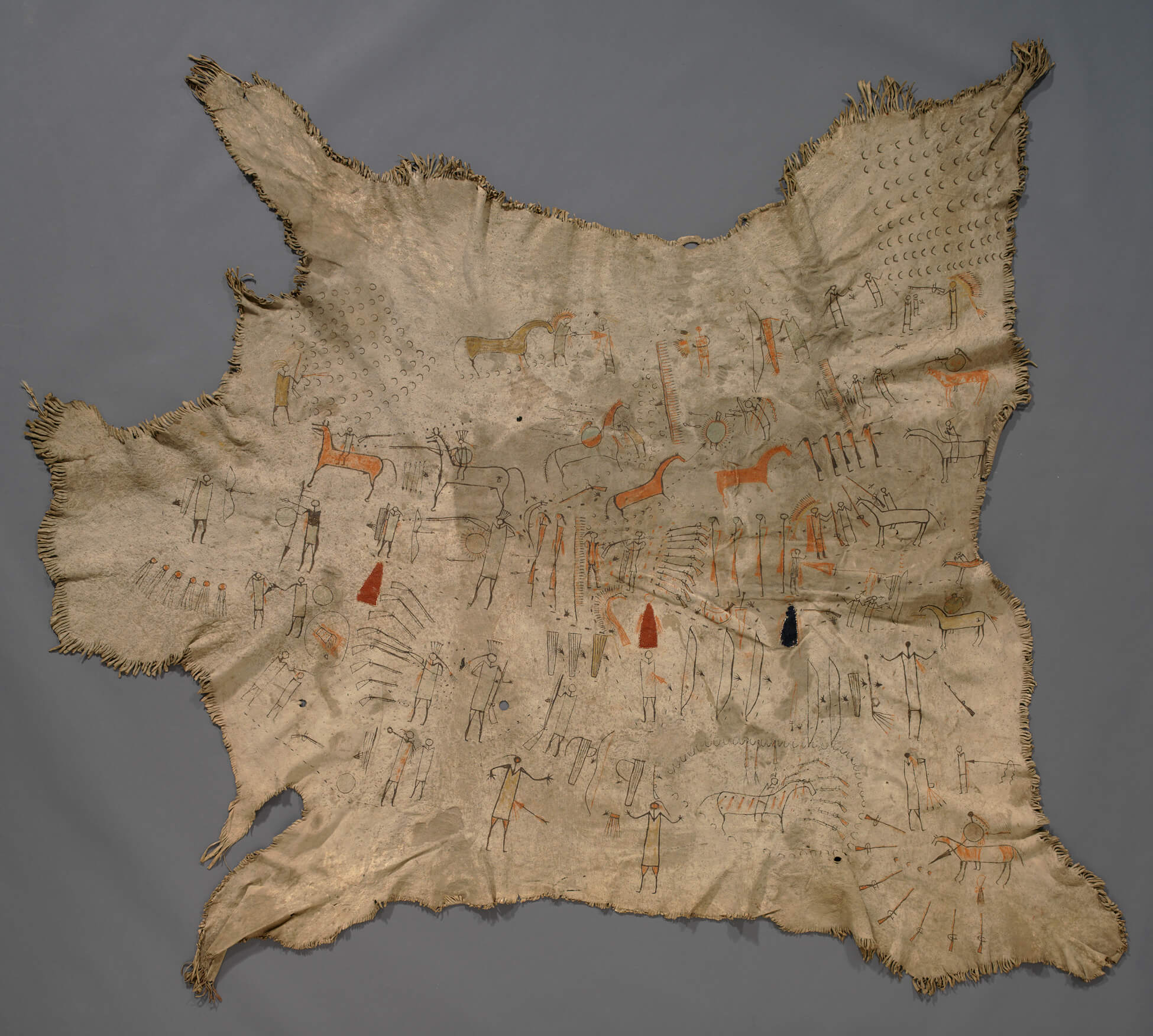

War Exploit Robe c.1830–50

War Exploit Robe, probably Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), c.1830–50

Probably dressed elk skin, painted with hematite, goethite, and green earth pigments, 212.5 x 196 cm

Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

This magnificent war exploit robe is one of few Indigenous war artifacts made of perishable materials that has survived from early contact times. When it is stretched out, it resembles the shape of the animal from which it was made—most likely an elk. It is covered in images of figures with rectangular or X-shaped torsos and V-necked shoulders as well as feather bonnets, horses, arrows, quivers, guns, shields, and bows. Some of the horses are depicted as wounded, but other repetitive markings are less easy to identify, though some depict scalp tallies. Black line drawings make up most of the decorations, and only the centre area of the robe is coloured, with a few images of horses shaded in orange.

In twenty-one separate vignettes, the drawings depict more than eighty war deeds. Some of the scenes focus on a single event while others show a sequence. All of them seem to be performed by one nameless man who is identified only by his straight-up feather bonnet and painted shield. Fifty-two images of hands are found on the hide—each representing the protagonist capturing objects or firing off weapons. In all, this warrior captured thirty-nine objects and wounded or killed thirty enemies. Although the meaning of some of the images decorating this skin is obscure, we know that an accepted pattern of image use akin to heraldry was a feature of warrior exploit robes.

Like many forms of traditional Indigenous art, war robes are closely associated with everyday life and are transportable. The Indigenous peoples of the North American Plains moved about over a large territory as the seasons changed, and their possessions, including their tipi homes—conical tents supported by wooden poles traditionally made of animal skins—were usually carried on horseback. This robe illustrates their system of warrior etiquette and the means they used to document military accomplishments in order to elevate their social positions. The images function as the autobiographical painted record of one accomplished warrior.

This robe was found in Scotland in the mid-twentieth century and its provenance or origin is unknown, which makes it difficult to provide any context about the warrior who wore it or the military encounters it depicts. Before the Europeans came, Indigenous nations had long-standing warrior traditions. The robe may well have been found or purchased by a nineteenth-century trader or soldier, and its recovery underlines the ongoing challenge of visually reconstructing the Indigenous military art from previous centuries in Canada.

The painting Big Snake, Chief of the Blackfoot Indians, Recounting His War Exploits to Five Subordinate Chiefs, c.1851–56, by Irish Canadian Paul Kane (1810–1871), dates from the same period. One figure on the left, whom the artist identified as Little Horn, is wearing a war exploit robe.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements