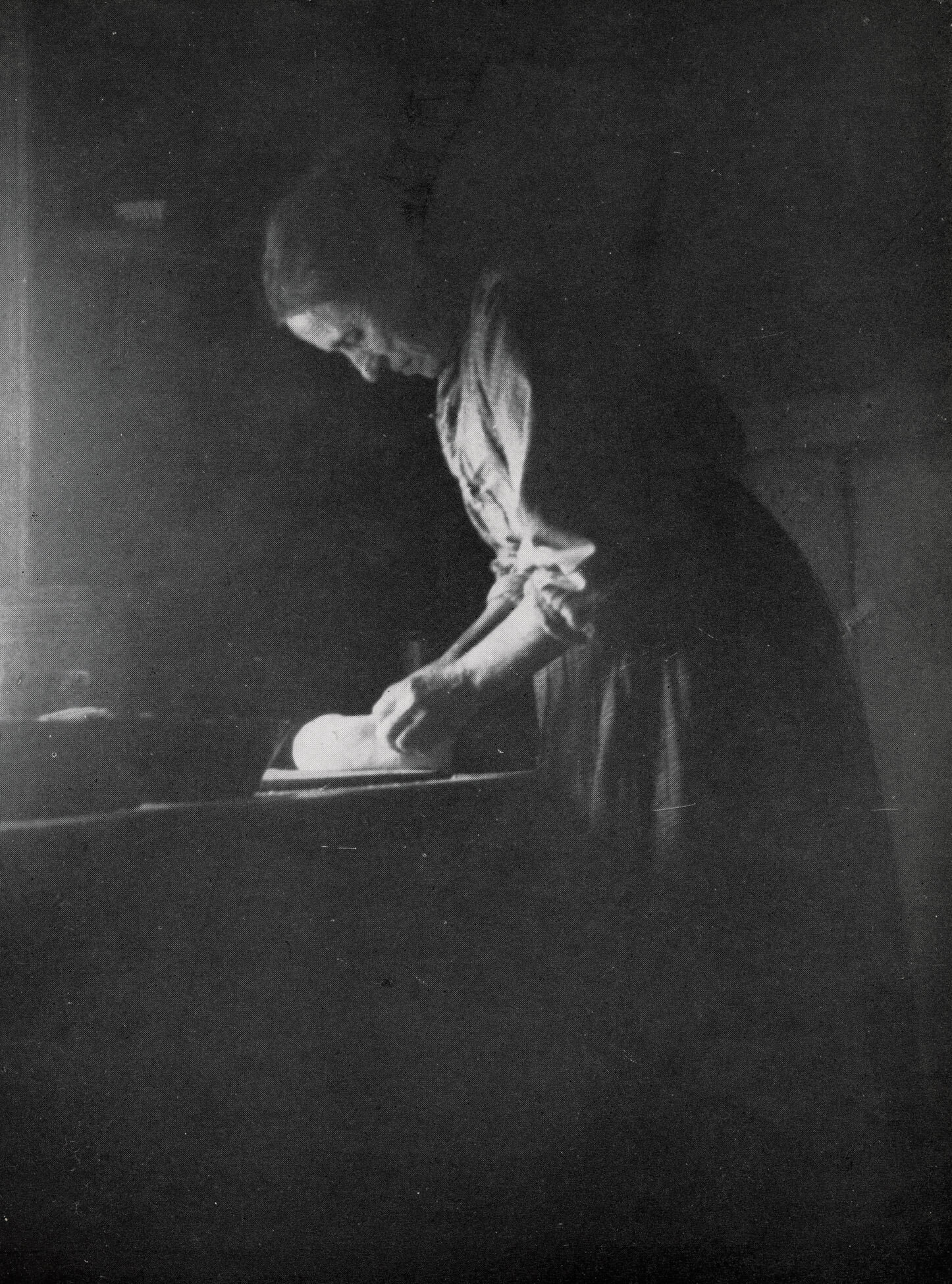

Edith S. Watson (1861, East Windsor Hill, Connecticut–1943, St. Petersburg, Florida)

Canada, “the Bread-Mother” of the World, 1922

From Victoria Hayward, Romantic Canada (1922)

In both title and its use of theatrical lighting, Canada, “the Bread-Mother” of the World, elevates the daily act of making bread. This photograph is among dozens of aestheticized images of rural labour created by Edith Watson (1861–1943). The photograph was published in Romantic Canada (1922), a book Watson developed in collaboration with journalist Victoria Hayward, her partner in work and life. Featuring seventy-seven halftone reproductions of Watson’s photographs, the book portrays Canada in a series of idyllic pre-industrial scenes that are unusual for highlighting women’s contributions to rural communities.

Watson grew up in Connecticut and likely learned photography from her uncle, a botanist, but found modest success as a watercolourist before embarking on her photography career. She began travelling to Newfoundland, at the time a British colony, in the early 1890s and later travelled to other parts of North America. Her first significant photographic commission was to contribute photographs for a travel narrative about Nova Scotia by author Margaret Morley. Each year for forty years, Watson returned to Canada for extended stays to photograph rural life across the country. She was particularly interested in the regions of Newfoundland and Labrador and the subject of women at work, a theme she also pursued when she lived with and photographed the Doukhobors in British Columbia over the course of three summers in the late 1910s.

Photographically, Watson’s strengths lay in composition and lighting, and she adapted stylistic elements of Pictorialism to create romanticized views of women’s domestic labour. Apparently, she never liked her Leica, but preferred simple box cameras that were easier to cart on her journeys even if the glass plates remained a burden to transport.

Determined to make a living from travel photography, Watson produced photographs that appealed to urban middle-class anglophone readers, and she sold her work to a wide range of magazines and publications, including Chatelaine, Maclean’s, the Canadian Magazine, National Geographic, and Ladies’ Home Journal, as well as governments and advertisers. She would also trade her prints for goods and services, including rail tickets and photography supplies. She was passionate about her work and insisted on being credited for her images when this was uncommon in mass media. She also declined invitations to publish her photographs in art journals and exhibitions as she would not be remunerated. However, Watson was also generous in sharing copies of her photographs with her subjects, and these images have made their way through families and into public collections.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements