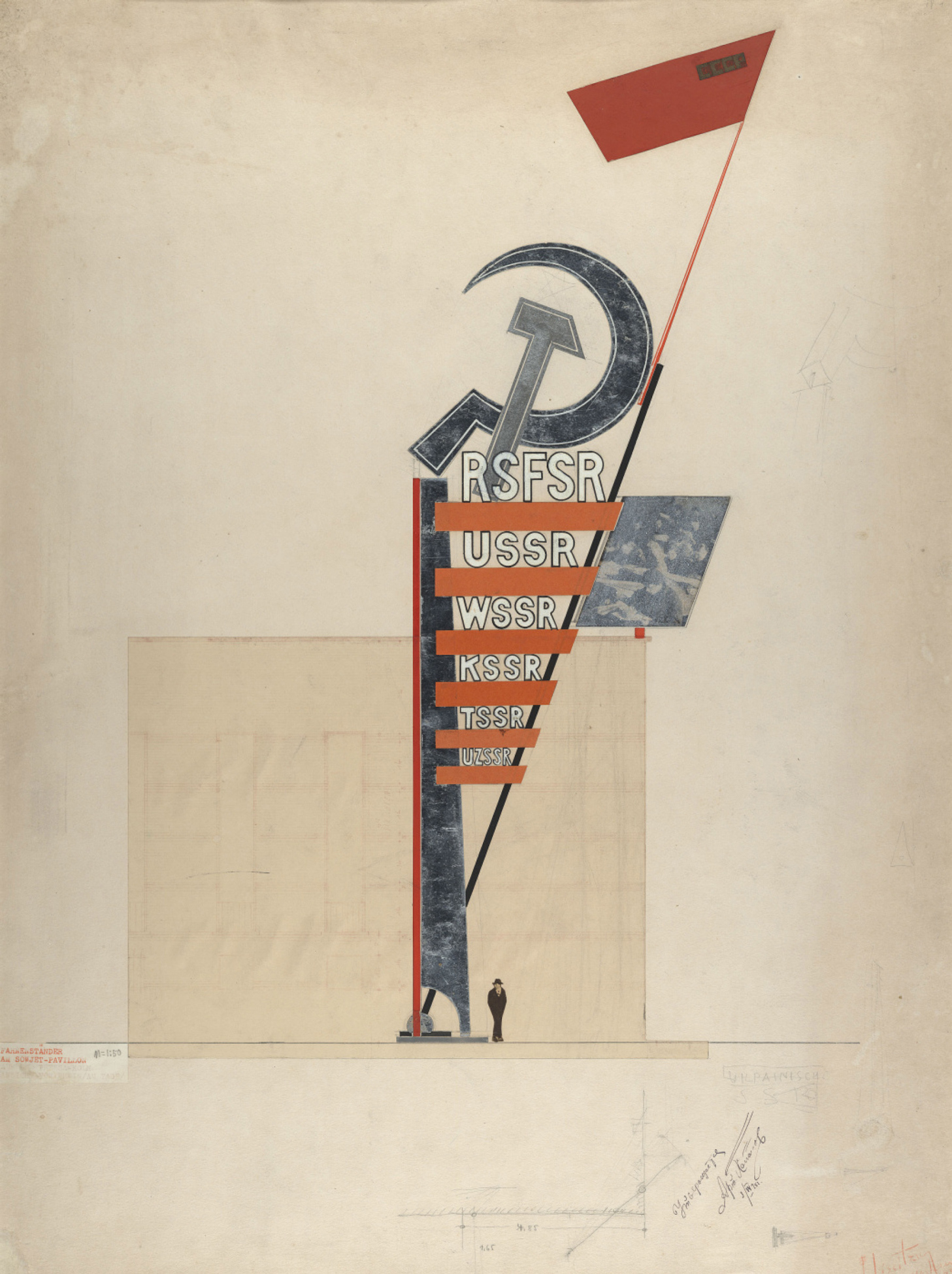

She escaped the aunts three times. In September 1928, she booked a Cook’s tour to Europe along the Rhine, taking in the World Press Exhibition (Pressa) in Cologne, which highlighted the latest in printing, photojournalism, and advertising. This alone was worth the trip, with brilliant displays in the U.S.S.R. pavilion designed by the influential graphic designer El Lissitzky (1890–1941). Watkins loved its “palpitating chaos” and “restless chaotic energy.” Thus began her exposure to the “New Vision” of Europe, where photographers were experimenting with radical perspectives, fragmentation, and other formal methods to find equivalents to the modern machine and the city. She began her own experiments with urban photography. She illegally took photographs inside of Pressa pavilions, and went on to photograph in London for two months.

Despite being tied to the “aunt-hill,” as she called it, Watkins continued to develop her career. In 1928, she exhibited in the London Salon of Photography at the Galleries of the Royal Society of Painters in Water-Colours. In 1929, she pursued her interest in colour photography and enrolled in a course on three-colour printing in Ealing, London. Although she was asked to return, she did not have enough money to do so. Also in 1929, she was elected to the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and became the first woman member of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Photographic Association. She exhibited with this group in 1936 and 1937, winning three prizes—including its highest award, for her work The Princess, 1921.

In Glasgow, Watkins continued to explore the city—its shops, signs, architecture, and workers. Many of her photographs from this time echo the Russian, French, and German photographers of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, which re-embraced realistic representation as a means of social criticism. Her image of two men standing on girders—Untitled [Construction, Glasgow], 1928–38—combines geometric form with the worker in this new industrial world. With the 1932 completion of the Finnieston crane, used for unloading cargo in Glasgow’s Clyde Harbour, Watkins found a sustained subject area: “I almost made a pet of that crane,” she mused in a letter; it looked like “a prehistoric creature.” The giant cantilevered crane haunted Watkins’s Clyde Harbour scenes and also offered her a vantage point—when she dared climb to the top of it—of the city and life below. She did not hesitate to trespass in order to get her shots.

In August 1931, Watkins signed up for the International Congress of Scientific and Applied Photography in Dresden. She had always been interested in how photography could be applied in the commercial world, and not just valued as a pure art form. After the congress, she stayed in Paris for two months photographing street scenes as well as the controversial Colonial Exposition that featured pavilions representing the people, culture, and resources of French colonies around the world.

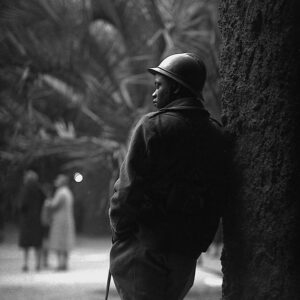

Watkins’s last escape was to the U.S.S.R. in August 1933. Perhaps inspired by the success of her student Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), who photographed the industry of the U.S.S.R., Watkins joined a group organized by filmmaker Peter Le Neve Foster of the Royal Photographic Society and travelled to Moscow and Leningrad. Although not a communist sympathizer, Watkins, along with Bourke-White and others, was curious to see the advances in modernization that the Soviet first Five-Year Plan had made. In New York, Watkins had already developed an interest in Soviet art, and while in Moscow she “assiduously prowled for two half days [and] appreciated to the limit” the Artists of the Russian Federation over Fifteen Years exhibition.

Le Neve Foster gave an account of the trip in the society’s Photographic Journal. The group of five left from London on the Russian ship Cooperatzia. Their schedule was limited by the official travel agency to specific areas—numerable nurseries, maternity hospitals, a workers’ rest home, a communist youth organization (Octobrist) camp, the Park of Culture and Rest, and other parts of Moscow and Leningrad. On one occasion, what Watkins took for workers’ flats turned out to be a barracks and she was escorted off to the police station, where no one spoke English, until the situation was sorted out. They also visited film studios: Soyuzkino, the Soviet Hollywood, and the Red Front, where they met Vsevolod Pudovkin (1893–1953) when Watkins tripped over some bells in the corridor and he came out to see what was happening.

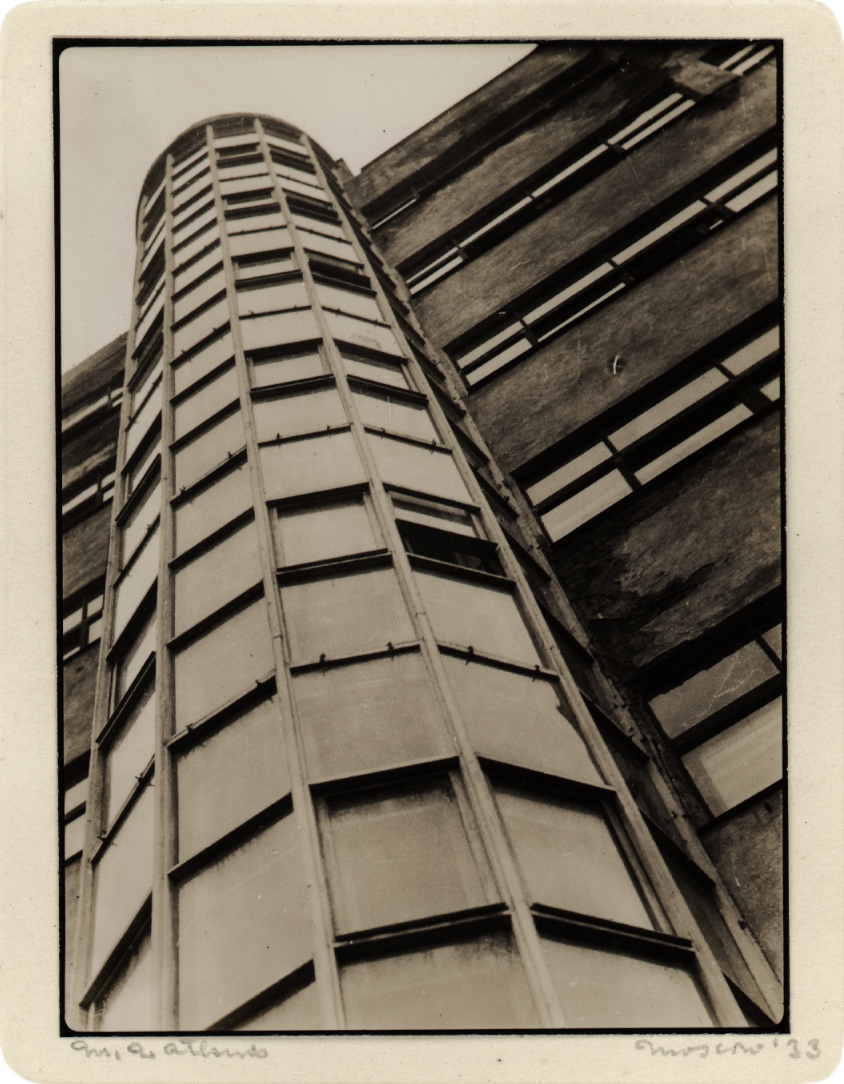

Watkins worked on different photographic series during the trip, one of which she titled Reconstruction, Moscow, 1933, in reference to the Soviet period of establishing new structures (physical, economic, legal, and social) after the revolution and the First World War. She photographed newer buildings, inside and out, but also workers in the act of digging or repairing—often, she noted, with inadequate materials.

She captured the new propaganda as the city was transformed into a talking book. Gigantic posters reoriented their world toward the struggle to create a new utopia. She was torn between the energy these showed and the obvious struggle of those under its weight. Poverty, hunger, and death were visible. Funeral processions passed day in, day out: “It must be bitter aggravation to see foreigners consuming luscious platefuls & know that—unequal relationship between guests and hosts.”

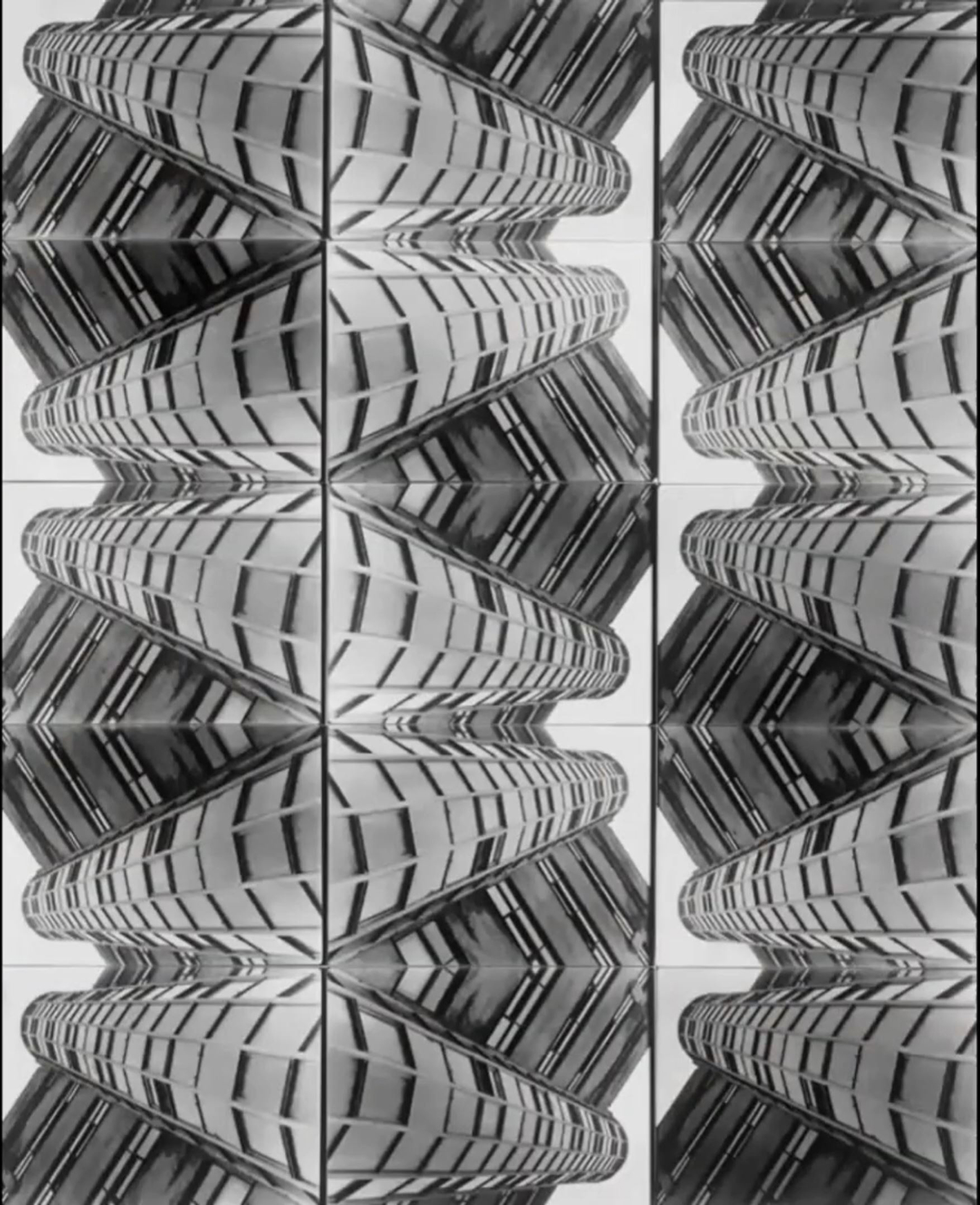

To return to the “aunt-hill” after this trip was especially hard, but Watkins tried for the next four years to keep up her work and hopes. She had an idea of marketing her photographs as designs for textiles, carpets, or tiles. She set to work with kaleidoscopic multiples of her more abstract urban images—of steps in a Glasgow street (Blythswood), the glass and iron roof of London’s Covent Garden Market, the modern façade of the Glasgow Daily Express building, or a detail of a Moscow apartment building. It was like falling into a perfect design, an ordered world of lines and mirroring shapes—pure music in image. Unfortunately, she was not successful in selling them.

From Artist to Archivist, 1939–69

Some artists have short lives and brilliant, but brief, careers. Some have long lives and paint until the end. But the necessary conditions for making art are complex and these two scenarios for creative production are in fact misleading. Watkins did have more than a room of her own, but the house was an albatross. She did not have the 500 pounds a year that Virginia Woolf called for. She was unable to buy photographic supplies and her health declined with recurring pneumonia. Nor did she have the network of like-minded artists and productive institutions as she had had in New York City. She could no longer promote and circulate her work.

Watkins last exhibited her photographs in 1937. The last aunt died in January 1939 and Watkins inherited the Westbourne Gardens home, with its bursting pipes, leaking gas, and a century’s accumulated objects. She had tried an export business sending antiques from the markets in Glasgow to Toronto, where her lifelong friend from Hamilton, Bertha Merriman Henson, would sell them. However, the war intervened and the business failed. By this time her inheritance from Sarah Hutchinson had run out and the house was not sellable. It needed too much work, and nothing could sell during or after the war. She started to take tenants, often people of colour and musicians who would not be accepted elsewhere. One guest was Walter Süsskind, who would later serve as the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s conductor from 1956 to 1965; he left her his baton. Later, a fire in the house made it uninhabitable for tenants.

In the years leading up to her death, Watkins increasingly retreated from society and eventually became a recluse, though her neighbours Joseph and Claire Mulholland who befriended her and welcomed her for Christmas dinner were astounded at her bright mind, her conversation, and her energy. Watkins gave Joe Mulholland a sealed box, asking him not to open it until after her death. When he did, it was filled with her photographs, which had been hidden for thirty years. On November 10, 1969, two days after Watkins’s 85th birthday, she was found dead at home. Reversing the stipulation curtailing her own inheritance from Hutchinson—that the money could be spent on any education except music, a codicil she had obeyed—Watkins left the house to “be put to some musical use, for example, as common rooms, practicing rooms and living accommodation” for musicians. Instead, the old house was sold, and a trust fund was set up to award grants to musicians for continuing studies or specific projects. Even so, it is endearing to picture Watkins herself imagining the future of the space she inhabited for forty years, filled with the music she loved.

In the last phase of her life, Watkins had shifted from being an artist to being an archivist. She continued to read voraciously and listen to classical music, but she also went through all the objects in the house, including her own collection of photographs and documents, ordering and labelling everything. She annotated letters the aunts and her mother had written, correcting information about her life. It is as if she was always waiting for others to find the artist in her once again, to pass on her legacy. And indeed, decades later, Watkins’s work would be rediscovered by a new generation of curators, academics, and photography lovers. Watkins, with her avant-garde way of capturing everyday life, is now recognized as a “revolutionary” modernist photographer and a pioneer in advertising photography. Artists show us new ways of seeing and being in our world. Watkins took her kitchen sink, and later the structures of our cities, and made their mundane everyday-ness, even messiness, come alive with a new sense of balance and harmony.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements