Margaret Watkins is known for her modernist still-life photographs of domestic objects. Her technique was based on a graphic sense of composition, often playing with repeating angles or curves. In the Pictorialist tradition, she preferred low contrast and a long tonal range, especially using platinum or palladium prints. Her modernist, even Cubist, sense of design created a new way of seeing our everyday world as well as a new photographic language for advertising. Under European influence, Watkins later found geometric patterns in industrial subjects and ironic juxtapositions in street scenes.

Pictorialism

Although Margaret Watkins was above all a modernist photographer, the historical context for her earliest work is Pictorialism: the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographic practice that aimed to imitate and emulate fine art using painterly techniques with light rather than oil. Watkins began work as an assistant photographer in Boston in 1913; nevertheless, her introduction to photography as art came in July 1914 as a student at the Clarence H. White Seguinland School of Photography in Maine. Her first commission came the next month, when she photographed an outdoor play at the Arts and Crafts community of the Lanier Camp where she had worked at odd jobs since 1911.

The Lanier Camp promised an antidote to modern industrial and urban life with a simpler, spiritual life, and a return to nature and art. The camp’s series of Bible plays performed in the surrounding pine trees, as depicted in Hannah, 1916, called out for “pictorial” representation. Watkins was already involved as the costume designer for these productions, but once she became camp photographer, her photographs completed for a camp publication became prime examples of Pictorialist techniques—in this case, the Biblical tableau, soft-focus lens, natural setting, and play of light.

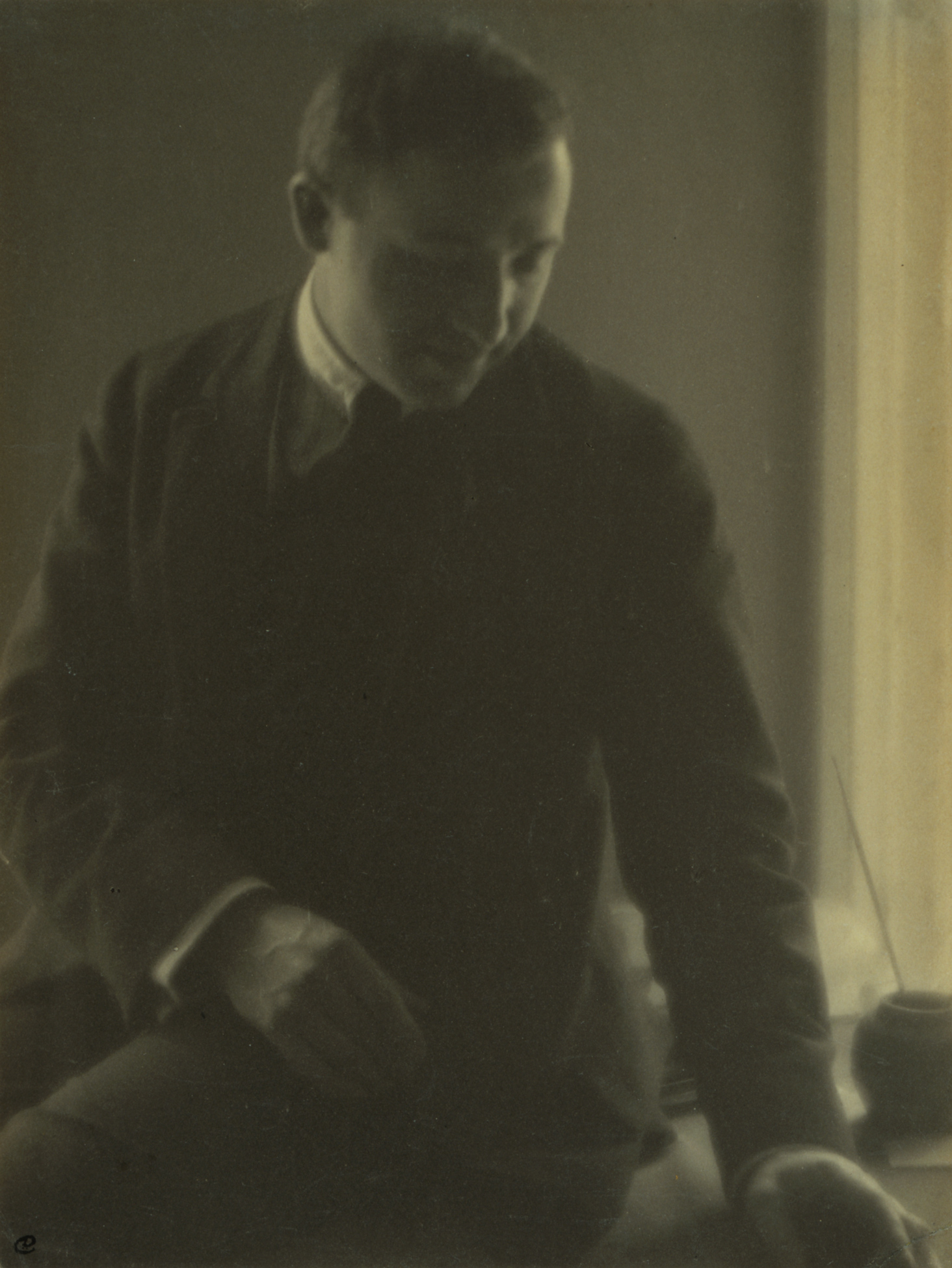

Clarence H. White (1871–1925), with Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), had been a co-founder of the 1902 Photo-Secession, a group turning away from the usual amateur camera clubs, insisting on photography as expressive art rather than a technical way of documenting an object or scene. White was known for his tender, soft-focus depictions of domestic scenes and subjects in nature. And some of Watkins’s early work used a soft-focus lens that captured an ethereal quality in domestic portraits, such as Josephine in Sunlight, c.1916, or in natural scenes, such as her study of poppies in Untitled [Poppies], c.1920.

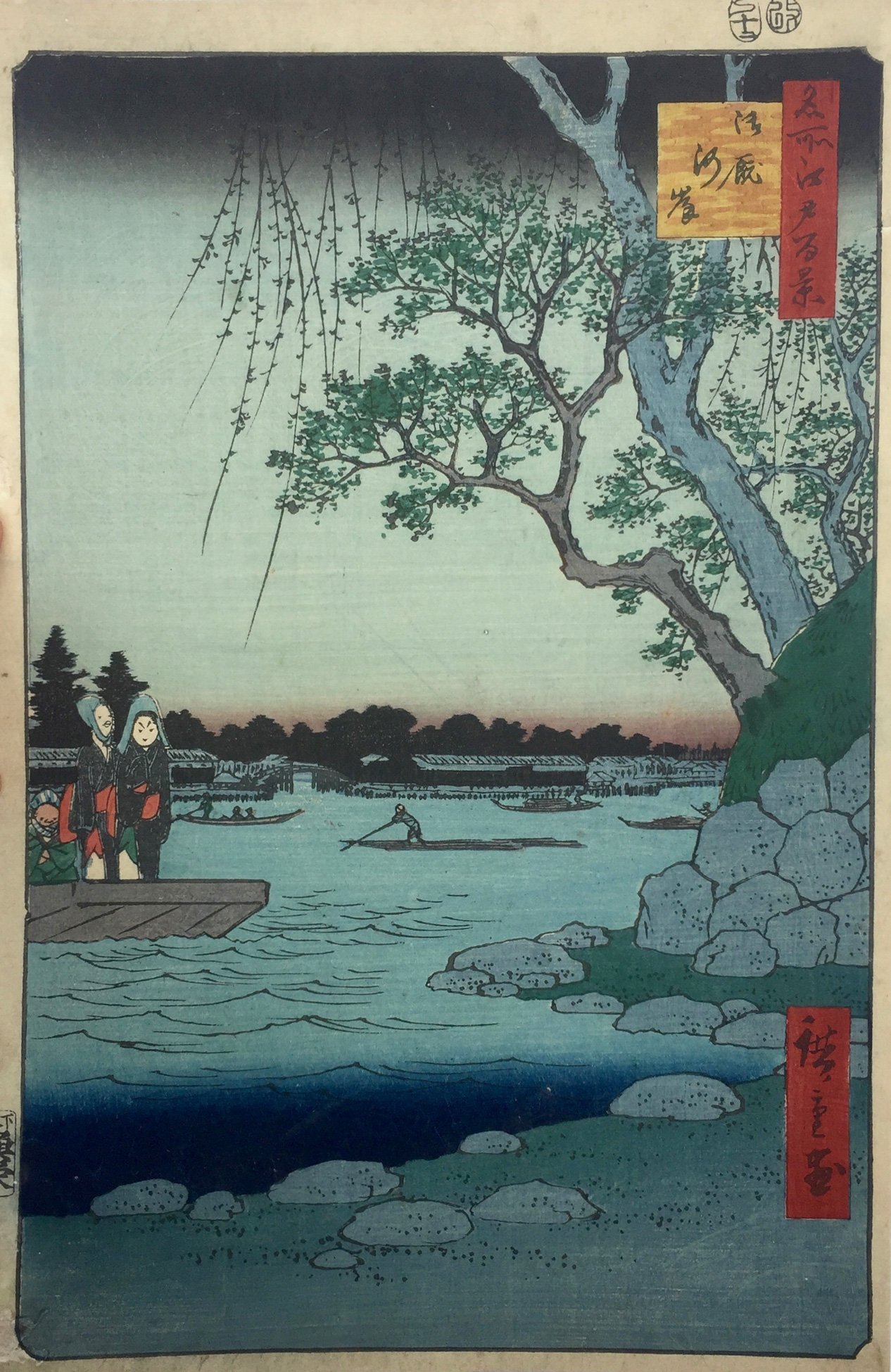

Nevertheless, as art historian Anne McCauley has pointed out, White’s own aesthetic experiments included some modernist techniques, such as the use of empty space, as in his Drops of Rain, 1902. He also passed on to his students the principles of composition developed by Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922), his colleague at Columbia College. Dow’s influential book Composition (1899) was based on his study of Japanese painting and prints. He argued for the quality of notan in a picture, the patterning of light and dark masses and the finding of vertical and horizontal lines in nature. Watkins’s Evening, 1923, has that Japanese quality, with its vertical trees and horizontal bands of variously toned land, water, and sky.

Pictorialists went as far as imitating specific paintings in their composition, representations, and tonality. Both White and Alice Boughton (1866–1943), for whom Watkins worked from 1915 to 1919, used costumes in their genre photographs. Watkins’s photograph Dutch Girl Reading, 1918, imitates seventeenth-century paintings with the girl in her devotions, dressed in period clothes, and chiaroscuro light playing on her face. Watkins’s 1923 portrait of her friend Verna Skelton is comparable to the portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) of modernist author Virginia Woolf’s mother, Julia Stevens, with its isolated face in a dark background.

Cameras and Printing Processes

Kodak’s invention and marketing of the small hand-held camera in the early twentieth century caused the burgeoning of photography as a leisure pastime, particularly for women. However, art photographers preferred larger-view cameras where you could see the image that would be captured. At the beginning of her career, Watkins used a borrowed 4-by-5-inch view camera, but in 1916 she bought herself a 6½-by-8½-inch view camera, comparable to the one her teacher Clarence H. White used.

By the time she moved to Europe in 1928, Watkins had acquired two cameras: her Graflex and “a new little German hand camera.” Expressing some self-deprecation at not keeping up her photography, she wrote to friends that there was “dust on the Voightlander [sic] and rust on the Graflex.” She also notes the serial number of her “Bausch and Lomb ‘Tessar’” lens in her address book. In a 1933 silent film, taken by Peter Le Neve Foster during the Royal Photographic Society trip to Moscow, we see Watkins with a large, top-view, hand-held camera. Although the make of the device is not at all clear, her 1931 Paris photograph of a motorcar’s lamp, Untitled [Self-Portrait], throws back at us a self-portrait reflecting herself with camera.

In 1925, Watkins reminded her fellow Zonta Club members, in a talk entitled “How My Art Enriches Life,” about the labour (and danger) of practising photography: “There is the mean, messy, technical side calling for patience, perseverance, and precision. You roll up your sleeves, play about in poison—keeping the cyanide out of the soup—and work in icy water till the hand hangs dead on the wrist.” Vintage photographs are valued for the quality of their hand-made printing. And there were many chemical processes for developing and printing with light-sensitive precious metals. Through her work as an assistant in portrait studios in Boston and New York, and through her own education at the Clarence H. White school, Watkins mastered, and then taught, most of the processes with which Pictorial photographers were experimenting.

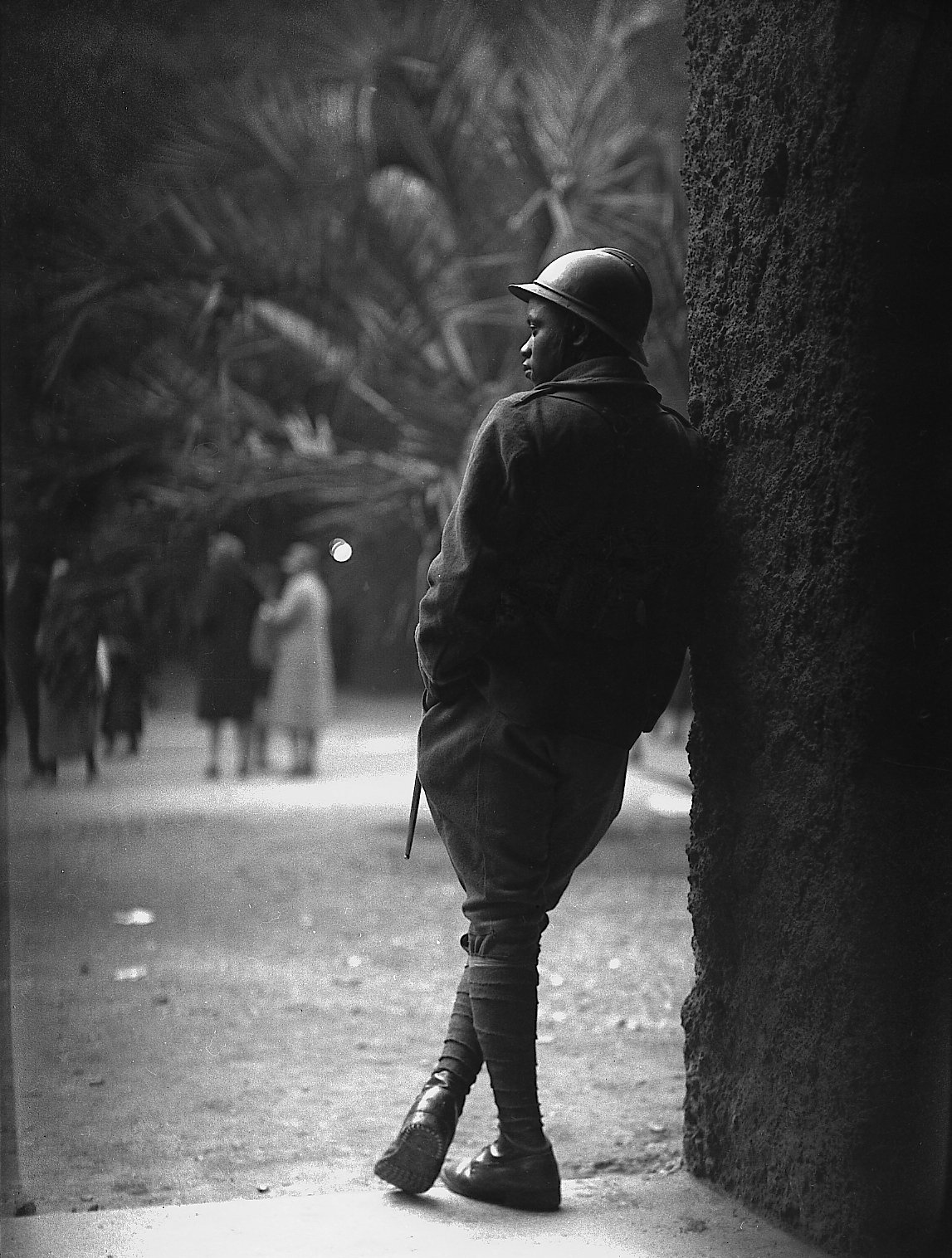

Her extant oeuvre includes prints using various processes such as bromide, chloride, platinum, and gelatin silver. However, like Clarence H. White, she preferred the processes that allowed for a broad scale of greys rather than strong contrasts. Sunset, Canaan, which she exhibited in her solo show at the Art Center in 1923, is a large-scale Kallitype that illustrates how the process’s light-sensitive ferric oxalate provided more definition for shadows. But Watkins is known for the quality of her prints made with the rare precious metals platinum and palladium. In her 1923 exhibition, 38 of the 54 photographs were permanent palladium prints, including The Negative, 1919, and Woolies, c.1920. The vintage process of coating platinum onto the photographic paper was taught at the White school. Needed for industry and armaments, platinum was no longer available for an affordable price by the end of the First World War. There was a shift to palladium, which serendipitously produced a warmer tone. Eventually, even palladium became too expensive. Once Watkins moved to Glasgow in 1928, she developed exclusively in gelatin silver, but still aimed for a range of tones, as in International Colonial Exhibition, Paris, 1931, and Reconstruction, Dining Hall & Workers’ Flats Opposite Kremlin, 1933.

Modernist Composition

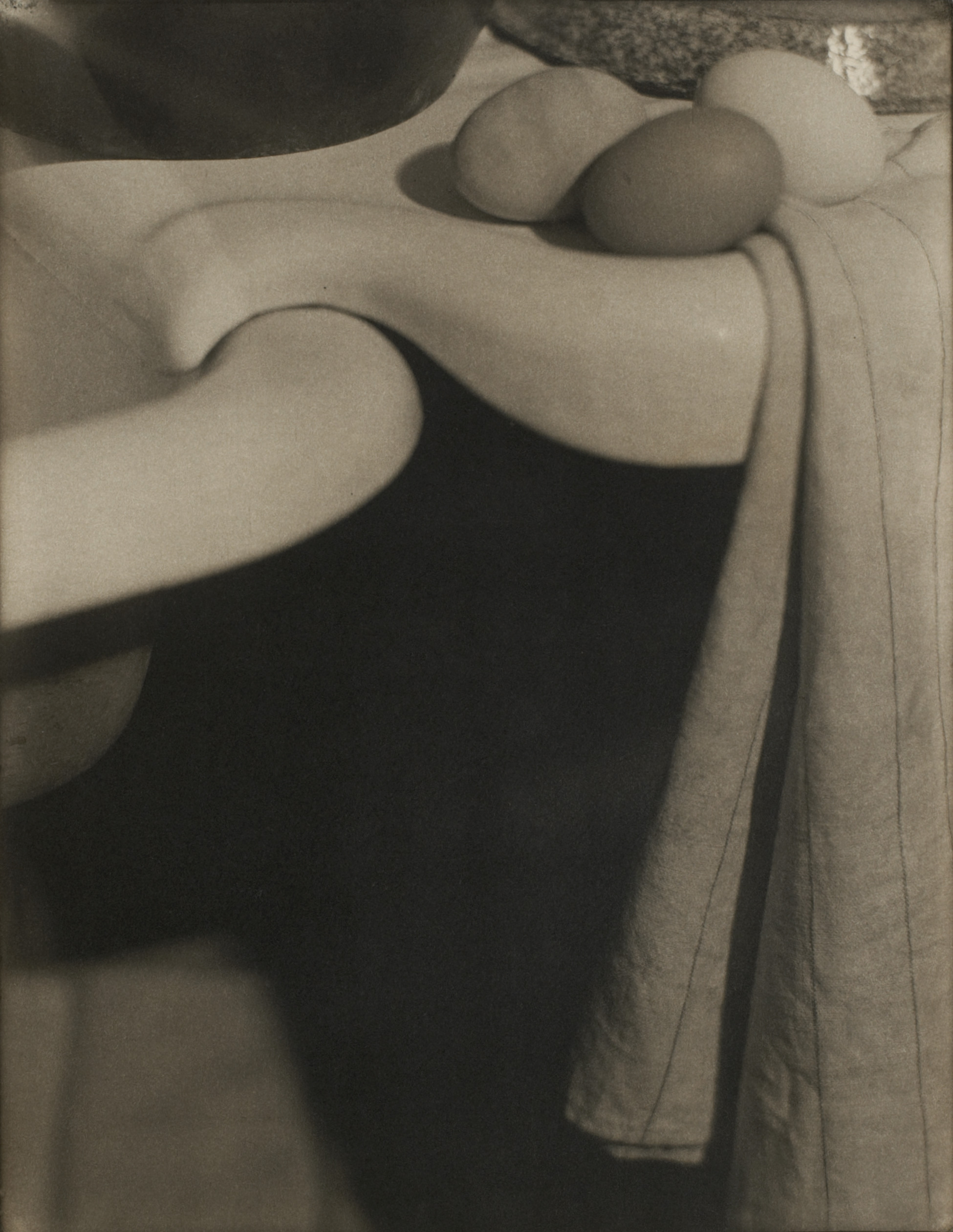

During that first summer at the Clarence H. White school, Watkins also worked with the modernist painter Max Weber (1881–1961), whose teaching of composition and art history was based in Cubist principles. He argued the photograph was a two-dimensional art and must be constructed on the basis of lines, curves, and angles. Weber had lived in France, where he had been influenced by the compositions of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), particularly Cézanne’s understanding that all forms derive from three geometric shapes: the cylinder, sphere, and cone.

The 1914 photograph that Watkins titled Opus 1 is a local harbour scene of fishing boats, but the absence of horizon, the triangular arrangement of the boats and dock, and the empty space at the centre of the photograph turn the scene into a study in design. And this became Watkins’s forte as an artist. By 1921, she was featured in Vanity Fair for “Showing Modernist, or Cubist, Patterns in Composition.” Compared to Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), her photographs were described as “successful attempts to impose a modernist pattern on prints made with the camera.”

Design – Curves, 1919, is exemplary of how Watkins based her aesthetic on formal interests: a photograph of objects reaching toward abstraction. To the formalist, it is an image of shapes and shadows, lines and curves, all asymmetrically balanced. At the centre of the photograph is a dark, curved, triangular shadow, which slides over the rounded porcelain draining board. The curves are repeated in the round board, echoed in its shadow, and the plate’s edge and black border. The diagonal lines of draining rack are echoed in the line of the wallpaper.

Even Watkins’s later portraits are constructed on geometric terms. Her Portrait of Nina B. Price — Abstraction, 1925, shown at the Pictorial Photographers of America International Salon at the Art Center in New York City in May 1925, was described as “a purely geometric design… reminiscent of the idealless prose of Gertrude Stein of ‘Tender Buttons’ fame.” (Such as this: “A feather is trimmed, it is trimmed by the light and the bug and the post, it is trimmed by little leaning and by all sorts of mounted reserves and loud volumes. It is surely cohesive.” ) Watkins’s photograph sets the objects on publicist Nina Price’s desk against the backdrop of Art Deco wallpaper to evoke the characteristic modernity of her sitter. Lampshade and hat, triangles and curves, stand in for face and torso of this avant-garde figure.

Kitchen Still-Life Photography

Taking her Cubist strategies into the home, Watkins is credited with inventing a new genre of photographs: kitchen still-life images. Her experiments were taken to the spaces of her everyday life, placing kettle, pot lids, and milk bottles in her kitchen sink and arranging them into patterns of repeating circles or angles. These were the photographs that would make her name.

Watkins’s compositions are based on Cubist principles, employing disorienting perspectives and fragmented objects. Her 1919 Domestic Symphony offers a glimpse into the dark space underneath a sink, revealing only segments of a white enamel sink and its adjoining draining section and the cropped rounded bases of a kettle and pan on top. The result is a sensation of waving curves. Watkins’s ability to find significant form in repeated patterns of line and tone transformed the domestic world into sensual pleasure.

Still Life – Shower Hose, 1919, again focuses on daily menial tasks of self-care, but this time through the arranging of repeating forms. Light and dark are balanced, moving from the light on the hose and the white towel to the darker wainscoting that recedes to an almost black corner. The positioning of the hose, with its multiple circles balanced against the strong, but not rigid, verticals of pipe, towel, and pendant hose, gives this object a new presence, even as we forget the thing itself. The great achievement of Watkins’s domestic still-life photography is the simultaneity of the mundane object and significant form.

What is extraordinary about The Kitchen Sink, 1919, is this combination of fine form and the messiness of everyday life. The framing triangle created by three dark metal objects is echoed in the bottom edge of the sink photographed from a unique angle. In turn, this off-centred sink with its rounded edge begins a proliferation of seemingly random and incoherent curves of the sink and the cracked, mismatched, and dirty dishes. Watkins’s Design – Curves, 1919, perhaps cleans up the mess into a more abstract image, but she had broken the taboo of photographing in the kitchen, of photographing women’s menial labour, and of making it beautiful. Her play with these objects was varied, startling, new. We talk of innovations in photography as finding a new vantage point—whether it was from the height of skyscrapers, or from an airplane, or underwater. Watkins had found a new perspective—a new space for photography—in her kitchen.

The Advertising Image

Watkins was instrumental in developing a photographic language for advertising. Commercial photographers aimed to make a clear reproduction of the object for sale, what Watkins referred to as a “map.” Instead, Watkins chose modernist techniques of cropping and the formation of abstract design through repeated patterns. The beauty of form would sell the product.

In her 1926 published essay on “Advertising and Photography,” Watkins called attention to developments in art that prepared the way for the new advertising image, stating: “beauty of subject was superseded by beauty of design, and the relation of ideas gave place to the relation of forms. . . . And the purchaser, however indifferent to circular rhythms, unconsciously responds to the clarity of statement achieved by stressing the essential form of the article.”

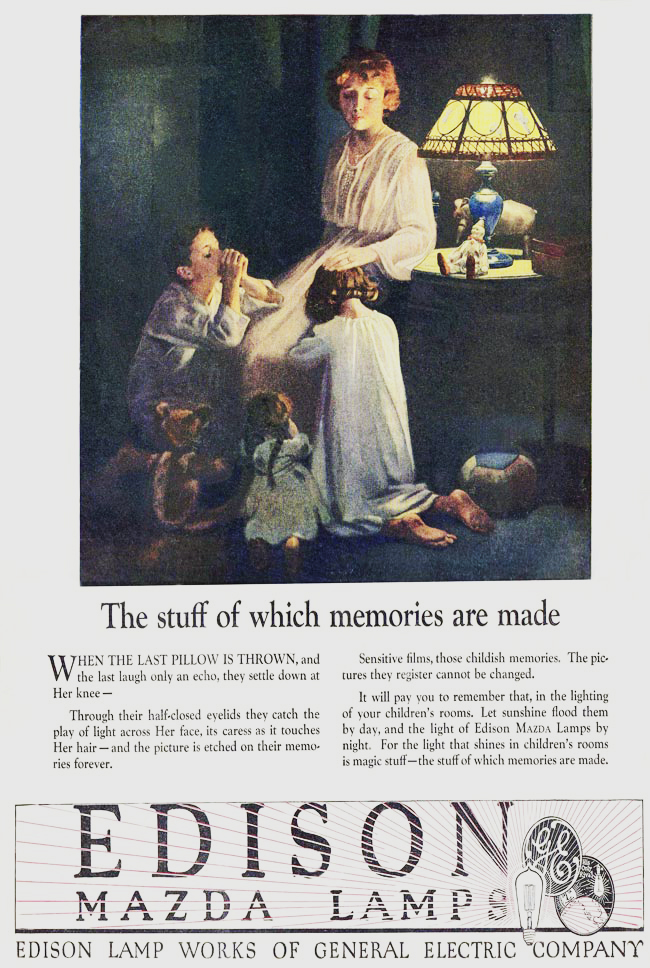

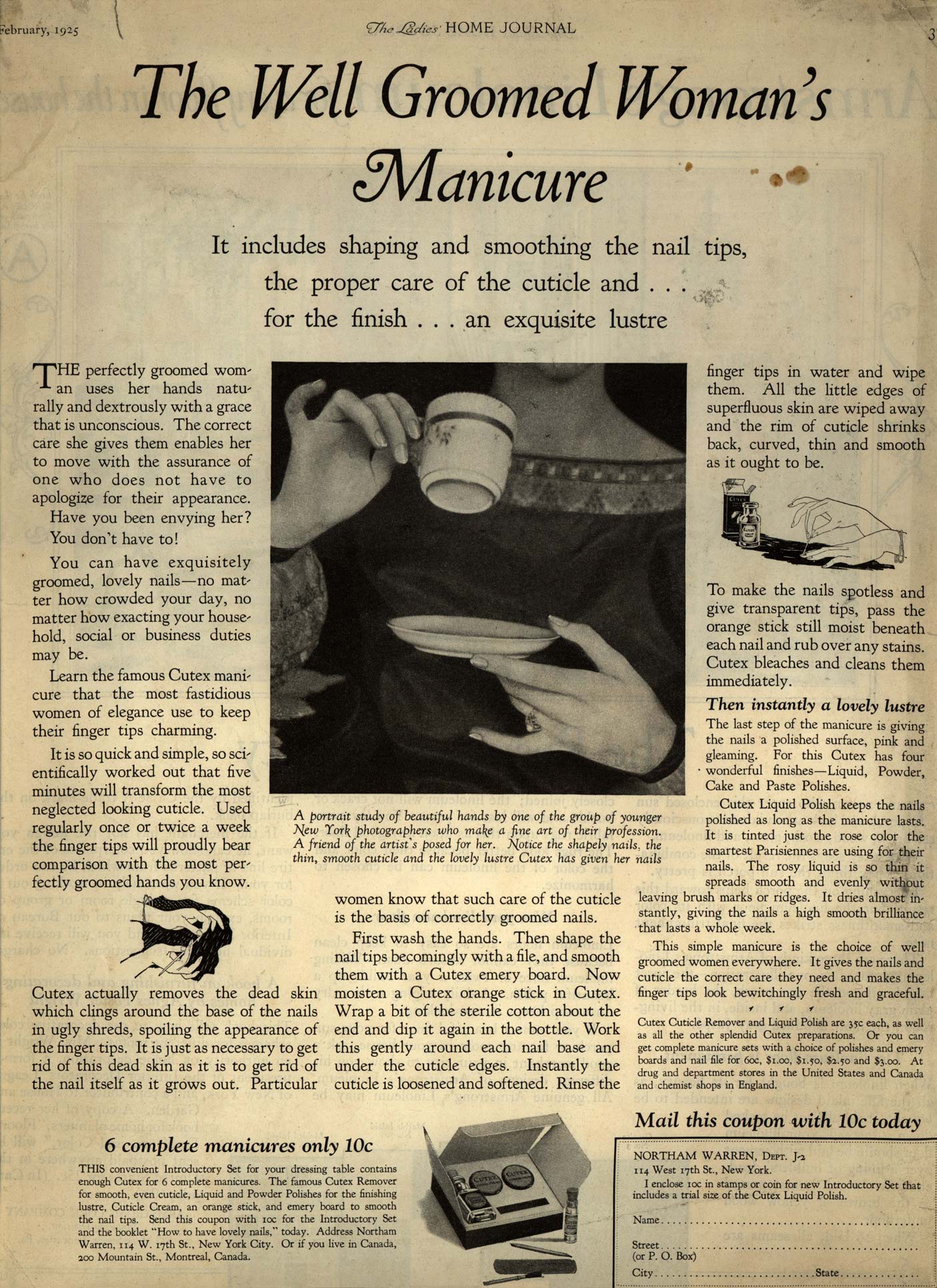

“Beauty of design” and “the relation of forms,” more than the product itself, makes the picture. So, when Watkins prepared her first commission for Cutex nail treatment in February 1924, many of her photographs omitted the bottle of polish. Extending her kitchen still-life techniques of cropping, of building patterns out of repeating circles, curves, or angles, and of blocking gradations of light and dark, she created geometric designs.

In The Tea Cup, 1924, the delicate ringed (and painted) fingers hold cup and saucer, which form the centre vertical axis of the photograph and are balanced by the diagonal of hands emanating from puffed, rounded, lacy sleeves. In fact we again have a design of curves and angles, with the hands and neck forming one triangle, sleeves and dress neckline another (not to mention the edges of the doily or the embroidered designs in the sleeves and neckline).

The truncated body or body part became a standard trope for modernist advertising—the hidden evoked through the detail. The fragment becomes a trace, a hint, a tease. In another Cutex image, Watkins pared her image down to a V-shaped curved line peaking at the centre of her photograph, formed by fingers holding a set of pearls that swing down, presumably from the woman’s neck. The distinct complementary textures of hand, pearls, and furry cuff add to the beauty of the image. Yet beyond pure form, the cuff, pearls, and delicate hand are sensuous. In this case, the trace is not just of a sexual woman’s body but also of money. The ring, the pearls, and the cuff clothe the figure in wealth and worth.

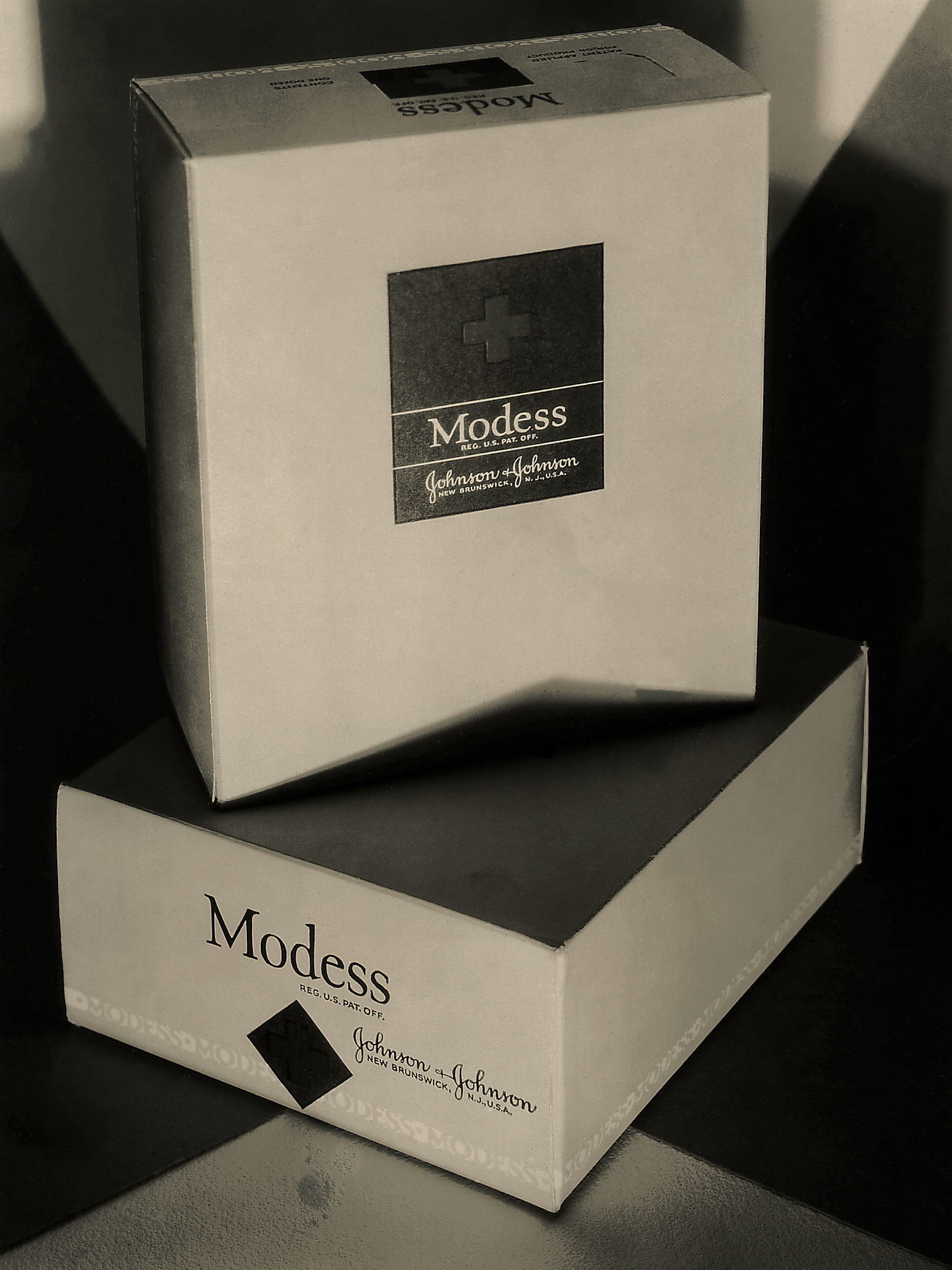

Watkins’s advertising photographs play with femininity as much as formal design. When necessary, they rewrite what is seen as all-too-materially feminine in the new language of stark, abstracted modernity, as, for example, in her brilliant image for Johnson & Johnson’s Modess sanitary pads. By constructing her modernist set with black and white paper backgrounds and judicious lighting to accentuate the geometry, Watkins displayed the rectangular Modess boxes in a contemporary form for the contemporary woman. Modess disposable pads were launched by Johnson & Johnson in 1926, making Watkins’s image one of the first in a long line of advertising campaigns.

Watkins’s marginalia in her copy of the September 1928 issue of Commercial Art are instructive of how she thought of the art of advertising photography. She railed against one image: “The huddle of forms & stupid shadows confuse the eye, can’t find what you are selling and the empty space gapes.” In another comment Watkins noted: “Be sure that the little that is left tells the whole story swiftly & clearly & emphatically…. You must feel the subject photographically and ‘place it’ on the ground glass yourself. Some good technicians merely achieve a perfect map of the object.” In these few notes we have a clear picture of the artist’s eye and her principles: the image should be clear, not with the exact replica of the object, but with its placing in a significant form. The worst fault would be “utter confusion” of shapes, lines, and tones.

Watkins’s photograph for Phenix Cheese illustrates her perfect control of shapes and light. Her by-now recognizable kitchen sink provides the ground for the composition, with its shadow at the two bottom corners offering points of a triangle that lead the eye upwards to connect with the darker background at the top of the image. A silver knife, strategically raised on a round cutting board, leads our eye into the image—a technique borrowed from seventeenth-century still-life paintings. Our eye follows the knife toward a round metal tray of equal value, but filled with a myriad of circular indentations, many collecting crescents of light. (This is the Roycroft copper plate that can also be seen in Watkins’s Still Life – Circles, 1919.) The long block of cheese forms a descending diagonal almost parallel to the knife. And at the centre of the photograph is a balanced pairing of three squares of cheese (two stacked slices and the end of the block) and three rounded shapes of bread (two stacked slices and the front of the loaf). The edge of the block of cheese leads into the line of the edge of the bread. The only break in a perfect balance of circles and squares is the opened jagged foil wrap of the cheese—and the purposeful placement of a few crumbs left on the knife. This photograph is a perfect still life, its busy-ness (and labour) all contained in a seemingly simple, balanced whole.

Late Industrial Photographs

Margaret Watkins’s post-1928 photographs of the city, industry, and workers in Glasgow, Paris, London, Leningrad, and Moscow were influenced by her encounter with the European New Vision. She left her New York studio work of portraits and still-life studies for advertising and took her camera outdoors. In one of the first photographs, on the boat from Dover to Ostend, she looks down into the hold of the ship. The tell-tale signs of Watkins’s work are evident in the multiple rectangles at play, but the defamiliarization and disorientation is even stronger than, for instance, in The Bread Knife (Design – Angles), 1919. Here, one is not sure at all of the subject of the photograph. In this way, her modernist indoor methods of photographing are transferred to an industrial site.

In 1928, she visited Cologne and Pressa, an international exposition of publishing and printing, including reproduction of photography in photojournalism, advertising, or propaganda. There, she encountered the U.S.S.R. pavilion designed by El Lissitzky (1890–1941), full of an extraordinary combination of Constructivist and agitprop (political popular media aimed at conveying communist beliefs) design and photographic montage, all of which she found to be “palpitating chaos” and “restless chaotic energy.” She became familiar with New Vision photographers such as Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), German Aenne Biermann (1898–1933), and Soviets Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) and Boris Ignatovich (1899–1976). Her longstanding interest in graphic design and advertising images would have brought her to Pressa, but her later photography was marked by an increase in its radical perspectives, abandoning an old realism that was no longer valid for the modern, accelerated, and disorienting urban experience. She wrote: “[I’m] only beginning to see fine opportunity for [the] industrial genre.” She went on to create a startling range of urban photographs, from surreal Paris storefronts reminiscent of the urban photographs of Eugène Atget (1857–1927) to the criss-cross of steel girders on a Glasgow construction site.

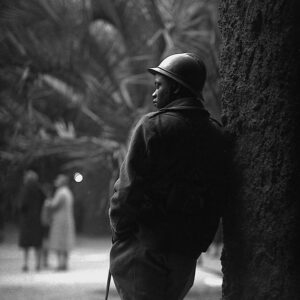

Compare her Untitled [Construction, Glasgow], 1928–38—a single man standing in the midst of a series of diagonal lines formed by the girders of a building site—with Ignatovich’s With a Board, 1929. Or the disorienting perspective of her 1933 detail of a Moscow apartment building with Rodchenko’s Balconies, 1926. And what she did with this image once she got back to Glasgow was indeed original—a new possibility for photomontage, in this case not superimposing one image on top of another, but multiplying and juxtaposing the image to make kaleidoscopic, symmetrical geometric design.

In Paris, London, and Glasgow, her street scenes held the irony and surrealist juxtapositions for which Atget was known. Her Godiva and the Gossips, 1931, picked up the reflections of onlookers in the window display of mannequins and lingerie. In her photo of the So This Is Paris, 1931, advertisement juxtaposed with the man who turns back, Watkins connected the two with rays of light and patterns of light and dark. She had found a language of irony through design, patterning, and juxtaposition.

Watkins’s photographic style thus began with a late nineteenth-century technique of soft-focus Pictorialism, but with hints of the modernist form that would be the strengths of her New York still-life and advertising photographs of the 1920s. In her later photographs of the 1930s, she transferred her Cubist techniques of cropping and surprising perspectives to the cityscapes of Europe.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements