Art has long been entwined with war. In place of weapons, artists pick up brushes, sculpting tools, and cameras and enter the fray to document, propagandize, critique, or commemorate battles that shape history. In Canada, very little survives of pre-contact Indigenous war art, but inherited skills endure in post-contact Indigenous art and creative traditions produced alongside artworks and objects made by settlers. Official Canadian war art programs launched during the First and Second World Wars, helping to forge a new national identity. Recently, protest art and works responding to contemporary conflicts have come to the front line.

The Age of European Colonization

Little visual evidence of military activity in Canada before 1600 has survived, but ancient weapons from thousands of years ago found in Northwest Coast burial sites provide some clues. They suggest that ceremonies associated with warrior cultures did inspire creativity. In post-contact times, increasing numbers of weapons, armour, and clothing recall the rich traditions of earlier Indigenous visual cultures. However, our best sources for previous military exploits remain the oral histories told by elders and storytellers from Indigenous nations across Canada and the post-contact versions of ancient practices.

Most of the artifacts that recall pre-colonial war art, but were made later, are handcrafted useful items created with a strong sense of design and beauty. In marked contrast to much of the Western, classically imbued, message-laden, but, in practical terms, useless military art, early Indigenous war art is functional as well as ritualistic and beautiful. Ceremonial smoking pipes, specifically calumets or peace pipes, offer one visual record of Indigenous conflict in Canada that goes back far in time. Smoking the calumet cemented military alliances, peace treaties, and other contractual obligations. Their use continues to this day. Traditionally, the stems are long and decorated with paint, fur, quills, and feathers. The bowls are usually carved in stone. It is possible that the Royal Ontario Museum’s early seventeenth-century turtle calumet refers to the common Indigenous name for North America: Turtle Island.

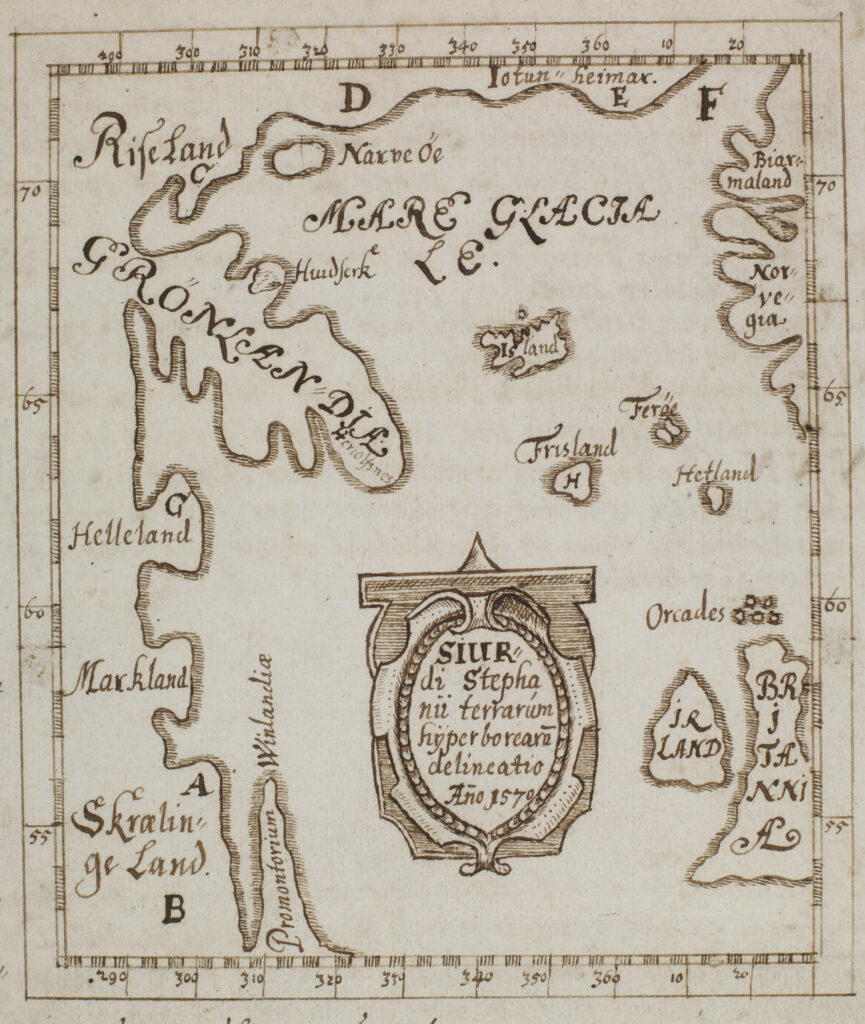

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries—earlier if Viking expeditions are included—explorers and traders from many European countries sought to establish footholds on Turtle Island. From the beginning, Indigenous peoples fought back. The Skálholt Map (1690 copy of 1570 lost original) depicts the occasion when the inhabitants of “Skrælinge Land” (on the bottom left of the map) forced the Vikings back to Greenland (on the upper left of the map) around 1015 CE. But this early success was later rarely replicated. Equipped with guns and other advanced weaponry, Europeans seldom hesitated to use them in their own interests and against Indigenous peoples. Colonization was inherently confrontational for all the parties concerned.

Between 1534 and 1542, French explorer Jacques Cartier made three journeys to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in search of the fabled Northwest Passage to Asia. He claimed this new territory for France, mapped the great river he discovered as far inland as Montreal, and described the Indigenous peoples he found living on its banks. Then he sailed home, without founding any permanent settlement. Illustrated maps and charts became one of the main records of his journeys.

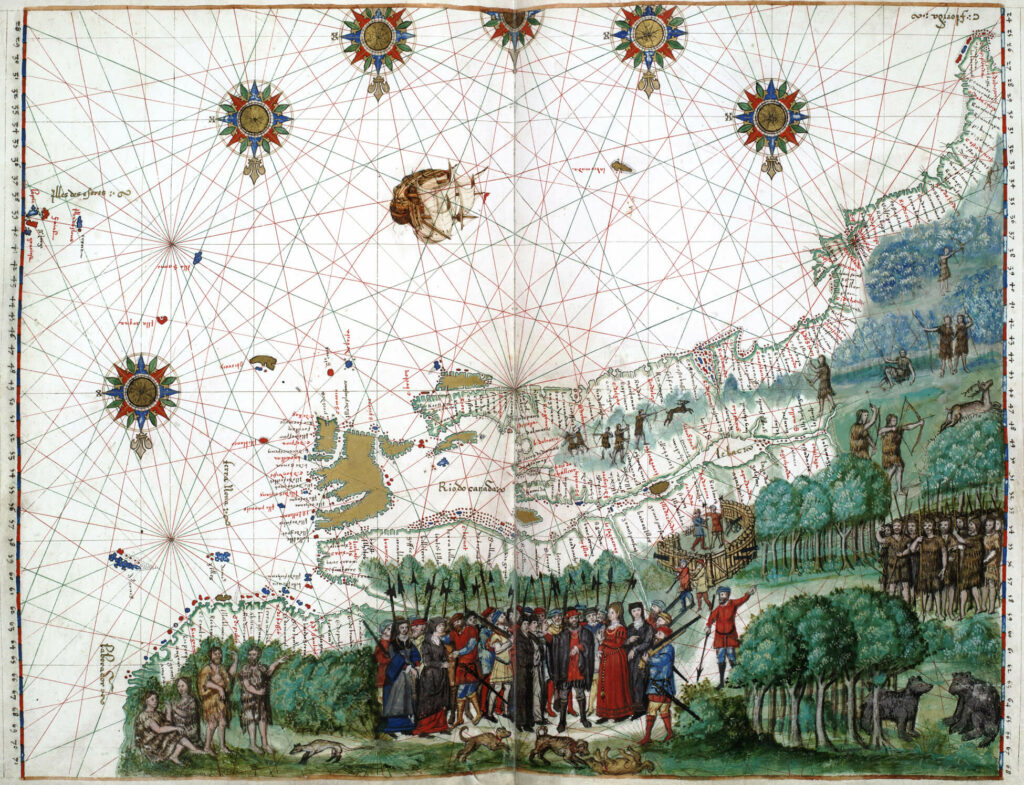

The Vallard Atlas, 1547, is perhaps the most famous collection of early maps to show the east coast of North America. A stunningly beautiful product of the renowned Dieppe cartographic school in France, the atlas visually rationalizes the benefits of conquest in its singular depiction of eastern Canada. The lively weapon-bearing figures that pepper this sheet transform its exquisite imagery into war art. The relative roles of the colonizers and the colonized are made clear: Indigenous peoples are depicted as warring, and the Europeans merely as protectively armed.

Like the French, confident of their own military superiority in the face of local opposition, the British sent gifted seaman and navigator Martin Frobisher, between 1576 and 1578, with ships and men to explore a possible northern passageway to the riches of Asia. On the second voyage, John White (active 1577–93) recorded in watercolour The Skirmish at Bloody Point, Frobisher Bay, 1585–93, an encounter between a group of Inuit hunters and British sailors in which several Inuit were killed but only one Englishman was injured.

In 1608, another Frenchman, Samuel de Champlain, established the first French settlement at Quebec. Anti-confrontational, he dreamed of establishing a new nation in North America based on cooperation and intermarriage between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. His meticulously drawn 1612 map, reproduced for the French print market within a year, includes not only depictions of geographic details such as hills, rivers, and coastlines, but also drawings of the animals, plants, and fruits he encountered as well as full-length portraits of a number of the Indigenous inhabitants.

Yet, while some of his intentions may have been peaceful, to secure French settlement at Quebec, Champlain allied himself with the Wendat (Huron), Anishinaabe (Algonquin), Innu (Montagnais), and Etchemin-speaking peoples living along the banks of the Saint Lawrence River, who were at war with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) further south. As recorded in a drawing published in 1613, Champlain’s party, while exploring the area around present-day Lake Champlain in 1609, encountered a militant group of Haudenosaunee, and a battle ensued. Champlain fired his arquebus, killing two of the group with a single shot, thereby ending the battle but making for the French a permanent enemy.

Increasing conflict led Indigenous residents to form treaties with colonial settlers to bolster their own positions. Along with calumet ceremonies, Indigenous peoples from the Great Lakes to Prince Edward Island used beautifully woven purple-and-white shell sashes known as wampum belts for ornamental, ceremonial, diplomatic, and commercial purposes and to record peace treaties and other alliances. The Teioháte Kaswenta (Two Row Wampum Belt), 1613, recorded the first peace treaty made in upstate New York between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch government. Although the original no longer exists, oral tradition and later written records still seek to enforce some of the regulatory intentions visualized in the lines of purple-and-white shells that are equal and do not interfere with each other.

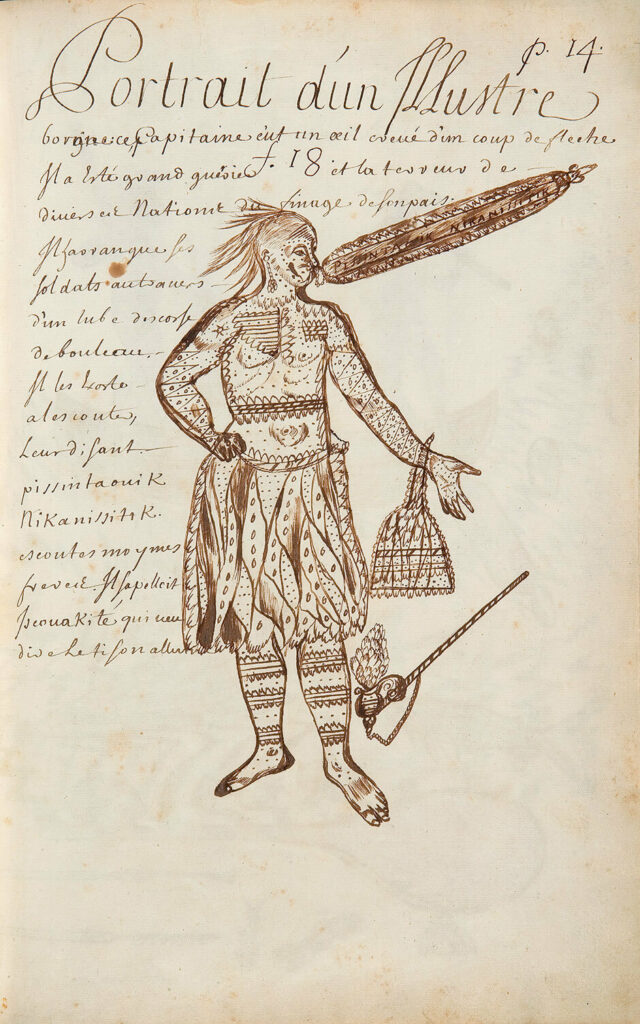

Subsequent history, however, shows that colonial powers did not generally respect these sacred covenants. Most of the newcomers who followed Champlain to New France came for reasons of conquest and economic and social advancement, and to convert the country’s inhabitants to Christianity. Conflict became a way of life in Canada for the original inhabitants and the new settlers as both strove to keep control of land and resources. Indeed, the Haudenosaunee remained formidable opponents, as depicted in Portrait of a Famous One-eyed Man (Portrait d’un Illustre borgne), n.d., a small, elegant rendering of an identified, heavily decorated warrior by French Jesuit missionary Louis Nicolas (1634–post-1700).

One unique artifact tells us about a violent Indigenous encounter of the time. In 1904, Mesaquab (Jonathan Yorke), an Ojibway from Lake Simcoe, Ontario, used porcupine quills and sweetgrass to reproduce from memory, on the lid of a birchbark box, a battle scene originally painted on a rock at Quarry Point, Lake Couchiching, Ontario, some two hundred years earlier. The fact that the rock had fallen into the water was likely the impetus for his work. Framed by two trees, the relatively simple linear design features two armed Ojibway warriors, both holding clubs. On the ground, a small bow and arrow–wielding Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) man either awaits death or surrenders.

French and British Struggle for Control

By the mid-1700s, France and Britain, along with their Indigenous allies, were locked in battle for control of North America. France regarded its colony of New France not only as a source of natural resources, especially furs, and as a market for products made in France, but also as the permanent location of a well-governed Christian society in North America. To this end, paintings and small sculptures imported from France were used in churches and in civic and religious institutions. Some itinerant artists came too, and portraiture reached a high level of sophistication. The anonymous portrait of the Marquis de Boishébert, c.1753, for example, depicts the Quebec-born leader of the resistance to the British expulsion of the French Acadians from New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island in 1755.

In contrast to the relative scarcity of war art in New France, British military art proliferated. Once Britain opened the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, England, in 1741, the graduating student officers were well trained in drawing and watercolour techniques to record the armed infrastructure and skirmishes in the British North American colonies. To be useful to the military authorities, their work had to be correct and accurate, but it could also be marketed to a public anxious for British success. Drawings and watercolours by Hervey Smythe (1734–1811) and Richard Short (active c.1754–66), for example, were converted into prints to spread knowledge of British expansion. In 1761, Short’s sketches became the basis for a set of prints depicting the British conquest of Quebec City two years earlier, showing the devastation in vivid detail as soldiers and citizens viewed the aftermath of the battle. Charles Ince (active 1750s) witnessed Louisbourg’s total destruction in 1758 and drew it as the siege began. His drawing was later a widely circulated print. Thomas Davies (1737–1812), a Royal Artillery officer, painted A View of Fort La Galette, Indian Castle, and Taking a French Ship of War on the River St. Lawrence, by Four Boats of One Gun Each of the Royal Artillery Commanded by Captain Streachy, 1760, which, as the title suggests, contains a large amount of documentary information—not only about the fort, but also the river battle and clothing worn by two Indigenous observers.

Celebrated artists in Britain also represented events in Canada. They created paintings for British audiences which, when publicly displayed, reproduced, and circulated as prints, informed people of their country’s military successes and fostered a sense of national identity. One of the best-known artworks in the National Gallery of Canada is The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West (1738–1820), a romantic and largely imagined rendition of the British commander’s last moments. Wolfe had defeated the French general, the Marquis de Montcalm, at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec in 1759, turning the conflict between their two countries in Britain’s favour. After two centuries of rivalry for control of North America, Britain finally defeated France in 1763 at the end of the Seven Years’ War. France gave up its “Canadian” colonies to Britain, marking the end of New France and the beginning of a new regime, British North America.

A Garrison State

Following the 1775–83 American War of Independence (and Britain’s loss of what is now the United States), Canada became a garrison state, with the British Army much in evidence. Military leaders, including Indigenous leaders, were represented in paintings to support, as always, the sensibility of mutual cooperation rather than conflict. A celebrated but likely posthumous portrait, Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant), c.1807, by German Canadian William Berczy (1744–1813) depicts the Kanien’kehá:ka leader in a classical pose and clothing that incorporates Indigenous accoutrements. Originally from lands in what is now New York State, Thayendanegea and his followers relocated to Canada after the American War of Independence as they had fought for the British.

Similarly, Irish artist Solomon Williams (1757–1824) painted a portrait, Major John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen), c.1804, of the Kanien’kehá:ka war chief (and Thayendanegea’s adopted nephew) who, alongside the British, led the Indigenous forces against the Americans at the Battle of Queenston Heights during the War of 1812, 1812–15. Teyoninhokarawen’s combination of Haudenosaunee and British clothing reflects his own dual heritage and the ongoing cultural exchange between Indigenous peoples and Europeans.

Artworks created by British military artists in Canada in the early nineteenth century support the view that the period was one of non-confrontational harmony. One important monument in Quebec City by John Crawford Young (1788–c.1859), the classically conceived Monument to Wolfe and Montcalm, 1827, combines the enemies in a single memorial that actively promotes unity in a colony that was far from unified. Similarly, the relaxed appearance of the man, boy, and dog strolling leisurely along a forested path in Road Between Kingston and York, Upper Canada, c.1830, by James Pattison Cockburn (1778–1847) belies the road’s important role as a military transportation route, one that has been cut and levelled by backbreaking soldier labour. The British Army played a critical role in suppressing the rebellions of 1837, when colonists in Lower and Upper Canada led armed uprisings in the hopes of achieving greater control in government. These events rarely appeared in artworks, though the Battle of Saint-Eustache, a conflict in the Lower Canada Rebellion, was recorded in a print published in 1840.

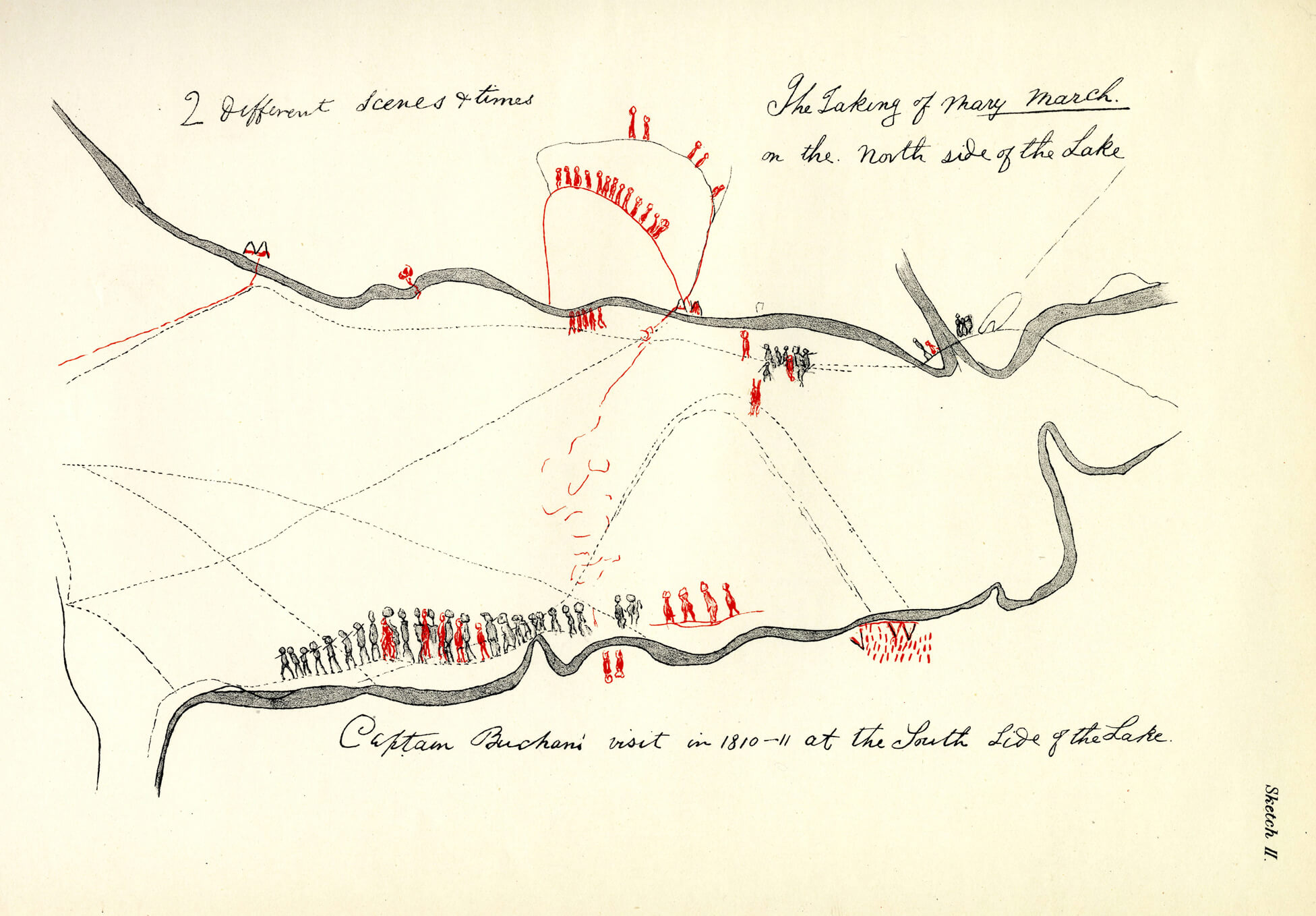

Shanawdithit’s 1829 drawings of her aunt Demasduit’s tragic story represent powerful alternative images of the consequences of colonization at this time. Demasduit was a Beothuk woman, one of the last of the Indigenous peoples who traditionally occupied Newfoundland. In pictograph form, Shanawdithit narrated the consequences of what in Western eyes was an illegal act. In 1818, a group of Beothuk had stolen a boat and some fishing equipment. Eight armed male colonists were sent to recover it. Demasduit was captured in the ensuing skirmish, and her husband, a chief, was killed as he attempted to prevent her capture. Her infant son died a few days later. Demasduit herself died in 1820, only a year after her capture. In 1823 some European furriers found Shanawdithit, her mother, and her sister all starving and brought them to St. John’s. Her relatives soon died of tuberculosis, and Shanawdithit went into service. In 1829, she herself died. She was the last known Beothuk.

A growing overseas interest in Indigenous conflict encouraged Western artists to depict such scenes for colonial audiences, thereby strengthening misleading and violent stereotypes of Prairie warriors. Between 1849 and 1856, for example, in The Death of Omoxesisixany (Big Snake), Irish-born Canadian artist Paul Kane (1810–1871) painted the dramatic death on horseback of a Piikani chief at the hands of a Cree warrior. Kane, who had travelled across Canada, heard about the event and reconstructed it in his imagination, inspired by paintings of European equestrian duels that he knew through reproduction. Kane was also a collector, and he incorporated into his scene the image of a Cree warrior’s shoulder bag he possessed. Dramatic, intense, and visually compelling, The Death of Omoxesisixany (Big Snake) was the only Kane painting to be mass-produced and marketed in its own time. The public was hungry for a taste of the “wild west,” and this image met expectation more than it reflected reality.

On the Northwest Coast, Indigenous peoples in Canada had millennia-long traditions of warrior art. Haida warriors wore armour including helmets, visors, and breastplates. Some of this protective covering was beautifully decorated, as can be seen in the wooden seal’s head–shaped war helmet with copper teeth and eyes, in the Canadian Museum of History. Until contact with colonists introduced the Haida to guns, clubs were among their favoured weapons. One pre-1778 example from Nootka Sound—likely ceremonial—features a fearsome carved wooden salmon head with glaring eyes, a stone club forming its large, protruding tongue. It is further dramatically embellished with human hair and sea otter teeth. It may have belonged to a hereditary chief and symbolized, through his identification with the salmon, his power in and over the present and future living world.

As Canada expanded from its coasts into its geographic centre, colonizers collected information about Plains warriors and their battles via their art. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, nomadic Prairie warriors inscribed stories of their victories onto buffalo and deer hides. These warriors wore the robes to prove their status within the community and to narrate their brave deeds, as illustrated in the expressive pictographs drawn in earth-toned stylized form on animal skin. In compelling detail, one splendid robe (probably Niitsitapi [Blackfoot]) in the Royal Ontario Museum depicts twenty-one separate martial stories that include the capture of weapons and the injury or death of many enemies. Clothing was decorated with slashes and cuts representing arrow and lance injuries, particularly on men’s shirts. Rock faces also attracted images of battles won, as in the 250-character petroglyph battle scene at Áísínai’pi (Writing-on-Stone Park) in Alberta from the late 1800s.

The Confederation Era

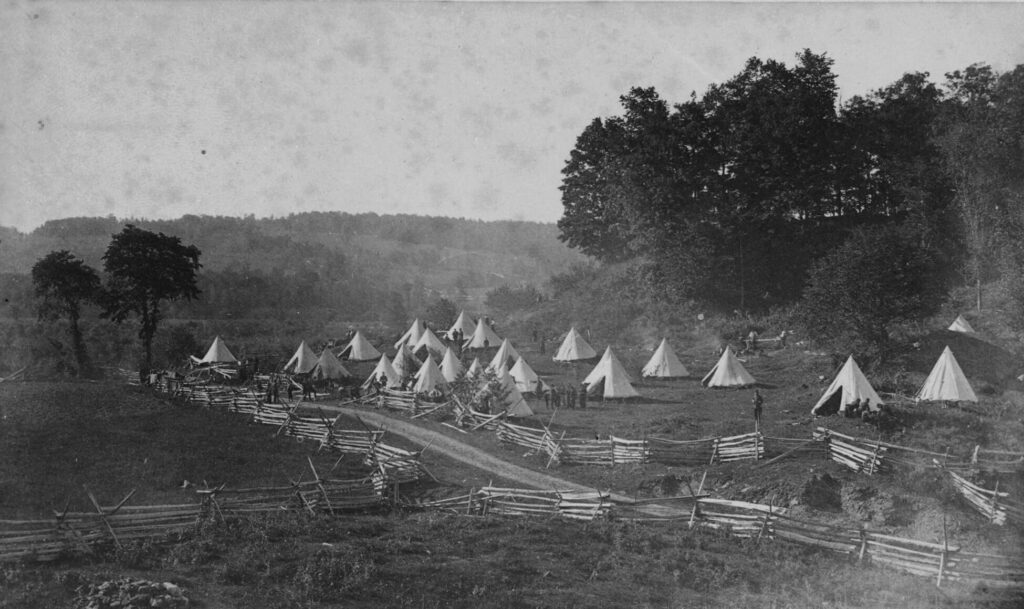

In the immediate aftermath of Confederation in 1867, an event that had united Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick in a new dominion within the British Empire, violence once more appeared, now to be recorded in photography, a new technology that had been invented in France in 1839. The Fenian Raids, 1866–71, were the first skirmishes to be photographed in the new Canadian nation. The Fenians, Irish immigrants from the United States, believed that their capture of Canada, if successful, could persuade the British government to exchange the dominion for Irish independence. The professional appearance of the government’s tents and military paraphernalia in The Pigeon Hill (Eccles Hill) Camp of the 60th Battalion, 1870, by Canadian painter and photographer William Sawyer (1820–1889) shows how seriously Canada took the Fenian threat.

The Northwest Resistance of 1885, in what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta, resulted in the death of hundreds of government troops, Métis militants, and First Nations warriors. Incoming Western settlers feared the First Nations and Métis populations already established in the area, while the Indigenous groups wanted to prevent increased British subjugation and the loss of their lands. Inspired by Métis leader Louis Riel, the Indigenous people set up a provisional government, which Canadian military action rapidly rendered powerless. Later, Riel was hanged, but he remains an enduring symbol of linguistic, racial, and religious discord in Canada.

The conflict is remembered in many monuments, some honouring the colonial militia, and others their Métis and Indigenous opponents. “Sewing Up the Dead”: Preparation of North-West Field Force Casualties for Burial, 1885, a photograph by Canadian soldier and photographer James Peters (1853–1927), reveals the brutal consequences for both sides. Photography also captured Riel’s trial—as in Louis Riel Addressing the Jury during His Trial for Treason, 1885, by American photographer Oliver Buell (1844–1910).

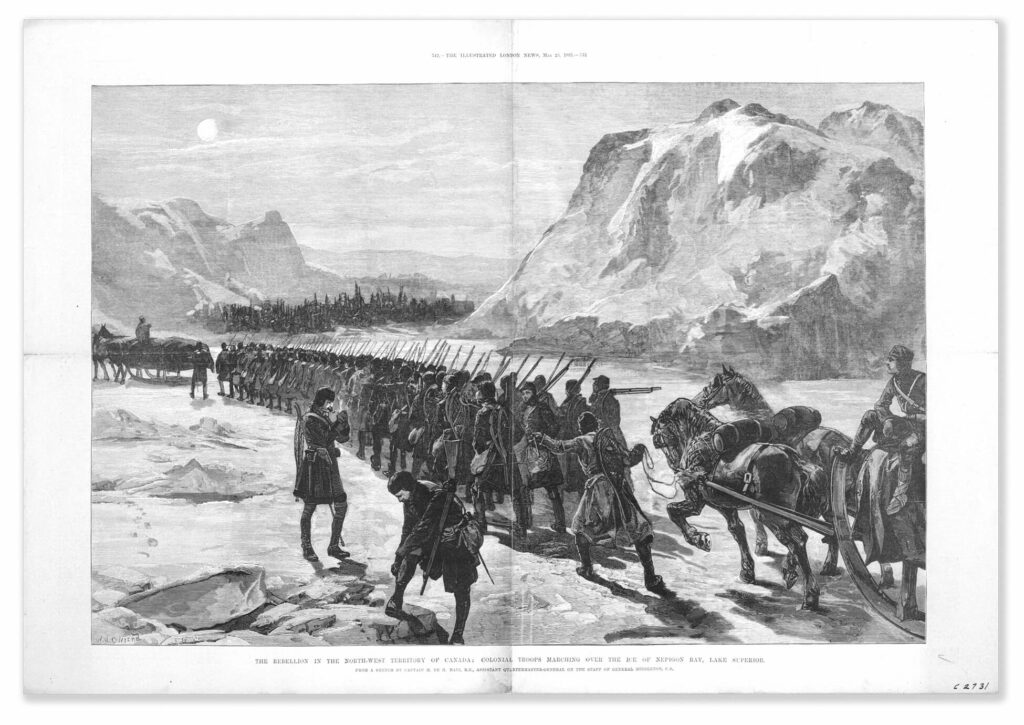

The work of graphic artists employed by British weeklies also records the military aspects of the Resistance in fine reproductive technology—for example, in the illustration of chilly colonial troops on the march, The Rebellion in the North-West Territory of Canada: Colonial Troops Marching over the Ice of Nepigon Bay, Lake Superior, 1885, by British soldier-artist Herbert de Haga Haig (1855–1945). The Graphic and the Illustrated London News often touched up original drawings for greater visual impact, while The Sphere published unaltered sketches. Sadly, the few Canadian magazines that existed at this time were at most regional and short-lived.

In the years after the 1885 Resistance, Canada seized increasing power over Indigenous peoples on the Plains, forcing them onto reserves, establishing the residential school system—and collecting more and more Indigenous art. Early photographs provide revealing visual records of Plains warriors and their associated regalia, such as coup sticks. These objects—notched poles adorned variously with feathers, fur, leather, paint, beads, and other ornamental elements—are associated with “counting coup,” a scoring system adopted post-contact by many of the Plains tribes to document battle deeds. For a coup to count, it had to be witnessed by other warriors and be officially recognized by a tribal council. Canadian photographer, artist, and ethnologist Edmund Morris (1871–1913) recorded the documentary and ceremonial dimensions of historic warrior culture and the great beauty and craft of the artifacts associated with it—as in his 1907 image of Piikani chief Stamiik’siisapop (Bull Plume) carrying his notched and feathered coup stick alongside Minnikonotsi (Man Angry with Hunger).

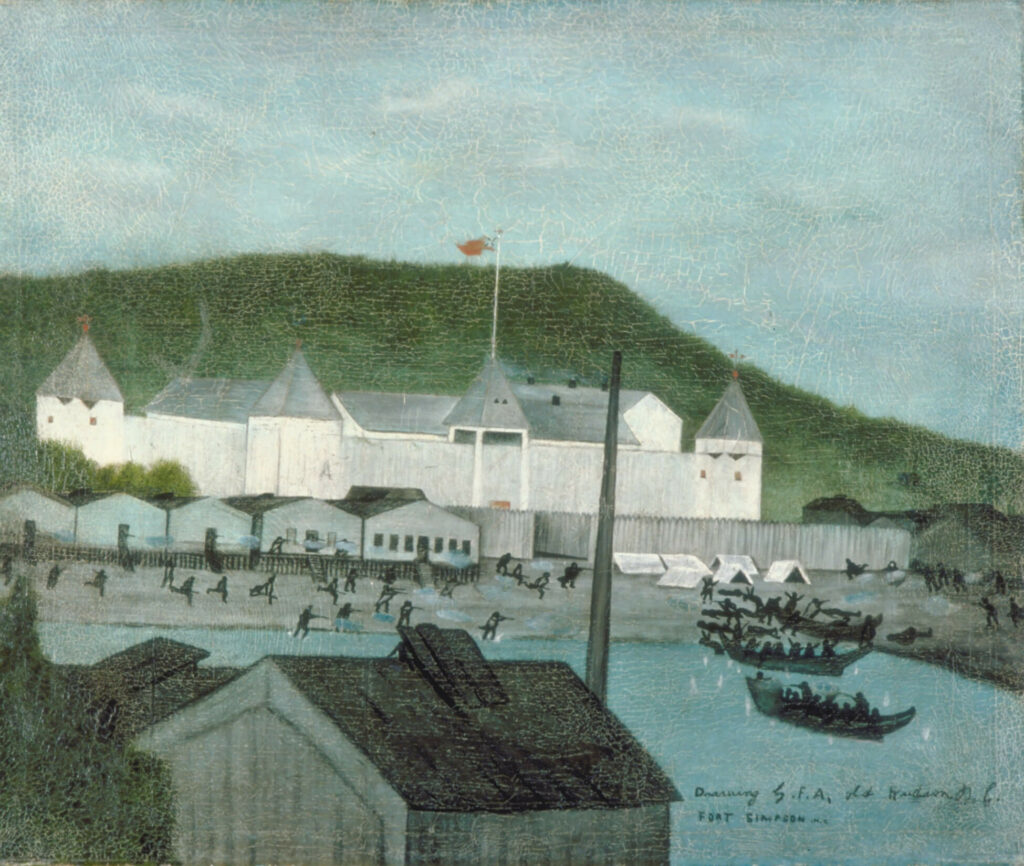

The establishment of British authority in Canada and the expansion of reserves and residential schools coincided with increased European settlement and a burgeoning interest in the stories and artifacts associated with Indigenous peoples in Canada. With the passage of time, some Indigenous artists adopted European forms to tell their own battle stories. The paintings of Frederick Alexcee (c.1857–c.1944) combine his knowledge of past Northwest Coast history, as recounted by storytellers, with his understanding of European art forms. The son of a Tsimshian woman and a Haudenosaunee man, he painted A Fight Between the Haida and Tsimshian, c.1896. The image depicts an 1855 Indigenous battle at Port Simpson, the site on the north-central coast of British Columbia of the Hudson’s Bay Company post of Fort Simpson. Perhaps underlining the power inequality that defined the times, the fort looms dramatically over the Tsimshian and Haida warriors and their few canoes below. Guns are omnipresent in the image, underlining that it was more than painting styles that European settlement brought to Canada.

As the country grew, more monuments were built to foster a sense of nation. In Brantford, Ontario, the city fathers erected the British-designed Joseph Brant Monument, 1886, as a memorial to Thayendanegea, the Kanien’kehá:ka leader who had fought with the British during the American War of Independence. Slowly Canadians began to be employed as sculptors and in monument and memorial construction. The curious Portrait Bust of Techkumthai (Tecumseh), 1896, by Hamilton MacCarthy (1846–1939), portrays General Sir Isaac Brock’s formidable ally in the War of 1812 as a “noble savage”: innately good, uncorrupted by civilization, but clearly “other” in terms of his classical and Indigenous dress. The Maisonneuve Monument, 1893, by Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917), commemorates Paul de Chomedey Maisonneuve, a soldier of France and founder of Montreal.

In the country’s first overseas battle, Canadians volunteered to fight with the British in the South African War (1899–1902), a conflict between British and Dutch settlers in South Africa commonly known as the Boer War. At the time, Canada was still a British dominion and its population largely British subjects. English-speaking Canadians, with their deep ties to what they viewed as the mother country, enlisted enthusiastically—more than 7,000 military personnel participated. Photography documented the conflict from a Canadian perspective—for example, in the image Personnel of Strathcona’s Horse en route to South Africa aboard S.S. Monterey, 1899, showing soldiers crowded together in their itchy wool-serge uniforms somewhere at sea. British artists once again sketched the conflict for reproduction in that nation’s weeklies. One of them was English-born Inglis Sheldon-Williams (1870–1940), later a Canadian First World War artist, who in 1900 drew Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, a successful and popular British commander. Post-conflict, Canadian enthusiasm for the endeavour transformed itself into many war memorials, which still stand today across Canada.

The First World War

The First World War, 1914–18, was an event of epic proportions in Canada’s history. As the country’s first truly national conflict, it involved its entire landmass with the exception of Newfoundland, which until 1949 remained a British colony and therefore fought with the mother country, with bloody consequences. The war began on August 4, 1914, and, as part of the British Empire, Canada was automatically at war as well. More than 600,000 Canadians enlisted, fighting primarily in Belgium and France, and more than 60,000 died. Close to 4,000 of the enlisted were Indigenous, despite being denied the full rights and benefits of citizenship at home.

With few exceptions, English Canadians rallied to Britain’s cause, finding in the conflict a new appreciation of their own identity—a burgeoning nationalism that was cemented with Canadian success at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917. For Canada’s French-speaking population, however, the imposition of military conscription led to deep divisions in the country’s sense of unity. In a more independent post-Confederation world, many French Canadians did not feel this particular British-led conflict needed to involve them.

In addition to the terrible combat and the strong passions it generated, the First World War resulted in a huge output of artistic expression: photography, film, painting, prints, reproductions, illustration, posters, craft, sculpture, and memorials. Artists initiated some of this work themselves, but government and private agencies sponsored the vast majority of it. In doing so they established the concept of the “official” artist or “official” program. This moniker marginalized most artists who could not claim such affiliation, to the detriment of any complete understanding of war art in Canada. It is also important to note that most Canadians saw none of the official paintings, sculptures, or memorials until well after the war’s end, if at all. In consequence, it was mostly photography and the graphic arts in the form of posters, prints, reproductions, and illustrations that informed their wartime visual experiences.

In terms of official art, photography and film were, initially, the visual media the authorities chose to record the events of the First World War. Until 1915, Canadian soldiers were allowed to carry cameras while on active duty, but the apparatus was soon banned for security reasons. In April 1916, Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian head of the Canadian War Records Office (CWRO), persuaded the Canadian War Office to allow official photographers and cinematographers to accompany the forces to the front lines. He was strict about what could be photographed, instructing, “Cover up the Canadians before you photograph them… but don’t bother about the German dead.” The thousands of feet of jerky black and white footage of men, machinery, and horses the cinematographers recorded were incorporated into the film Lest We Forget, 1934.

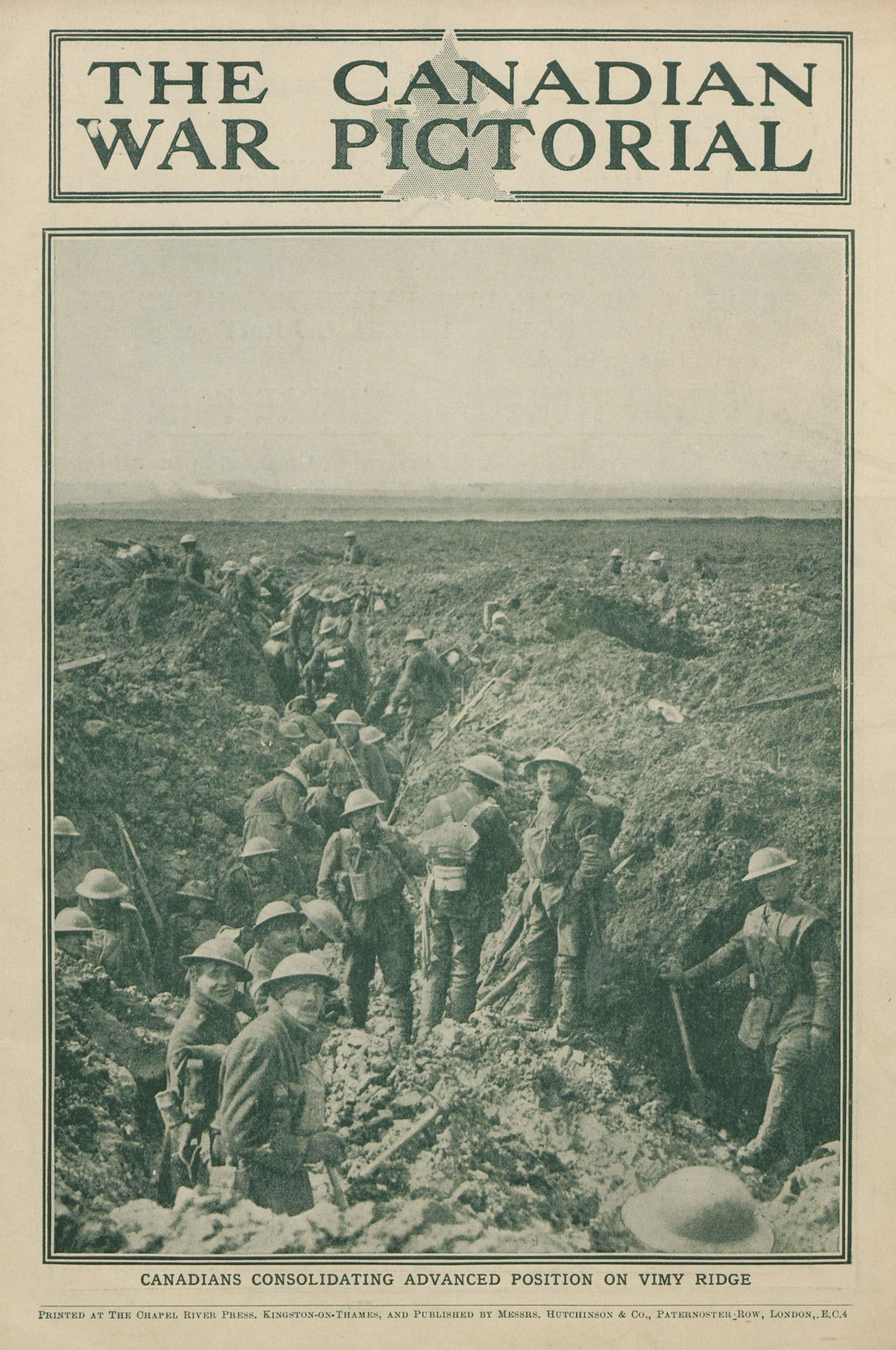

As Canadians were also British subjects, it was not considered important to Beaverbrook’s organization to recruit from Canada. In consequence, Canada’s official cameramen and photographers were all British. Heavy equipment hampered their movements, especially near the front lines. They operated within many restrictions in where they could go and what they could photograph, making it impossible for them to create a complete visual record of the war in Northwestern Europe. While they photographed destroyed buildings and roads turned to mud, there are few corpses or unbandaged wounded soldiers in their images. Yet, thanks to the relatively rapid developing process, the pictures they shot could be quickly reproduced in newspapers, magazines, and books and shown in popular travelling exhibitions. The CWRO used them extensively in the Canadian War Pictorial and the Canadian Daily Record, the latter distributed free to the troops. As painter A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) noted in his autobiography, “the old type of factual painting had been superseded by good photography.”

Painting the war began with a short-lived experiment that saw landscapist Homer Watson (1855–1936) hired by the Canadian authorities to complete three huge canvases of military training in Canada in 1914. The commission was deemed unsuccessful by the government, critics, and the artist. Consequently, painting became a significant medium of record only after the horrific Second Battle of Ypres in April and May 1915, or when it was privately commissioned.

The Ypres engagement saw Canadian forces outnumbered and then decimated by the Germans’ first use of poison gas, resulting in 6,000 Canadian casualties over four days. The recent ban on photographing soldiers in violent situations, combined with the lack of official photographers, ensured that the event was not visually documented. To correct this gap, in November 1916 Beaverbrook used his new official war art program, the Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF), to commission a large painting, The Second Battle of Ypres, 22 April to 25 May 1915, 1917, from English Canadian artist and illustrator Richard Jack (1866–1952). The CWMF was a government-supported British charity that raised money from private sources, publications, and the sale of photographs to commission artists to depict Canadian wartime experiences. Jack’s reconstruction of the battle was loosely based on soldiers’ memories and other first-hand accounts. Soldiers also acted as his models. Beaverbrook was pleased with the result, even though it improbably shows an injured young man standing helmetless while facing the enemy, encouraging the remaining soldiers to fight on. The CWMF decided to commission more artists to record Canada’s war experiences for posterity.

The CWMF program, with close to one thousand artworks, primarily paintings, represents a Canadian first—and it was soon copied by other Allied nations. From December 1916 until 1920 it employed over one hundred artists, a third of them Canadian and the others mainly British, including Paul Nash (1889–1946) and Algernon Talmage (1871–1939). A number of the painters became part of the military as official war artists and were sent to the battlefront to document the activities of specific army units. For instance, British equestrian artist Alfred Munnings (1878–1959) recorded the work of the Canadian Forestry Corps and the Canadian Cavalry Corps.

In Canada, a separate committee associated with the CWMF and run by the National Gallery of Canada commissioned home-front scenes and recommended Canadian artists for overseas duty. Among those who participated were future Group of Seven members A.Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and Frederick Varley (1881–1969), along with sculptor Frances Loring (1887–1968), and painters Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), Henrietta Mabel May (1877–1971), David Milne (1882–1953), and James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924). Of this group, only Jackson, Varley, Cullen, Milne, and Morrice went overseas. No Canadian woman artist was officially sent to the front lines.

Inspired by battlefield experiences, two works that emerged from the program, Jackson’s A Copse, Evening and Varley’s For What?, both 1918, are among the best-known Canadian war paintings of any era. Their images of muddy trenches, blasted trees, and dead bodies vividly evoke the horrors of war. Home-front commissions include May’s Women Making Shells, 1919, and Lismer’s Convoy in Bedford Basin, c.1919, the latter a flotilla of camouflaged vessels and their military escorts in Halifax waters. Art endeavours on both fronts required military cooperation to place artists where they could witness the conflict themselves.

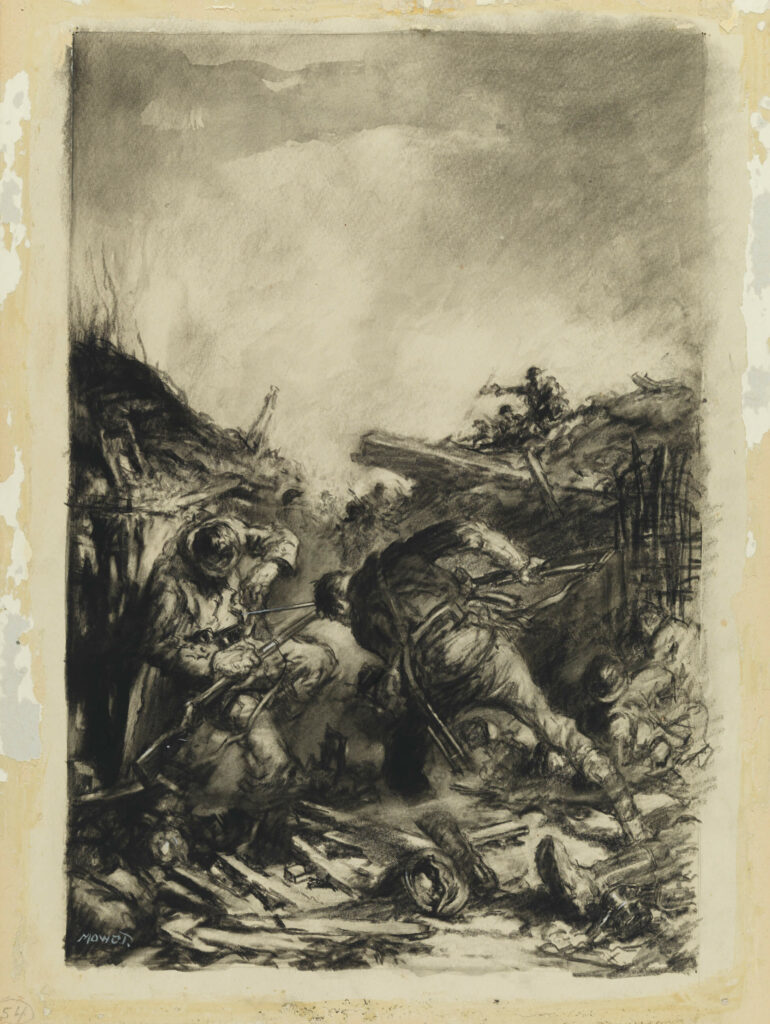

Realizing that graphic art was enjoying a revival in Britain, Canada, and elsewhere, the CWMF commissioned and sold original prints. A list of suggestions in its archives dating from June 1918 includes a proposal for etchings from Cyril Barraud (1877–1965), based on his detailed and decorative but compellingly beautiful field drawings of France and Flanders; reproductions of dramatic action-filled illustrations such as Trench Fight, 1918, by Harold Mowat (1879–1949); and the distribution of two more peaceful existing images by Caroline Armington (1875–1939), in particular No. 8 Canadian General Hospital, 1918.

The list also mentions producing prints from the drawings of ruined towns and devastated landscapes that Gyrth Russell (1892–1970) had made in the field as an official war artist. With the exception of Mowat’s work, all these plans were realized. At the conflict’s end, the CWMF also made reproductions of a number of major painting commissions, such as Jack’s The Second Battle of Ypres, available for sale to raise funds for the official scheme.

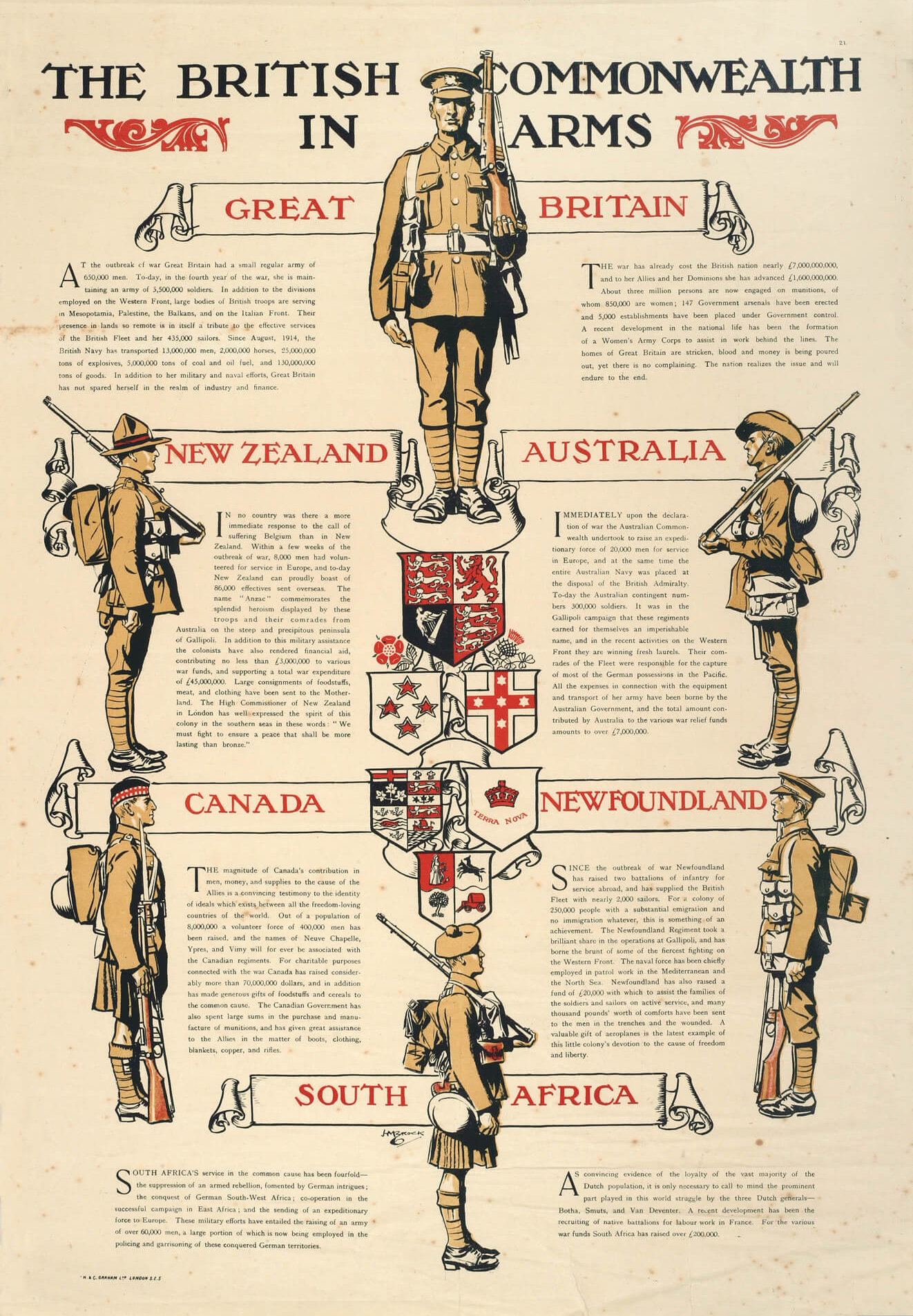

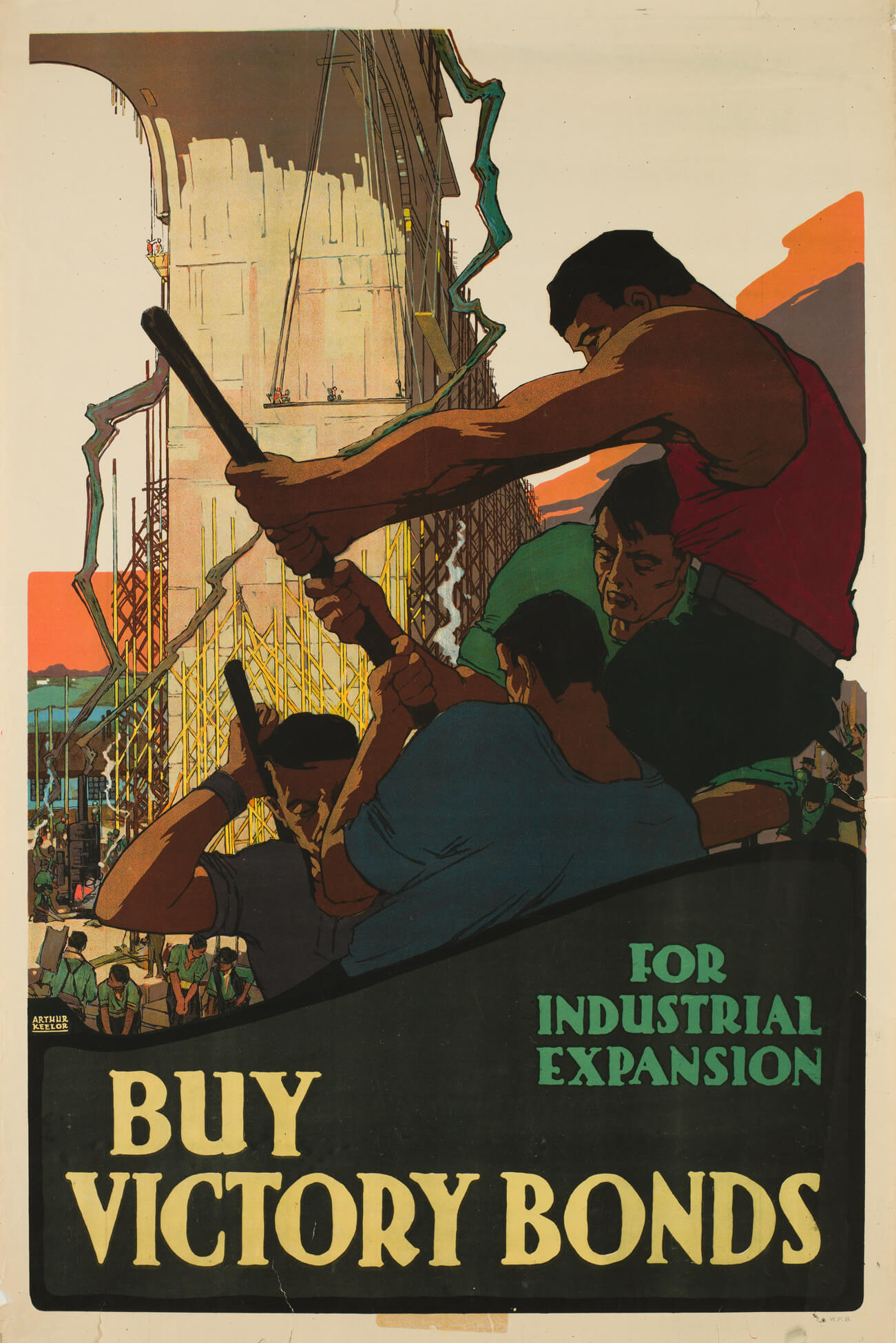

Posters were used by all combatant nations as visual propaganda—to encourage citizens to make sacrifices to avoid defeat and contribute to victory. The authorities produced or commissioned posters to support recruitment, promote military production, inform citizens about proper conduct (such as conserving and preserving food supplies), and assure people that their governments were taking appropriate action. The creators of this material exploited the power of words and images to construct persuasive visual messages that evoked feelings of fear, anger, pride, and patriotism. To standardize propaganda production, in 1916 the Canadian government established the Poster War Service. A photograph of the image-crowded “War Posters” room in the Public Archives building (now Ottawa’s Global Centre for Pluralism) gives some idea of the quantity of propaganda material produced worldwide.

Early design approaches in Canada were often heavily word-based, using simple, descriptive images to convey their messages. Others played on Canada’s self-image and historic iconography to encourage patriotism and sacrifice. Some poster designs acknowledge the modern Western and more revolutionary design approaches emerging at the time, many of which derived inspiration from labour militancy, social (especially urban) reform movements, and various causes on the political left. For Industrial Expansion, Buy Victory Bonds, c.1917, from graphic designer Arthur Keelor (1890–1953), depicts muscular workers building a bridge amid robust lines and bold lettering.

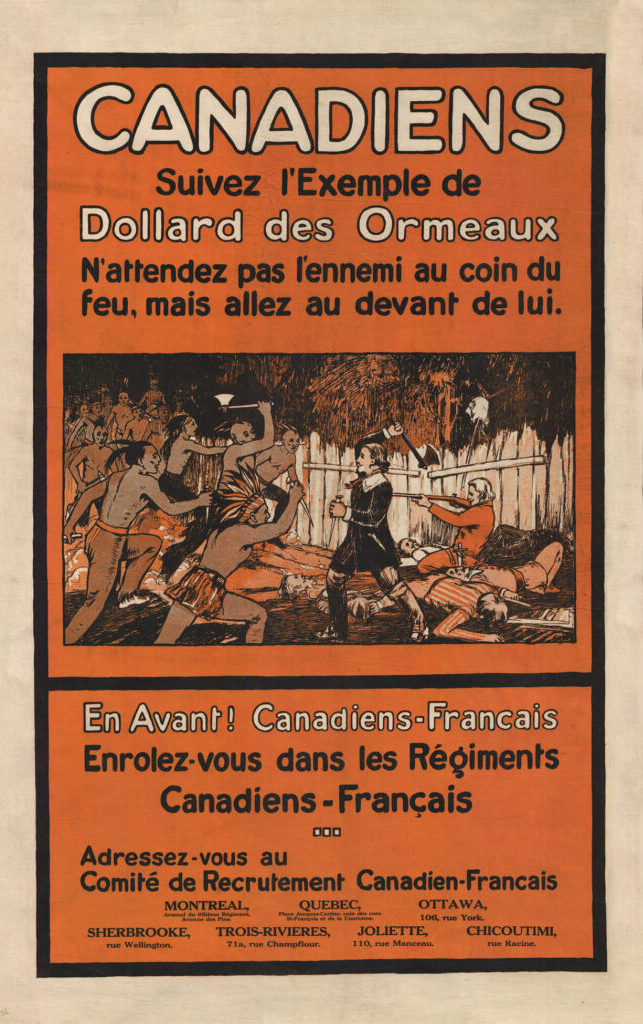

French Canadian recruiting posters reflect Canada’s pressing demand for manpower during the war even as they record the underlying social, cultural, and political strains that affected the country’s war effort and influenced policy. Most French-speaking Canadians did not support Canada’s overseas military commitments to the same degree as English speakers. Some posters invoke French Canada’s martial traditions, while others remind French Canadians of their historic and cultural links with France. All attempted, with markedly little success, to convince them that military service was natural, honourable, and necessary. Canadiens suivez l’exemple de Dollard des Ormeaux, 1915–18, capitalizes on public interest in Dollard des Ormeaux’s famous 1660 stand against the Haudenosaunee, appealing to French Canadians to emulate his exploit. Given that the hero died, however, it is difficult to believe that this poster was effective as a recruitment tool.

Sculpture did not flourish until the First World War was over, often because necessary materials such as bronze were used for other purposes. Toward the end of the conflict, the official war art program employed a few sculptors, but they were usually not Canadians. It proudly acquired a major sculpted modernist frieze, Canadian Phalanx, 1918, from Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović (1883–1962).

Beaverbrook also arranged for a number of British sculptors to work for the CWMF. Clare Sheridan (1885–1970), for example, around 1918 produced a bronze portrait of Canadian air ace Billy Bishop. Controversy, however, surrounds another CWMF British sculptural commission, Canada’s Golgotha, 1918, by leading sculptor Francis Derwent Wood (1871–1926). He depicted the rumoured crucifixion of a Canadian soldier on a Belgian barn door during the 1915 Second Battle of Ypres—a story the Germans denounced postwar as propaganda. The work was promptly put into storage.

Living in Canada, two American-born sculptors, Frances Loring and Florence Wyle (1881–1968), gained recognition when, in 1918, they received an official CWMF commission for fourteen bronze figures of male and female munitions and farm workers. Loring also created a large bronze frieze of factory workers on their lunchtime break, Noon Hour in a Munitions Plant, c.1918–19, and, privately, a moving sculpture of a grieving woman entitled Grief, 1918. These sculptures provide a unique insight into the Canadian home front during the conflict.

Individuals not associated with any official program—the unofficial artists—created much First World War art. As prewar art students, doctors, architects, housepainters, and farm workers, soldier and civilian artists came from markedly different backgrounds. During the war and after, many found the time and the tools to share their experiences visually with their comrades, families, friends, and, sometimes, the authorities. In due course, a number became official Canadian war artists.

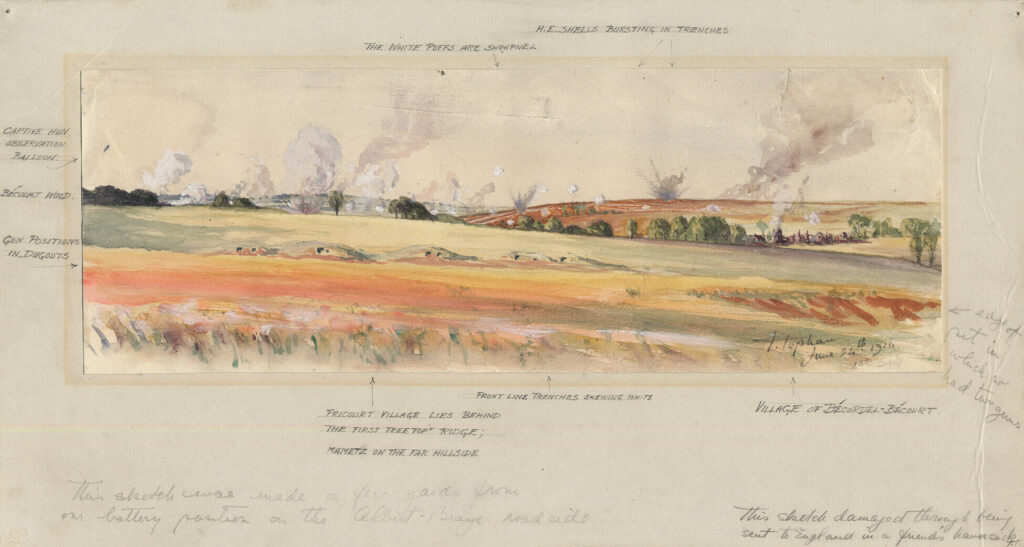

Thurstan Topham (1888–1966), a prewar Scribner’s illustrator, enlisted in the 1st Canadian Siege Battery, where he used his artistic talents to produce observation sketches for military intelligence, such as Opening of the Somme Bombardment, 1916, at the Battle of the Somme. Arthur Nantel (1874–1948) was captured at the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915 and spent the rest of the war in a prisoner of war camp, where, in exchange for food, he painted scenes of life there, such as Christmas Eve in Giessen Camp, 1916. John Humphries (1882–1958) gave his profession as cameraman on his enlistment papers. In 1919 he painted several works directly on the walls of the house in which he was billeted, using colours he had mixed himself from materials he found nearby. After his regiment’s departure, he was told the house had become “a shrine to the Canadians” because of the paintings.

For others, the war inspired later achievements. Swiss Canadian André Biéler (1896–1989) fought and was wounded at Vimy Ridge in 1917. Gassed at Passchendaele, Belgium, later that year, he was transferred for health reasons to the Canadian Corps Topographical Section as a technical illustrator. One rare detailed drawing from this time is Arras, Ruins, 1917. It was in this capacity that he decided he wanted to be an artist after the war—an ambition he achieved with great success as a painter and as a professor of art at Queen’s University, Kingston. Frederick Clemesha (1876–1958) was a member of the “Suicide Battalion,” which had a 91.5 per cent casualty rate. He survived to practise as an architect in Regina and to design the St. Julien Memorial, known as The Brooding Soldier, 1923, which commemorates Canada’s participation in the April–May 1915 Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium.

One artist who was not a soldier but a civilian was Mary Riter Hamilton (1873–1954). She was turned down as an official artist by the CWMF in 1917, but for six impoverished years in the aftermath of battle, almost alone among the graves, she painted in shattered France and Belgium. With its array of ghostly tree trunks massed in a lifeless landscape, her Sanctuary Wood, Flanders, 1920, can be compared with Jackson’s A Copse, Evening, 1918. Hamilton lobbied for years to have her three hundred paintings placed in a national collection but was initially turned down. Eventually, in 1926, Library and Archives Canada agreed to provide a home.

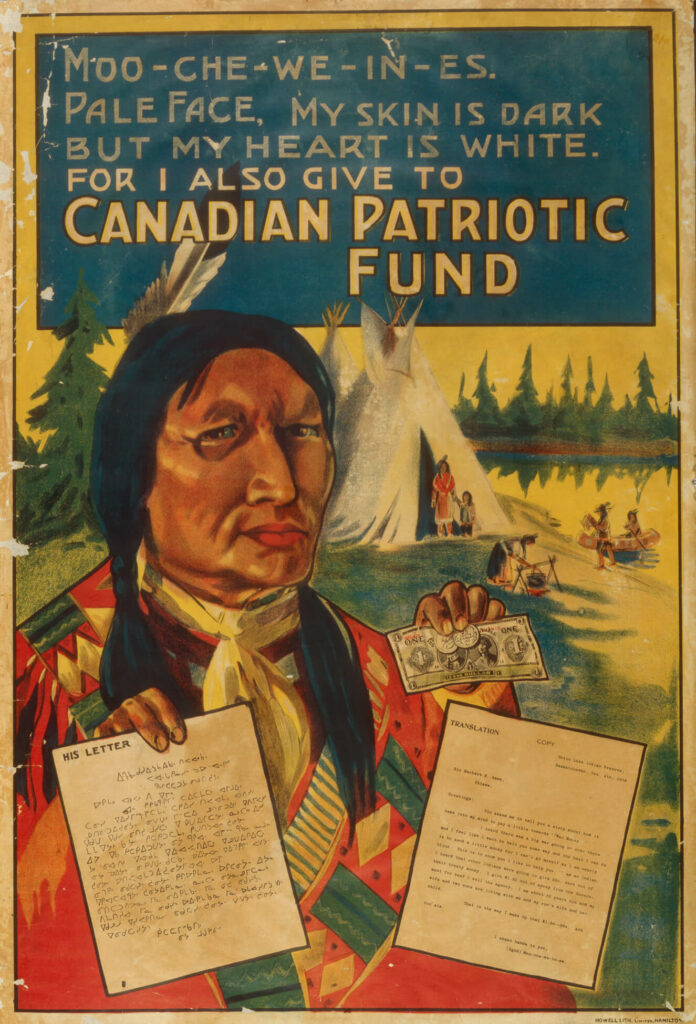

In addition to unofficial artists, various private organizations also supported the wartime arts. Fundraising initiatives such as the Canadian Patriotic Fund commissioned their own poster designs. One by J.E.H. MacDonald, Canada and the Call, 1914, depicts Canada as a woman adorned with patriotic symbols, including the maple leaf and the fleur-de-lis. Egregious to our eyes today, however, is the way Indigenous peoples are portrayed in another Canadian Patriotic Fund poster from 1916, depicting an Indigenous warrior and titled Moo-che-we-in-es. Pale Face, My skin is dark but my heart is white, for I also give to Canadian patriotic fund.

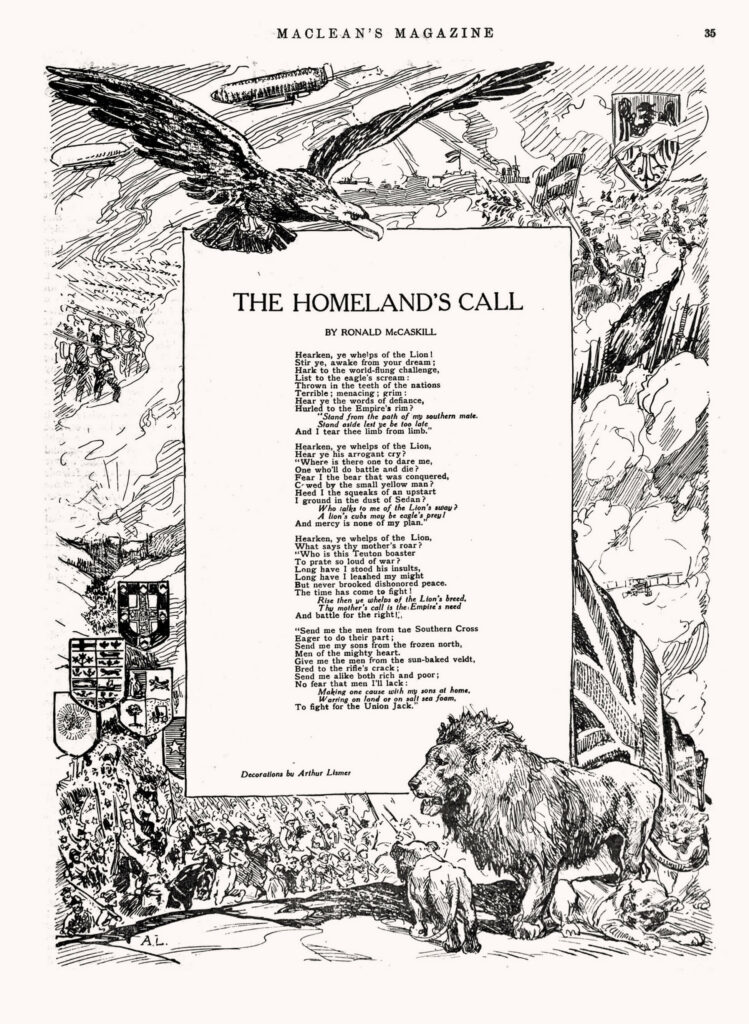

Illustration as a home-front activity thrived as Canada’s small magazine publishing business evolved during the First World War. Maclean’s, for example, was able to employ a number of the commercial artists who later participated in the official war art scheme, including Arthur Lismer. A month after the outbreak of war, Lismer produced for the magazine a stirring collage of patriotic images to illustrate a poem by Ronald McCaskill, “The Homeland’s Call,” 1914.

The Canadian Magazine, a national periodical that appealed to well-educated, well-travelled, and well-heeled readers, published J.E.H. MacDonald’s The Kaiser’s Battle Cry, 1914. The image features the motto “Forward with God” below the German emperor, led by death in the form of a skeleton and with the devil beside him, riding his horse through a devastated corpse-strewn battlefield. Alongside is a satirical poem entitled “The Kaiser’s Latest Ultimatum” by Van de Todd—possibly MacDonald’s nom de plume.

The magazine also supported women artists. Marion Long (1882–1970) provided three touching drawings in 1915, illuminating women’s responses to war: Looking at the War Pictures, featuring a woman and child looking at battle images; Home on Furlough, depicting a woman’s delight at her husband’s return on leave; and Killed in Action, showing a woman reacting to the news of her husband’s death. The masculinized CWMF declined to commission art of this kind.

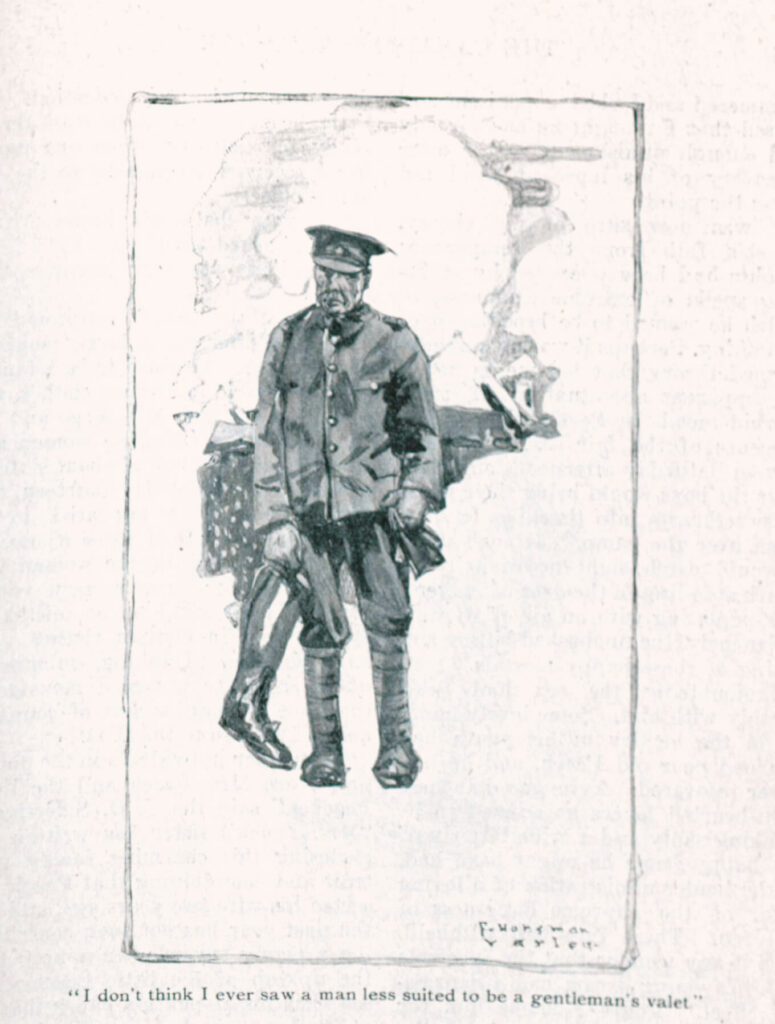

The Canadian Magazine’s December 1918 issue further underlines the difference between the official war art, which the public had yet to see, and what was already viewable in Canada by unofficial artists. Frederick Varley, for example, for most of the war years a little-known commercial artist and painter, illustrated a gentle story of kindness, inadequacy, and deception by First World War veteran and journalist Carlton McNaught. Both illustrations feature the story’s protagonist, a batman (an officer’s servant) named Private Peach. One, in ink and wash, titled I don’t think I ever saw a man less suited to be a gentleman’s valet, depicts him as a single despondent figure, and the other, a line drawing, shows him meekly with the officer he attends. Varley had no overseas experience of conflict when he created these illustrations, but by the time the story was published, he was in London, England, as an official war artist.

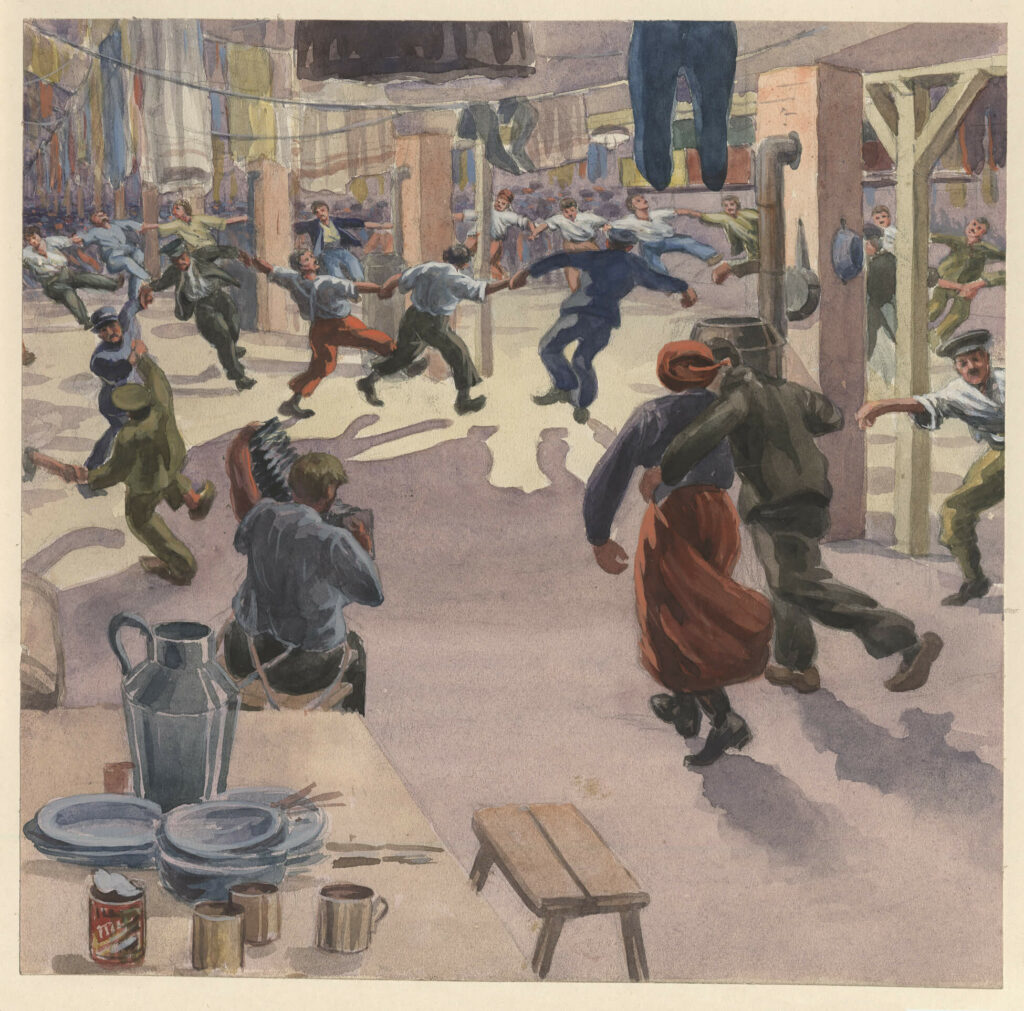

Cartoon publications during the First World War saw foreign cartoonists such as the Belgian Louis Raemaekers (1869–1956) and the Englishman Bruce Bairnsfather (1887–1959) dominating the field. A solitary anonymous cartoon entitled Summer in England, n.d., showing two Canadian soldiers washing their clothes, provides a note of humour in a trying time. Whether it was ever published, we do not know. In 1916 Kenneth Browne (1900–1965) enlisted underage and served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. There he amused his comrades with a regular supply of cartoons that he self-published as Krushing Kaiserism (1918) after the war.

Craft, defined as articles made by hand, reached new heights during and just after the First World War. It is most familiar to us as trench art (items of usefulness or beauty made by soldiers from the detritus of conflict), and as therapeutic embroidery and memorial stained-glass windows. Despite its name, most trench art was not made in trenches but during periods away from the battlefields. Sometimes it functioned as a soldier’s personal souvenir of an important battle, and at other times it was a source of extra cash when sold. In its broadest sense, trench art also includes carvings made by prisoners of war.

For the duration of their service, soldiers were essentially nomadic, moving back and forth between front-line service, leave, convalescence, or imprisonment. In the field they had to be able to carry everything, usually about 27 kilograms of material. Anything non-essential was thrown away. As a result, the artworks they created had to be small, portable, and, preferably, useful. Cigarette cases, for example, were popular. During the war, the German military pioneered the use of aluminum in aircraft. Following crashes, pieces of this light and malleable metal were highly sought after by creative Allied troops on the ground. It could be shaped into a matchbox cover very easily, and Harry Ritz, in one example, scratched his name into the surface. Prisoners of war and internees in Canada similarly made items that they kept as souvenirs or sold when they could to those responsible for their care. An unidentified Austrian prisoner of war created an exquisite cane of wood and metal for a member of Alberta’s Rocky Mountain Rangers. On it, a green metal snake curves sinuously around most of its length, its top in the shape of a dog’s head, its tip a bullet and casing.

The use of occupational therapy with its focus on craft flourished during the First World War. One particularly fine example of the artwork created by shell-shocked soldiers is the flower-strewn altar frontal King George V commissioned for the National Service of Thanksgiving at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, England, in 1919. Altogether, 138 severely injured Australians, Britons, Canadians, and South Africans contributed small sections of embroidered damask, which were then stitched together at the Royal School of Needlework. Canadian soldiers were the first to work on the frontal.

Many cities, towns, and villages commemorated their dead in stained-glass windows in their churches and public buildings. For example, the Welcome Zion Congregational Church in Ottawa erected three commemorative windows in 1922. Designed by the capital’s Colonial Art Glass Company, together they list the names of eight congregation members who died in the conflict. One lists four names under the date 1918. It is richly decorated with Gothic tracery and oak leaves, and the word “freedom” is prominent.

Canada’s most internationally recognized sculptor during and after the war was the American resident and physician Robert Tait McKenzie (1867–1938), who served with the British Royal Army Medical Corps during the conflict. Indeed, he adapted his sculpting skills to assist surgeons in remodelling soldiers’ shell-shattered faces. He completed a number of small, emotionally intense war sculptures, including one posthumous portrait of Canadian Captain Guy Drummond, after April 1915, and Wounded, 1921, as well as some notable figurative war memorials in England, Scotland, and the United States. All these curiously intimate works bear the scars of his personal war experiences. For someone whose medical career before the war had fostered improving the male physique, seeing it mutilated by battle must have been devastating.

The startling wartime sculpture War the Despoiler, 1915, by Canadian Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957), in which a war god tears its victims from the womb of a prostrate female nude, did not find public support at the time and was never cast. Nevertheless, by 1928, in the wake of a significant number of successful postwar memorial commissions, Canadian sculptors including Hahn were able to band together as an exhibiting organization, the Sculptors’ Society of Canada.

War memorial commissions came after the First World War was over. They were challenging for Canadians to obtain in part because so few had the capacity to meet demand. As a result, over half of the memorials in Canada are the product of Italian monument makers. Furthermore, a British sculptor, Vernon March (1891–1930), designed the National War Memorial in Ottawa. In 1925 Hahn won the design for the Winnipeg Cenotaph, but within two years public opinion forced him to withdraw because of his German birth. Eventually, however, Hahn’s war memorial successes outstripped those of all other Canadian sculptors in terms of number.

The most revered Canadian war memorial, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, in France, is by a Canadian-born sculptor, Walter S. Allward (1874–1955). In every line, its twenty allegorical figures powerfully express the country’s overwhelming grief. Their pain-infused poses contrast markedly with the simple architecture in which they are situated, a structure that functions as a site of mourning, much like the dramatic yet minimalist cemeteries that surround the monument. For all its magnificence, however, the monument tells a male story. Even the Welland-Crowland War Memorial, 1939, by Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966), its female protagonist cowering behind the soldier’s heroic posture, fails to diminish the male hegemony that characterizes Canadian First World War memorial sculpture both foreign and homegrown.

The Second World War

Freedom is a word closely associated with the Second World War, 1939–45, which followed only twenty years after the end of the First World War. In the aftermath of 60,000 deaths, hundreds of thousands of wartime injuries both mental and physical, and the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Second World War, although not wanted, was viewed as necessary to ensure freedom from the twin global tyrannies of fascism and dictatorship.

Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, following the German invasion of Poland on September 1. In so doing, it aligned itself with Britain and France in opposing German aggression. Although poorly prepared for war in the wake of the Depression, Canada built up large land, naval, and air forces. The whole country became involved as the critically important industrial and agricultural industries expanded to support the war effort, providing ships, aircraft, training sites, vehicles, weapons, raw materials, and food for the Allied powers. The cost of war was high: of the 1.1 million Canadians who served—10 per cent of the population—42,042 died and 54,414 were wounded.

The arts community was similarly involved, lobbying hard for a war art scheme similar to the CWMF during the First World War. The Canadian War Records, however, was established only at the end of 1942. In contrast, photography was supported from the outset—and Canada’s official war artists were later provided with cameras. Design flourished within sophisticated propaganda programs that included posters and film. Art courses for service personnel were developed and supported, and armed forces art exhibitions and competitions were arranged. Sculpture was notably absent: for the most part, the Second World War provided few new opportunities for memorials, as dates and names were subsequently added to existing memorials.

By the time the war broke out, Indigenous peoples in Canada had endured decades of assimilative practices that helped to erase most of their easily identifiable contributions to the conflict. We know that over three thousand Indigenous people enlisted, but this number excludes thousands of Métis, Inuit, and non-status Indians. Enlisting was challenging. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) required volunteers be “of pure European descent and of the white race” until 1942 and 1943, respectively. In art, notable references to Indigenous culture or creative contributions to the war effort are absent except for the occasional portrait. One egregious independent example by Australian-born Henry Lamb (1886–1963) was titled A Redskin in the Royal Canadian Artillery, 1942. In 1999 the soldier was finally identified and the title changed to Trooper Lloyd George Moore, RCA. Lamb’s Trooper O.G. Govan, 1941, is another rare portrait of a Canadian soldier who was a person of colour.

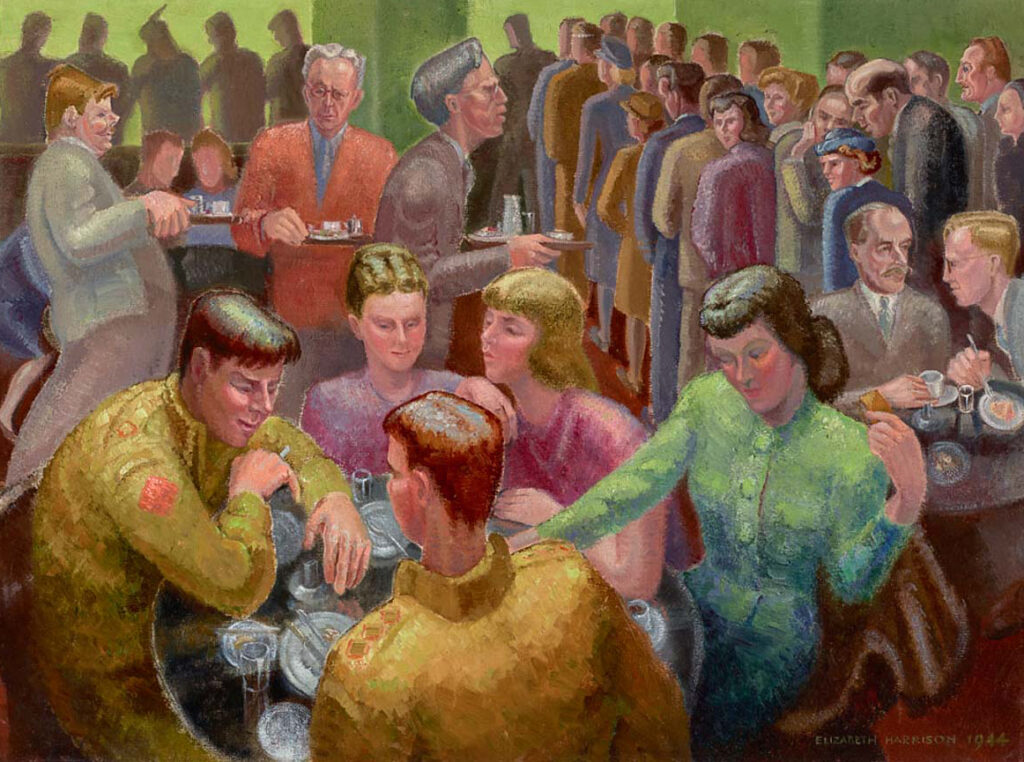

On the home front in Canada, women artists gained considerably more prominence than they had received in previous conflicts. But it was a restricted status. They could support the story of war in Canada, but not overseas. Nevertheless, their contributions are critical to any understanding of the war at home. If government agencies ensured that some were hired to depict the women’s services, it was civilian female artists who guaranteed that the war experience was recorded more thoroughly. Lunchtime, Cafeteria at the Chateau Laurier, Ottawa, 1944, by Elizabeth Harrison (1907–2001), for instance, depicts the interaction of non-uniformed women, men, and soldiers.

Photography and film dominated the official Canadian visual record during the Second World War. The former benefited greatly from the technological developments made since the First World War. During the 1920s, lightweight, rapid-firing cameras such as the Leica (1925) and Rolleiflex (1928) became available for purchase. Moreover, the founding of the National Film Board (NFB) in 1939 played a huge role in fostering Canada’s mushrooming film industry.

Initially, both in Canada and overseas, photography and film were managed separately. The Military Public Relations Group employed photographers, while the Canadian Army Film Unit recorded events with motion-picture cameras. The two organizations merged in 1943 to form the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit, which eventually employed some two hundred individuals. Each branch of the military—army, air force, and navy—appointed its own photographers and cameramen, professionals generally little known today. Usually two cameramen were paired with a photographer, and each unit had a driver and the support of film-developing technicians. Predictably, perhaps, only one photographer was a woman, Karen Hermiston (1916–2007). She photographed Canada’s sole official woman war artist, Molly Lamb Bobak (1920–2014), in London, England, at work on her painting Boat Drill, Emergency Stations, 1945.

The originally modest National Film Board grew exponentially under Scottish film commissioner John Grierson (1898–1972). In 1941 it absorbed the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau and by 1945 it was one of the world’s largest studios, with 750 staff members. During the war, it released more than five hundred films, including the Canada Carries On series produced by Jane Marsh Beveridge (1915–1998). Sensitive to the challenges women were facing during the war to break away from their traditional domestic roles, she directed Women Are Warriors, 1942, Proudly She Marches, 1943, and Wings on Her Shoulder, 1943. She resigned from the NFB in 1944, when Grierson refused to put her formally in charge of the Canada Carries On series because she was a woman.

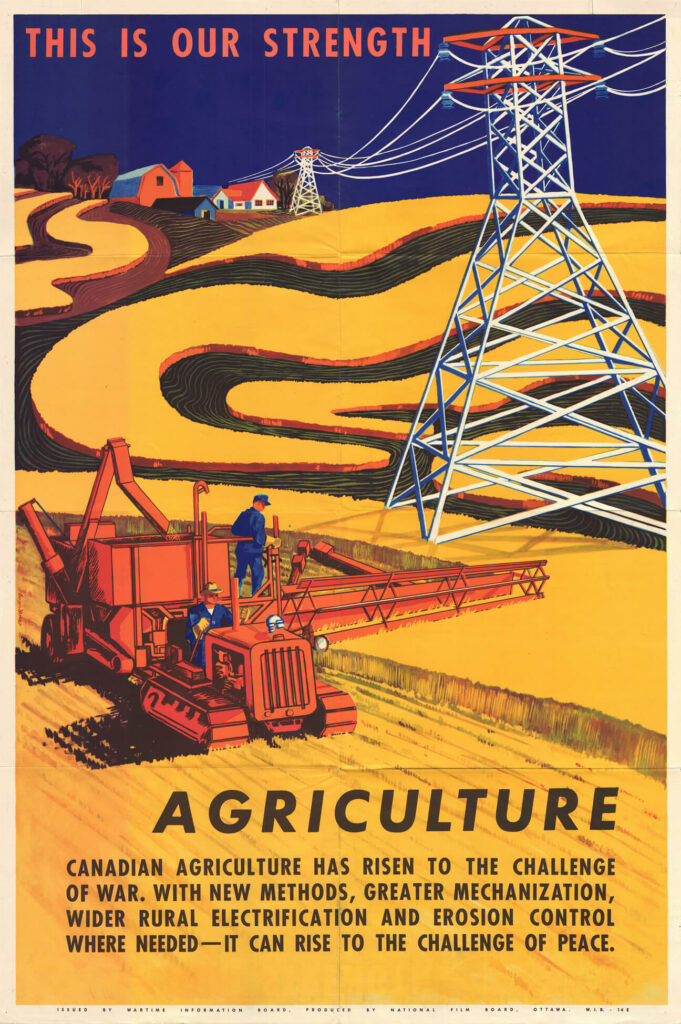

Posters were ubiquitous during the Second World War—many artists were involved in poster production throughout the conflict. Albert Cloutier (1902–1965), who later became an official war artist, was the government supervisor for war poster production from 1940 to 1944. In the early years, National Gallery of Canada director H.O. McCurry (1889–1964) was active in poster-design management and keen to employ Canadian artists. The National Film Board hired many Canadian designers— Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), for example, created the food production poster This Is Our Strength – Agriculture, n.d.

Recruiting was, perhaps, the most critical theme in poster design. Two images by Canadian artists show how historic acts of heroism were harnessed to present-day circumstances to persuade people to enlist. One by Eric Aldwinckle (1909–1980) (later an official war artist) entitled Canada’s New Army Needs Men Like You, c.1941–42, shows a soldier on a rearing motorcycle before the ghostly image of a medieval knight on a leaping horse. Another, by Gordon K. Odell (1898–1981), The Spirit of Canada’s Women, 1942, places several lines of marching women soldiers in front of a spectral image of the medieval French heroine Joan of Arc.

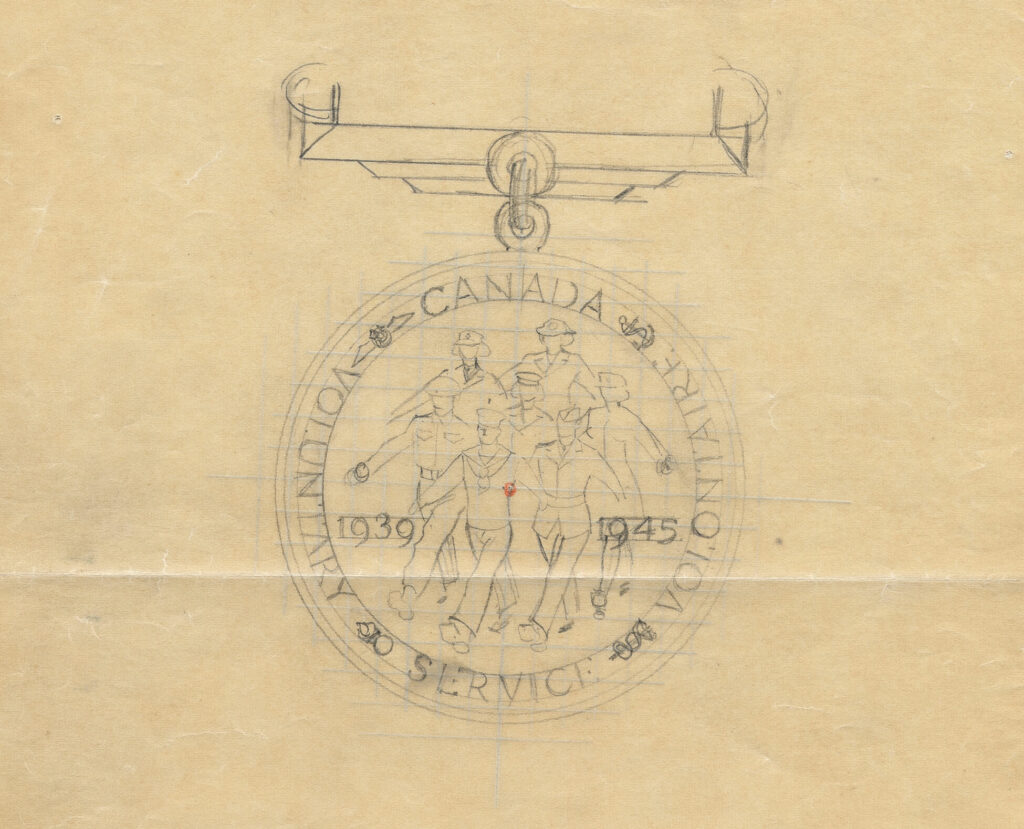

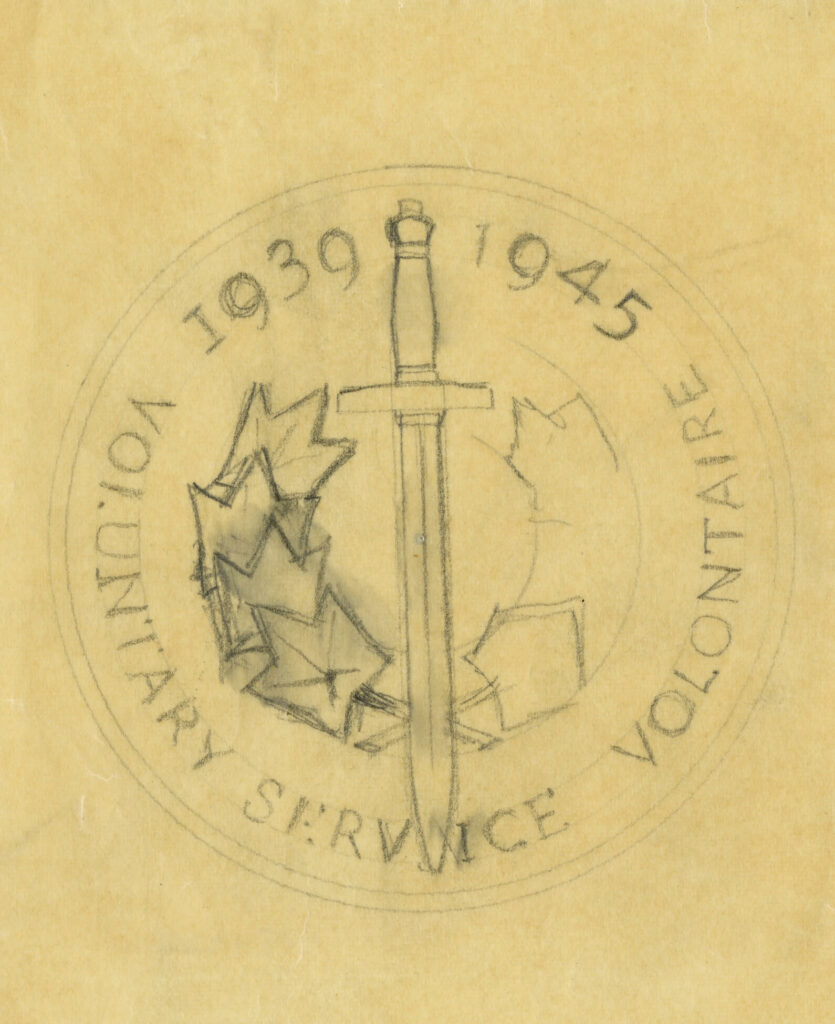

During the Second World War, painting dominated Canada’s official war art program, the Canadian War Records, which, as a collection, includes approximately 5,000 small paintings that depict events, locations, machinery, and military personnel on both the battle and the home fronts. A.Y. Jackson was heavily involved in getting the program started and retained a consultative role in recommending which artists should be commissioned. Charles Comfort (1900–1994) was responsible for identifying the materials the artists should receive but also went overseas himself as an official army war artist. Before he did, however, he designed Canada’s only home-grown Second World War medal—the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, first presented in 1943, showing a group of uniformed men and women marching forward together. The authorities awarded a total of 650,000 of these medals.

The thirty-two official war artists employed—all officers—included Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001), Miller Brittain (1912–1968), Bruno Bobak (1923–2012), Alex Colville (1920–2013), and Jack Nichols (1921–2009). Divided among the three services—army, navy, and air force—and serving in all the Western theatres of war, including Britain, Italy, Northwest Europe, and the Atlantic Ocean, they were given both directions and supplies. The artists’ assignments, which usually saw them embedded with designated army units, ships, and air force squadrons, closely resembled those of their First World War predecessors. Their official instructions specified the quantity of art to be produced, the size of artworks, and the subjects, leaving some room for interpretation. Because civilian artists faced severe shortages of materials such as paper, a number joined official programs simply to get more plentiful supplies.

Most artists, steeped in landscape, still life, or portrait painting, had little preparation for war subject matter. Accuracy was paramount, and many participants prepared dozens of small, detailed sketches of equipment, uniforms, and vehicles before they completed their well-received canvases, which were widely exhibited. As a result, a great deal of the official art is illustrative in nature. If it had reflected contemporary art approaches such as abstraction, the authorities likely would have rejected it. The romantic aircraft painting Per Ardua Ad Astra [Through adversity to the stars], 1943, by Carl Schaefer (1903–1995), for example, was initially spurned because they thought the aircraft depicted, a climbing clipped-wing Spitfire Mk.IX skidding to starboard, was not sufficiently identifiable.

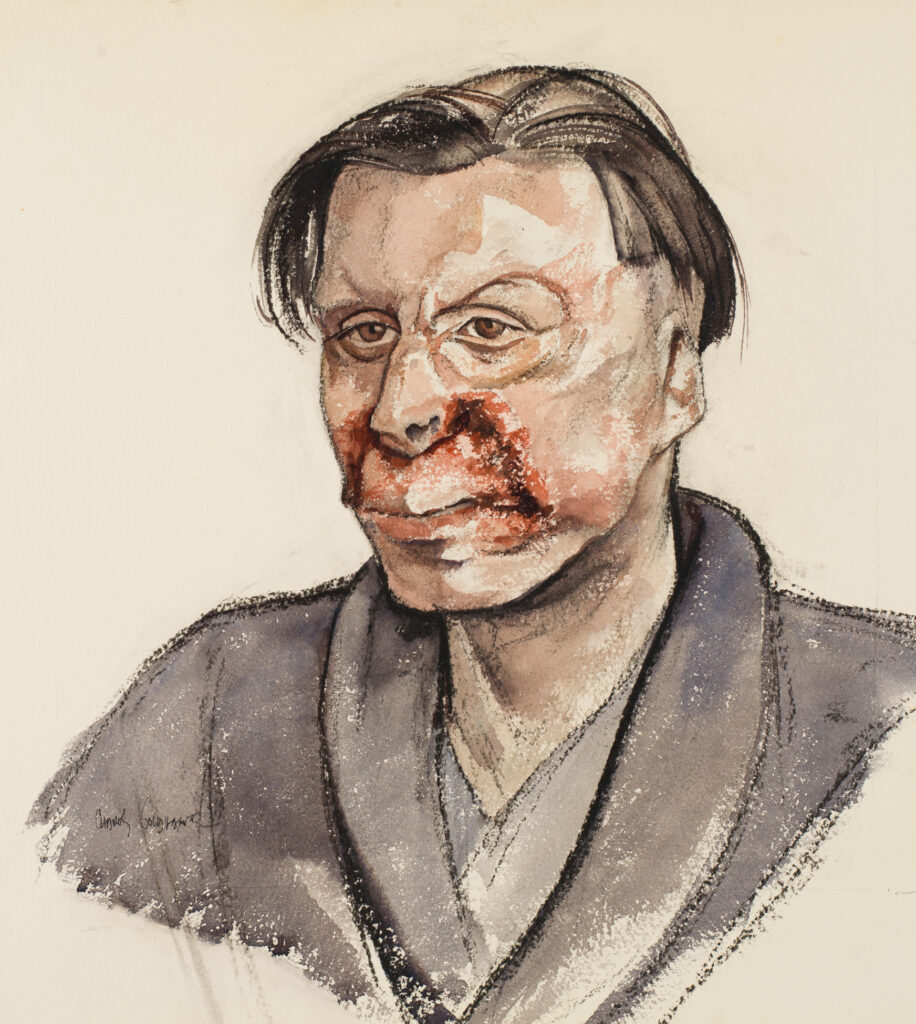

In contrast to the First World War, when drawings often survived only as precursors to finished paintings, during the Second World War, Canadian War Records works on paper were frequently considered finished artworks. Charles Goldhamer (1903–1985), for example, enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1943 as a supervisor of art programs for air force personnel before his appointment as an official war artist. In this capacity, he sketched badly injured pilots and aircrew at the Royal Canadian Air Force’s advanced plastic surgery unit at East Grinstead, West Sussex, England, where a Canadian, Albert Ross Tilley, was one of the pioneering surgeons. Face Burns, Sgt. James F. Gourley, RAF, 536215, 1945, portrays a Royal Air Force sergeant who underwent thirty-seven operations at the unit.

The only woman official war artist employed by the Canadian War Records was Molly Lamb Bobak, formerly a private in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC), who travelled overseas after the war in Europe ended in May 1945 (she married Bruno Bobak that December). Her long record of military service in Canada, formal art education, and friendship with A.Y. Jackson all helped to ensure her commission. One of her notable works is the mistitled Private Roy, 1946, a mesmerizing portrait of a black Canadian woman working behind an army canteen counter. Sergeant Eva May Roy of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps was one of a small number of black enlistees in this service. In referring to her as a private in her portrait, Bobak effectively demoted her.

Charged with documenting the war in paintings, the Canadian War Records artists occasionally slipped the bonds of military activity to focus on more human subjects. Craft was an important part of soldiers’ rehabilitation programs, as the painting R.C.A.[F.] Officer Doing Handicraft Therapy, No. 1 Canadian General Hospital, Taplow, England, 1945, by official war artist George Campbell Tinning (1910–1996) demonstrates.

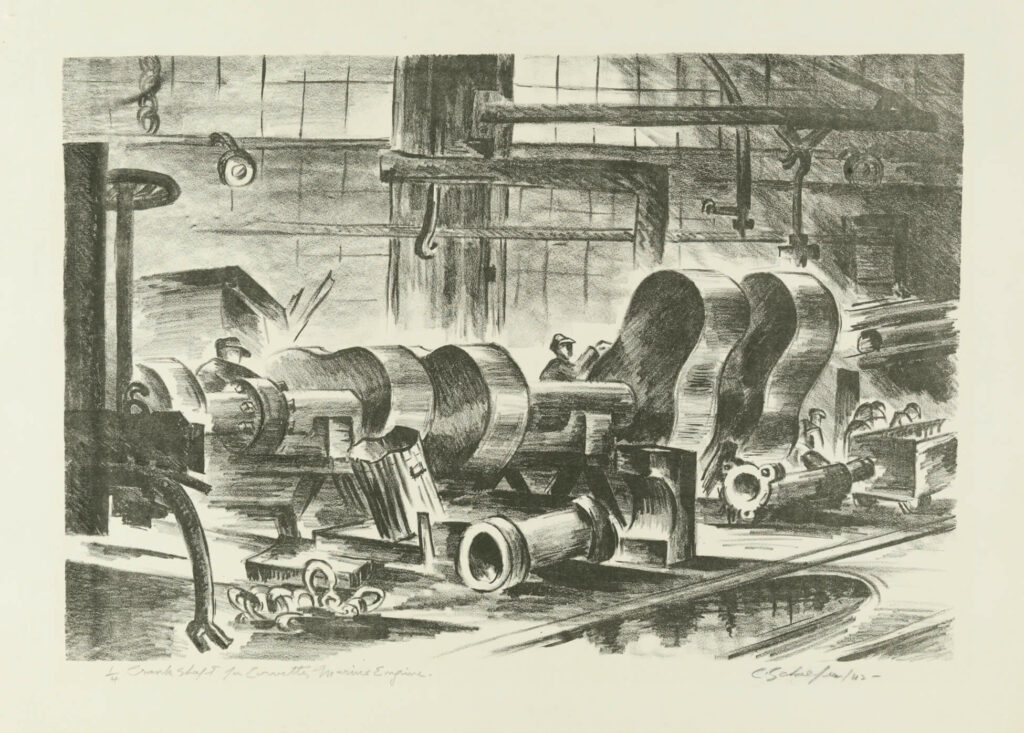

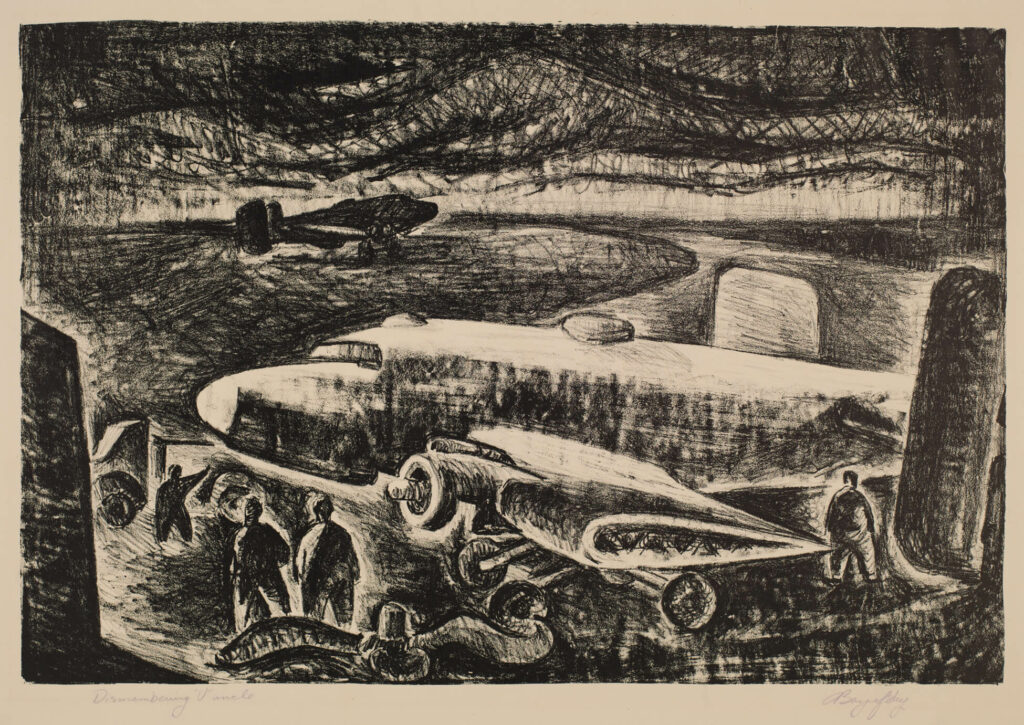

The original artist prints that had been such a feature of the First World War program—lithographs, etchings, and drypoints—were seldom made during the Second World War. Of two examples that are known, the lithograph Crankshaft for Corvette, Marine Engine, 1942, by official war artist Carl Schaefer resulted from an earlier opportunity to draw in the John Inglis manufacturing plant in Toronto. The other print, a battlefield image by Aba Bayefsky titled Dismembering U Uncle, c.1943–45, was based on a drawing of the same name showing an air force crew taking apart an aircraft.

As for unofficial art, during their sometimes extensive periods of non-activity, soldiers were encouraged to paint and exhibit to foster a sense of team spirit and to allay boredom. The first Canadian Armed Forces Art Exhibition opened in Toronto in 1942, later touring to eight army camps. There was another display in 1944 and a final one in 1945. Beulah Jaenicke Rosen (1918–2018) of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps exhibited her lively Ottawa restaurant scene, Eat Early in Comfort, 1943, in the 1944 exhibition, one of only five women exhibitors out of a total of thirty-three artists. Before she was officially commissioned, Molly Lamb Bobak painted the first-night crowd of uniformed service personnel and well-dressed civilians in Opening Night of the Canadian Army Art Exhibition, 1944. The RCAF also organized exhibitions. Future Painters Eleven artist Tom Hodgson (1924–2006) exhibited First Flight, 1944, in the Royal Canadian Air Force Art Exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada and, later that same year, saw it tour Canada. Textile designer and soldier artist George Broomfield (1906–1992) exhibited his war art with the Ontario Society of Artists in its 1943 and 1944 annual exhibitions.

For most soldier artists who exhibited during the war, postwar recognition of their artistic contributions was slow compared to that of the Canadian War Records artists. Broomfield offered his watercolour paintings to the National Gallery of Canada, which eventually accepted them just before the transfer of all the war art to the Canadian War Museum in 1971. The Canadian War Museum acquired Hodgson’s war art in 1997, and Rosen’s only in 2006. Some artists were unable to paint their wartime experiences until many years had passed, making the institutional acquisition of their work later still. As a result of art therapy at his seniors’ residence, Richard Coady (b.1921) painted some challenging wartime memories, such as D-Day Landing, Normandy, only in 1992. The Canadian War Museum subsequently acquired the painting.

Civilian women artists contributed to recording the war on the home front when the National Gallery of Canada commissioned art from several of them in 1944 and 1945. Director H.O. McCurry was concerned that the work of Canadian servicewomen in Canada was not being captured in paint. Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986), Alma Duncan (1917–2004), Bobs Coghill Haworth (1900–1988), and Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949) all rose to the challenge and produced significant paintings.

With two lengthy commissions in 1944 and 1945, Nicol MacLeod produced close to one hundred compositions in watercolour and oil focused on women and war. Brash and colourful work such as Morning Parade, 1944, represents a record of the 17,000 women who served in the Royal Canadian Air Force (Women’s Division), the 21,600 who served in the CWAC, and the 7,000 who served in the Royal Canadian Navy. Different in style from the work of most of her contemporaries, Nicol MacLeod’s art often depicted Canada’s servicewomen cleaning, cooking, and washing up as well as participating in drills and parades.

New Canadians also drew on their war experiences, but the work of many of them remains entirely unknown. Subject matter and personal proactivity have determined much of what has been collected. The anti-war drawing War Torn, 1943, by German-born NFB poster designer Fritz Brandtner—a powerful but imagined image of a violent bombing raid—is one example. Brandtner immigrated to Canada after the First World War well-tutored in Expressionist and Cubist styles.

In the twenty years between the two world wars, substantial changes occurred in the graphic art world. Photography, for example, drastically shrank the need for illustrators, whose work diminished until after the conflict. Molly Lamb Bobak’s illustrated war diary, W110278: The Personal War Records of Private Lamb, M., documents her life in the Canadian Army between 1942 and 1945. It was little known until published in full in 1992. The first page, Girl Takes Drastic Step!, 1942, shows the young recruit in uniform in the rain, perhaps a subtle indication of her initial ambivalence about joining up.

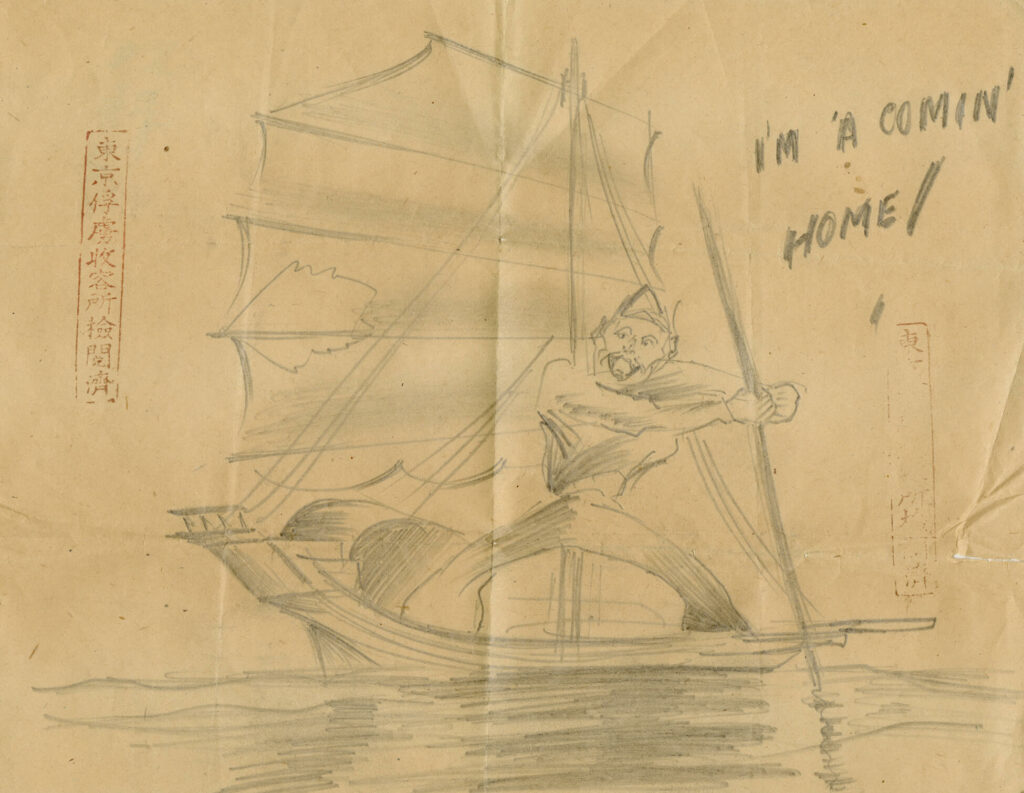

The prisoner of war experiences of William Allister (1919–2008) drew attention only because of his postwar willingness to share them with others, as in the 1995 Canadian documentary film The Art of Compassion. Imprisoned by the Japanese after the 1941 Battle of Hong Kong, he managed to pilfer enough materials from his captors to keep a sketchbook and diary and make paintings, most of which are no longer extant. One surviving drawing, I’m ‘A Comin’ Home!, c.1945, expresses his joy at the prospect of release. It depicts a soldier with a huge grin on his face rowing a small junk (a traditional Chinese sailing vessel).

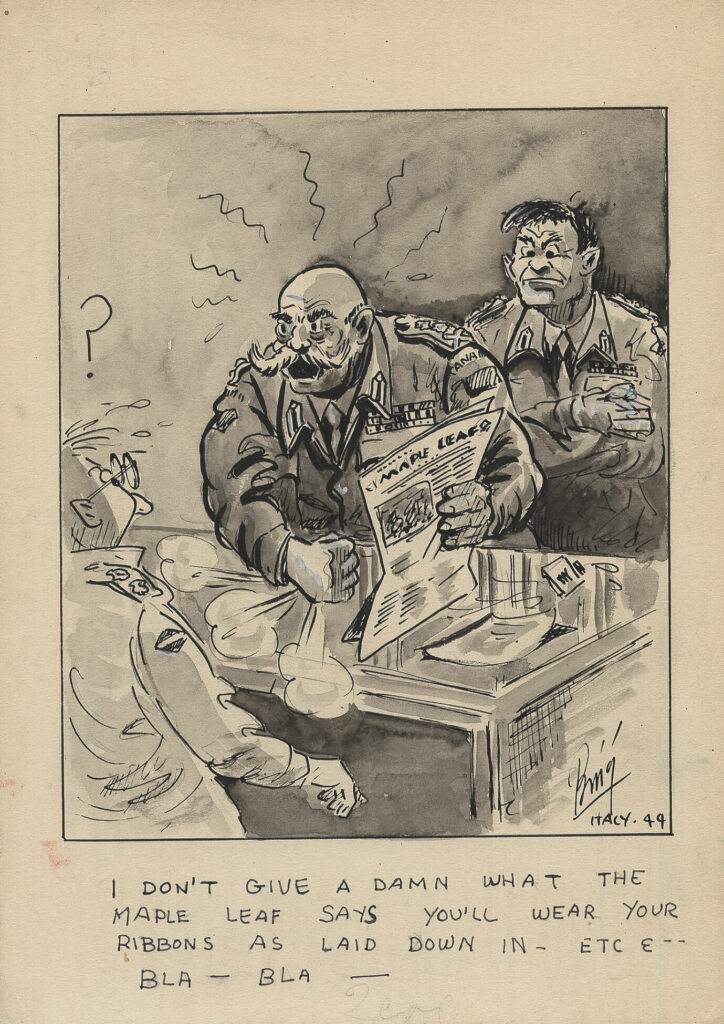

Cartoonists, in contrast, made their reputations in wartime. A soldier first and an artist second, Bing Coughlin (1905–1991) was the most prominent of a small group of professional Canadian cartoonists that included Toronto Star artist Les Callan (1905–1986). The soldiers’ newspaper, The Maple Leaf, published the trials and tribulations of Coughlin’s character “Herbie,” as exemplified in I don’t give a damn what the Maple Leaf says, 1944. Another of The Maple Leaf’s occasional cartoonists, soldier Thomas Luzny (1924–1997), became a muralist after the war, although his cartooning background always showed through. Humanity in the Beginning of the Atomic Era, 1953, with its terrifying white death’s head emerging from a nuclear explosion, tells us of the future tragedies he imagined would follow the conflict.

Artwork reproductions also took on a new significance in artists’ lives during the conflict. H.O. McCurry responded to A.Y. Jackson’s suggestion that the National Gallery support the reproduction of Canadian artists’ work for distribution to armed forces bases in Canada and overseas. Both men believed that the prints would provide remuneration for low-income artists who had not been selected as official war artists. The distribution was impressive: 1,781 prints to the Royal Canadian Navy, 3,000 to the Canadian Army, 3,000 to the Royal Canadian Air Force, and 2,727 to the auxiliary services. The only image to stray from the generally bucolic peacetime imagery of the series was Halifax Harbour (North and Barrington Streets), c.1944, by Leonard Brooks (1911–2011), husband of celebrated Canadian photographer Reva Brooks (1913–2004). In this instance, Brooks was also an official artist attached to the navy.

The work of civilian photographers augmented the precedent set during the First World War for photograph-saturated newspaper and magazine articles that met public and propaganda needs. One of the first memorable civilian photographs from the war is Wait for Me, Daddy, an image taken by American-born Claude Dettloff (1899–1978) on October 1, 1940, which shows the British Columbia Regiment marching down a street in New Westminster. While Dettloff was preparing to take the photo for a local newspaper, young Warren ran away from his mother to his father, Private Jack Bernard, who was in the parade. The picture received extensive exposure and was used in war-bond drives to raise money for the conflict. For the public, it spoke of family values, the importance of enlisting, and the necessity of fighting the war to preserve families.

One of the better-known civilian photographers was Turkish Canadian Malak Karsh (1915–2001) (brother of Yousef Karsh [1908–2002]). Early in 1946, as the Exhibition of Canadian War Art was about to open at the National Gallery of Canada, the authorities hired the younger Karsh to photograph many of Canada’s official war artists surrounded by their paintings and sketches. Clearly, images of the paintings themselves were not considered sufficient for publicity purposes. Karsh’s photograph of Alex Colville painting Infantry, Near Nijmegen, Holland, 1946, surrounded by sketches, excludes Colville’s own personal reliance on photography. Inspiration for this painting arguably lay not in sketches as much as in a British-distributed Second World War photograph.

Sculpture was virtually invisible during the Second World War. Despite the promise for the development of Canadian sculpture after the First World War, the sculptural record between 1939 and 1945 is thin owing to the absence of memorial work. Freedom from Want, 1944, by Violet Gillett (1898–1996), a moving portrayal of a woman cradling her sleeping child—clearly inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 speech on the four freedoms the United States was defending by entering the war—was never cast. Personal friendship motivated Florence Wyle to produce a bronze bas-relief of official war artist Charles Comfort in uniform when he was home on leave in early 1945. Her life partner and fellow sculptor Frances Loring contented herself with writing, compiling a small, undated publication for soldiers with spare time: How to Get Started: Woodcarving for Pleasure.

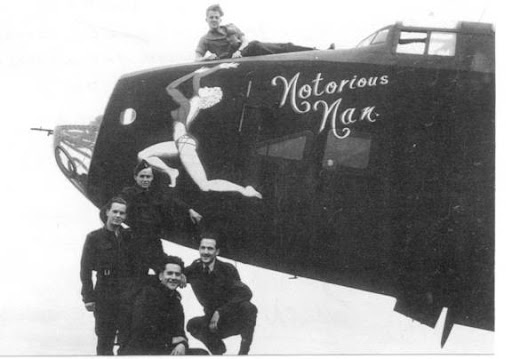

As in the First World War, soldiers and civilians again produced quantities of so-called trench art, souvenir crafts made, most commonly, from metal battlefield litter, as personal memorabilia. Following demobilization in 1945, sculptor Joe Rosenthal (1921–2018) transformed a wooden gun butt into an untitled figurative carving. Incarcerated as a prisoner of war in Sham Shui Po Camp in Japanese-captured Hong Kong, Canadian civilian R.P. Dunlop (dates unknown) carved a number of items out of local bamboo, including a pipe decorated with a maple leaf. “Nose art,” usually cartoons painted on aircraft, is perhaps the most recognizable form of trench art to emerge during the Second World War, as exemplified in Fangs of Fire, 1944–45, by Floyd Rutledge (1922–2006).

Remembering the Holocaust

During the Second World War, few of the official artists were aware of the Holocaust (when Nazi Germany and its collaborators organized the killing of six million Jews and millions of others) taking place around them in Europe, and fewer still had access to the death camps after they were liberated. Aba Bayefsky was a twenty-two-year-old Jewish official war artist attached to the Royal Canadian Air Force when he depicted the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen in 1945. Two other official war artists, Alex Colville and Donald Anderson (1920–2009), also visited this German concentration camp shortly after its liberation by the British. Colville’s work from Bergen-Belsen, his elegiac Bodies in a Grave, 1946, is the best-known image from this tragic place.

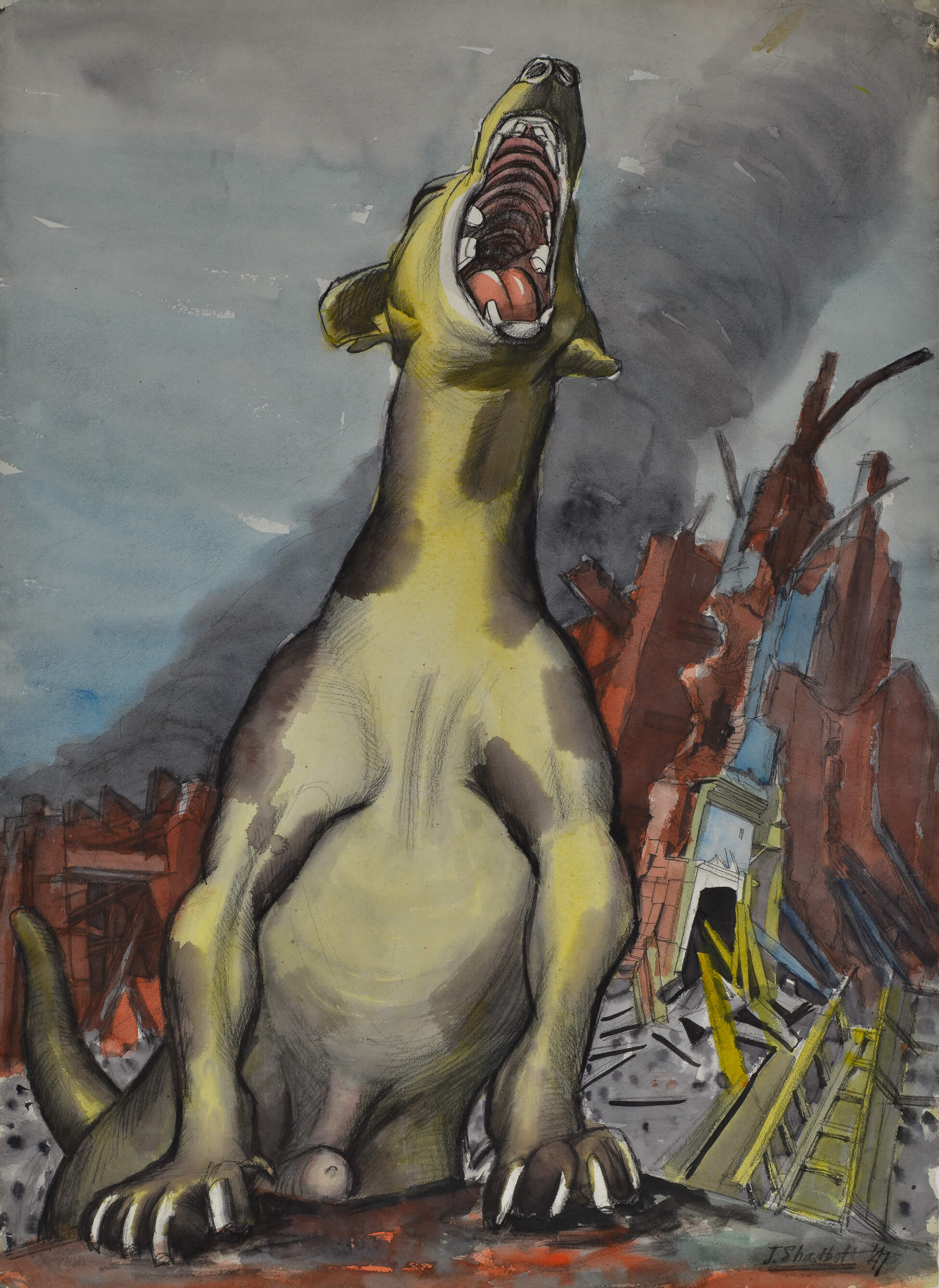

The Holocaust looms large in the aftermath of the Second World War despite minimal official artistic attention being paid to it during the conflict. After it ended, information on the horrific and unprecedented number of killings gradually became more widespread, and artists, both Jewish and gentile, soldier and civilian, responded to its tragic imagery, as seen in film and photography. Following the war, Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) was tasked in London with sorting the pictures taken by members of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals at the Nazi concentration camps of Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald. He expressed the horror he experienced in a series of artworks he began in 1946 after his return to Canada. Compositions such as Dog Among the Ruins, 1947, where a hound, jaw agape, howls in front of ruined buildings, visually attest to his profound anger at the appalling human and physical legacies of this conflict.

Another notable immediate postwar example is Gershon Iskowitz (1920/21–1988), who, after surviving the German concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald, came to Canada in 1949. He drew what happened to him at the time using found materials. Condemned, c.1944–46, a portrait of a man whose fate is likely death, judging by the black shadow behind his head, is one such moving example. Iskowitz subsequently went on to enjoy a stellar career as a Canadian artist.

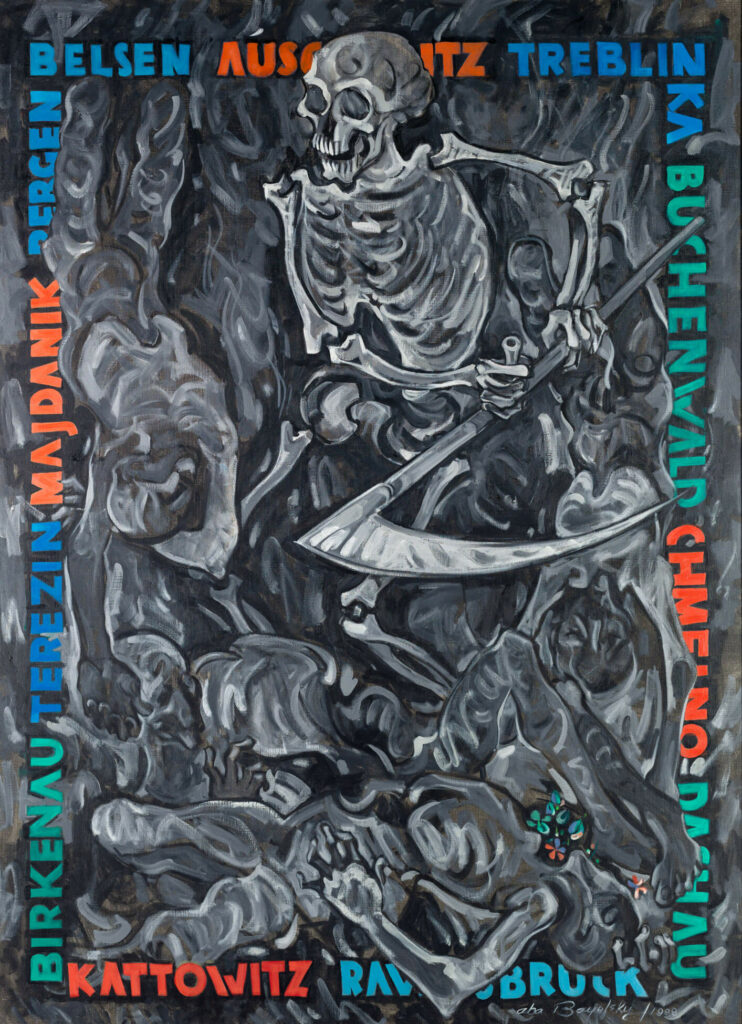

Postwar Holocaust compositions by Aba Bayefsky came much later but clearly demonstrate the immense impact that personal exposure to its horrors as a war artist continued to have on him. Remembering the Holocaust, 1988, comprising the monochromatic figure of the Grim Reaper and the mutilated bodies that form his crop, is framed by the names of the major concentration camps of the Second World War. Flame-like forms rise behind the murderous creature, while the whole scene is convulsed with terrifying frenzied activity.

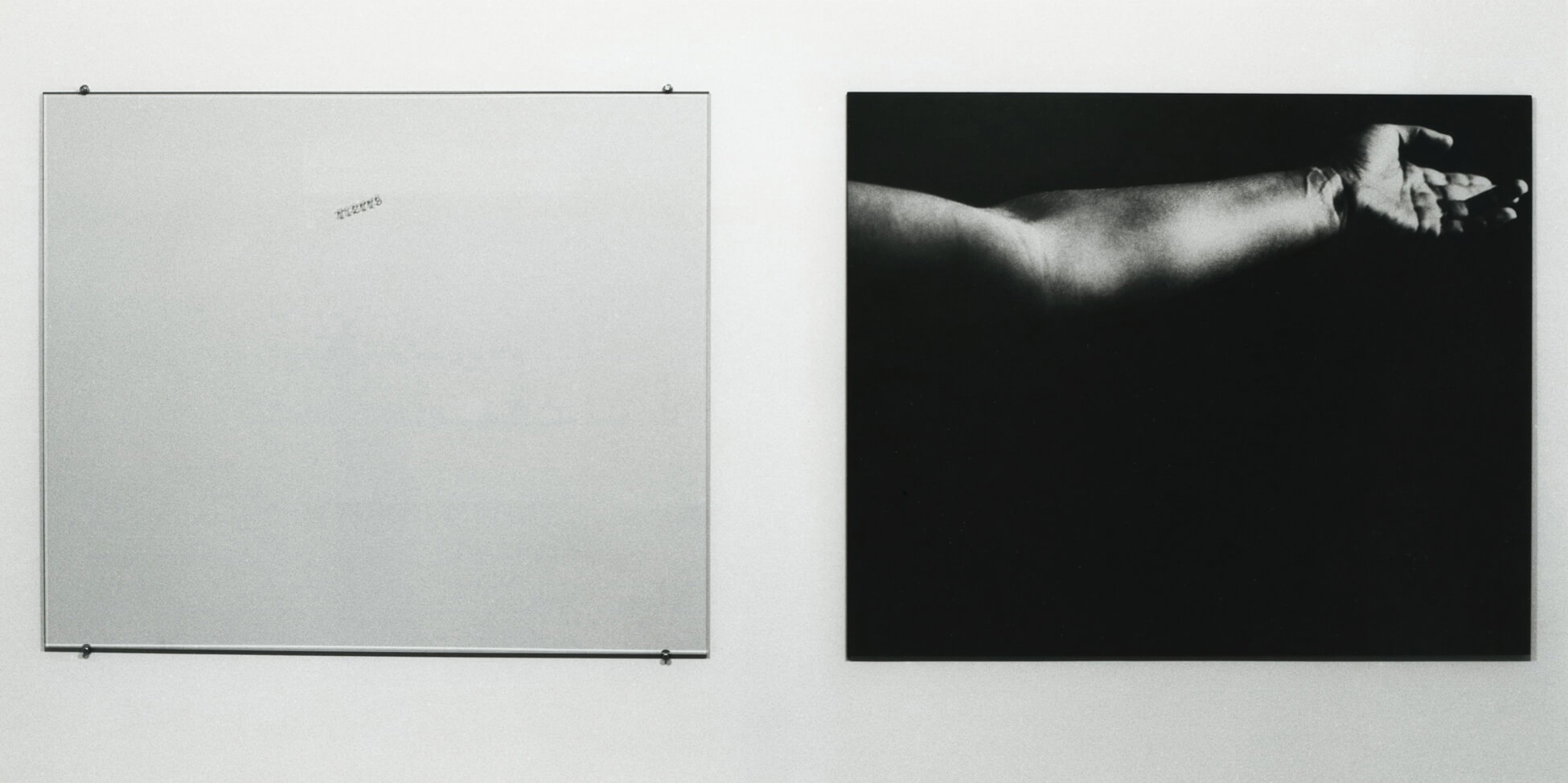

The elegiac black and white photographic diptych Of a Place, Solitary Of a Sound, Mute, 1989, by postwar-born Barbara Steinman (b.1950) captures her ongoing reflections on the enduring meaning of the Holocaust, which she did not directly experience. It also makes clear the legacy of the Holocaust not only for those who witnessed it but also for those who have come after. Steinman’s work consists of a piece of glass on the left into which a six-figure number has been etched. The number is legible only when the viewer stands in front of the image on the right, where a bare left arm extends outward like the arm of the crucified Christ. The image evokes the tattooing of prisoners in Auschwitz.

Today, Canada’s newest national memorial is Ottawa’s Landscape of Loss, Memory and Survival: The National Holocaust Monument, 2017. The structure, which depicts a Star of David with six triangular volumes at each of its points, was created by Polish American architect of Jewish museums Daniel Libeskind (b.1946) and landscape architect Claude Cormier (b.1960). It features the work of Edward Burtynsky (b.1955), who visited sites related to the Holocaust all over Europe and took over 250 photographs, six of which are integrated into the monument’s design.

The Cold War

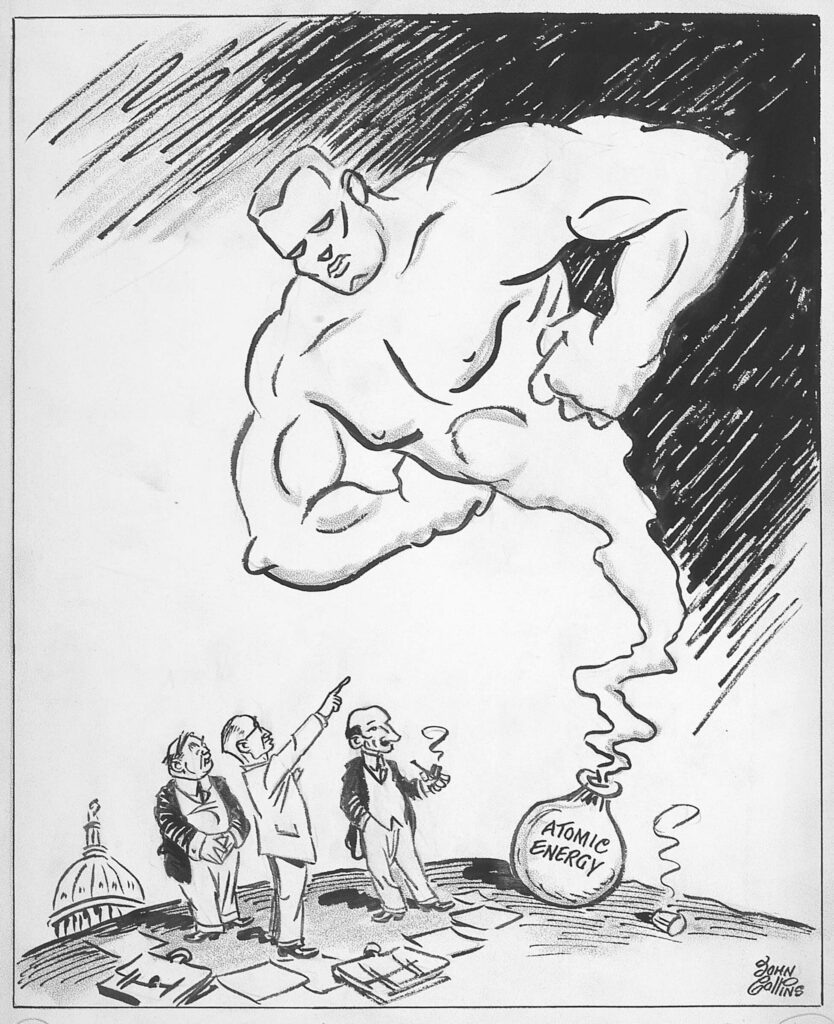

Compared to the First and Second World Wars, which were, respectively, four and six years long, the Cold War, 1945–89, lasted more than four decades and encompassed a number of conflicts. During the Cold War, geopolitical tensions ran high between the capitalist United States and its Western allies and the communist Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc. The threat of nuclear annihilation was a constant presence as both sides expanded their atomic capabilities. Montreal Gazette cartoonist John Collins (1917–2007) titled one of his editorial cartoons How Do We Put the Genie Back in the Bottle?—the drawing shows a large genie emerging from a small bottle labelled “nuclear energy.” In his sculpture of the Northwest Territories, Emanuel Hahn depicted a figure carrying uranium radiating energy, alluding to Canada’s rich nuclear resources. Inconclusive wars were fought in Korea, 1950–53, and, more significantly, in Vietnam, 1955–75. Canada fought in Korea but not in Vietnam. The Cold War ended with the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which permitted the reunification of East and West Germany.

In its subjects and modes of representation, the art world inevitably reflected the violence and challenges of major geopolitical change and conflict, though Canada did so less dramatically than its neighbour to the south. In part, Canadians of the time viewed themselves as global peacemakers rather than a military force, even though they retained an active military. Canada’s prime minister Lester B. Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for effectively supporting the creation of a United Nations military force to bring about peace in Egypt during the 1956 Suez Crisis. As a result, the war art of the period tends to document military activity as a peacekeeping occupation or protest conflict in support of peace. Furthermore, for the first time, official art is not pre-eminent in terms of artistic reputation.

From the Canadian Forces’ point of view, photography, as documentation, was the most important medium. One intriguing example of a photograph from the Korean War—the conflict between North Korea (supported by China) and South Korea (supported by Western allies including Canada)—shows future Quebec premier René Lévesque working as a journalist for Radio Canada International and fording a small stream, arms raised to hold his tape recorder on his head. This photograph, among many, shows how much conflict is woven into the Canadian fabric and how it is interlaced in the lives of its leading political figures, its history, and its visual culture. Dozens of images recorded the actions of Canadian troops in Korea, doing everything from marching across the land to fighting with a flamethrower.

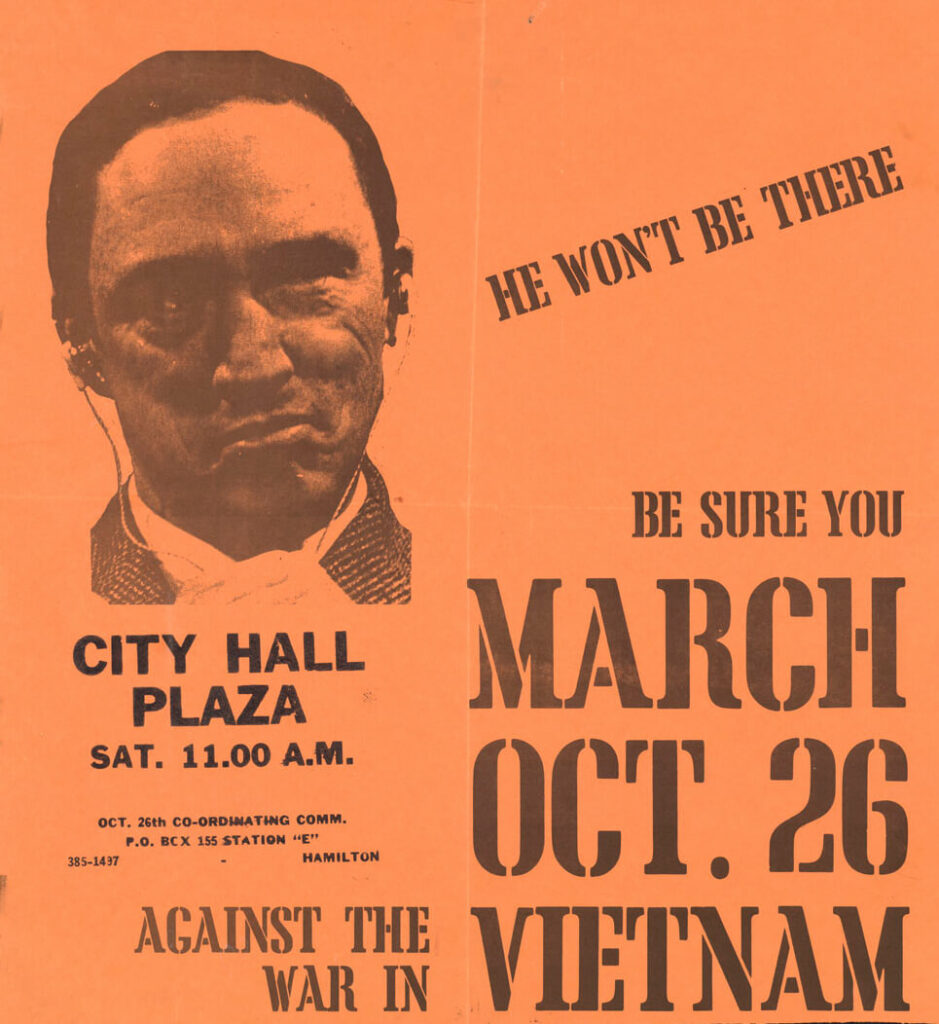

A collection of official war art remained an aspirational goal. In January 1954, during the early stages of the Cold War, in the absence of an official art program, the Royal Canadian Air Force commissioned former Second World War veteran, Spitfire pilot, and official war artist Robert Hyndman (1915–2009) to paint military activity at Canadian air bases in France and West Germany. Theoretically, Married Quarters under Construction at 4 Wing, Baden, 1954, shows the accommodation for the year-old air force base in Baden-Soellingen, West Germany, one of several Allied bases established to ensure peace after the war. In fact, it is a traditional landscape that includes a river or road, fertile green fields, a ribbon of green forest, and distant grey-blue mountain peaks. The absence of a military presence might negate its value as war art in some eyes, but the presence of construction cranes reminds us that this country is Allied-occupied Germany and that, nine years after the end of the Second World War, uneasiness remains.