Kazuo Nakamura defied convention as an artist and yet found critical success. He worked across figurative and abstract traditions, straddled art and science, experimented continuously in a wide variety of styles and techniques, and was the only member of Painters Eleven—one of the most important groups in Canadian art history—who was Asian Canadian. Throughout his career, he followed his own interests and drew little attention to himself or his work, but his art struck a chord. His experience of internment led him to explore themes of identity and belonging, and universal truths such as the laws of nature found in mathematics and science. With patience and single-mindedness, he produced a rich body of work that has laid the groundwork for a new generation of artists and a more inclusive art history.

Identity and Belonging

Like many Japanese Canadians who were interned during the Second World War, Kazuo Nakamura appears to have struggled with racism, his identity as both Japanese and Canadian, and his sense of his place within the Japanese Canadian community and broader Canadian society. This feeling of confusion was compounded by the bombing of Hiroshima, where his parents were born and many relatives still lived. These experiences may have generated a slight distrust of other people: there is a near-total absence of human figures in the paintings he made after leaving the Tashme internment camp.

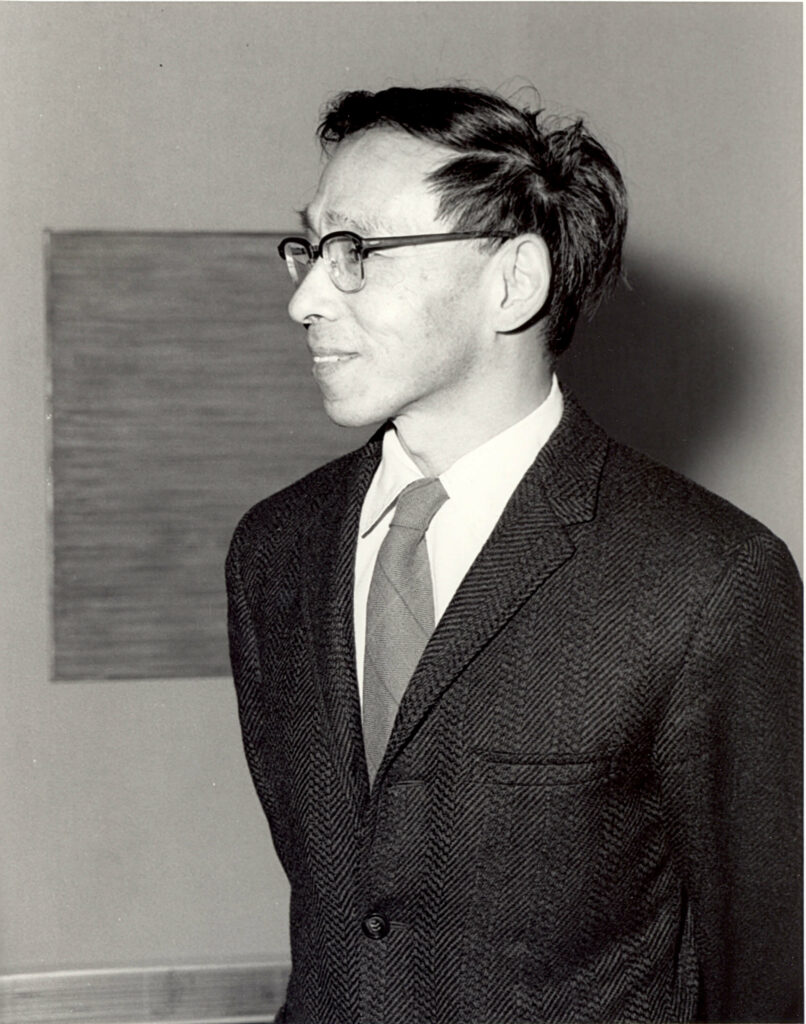

Nakamura did not necessarily shy away from social events, but he was perceived as polite yet reserved, something of an introvert. Art writer Iris Nowell described Nakamura in the company of his colleagues in Painters Eleven: “The non-drinking, non-smoking, non-carousing, apple-loving Kazuo regularly attended art openings and parties in support of his colleagues. An opening, after all, was a celebration. Nakamura could always be seen at the host gallery walking up and down, seriously studying the work of his friends and colleagues, unlike many others whose principal interest at openings was the location of the bar.” It is difficult to know how much of this reserve was Nakamura’s innate temperament and how much might have been shaped by social and cultural experiences. Nakamura’s colleagues in Painters Eleven—all of whom were white and of European descent—would not have understood what it was like to be singled out for the colour of their skin, and in the 1950s Nakamura would not have encountered many other artists who shared his experience of internment and the unspoken shame it brought on many families.

Being something of an outsider put him in the ideal position as an artist who could observe and try to understand and reveal the larger problems of humanity’s place in the universe. Yet he longed to belong, as evidenced by his participation in Painters Eleven and his loyalty to its members even after the group disbanded, as well as his work for the Japanese community in Toronto, specifically the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

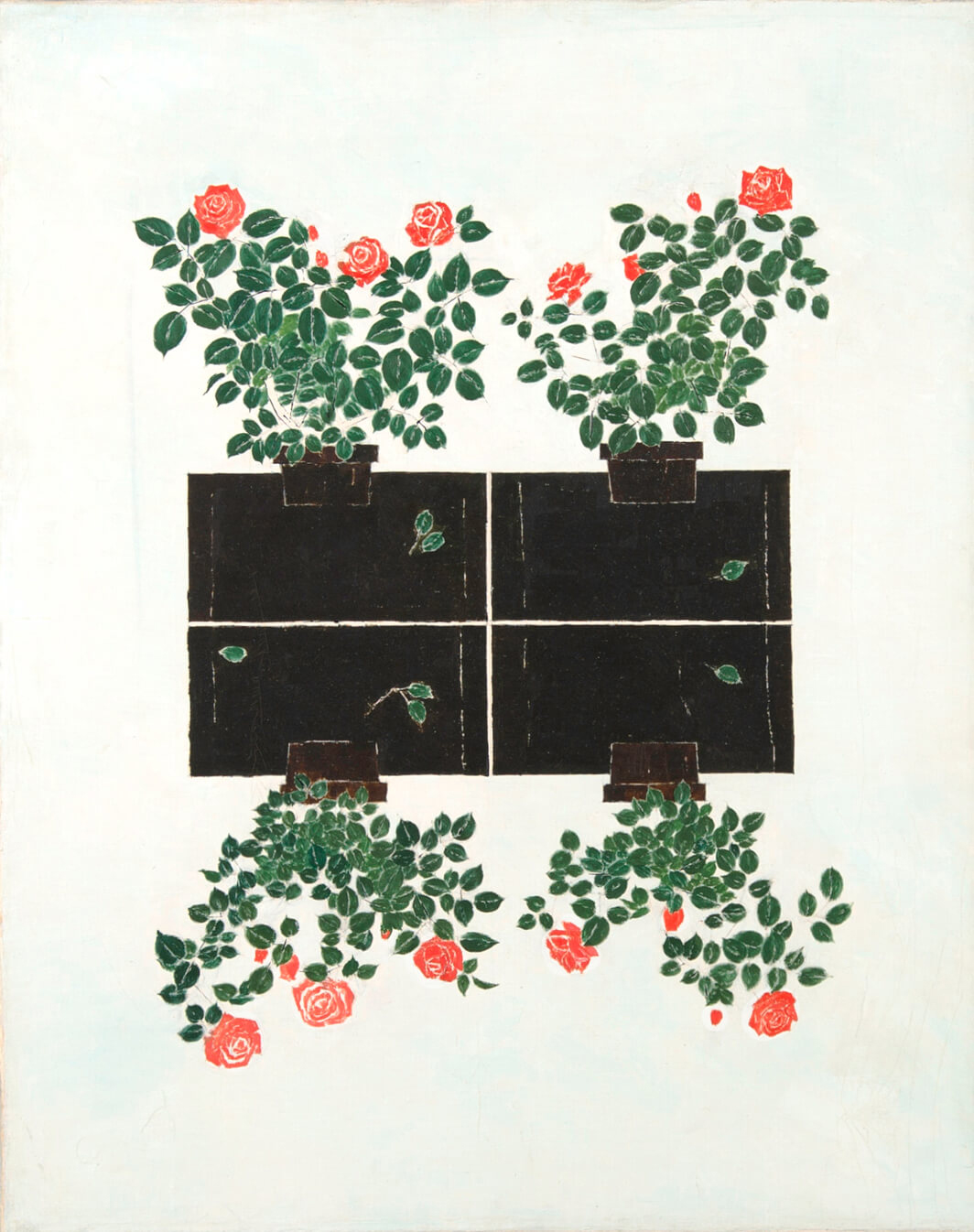

Paintings like those from the Suspension series or Reflection works appear to touch on issues of identity and belonging. The fruit and plants in Suspension 5, 1968—separate from each other and bounded from the background by heavy lines—suggest isolation and loneliness, despite their being the products of the elemental forces that shape our lives. Their rootlessness and seclusion evoke melancholy and sadness; these life forms seem to be in need of a place, a context to truly exist. That context simply will not appear, there is no sign of it, and the forms seem destined to be swallowed up by the black firmament.

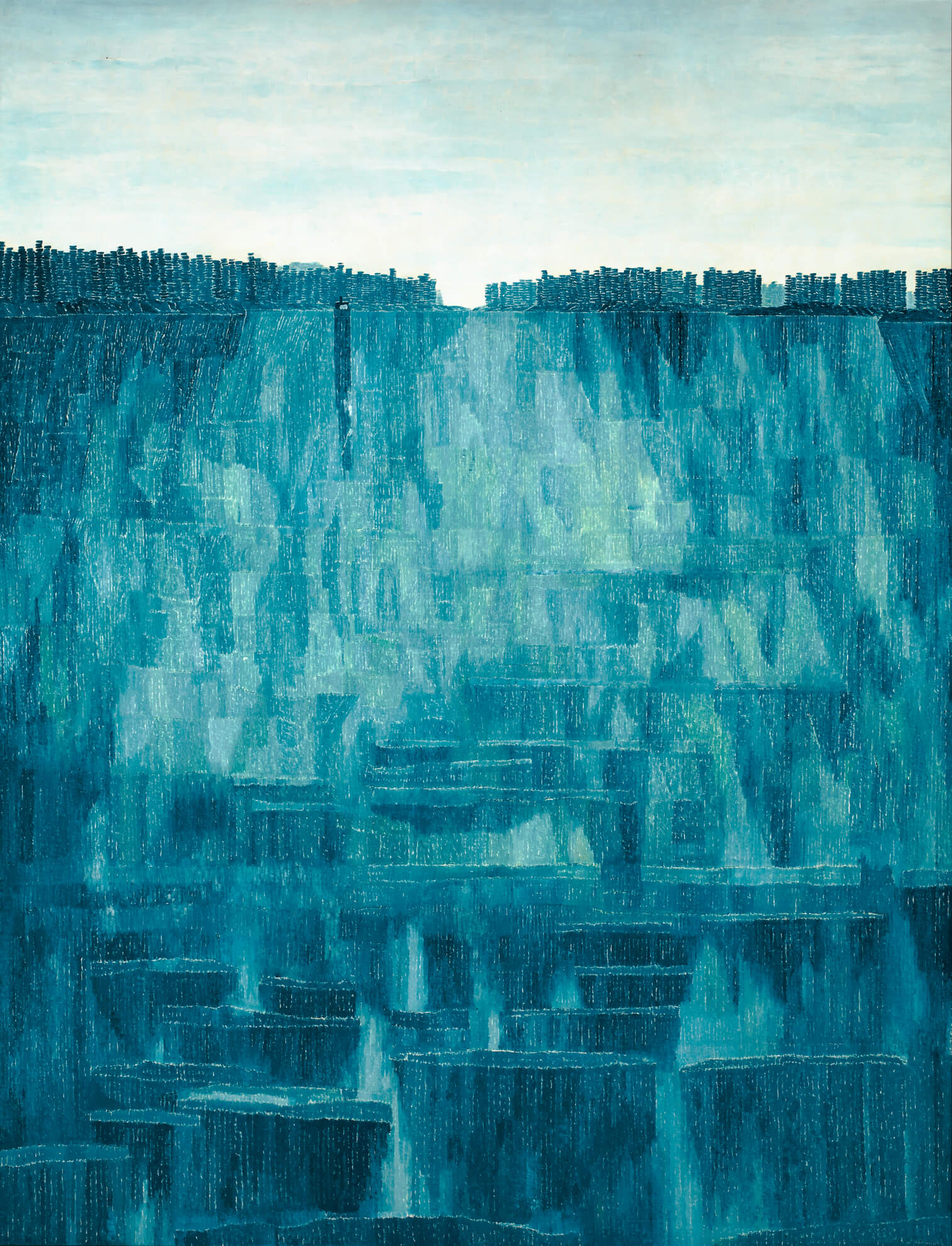

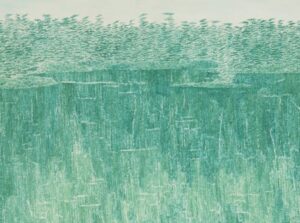

Similarly, in the Reflection works, in paintings like August, Morning Reflections, 1961, places are depicted but they feel lost and isolated—they are beautiful, but lacking, in being unoccupied or not providing any sign of being occupied. An exception is Lake, B.C., 1964, in which one spies at the horizon a very small boat casting a long shadow on the water. The boat appears to be departing, as if soon to leave the viewer, the artist, alone again, isolated in the most beautiful of places.

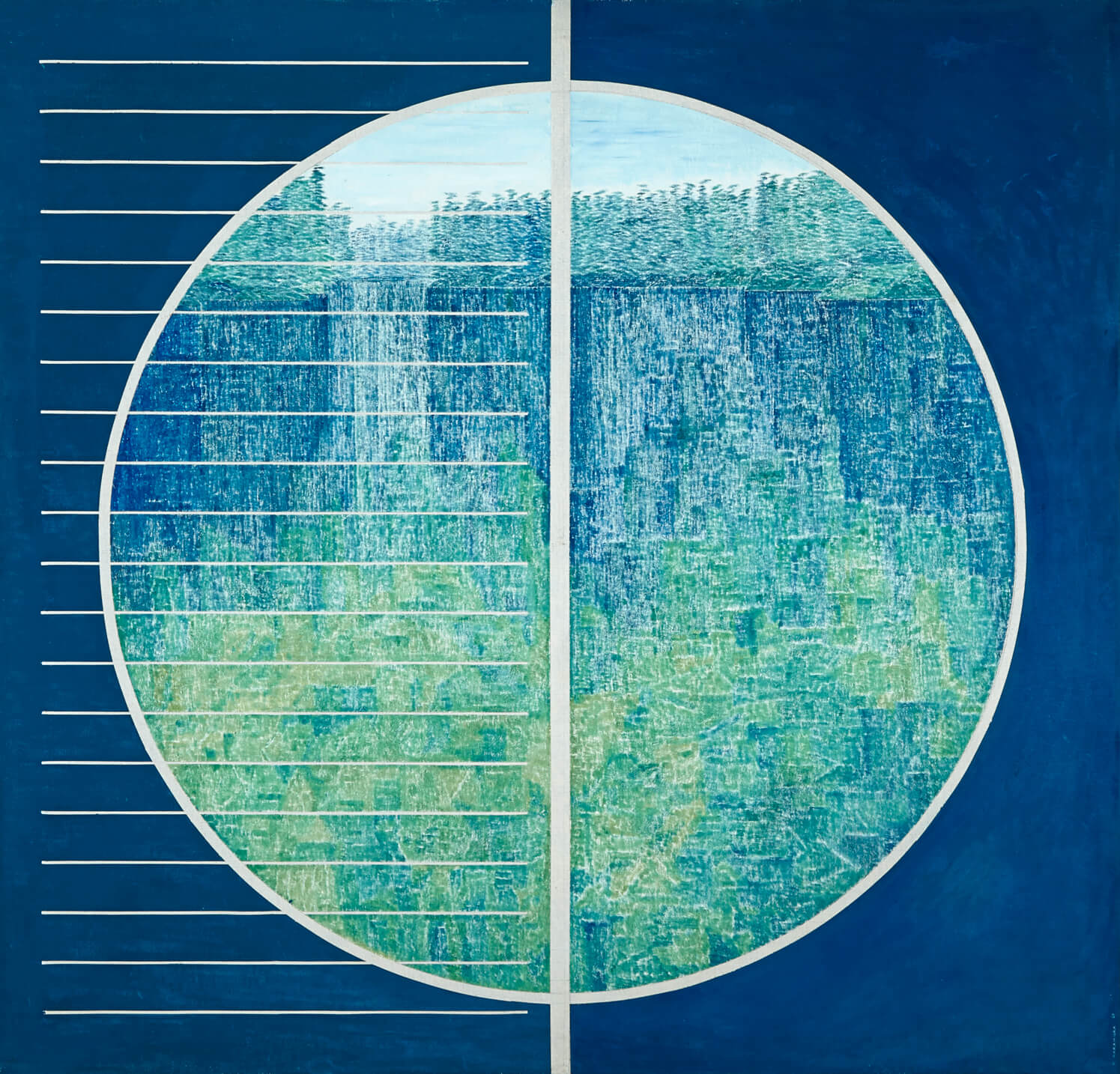

Suspended Landscape, 1969, effectively combines both of these types of works. We peer through a circular opening at a landscape, an outsider looking in on a scene. A vertical white line splits the canvas in half, and on the left side are horizontal lines stacked like an open blind. We seem to be invited into the lush lake setting at the same time that we are held back from entering it, a metaphor for the feeling of wanting to belong but not being able to, as Nakamura may have experienced it. At the same time, he may be underscoring humanity’s relatively small stature and isolation when measured against the immensity of the universe.

Modernism’s conception of avant-garde artists as visionaries who struggled to belong because they were ahead of their time seems to have resonated with Nakamura. Though part of society, the avant-garde artist possesses a deeper knowledge, an insight into how society will progress. In a taped interview from 1967, Nakamura revealed:

The contribution of the artist is to extend visual knowledge as a way of understanding our universe. I, as an artist, am never wholly isolated from anyone else, from the labourer or the scientist. We are all, each in his own way, making a new society, or a part of that society. On the other hand, since some perception and foresight beyond the norm is a necessary attribute of the functioning artist, I must admit to a certain sense of unavoidable “apartness.”

In any period of art there is always an accepted mainstream and an outer fringe, not yet accepted, that tries new ideas. And then, in time, that outer fringe becomes the influence of another mainstream. Although I am as much concerned with the future, with what is going to happen, as with the present, when I am actually painting or making sculpture, I just try to work out my own ideas, with no conscious thought of a breakthrough. If I am truly inventive, I will inevitably work on that outer fringe, where every real artist yearns to be … although most of us today are not quite sure just how we should place ourselves!

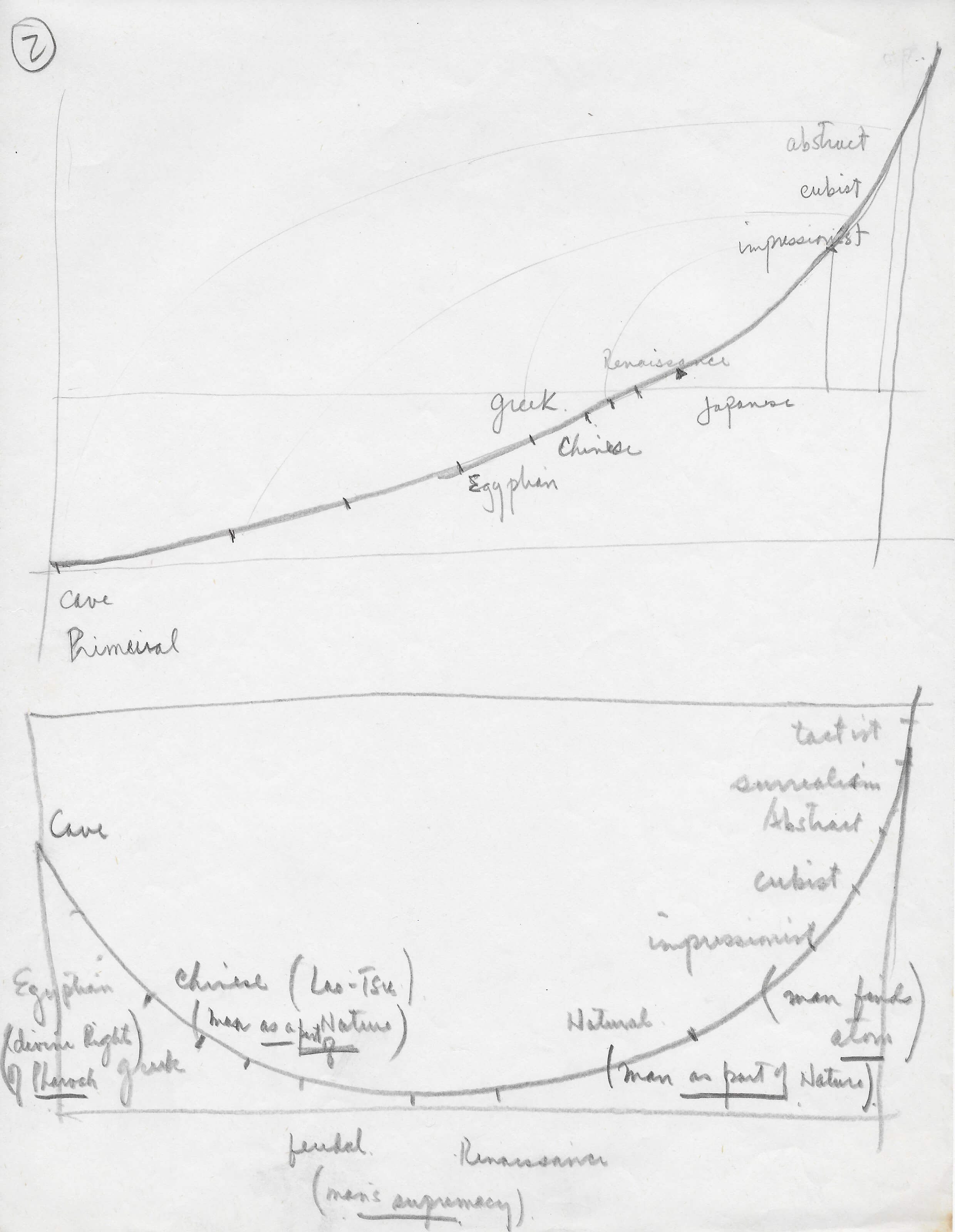

It is fascinating to see how the events of Nakamura’s early life and the ideas he explored in his art informed the work he produced and reflected his self-image as an artist throughout his career. As early as 1941 with First Frost, one senses the excitement with which he registers his love for the city; however, once he was barred from returning to Vancouver after the Second World War, he struggled to find his place. Here he began his quest to find the forces that make our world, in the hope of understanding our place in it. It is unclear whether he ever found an answer to either question. Nakamura’s Charts of the Evolution of Art, c.1980s, hints at reconciliation: he records the moment when Japanese art is integrated with Western art. And yet, his statement in a 1972 interview that Japanese Canadians would lose their Japanese identity through intermarriage suggests that he saw belonging—as both Japanese and Canadian—as impossible.

Revisiting Painters Eleven

Painters Eleven is central to any account of Kazuo Nakamura’s career: he was a founding member of the Toronto-based group of abstract painters and participated in many of its exhibitions. Yet he was surprisingly ambivalent about the group’s value to his career and those of his colleagues. In a 1979 interview with Joan Murray, Nakamura said, “For exhibition purposes it was helpful. Of course as a painter possibly we matured more after we left or Painters Eleven split, especially Jack Bush and Bill Ronald on their own became much better painters.” This was a view shared by Harold Town (1924–1990), who noted: “History perverts the progress of Painters Eleven, attempting to make us into a movement with a philosophy. We were simply a mechanism for exhibiting.” Ray Mead (1921–1998) felt that participation in Painters Eleven had strengthened all the members.

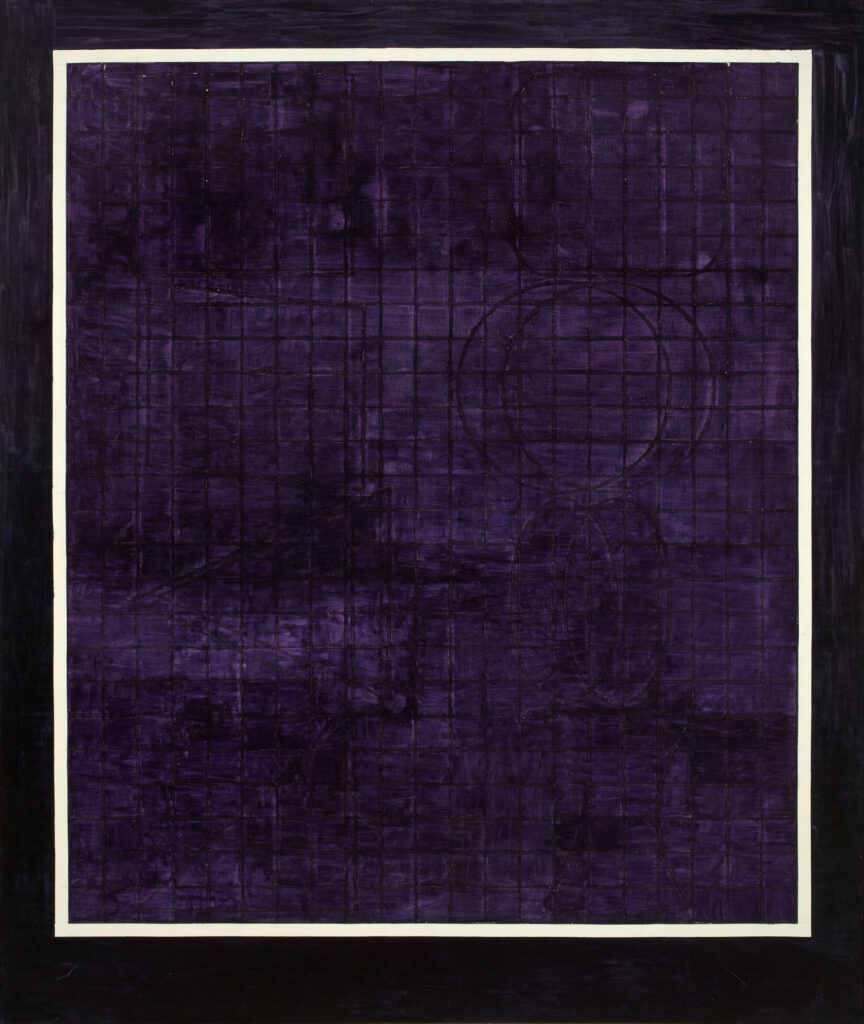

Harold Town, Tumult for a King, 1954, oil on Masonite, 140.7 x 95.8 cm, The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa.

Nakamura was not entirely wrong in what he had to say to Murray about Painters Eleven. The group was created mainly to better its members’ chances in finding exhibiting venues, especially given that their art looked radically new to Toronto audiences. They offered full-blown abstraction, largely gestural, like Mead’s Blue Horizon, c.1957, for instance, which followed from the work of the American Abstract Expressionists and the Automatistes in Montreal.

Nakamura must have seen the value of allying himself with other more established artists. By this time, for example, Jock Macdonald (1897–1960), his former art teacher (and soon-to-be colleague in Painters Eleven), had already opened many doors for Nakamura. The result was that between his last year at Central Technical School in 1951 and 1954, when Painters Eleven first exhibited under that name at Toronto’s Roberts Gallery, Nakamura’s exhibiting record was exceptional, to say the least.

Painters Eleven may have had no driving ideology, no modus operandi that the members had to adhere to, yet the group still had a vision. In a brochure for the group’s 1955 show, one finds the following statement: “There is no manifesto here for the times. There is no jury but time. By now there is little harmony in the noticeable disagreement. But there is a profound regard for the consequences of our complete freedom.” In other words, there is no grand scheme, no concordance between the works presented, no unifying script the artists are adhering to. The works are simply an open and free expression aimed at protecting that freedom. Tom Hodgson (1924–2006) asserted in a 1990 interview with Joan Murray, “It was their business what they did and no one ever said anything about anybody else’s work.” And Nakamura likely joined the other ten artists precisely because it left him free to continue along the artistic paths he was already taking.

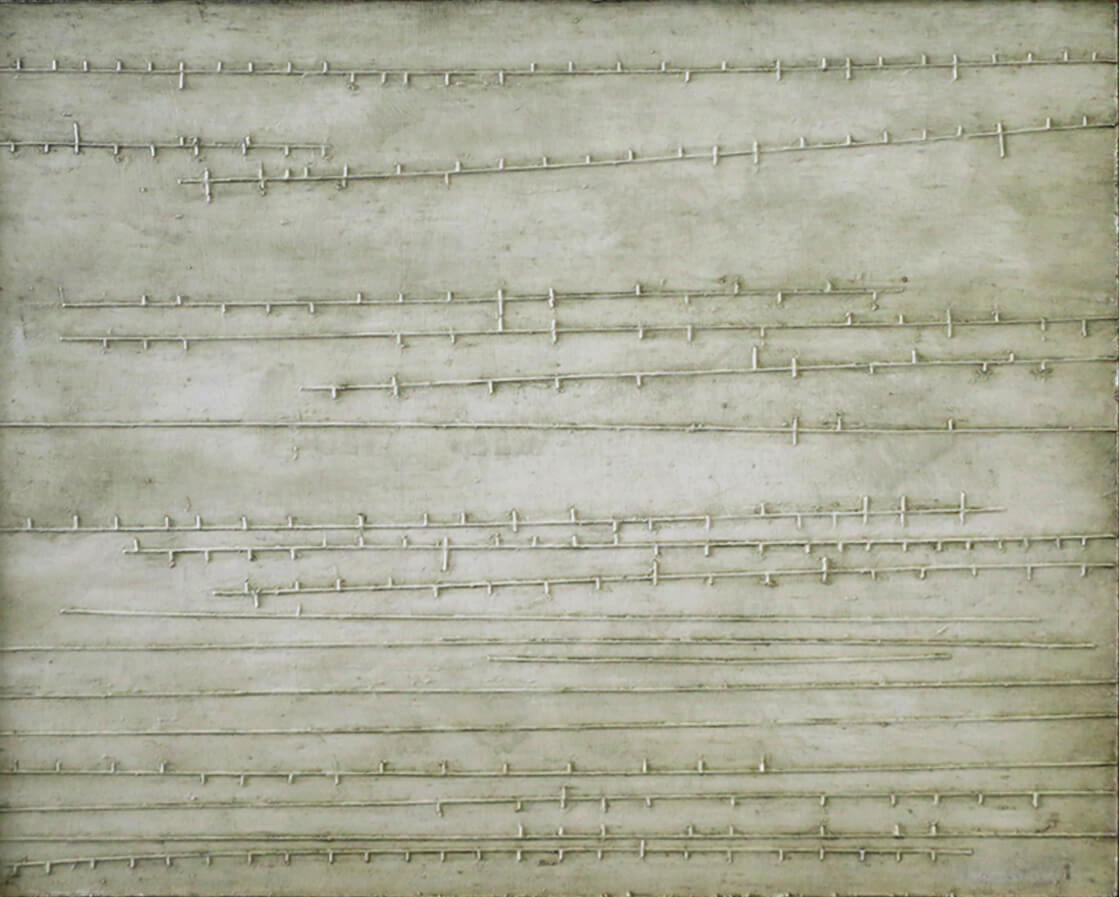

Painters Eleven members might not have influenced each other’s work overtly, but it is probable that, even if Nakamura did not recognize its impact, seeing his colleagues’ art gave him the courage to experiment. It may even have accelerated his progress in the path he was on. The 1950s was one of the most creative periods of Nakamura’s career. Not only did his landscape paintings grow more abstract, but he also created the Block paintings, like Prairie Towers, 1956; the Inner Structure works; and the radical String paintings. Visually, Nakamura’s paintings did remain quite distinct from the others. But to expect that the members’ work changed or improved as a result of Painters Eleven might be seen as something of a fallacy. That was not the point.

Not to be overlooked, though, were the camaraderie and respect among the artists of Painters Eleven. Nakamura forged friendships with the other members at a critical moment in his life. He had moved many times in the previous decade and been barred from returning to communities in his hometown and home province: he was isolated literally and figuratively. To find a coterie of individuals who so welcomed and accepted people for who they were must have been a godsend for Nakamura. In turn, he remained loyal to his colleagues, attending many of their openings throughout the rest of his life, and clipping and saving exhibition reviews of their work.

Art and Science

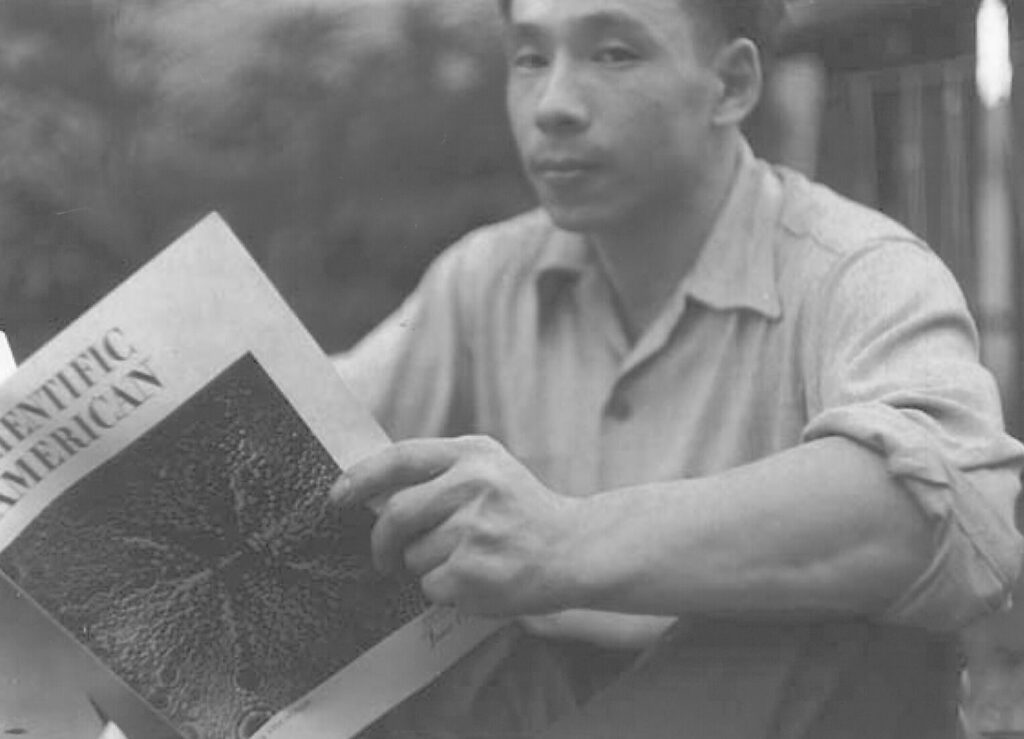

Kazuo Nakamura’s Number Structure works from 1975 on epitomize his interest in science. So too does a well-known photograph from 1957 in which he is holding open a copy of Scientific American, one of his favourite publications. It is difficult to establish exactly when his curiosity about science first emerged, though he said that having been interned, he felt he had lost the time required for the study he would have needed to become a professional scientist, and decided to go into art instead. This suggests that he may have been considering a career in science as early as his teenage years.

Even in his earliest statements about his art, Nakamura spoke of seeking out and striving to reveal an underlying structure in the world. For example, journalist Robert Fulford reported in 1956:

Nakamura picked up a microscopic photograph of the nerve plexus of the human intestine and placed it beside a print of a religious painting by the 14th century Sienese painter Duccio. Then he pointed out the relationship between the two. “They have the same basic pattern,” he said. “Rhythms are the same. In fact, I think there’s a sort of fundamental universal pattern in all art and nature. Painters are learning a lot from the physical sciences now. In a sense, scientists and artists are doing the same thing. This world of pattern is the world we are discovering together.”

We know little specific detail about Nakamura’s studies, but Jock Macdonald, who taught him in Vancouver and was later a member of Painters Eleven, could have been an influence. Macdonald’s interest in science and mathematics dated back to at least the 1930s, as seen in works like Departing Day, 1939, although it was mediated through the mystic philosophies of theosophy and anthroposophy. Nakamura, however, was adamant on the point that Macdonald had little impact when it came to his interest in science, and that it was he who had suggested that Macdonald read Scientific American. Nakamura revealed that he also read books by artists such as László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), who embraced science and modern technology with far less of a mystical inclination than Macdonald.

Nakamura’s interest in science emerged in earnest in 1957. The fact that he encouraged Macdonald to read Scientific American when they were members of Painters Eleven, rather than when they were at Vancouver Technical Secondary School together, suggests that Nakamura discovered the magazine only around this time. From that moment on, Nakamura’s statements regarding science increased exponentially and he began to take cues about his art from science. The String paintings, such as Untitled (Strings Removed), c.1957, were the first such works, inspired by the traces of subatomic particles. It is no coincidence that when he was pictured with Scientific American, Nakamura held the June 1957 issue, whose theme was Atoms Visualized.

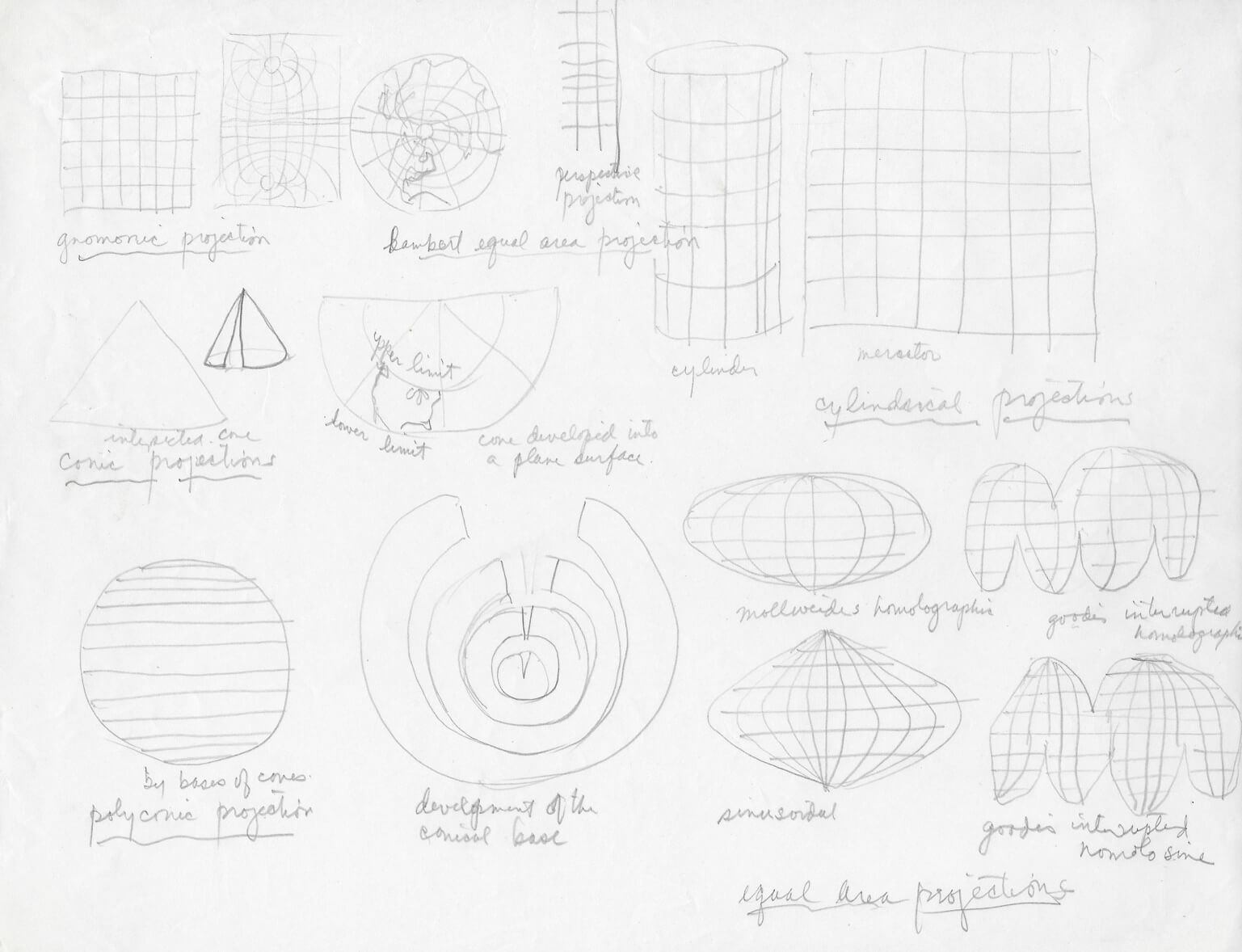

Nakamura’s attraction to science, beyond his youthful desire to be a scientist, may also have been related to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although he rarely discussed these events, they appear to have prompted an interest in the physics behind the atom bomb. Relativity theory and quantum physics are not easy fields for a layperson to grasp, but Scientific American offered an accessible entry point. These fields became hugely popular in the 1950s and 1960s, even covered in daily newspapers, with the beginning of the space race. Nakamura himself preserved many of these newspaper stories, from the discovery of a new type of neutrino and anti-neutrino to the moon landing and radio telescopes. He took copious notes on evolutionary theory, astronomy, and quantum theory, and produced many drawings using surprisingly sophisticated geometry, such as Geometric Projections, n.d.

By the 1960s Nakamura was comparing the development of science with the development of the arts. He even noted the parallels between the struggle for acceptance that new ideas in science had experienced and abstract art’s struggle to find an audience:

The science of art is at its most interesting stage. Through history, in man’s search of knowledge, new thoughts such as Copernicus’ theory of solar system, Darwin’s theory of evolution, etc., have caused controversy. Art and its theory at present is a very controversial dilemma due to the lack of adequate basic theory.

Significantly, Nakamura refers to “the science of art” in this passage. He did see his approach to art as simply a different form of scientific inquiry, since he held that art and science were part of the same historical zeitgeist. He added:

In the history of art, all civilization and its developing period must be relative to the universal scientific and philosophic concept of its time (or the scientific and philosophic concept may be relative to art). Every developing phase and facet of science must produce some form of art. atomic/ molecular/ cellular/ inorganic and organic/ mental and mechanical/ planetary/ solar system/ galaxial/ the universe.

More importantly, for Nakamura art was the linchpin to understanding what science has to say. In a 1972 interview he explained:

Through understanding culture, man will understand himself and his universe. The physical and natural sciences will get quite close to this understanding but won’t know the whole evolution of the universe. Through culture—which will be part of science—man will understand man and the universe.

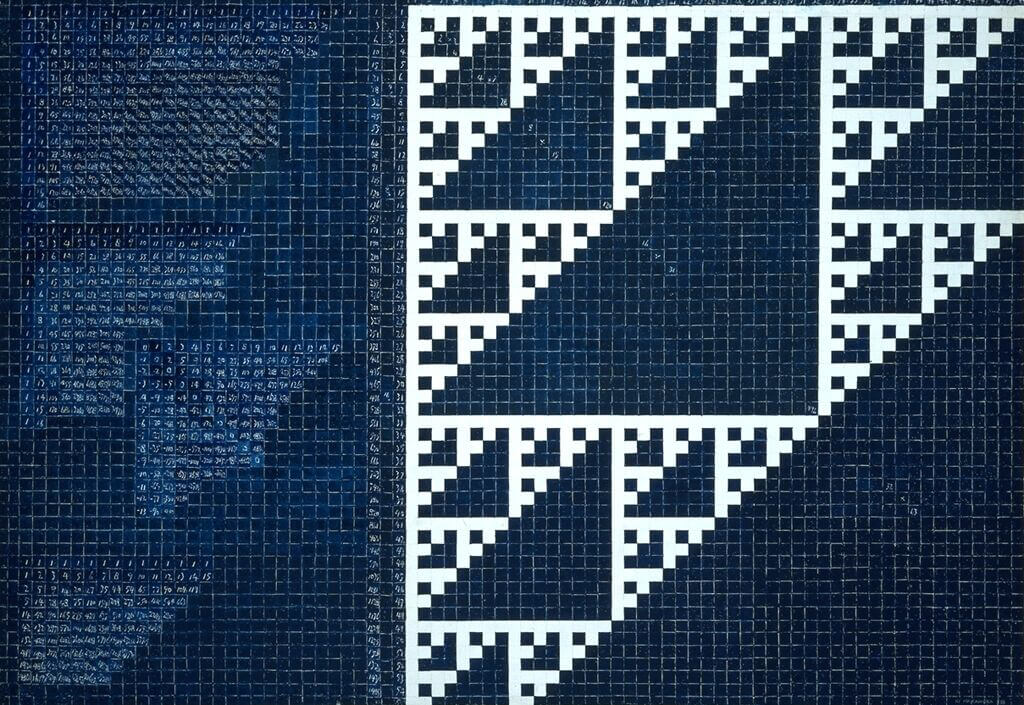

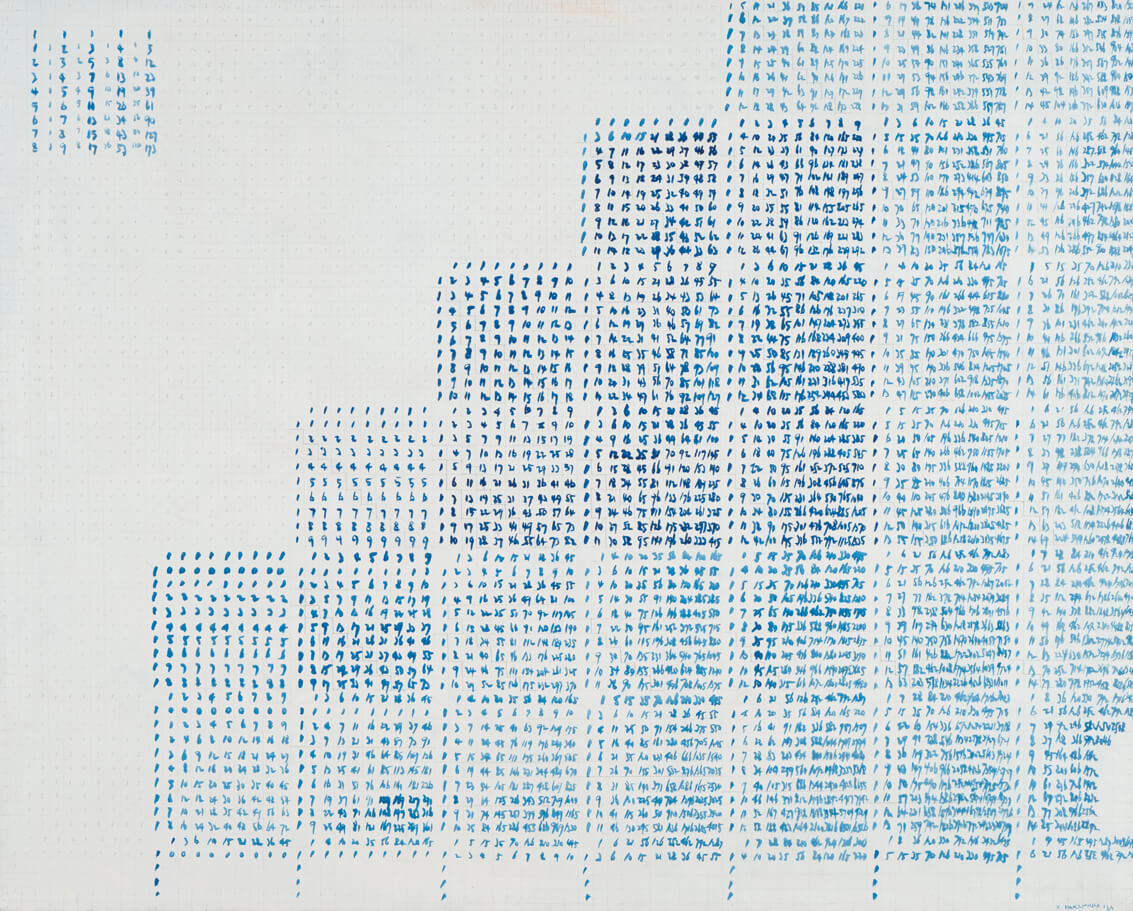

In other words, art provides, in a sense, the rationale to understand our place in the universe: without it, science lacks purpose and meaning. It is with works like Number Structure and Fractals, 1983, where the artist visualizes the world of numbers whose structure shapes our visible world, that Nakamura finally achieved what he believed was the perfect marriage between art and science.

Alternating Currents: Representation and Abstraction

Although some artists are unequivocal about working in a representational or abstract style, and feel that adopting one excludes the other, Kazuo Nakamura had no qualms about oscillating between the two throughout most of his career. For him, both styles were simply different ways of expressing the same thing, namely the underlying structure of the universe and its visible manifestations. This expression could make use of the language of figurative art, or geometry, or mathematics. It is not clear if Nakamura felt that one style was necessarily superior to another; they were likely just different lenses offering up their own unique perspective on the world.

Critics were quick to note this unusual characteristic of Nakamura’s work. Robert Fulford was one of the earliest, commenting in 1956:

He seems … to alternate between construction of tensely two-dimensional lines and imaginative spatial essays that show an unorthodox vision of perspective. It is as if he were a Bach one day and a Beethoven the next. When this was written Nakamura was painting powerful three-dimensional cubes that looked like hollowed out cement buildings. They vaguely suggested a combination of Salvador Dali and Piet Mondrian.

Harry Malcolmson raised the issue of Nakamura’s alternating styles again almost a decade later:

Most artists adopt a painting style, work it through, then go on to some new style. Not Nakamura. At all times he maintains a minimum of three styles, each of which he develops simultaneously. Every time he opens a show, as he has this past week at the Morris Gallery, each of his styles will be pushed forward along parallel paths…. It doesn’t tell me anything to be told by a collector he likes Nakamura. It’s necessary to go on and find which Nakamura it is they mean.

In the Morris Gallery show of 1965, for example, Malcolmson might have encountered works as different as Lake, B.C., 1964; Untitled, 1964; and Structure, Two Horizons, 1964.

Another writer, Paul Gladu, opined in 1967 that fundamental similarities exist between the diverse styles in Nakamura’s oeuvre: “Their oscillation between realism and abstraction never fails to express the same sense of solitude and emptiness together with a certain gentleness and refinement usually associated, in our mind, with the philosophies of the East.” Although Gladu appeared to read a bit too much into the works, he nevertheless recognized that fundamentally the different styles are similar.

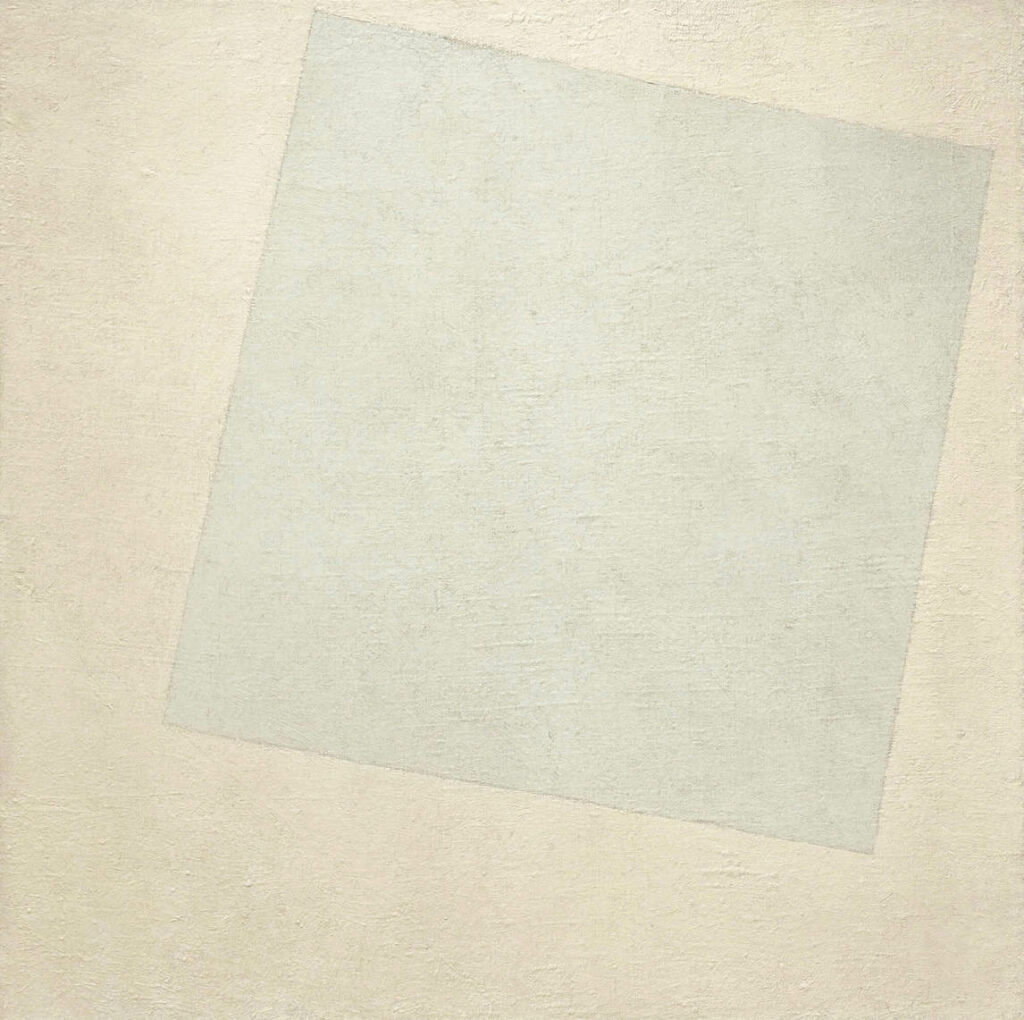

Abstraction in art dates to the beginning of the twentieth century and has two main forms. The first abstracts from nature. The artist observes the seen world and distills it into its essence, as illustrated famously by the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) in Composition VIII (The Cow) [4 Stages of Abstraction], c.1917. A subset of this first form of abstraction copies nature but at a more fundamental level that captures its underlying laws. Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) painted this way. The second form is pure expression. The artist manifests the unseen—music, spiritualism, emotions, for example—and renders its elements using non-descriptive forms such as line and colour. The work of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) is an example, as are most of Painters Eleven. Nakamura does not fit neatly into any of these groups, except maybe in arriving at a solution with his Number Structure paintings that was akin to what Malevich arrived at with his White on White paintings. Both created an ultimate abstract painting.

Yet the problem Nakamura tackled in all of his works was basically the same need to understand the world. He just chose to tackle it from different angles, using different tools and different stylistic approaches. In this respect he was much like Paul Klee (1879–1940), with whom he is often compared, though he denied any influence. Nakamura was nevertheless systematic in his experimentation, as the various styles appear to peel back distinct layers of our world, from the visible to the elemental, until he settled on the Number Structures. As Number Structure No. 9, 1984, illustrates, he revealed through numbers, and the sequences they can generate, the essence of the natural world and its underlying laws. Even then he never gave up figurative work entirely. Nakamura continued to paint the occasional landscape, which sold well and where he could focus on the surface rather than the more demanding underlying patterns and processes.

Influence and Legacy

Kazuo Nakamura has not had the exposure of some of his Painters Eleven peers like Jack Bush (1909–1977) or Harold Town. Despite how innovative he was, his works do not draw attention to themselves, being small in scale and equable in subject matter, and the uniqueness of his style and its variety somewhat inimitable. To Canadians generally, Nakamura’s name and work are not well known.

He has, however, drawn the attention of composers, animators, and architects. Polish-born Canadian composer Harry Freedman (1922–2005) wrote Images (1958), musical impressions inspired by Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970), Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), and Nakamura. In 2018, a jazz quartet helmed by Nakamura’s son-in-law, Jay Boehmer, performed The Kazuo Nakamura Project at the Christopher Cutts Gallery, Toronto. Most recently, Toronto musician Heraclitus Akimbo (Joe Strutt) wrote and recorded “Inner Structure (for Kazuo Nakamura)” on his album Catastrophic Forgetting (2020). As part of the Eleven in Motion: Abstract Expressions in Animation project inspired by Painters Eleven, artist and filmmaker Patrick Jenkins created Inner View, a short animation based on Nakamura’s work. And for his master’s thesis in 2008, architecture student Kevin James proposed an award-winning memorial for Japanese Canadians interned during the Second World War that was substantially informed by Nakamura’s abstract paintings.

A few painters, such as Alex Cameron (b.1947), admire Nakamura greatly even if he has not directly influenced their work. However, Nakamura’s success—like that of peers like Takao Tanabe (b.1926) and Roy Kiyooka (1926–2004)—has laid the groundwork for younger generations of Japanese Canadian artists, including Louise Noguchi (b.1958), Heather Yamada (b.1951), Warren Hoyano (b.1954), and their successors such as Emma Nishimura (b.1982) and Cindy Mochizuki (b.1976), whose achievements have been well chronicled over the years by artist and curator Bryce Kanbara (b.1947). As Louise Noguchi stated: “Kaz’s presence on the Canadian artscene made it feasible to imagine that other Nikkei artists could become recognized in both the Japanese Canadian community and in mainstream Canadian society. Kaz validated the idea of being an artist in the community. Perhaps it wasn’t such a crazy endeavour.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements