Untitled [Glasgow, Finnieston Crane] 1932–38

![Untitled [Glasgow, Finnieston Crane]](https://www.aci-iac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/margaret-watkins-untitled-finnieston-crane-1920x2568.jpg)

Margaret Watkins, Untitled [Glasgow, Finnieston Crane], 1932–38

Gelatin silver print, 10.3 x 7.8 cm

The Hidden Lane Gallery, Glasgow

Here in a photograph of the midsection of Finnieston Crane in the Clyde Harbour, Watkins works with her industrial surroundings in Glasgow, showing the influence of Europe’s New Vision photography that experimented with innovative angles of vision, radical perspectives, and fragmentation to find equivalents to the modern machine and the city. This photograph offers a skeletal formation of black criss-crossing beams and girders against a curving pattern of white and grey clouds. The crane is cropped, removing any sense of its edges, the ground, or the horizon. Instead, what is left is a 1930s version of Watkins’s design-angles: in this case, not created with a bread knife on her sink, but by the massive crane that she explored from all sides. Comparable to the Eiffel Tower photographed by Germaine Krull (1897–1985), with its interest in geometric form, this midsection photograph of Finnieston Crane is one in a series Watkins took of the cranes by the River Clyde. The series allowed Watkins to explore different viewpoints of the crane in the city—from afar, from its top, and from underneath.

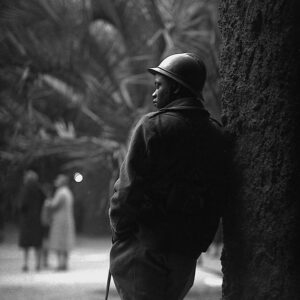

Watkins visited her aging aunts in Glasgow on her way to a European holiday in 1928. Finding they needed care, and being the only unmarried relative, she stayed to help and never returned to North America. She adopted the new industrial landscape of this ship-building city and “almost made a pet” of the Finnieston Crane: “I’ve seen the ship-yard cranes looming in the dusk like a herd of prehistoric monsters—and been shooed away by the watchman—and to see man in his true perspective, as a very small creature creeping and scurrying about the earth.” This is Watkins’s Glasgow: where industry offers her geometric designs, but where she also is captivated by the human in relation to those structures, such as in her image of a man reading by the Clyde, framed beautifully by steel beams and visually in conversation with the haunting crane at the centre of the photograph. Or her view from the top of the crane looking down to trucks and workers below: “There’s a shot from the giant at Finnieston (hanging over the rail in a stiff breeze), looking straight down on the squat dome of the tunnel entrance, with little trucks and figures making a quick beetle pattern of light and dark.”

These photographs of cranes are also comparable to a series of photographs that Watkins did from 1932 to 1938 of workers on a Glasgow construction site. At times she silhouetted one or two men on a criss-cross of girders isolated against the sky. In another, we have a worker amid the confusion of scaffolding beams and shadows. The effect is of a montage highlighting the worker in his environment. These photographs are reminiscent of Russian photographers of the period, such as Boris Ignatovich (1899–1976), Vladimir Gruntal (1898–1963), and Alexandr Rodchenko (1891–1956). Watkins’s own student Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) was also making a name for herself with photographs of monumental industrial sites, for instance in her Otis Steel series and massive dams in the U.S.S.R. If Watkins’s photographs do not always have the monumental thrust of Bourke-White’s images, they have perhaps a more interesting Cubist effect: disorienting but always looking for unexpected symmetries, repetitions, and pregnant unfilled spaces.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements