When photography was introduced to Canada in 1839, it was first considered a novelty, but it quickly became a business and an art form. Before long, governments used photographs as documentation and evidence, while families assembled albums and told their histories with images. Photographers worked on city streets, in portrait studios, at tourist destinations, on expeditions, and at construction sites, and their photographs circulated in many forms and venues, including in albums, books, reports, newspapers, magazines, public lectures, and exhibitions. From 1839 to 1989, photography shaped societal norms, transforming how people engaged with others and how they understood the world.

1839–1850s: Photography Captures Public Interest

In the late 1830s, British North America was on the cusp of the industrial age. Montreal, in Lower Canada, was the largest city, while the newly incorporated city of Toronto was the economic and political heart of Upper Canada. Yet the colonies were a study in class contrasts. Oxen pulled carts down muddy streets that connected the ramshackle cottages of immigrants and labourers with the mansions of wealthy merchants. And people in the growing urban centres still looked to Britain, France, and the United States for the latest trends.

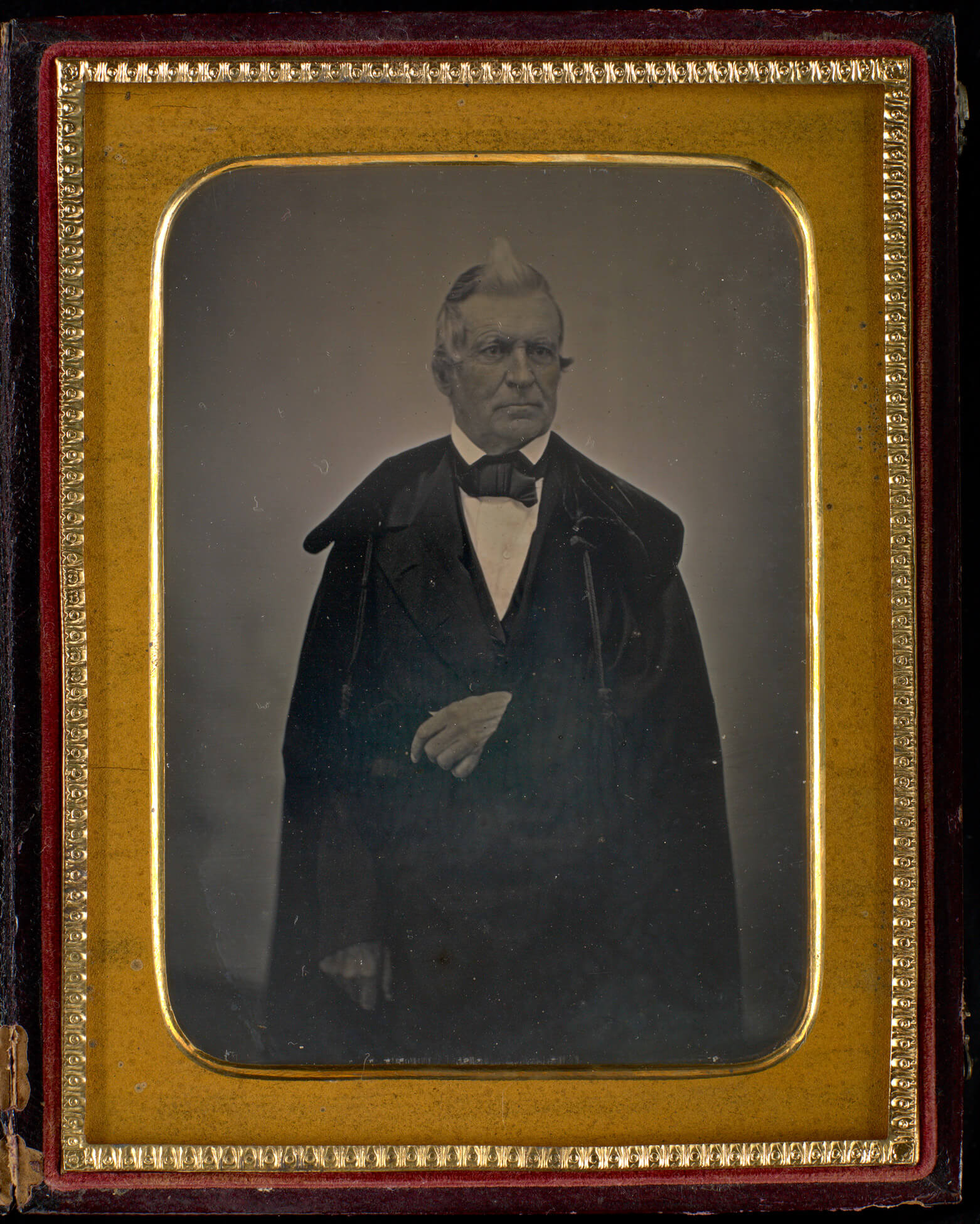

In 1839, news of a remarkable invention reached Torontonians via a letter in The Patriot newspaper. Readers were intrigued by Samuel Morse’s description of the elegant images created using the recently announced photographic process patented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851). Soon after, travellers began to practise the daguerreotype process in North America, producing crisp images on sheets of silver-plated copper. In the early years, there was much discussion in Europe and other regions about how the new invention would be used and whether it belonged in the realm of art or science. But in Canada and the United States, the commercial applications of the process were paramount. When itinerant daguerreotypists set up temporary studios in cities such as Montreal, Toronto, and Halifax in the early 1840s, advertising their services for “inimitable, and much admired likenesses,” patrons rushed to sit for portraits made not by a painter’s brush but by a photographer’s camera. The public was captivated by the beauty and exactness of daguerreotypes, and the upper and middle classes commissioned portraits as precious keepsakes.

Portraiture was by far the most popular application for photography at this time, and the first daguerreotypist to set up a more permanent studio in British North America was likely William Valentine (1798–1849), a former portrait painter, who offered photographic portraits in Halifax beginning in 1842. A few early practitioners became successful and received recognition for their work. These include Valentine’s former pupil and partner, Thomas Coffin Doane (1814–1896), who ran a gallery in Montreal from 1846 until 1865 where he made portraits of politicians and officials, and Eli J. Palmer (c.1821–c.1886), who was active in Toronto from 1849 until 1870. In the 1840s, photographers mainly worked in the growing urban centres of the newly formed Province of Canada, because the population was concentrated and the chemistry and equipment for making daguerreotypes was readily available from manufacturing centres in the northeastern United States.

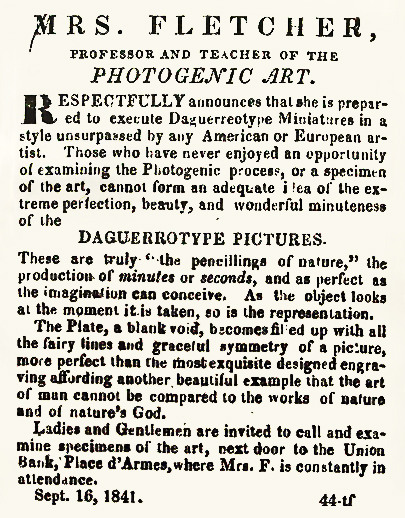

The early Canadian photography scene also included a woman known only as Mrs. Fletcher (active 1841), who was possibly the first woman in North America to become a professional photographer. Upon her arrival in Quebec City in 1841, Mrs. Fletcher advertised her services as a daguerreotypist and as a “Professor and Teacher of the Photogenic Art.” In addition to making daguerreotypes, she offered to instruct “ladies” in “a most respectable, tasteful, and pleasant employment, requiring but a few hours’ attention a day and producing an income from 15 to 30 dollars per week, either by settling in a city or travelling through any part of the civilized world.” Mrs. Fletcher’s enthusiastic attitude toward her specialty confirms what scholars have long argued: that women were involved in photography from the very beginning.

The market for portraiture was stimulated by a growing interest among the urban middle class in conveying social status through appearance, but enthusiasm for photography was not specific to any one class or cultural group. Contrary to the stereotype, many Indigenous people were as interested in photography as they were in other European technologies such as guns and in the metal objects that Indigenous people encountered through trade with settlers. One of the earliest portraits of an Indigenous person in a public collection in Canada depicts Maungwudaus (c.1807–after 1851), also known as George Henry, who was a Chief of the Mississauga First Nation and a government interpreter. This daguerreotype was made while Maungwudaus was touring Europe as a performer in the mid-1840s. Although public interest in portraiture continued, the next decade increased the range of subject matter and uses for photography.

Undeterred by the technical challenges of the daguerreotype process (including long exposure times), early photographers portrayed scenic views. In many instances, they were drawn to places of natural beauty, such as Montmorency Falls, Quebec. These were the same sites that fascinated other artists, and photographers sought to produce the kinds of picturesque views they encountered in drawing and painting. Newcastle industrialist and amateur photographer Hugh Lee Pattinson (1796–1858) made the first known daguerreotype of Niagara Falls on a trip to Canada. And selections of work by the Swiss-born Canadian Pierre-Gustave Joly de Lotbinière (1798–1865), who travelled to Greece and Egypt to photograph ancient monuments, were reproduced as aquatints in a book on Egypt by architect Hector Horeau.

As enthusiasm for new formats and uses of photography grew in its first two decades of existence, the stage was set for creating new businesses and different ways of imagining or presenting a nation.

1850s–1880s: The Business of Photography

By the middle of the nineteenth century, gas lamps illuminated city streets and new brick homes featured modern amenities such as indoor plumbing. Photographers set up shop in fashionable districts of major cities alongside artisans, retailers, bankers, and lawyers. Daguerreotype portraits were already less expensive than painted ones, and the invention of the wet collodion process in 1851 meant that the inexhaustible desire for portraits that formed the core of the early photographic business became easier to satisfy. By 1865, Canada’s main business directory listed more than 360 photographers.

At this time, studios catered to a primarily middle- and upper-class clientele. Starting in 1854, the Livernois family operated several bustling studios in Quebec City, and for three generations they fuelled the craze for portraits through various means, including by selling photographs of Catholic religious figures to francophones. The studio of George William Ellisson (1827–c.1879), located in Quebec City’s upper town where many of the city’s artists were based, was popular within the anglophone community. William Notman (1826–1891), a recent Scottish immigrant, opened a studio in Montreal in 1856 that he operated with his sons until his death four decades later. The first Canadian photographer to achieve international renown, Notman also established franchises and partnerships across eastern Canada and in the northeastern United States. In 1876, Notman’s partner in Ottawa, William James Topley (1845–1930), bought out Notman and ran the business until the end of the nineteenth century. The backbone of these photography studios was producing reliably proficient portraits at a reasonable price.

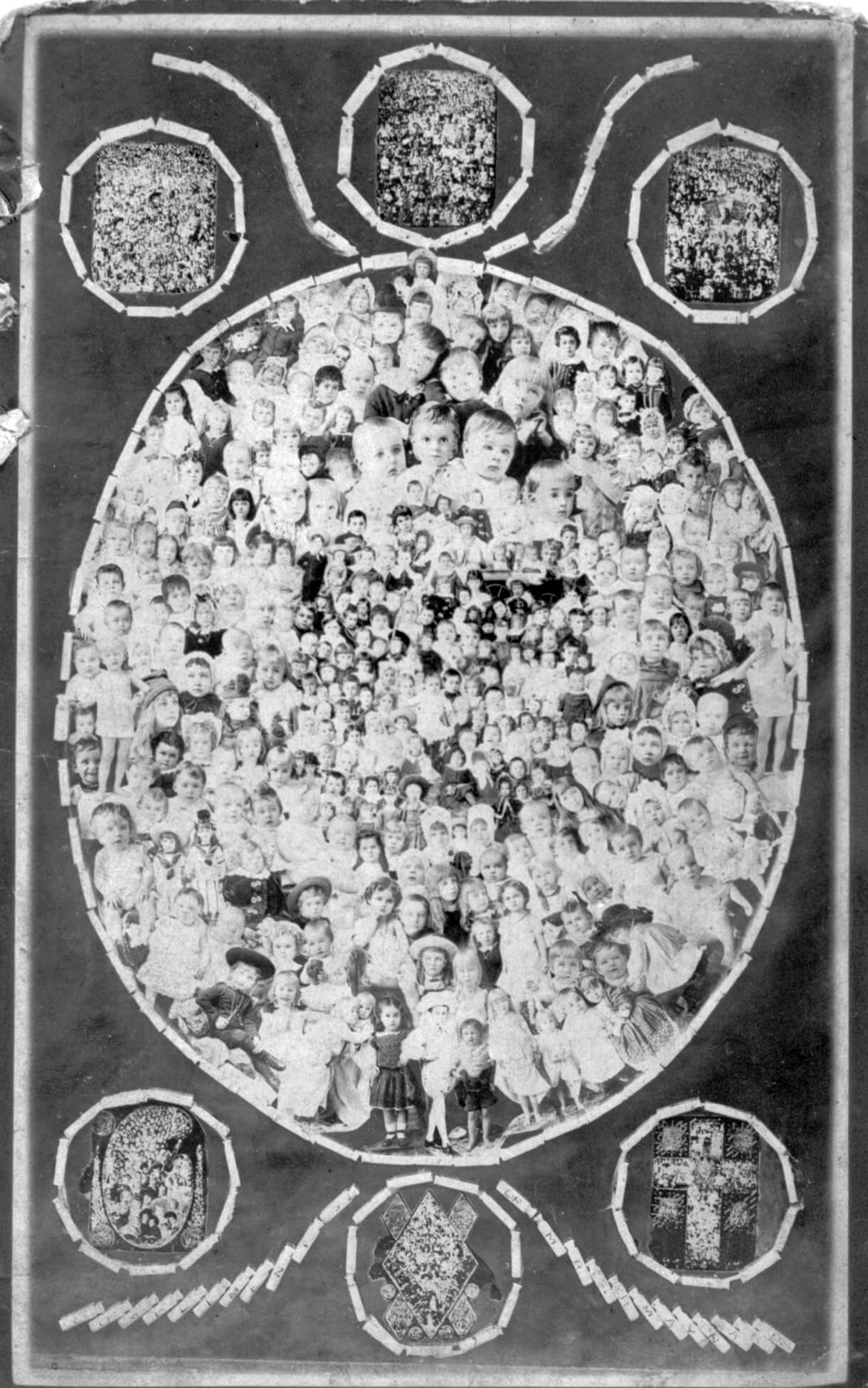

Women were involved in all aspects of the photography business. At the Livernois Studio, Élise L’Hérault dit L’Heureux (1827–1896), the wife of Jules-Isaïe Benoît Livernois (1830–1865), ran the family studio after her husband’s early death in 1865, and Notman’s female employees worked with clients, as well as making and touching up prints. In Ottawa, Alvira Lockwood (1842–1925) ran a successful studio from the early 1860s until 1884, and British immigrant Hannah Maynard (1834–1918) opened one of the first photography studios in Victoria in 1862. She served as its manager and primary photographer, with some participation from her husband, while also caring for her children. Maynard created inventive new formats to market photographs of children, such as her Gems of British Columbia, 1881–95, which brought her success and recognition in western Canada and in the United States.

Many of these early photographic studios produced and marketed a wide variety of formats and regularly updated their offerings to appeal to clientele eager for novelties. The carte-de-visite, a small photographic portrait in the form of a visiting card, was one such novelty that became popular in the late 1850s and formed the basis of many social interactions. People bought portraits in significant numbers to exchange with family and friends. Most portraits were prosaic, but that did not limit how studio owners marketed themselves. They created street-level window displays and turned elegant reception areas into portrait galleries that enticed potential clientele with rotating sample images of glamorous and celebrity sitters. The gallery and waiting room of the Livernois Studio in Quebec City, for example, was an elaborately decorated setting where clients could peruse an array of photographs available for sale while waiting to sit for their own portraits.

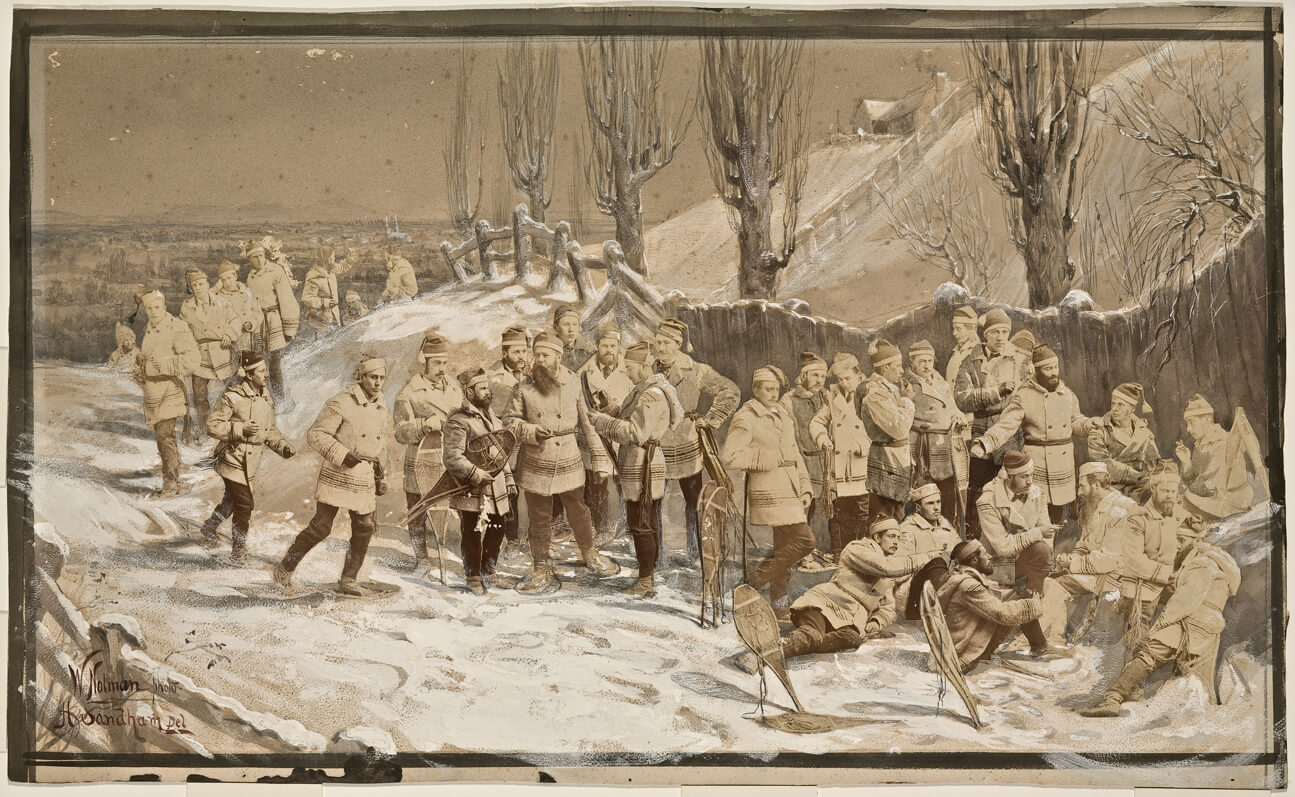

In Montreal, Notman generated several creative ways to attract sitters for regular portraits, including holding art exhibitions in his main studio. In addition to emphasizing the need for albums and the ritual of marking family events such as births and marriages with a photograph, Notman also pioneered group and composite portraits. He partnered with universities, professional groups, and recreational organizations to offer images that pictured the emerging social networks of the growing nation. Using newspaper ads, Notman invited attendees at society balls into his studio to sit in their finery for individual portraits that would then be grafted into a large composite arrangement. These composites would be photographed for display and sale. Notman’s studio also developed a storage system for portraits that allowed patrons to reorder copies of their own images or even to order images of other people. These “picture books” contained copies of every carte-de-visite taken at his studio, and the “index books” contained an alphabetical list of all his sitters and the numbers for the portrait negatives.

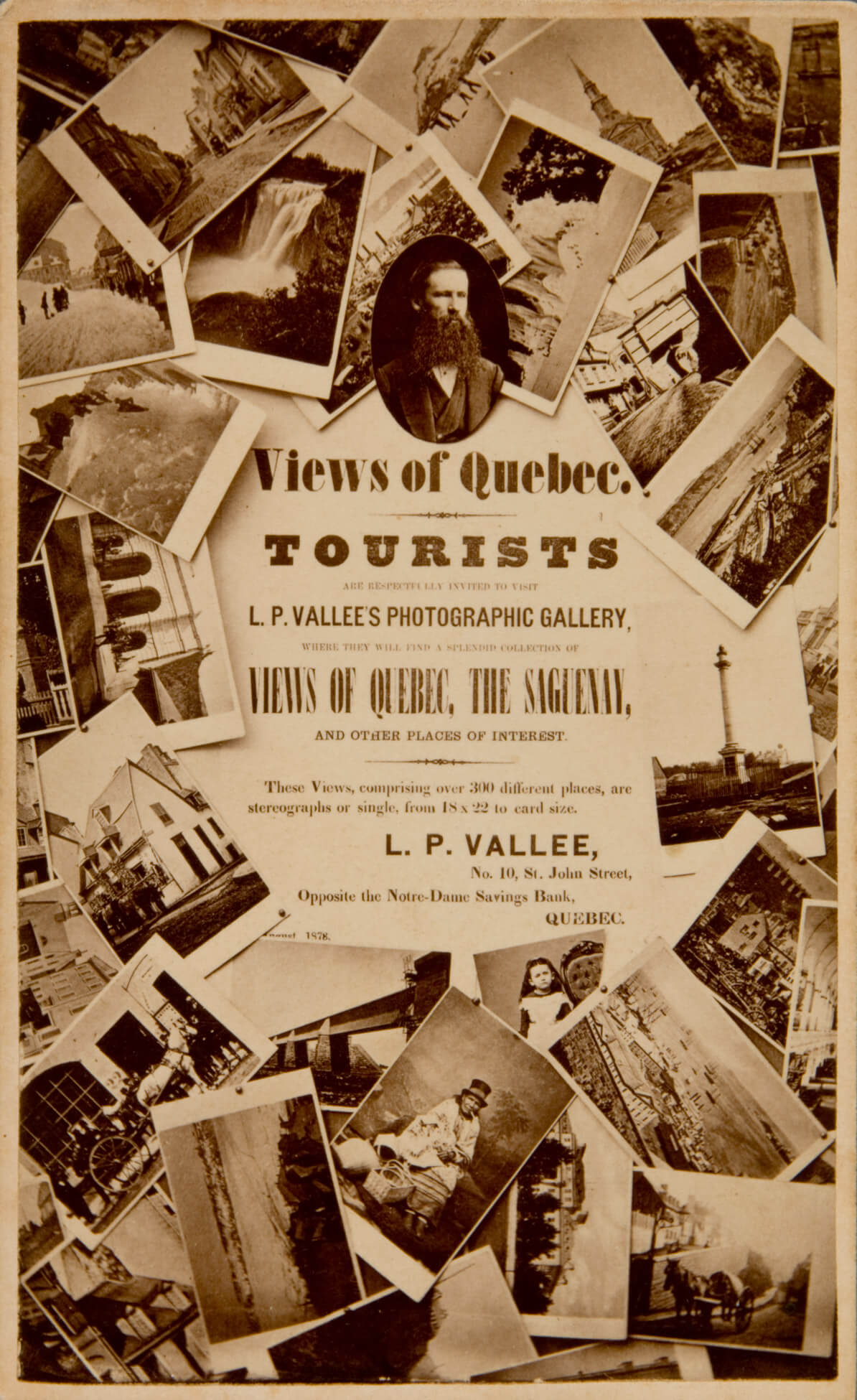

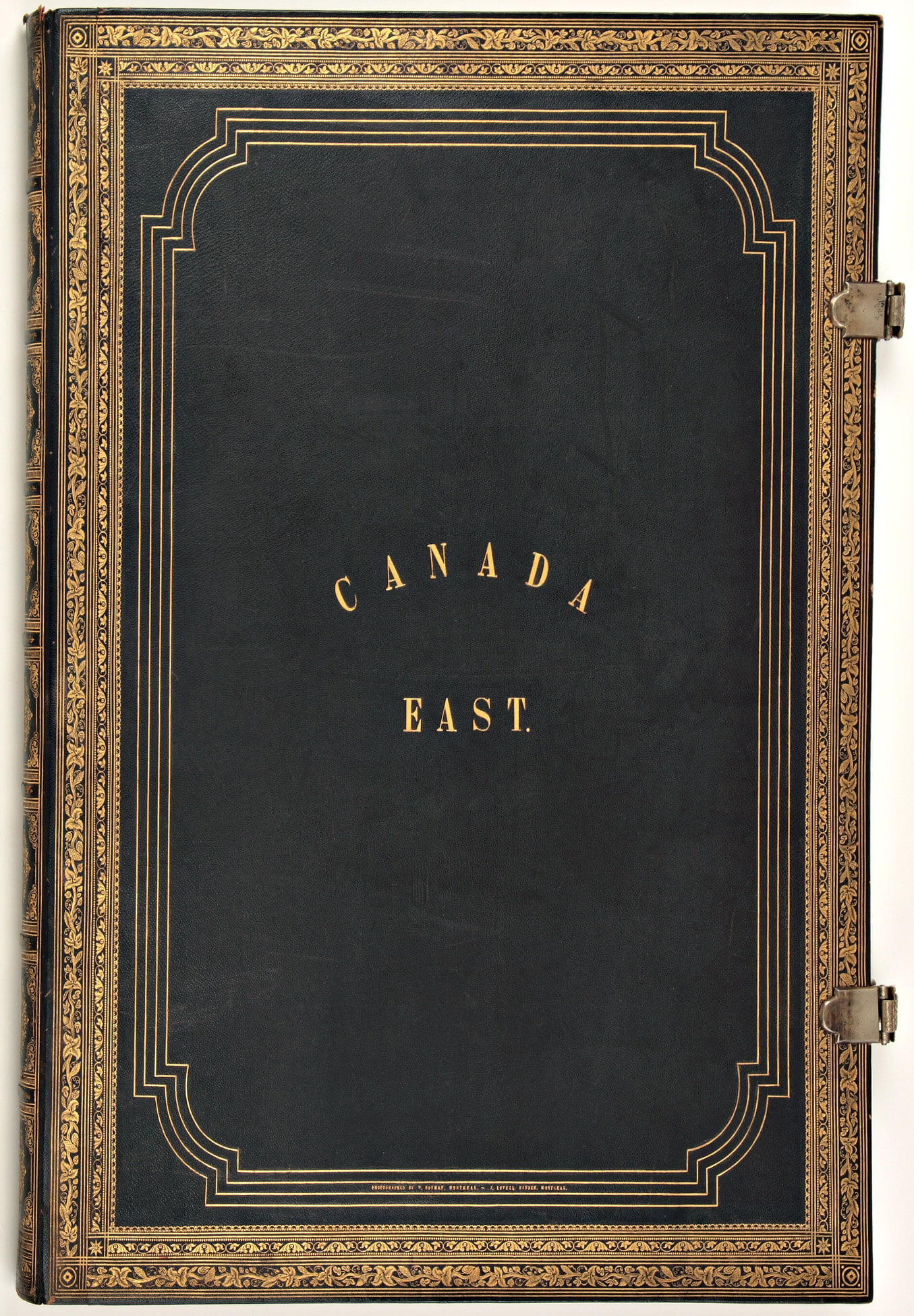

Successful studios built up a range of photographic products, including prints and albums, to sell to local patrons, tourists, government officials, and British military personnel stationed in Canada. Landscape and architectural views were especially popular as souvenirs. Some were sold as individual images and others were assembled into portfolios and albums, and later as illustrated books. The first Canadian portfolio, made by Samuel McLaughlin (1826–1914) and issued monthly, was called The Photographic Portfolio (1858–60) and included views in and around Quebec. Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905), who was also working in Quebec City, became well known for the impressive array of picturesque views that he marketed and sold to tourists visiting the region.

Most commercial studios offered a selection of their own images of local scenery for sale but would often collaborate with other studios in other parts of the country to ensure broader coverage of Canadian scenes. Stereographs were popular among tourists and locals who frequented commercial studios because they transported viewers to remarkable and distant locales. Scenic photographs were also featured in presentation albums, and in 1860 William Notman created an unusually elaborate offering. He gave to the Prince of Wales and Queen Victoria a maple box containing a leather-bound album of over five hundred printed photographs and stereographs of Canadian cities and landscapes, including Hamilton and Niagara Falls. Not one to miss a promotional opportunity, Notman listed stereograph copies of all the photographic images in Queen Victoria’s album for sale in his catalogue that same year.

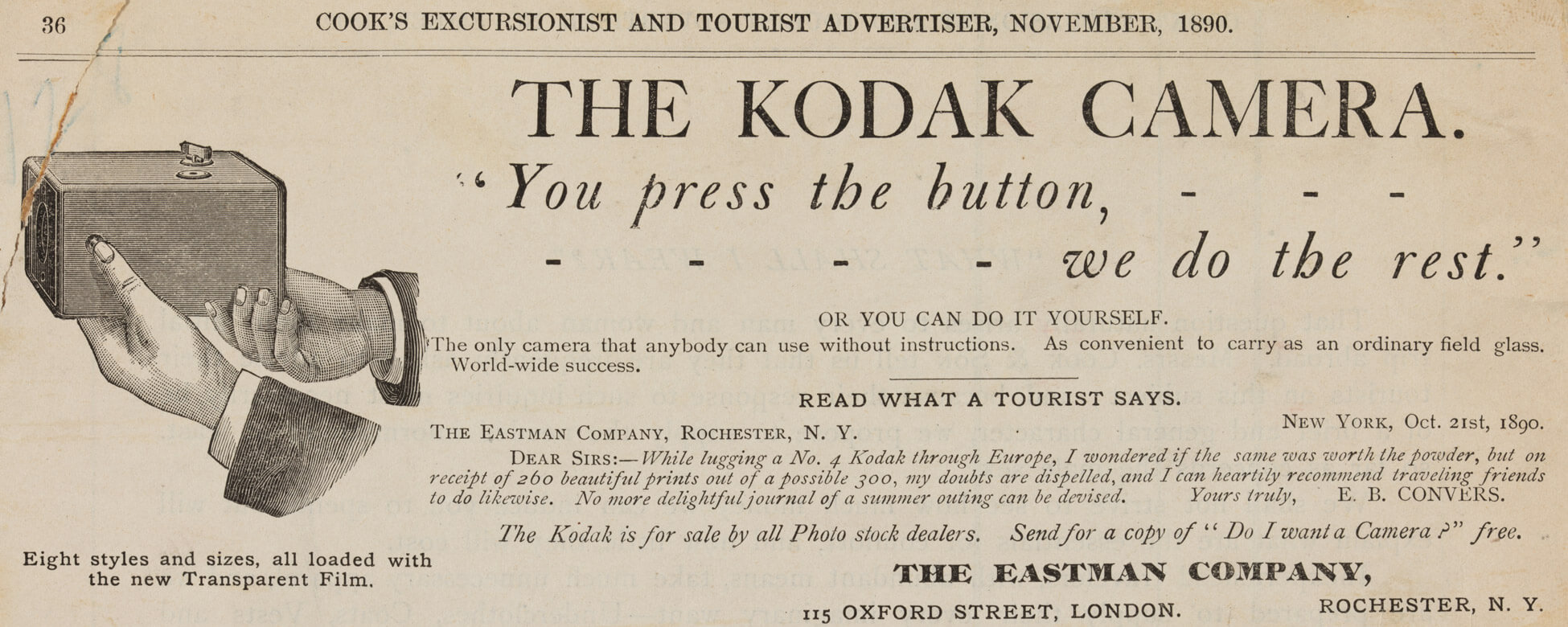

During the second half of the nineteenth century, photographic equipment companies worked to streamline and simplify the practice of photography, making it more accessible for both professionals and amateurs. Camera operators learned their craft from articles and Q & As with experts published in photography journals, some of which were produced by companies that sold photographic equipment in international journals that circulated in Canada. When George Eastman founded Kodak in 1888, he revolutionized photography with the invention of an easy-to-use camera that was preloaded with roll film that could be sent to Rochester, New York, for developing. Eastman advertised directly to consumers through popular magazines with the slogan “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest.” By the 1890s, the business hub of the industry had shifted from studios to manufacturers of photographic equipment and chemicals, although many studios were still in operation.

1850–1870s: Building a Nation

In the years leading up to Confederation, the population in the Province of Canada was spread out across a vast expanse of land, and people lived different lives depending on culture, religion, education, and occupation. Many Indigenous people maintained traditional ways of life on their ancestral territories, even as settlers cleared forests and cultivated crops on those same lands. Meanwhile, industry transformed urban areas, and railways and shipping canals opened new markets for manufactured goods. Political reforms shifted power away from Britain, and politicians in the settler-colonial government focused on trade and prosperity.

During the 1850s, photography was integrated into all facets of life, and government officials used photography to produce records in the service of dispossessing Indigenous peoples in the West. Specifically, the government was preparing for westward expansion by organizing expeditions and geological surveys. These expeditions and surveys relied on emerging beliefs about the value of photography as evidence, and their use as documents imbued photographs with the authority of “truth.”

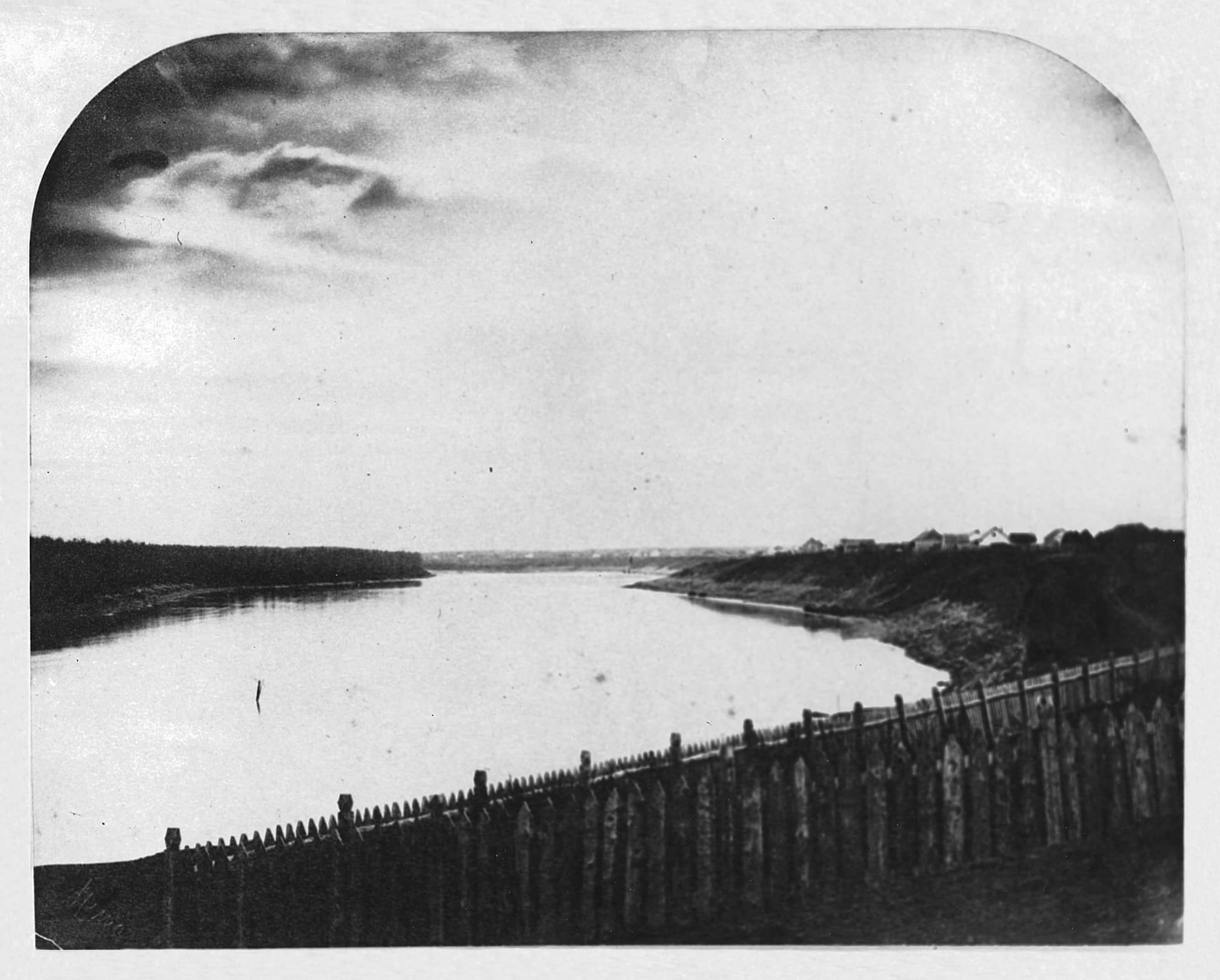

The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), established in 1842 as one of the country’s first scientific organizations, aimed to develop the mining industry and promote European settlement. The 1858 Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition led by Henry Youle Hind (1823–1908) was the first to use photography. Despite the challenges of working with the wet collodion process in the field, the expedition’s photographer Humphrey Lloyd Hime (1833–1903) made portraits of Indigenous people, along with a series of landscape views of the route, in settlements, and at Hudson’s Bay Company outposts.

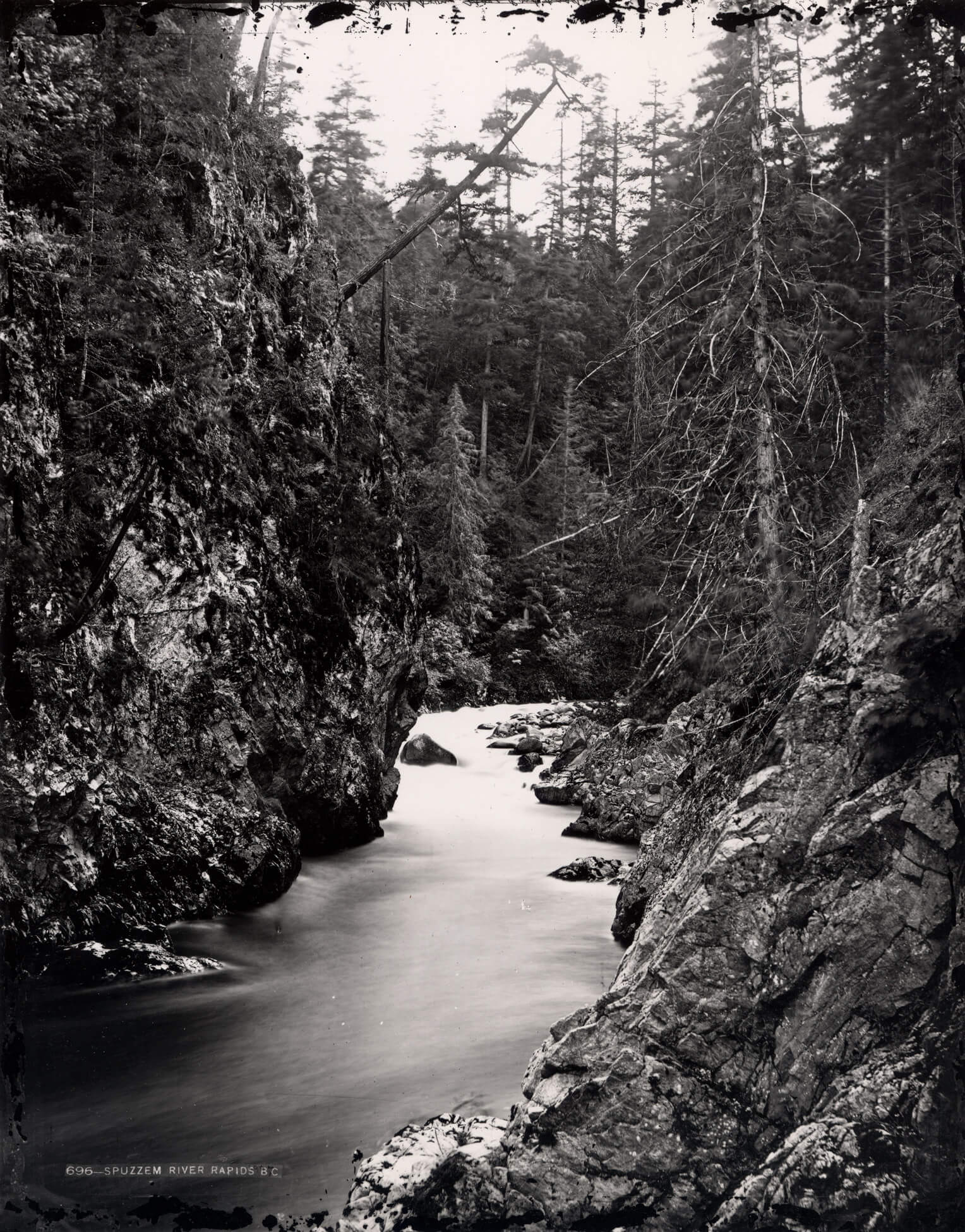

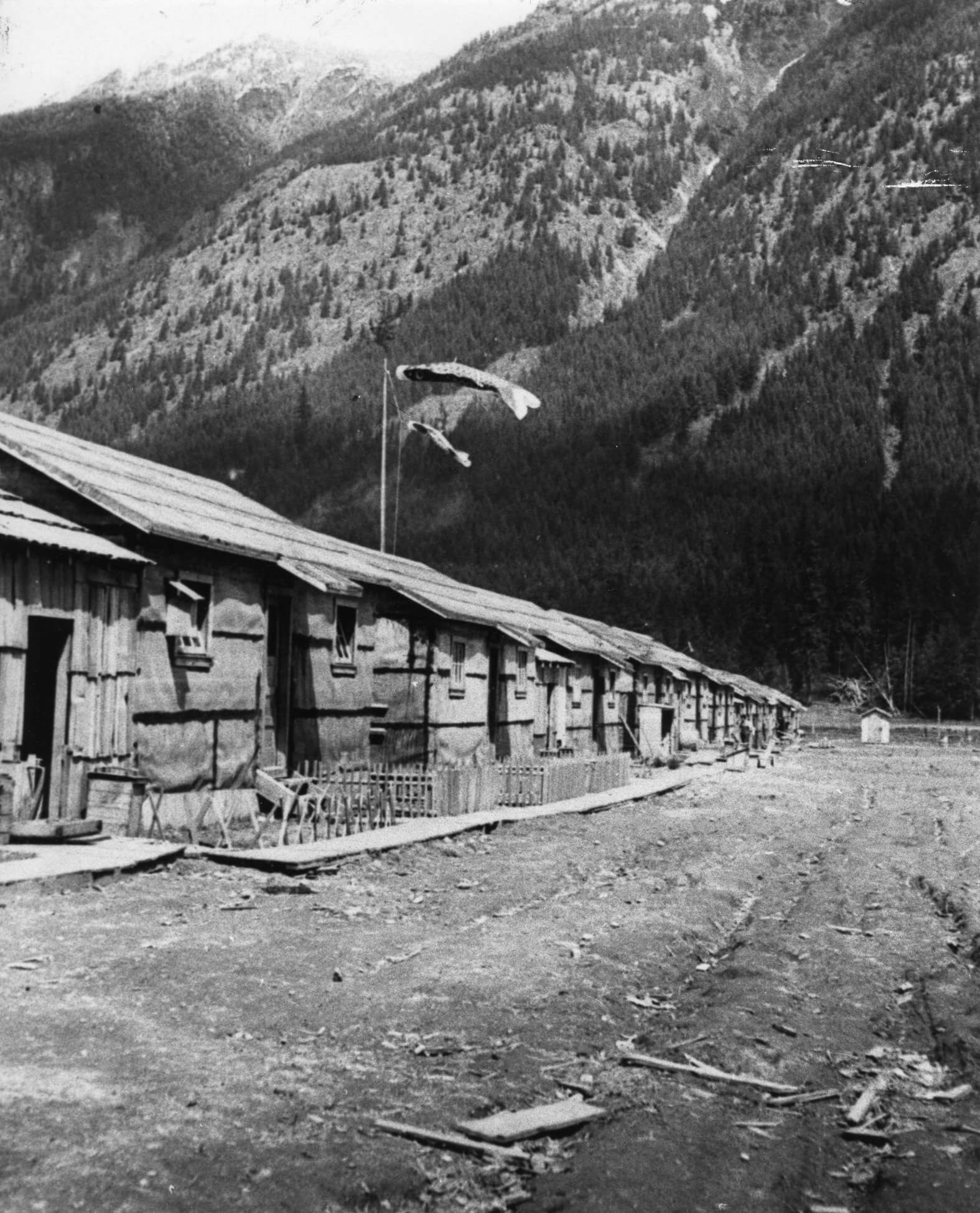

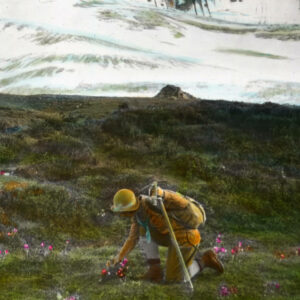

In 1871, Benjamin Baltzly (1835–1883) photographed landscapes and waterways for a geological survey led by Alfred R.C. Selwyn along the North Thompson River in British Columbia. Baltzly was employed by Notman, and his images of the B.C. interior were sold to clients in the East who were interested in the terrain of the West, which was unfamiliar to them. Over the following decades, government expeditions and surveys continued to produce photographs in support of a colonial idea of the West as rich in resources but largely uninhabited and therefore available for development by settlers. By the 1910s, photography was so integral to the work of the GSC that there were two full-time technicians processing the thousands of films and plates that topographers brought back from the field.

Photography was used by the settler-colonial government to demarcate and claim territory. Even when photographs were not essential to the process of surveying and mapping an area, photography was used to record that work. Between 1858 and 1862, the British sent two units of Royal Engineers to B.C. to produce a boundary survey marking the border with the United States. The surveyors cut a line through the forest along the 49th parallel as they mapped and photographed the terrain. These surveys, which continued in the 1870s, sought to rationalize and standardize the natural environment to assert control and render it manageable. The survey photographs were even used to settle a land dispute with the Americans.

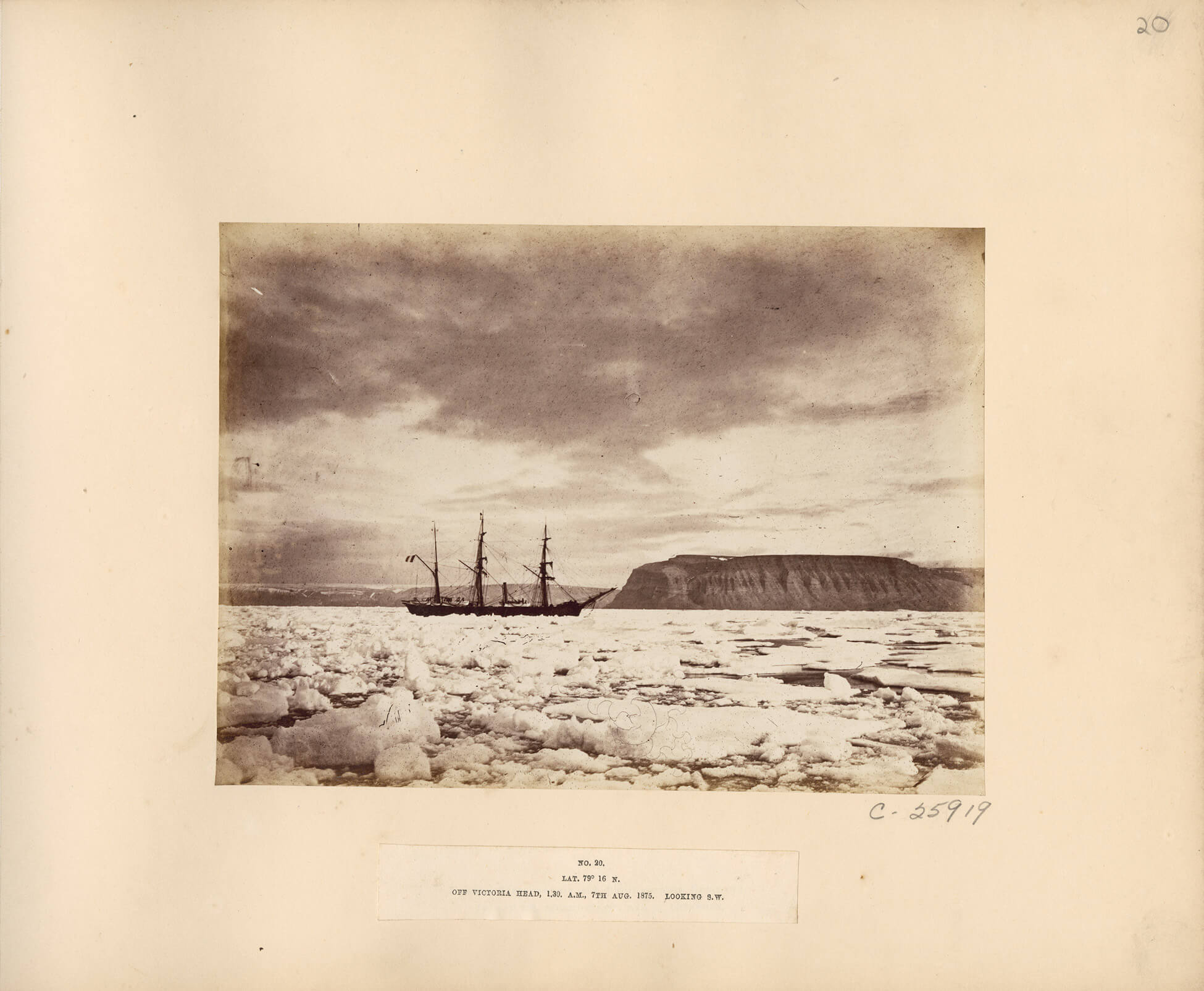

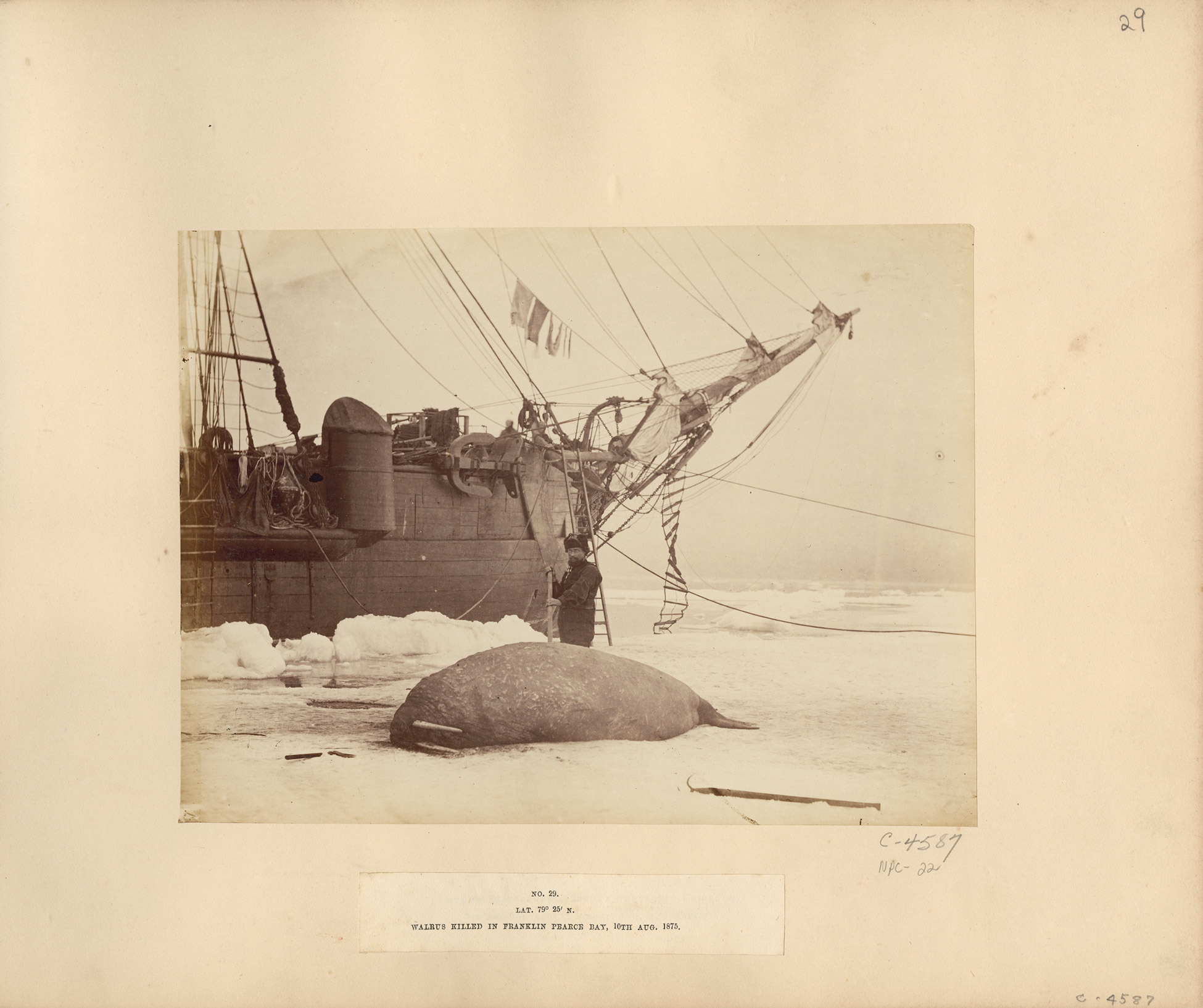

Also notable at this time is the crucial role photography played in exploration. Although written accounts were still considered the best way to convey the emotional challenges of an expedition, as the following examples show, photography was embraced as a tool for recording events and communicating discoveries. In 1857, the French naval officer Paul-Émile Miot (1827–1900) produced some of the earliest photographs of Newfoundland, Cape Breton Island, and the French islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, located south of Newfoundland. Miot’s work was used in hydrographic surveys, and select photographs were reproduced as woodcuts in French and American magazines. Photographs made on Arctic expeditions, such as those by Thomas Mitchell and George White for the British Arctic Expedition of 1875–76, record topographic features and give an account of the conditions. Captain George Nares described the results as forming “a photographic history” of the expedition, and it became standard practice to use photography on subsequent Arctic voyages. Eventually, Nares presented a portfolio of photographs from the trip to Queen Victoria, who was an avid collector of photography.

As another aspect of nation building, the settler-colonial government began to commission photographic documentation of major infrastructure projects. In many cases, these photographs were made to monitor progress and to demonstrate the ambitious nature of the work. Samuel McLaughlin was appointed the first official photographer for the Province of Canada in 1861, and in this role, he documented the construction of numerous public works projects, most notably the Parliament Buildings. When the Prince of Wales visited Canada in 1860, he was presented with an album of McLaughlin’s photographs to highlight the colonial ties between the Province of Canada and the British Empire. Photographic documentation of construction ensured accountability and responsible government, as well as portraying the progress of nation building.

During this period, one of the government’s key concerns was improving transportation infrastructure to promote economic development. With the support of politicians in the colony, the British-owned Grand Trunk Railway Company began building a stretch of track between Toronto and Montreal in 1852, and this was soon extended south of Montreal. The company then constructed Victoria Bridge over the St. Lawrence River to link the island of Montreal to the south shore, which improved access to the U.S. market.

The bridge was considered a triumph of engineering, and William Notman was commissioned to photograph its construction. His series from 1858–60 depicts the heavy machinery and elaborate scaffolding used to build the vast, tubular structure, and in some photographs, such as Framework of tube and staging no. 8, Victoria Bridge, Montreal, QC, 1859, labourers appear as small figures amid the imposing beams. Notman included a selection of stereographs of the bridge in a series of views that caught the attention of Britain’s acclaimed Art Journal. His photographs conveyed the promise of industrial expansion and helped to build support for future development.

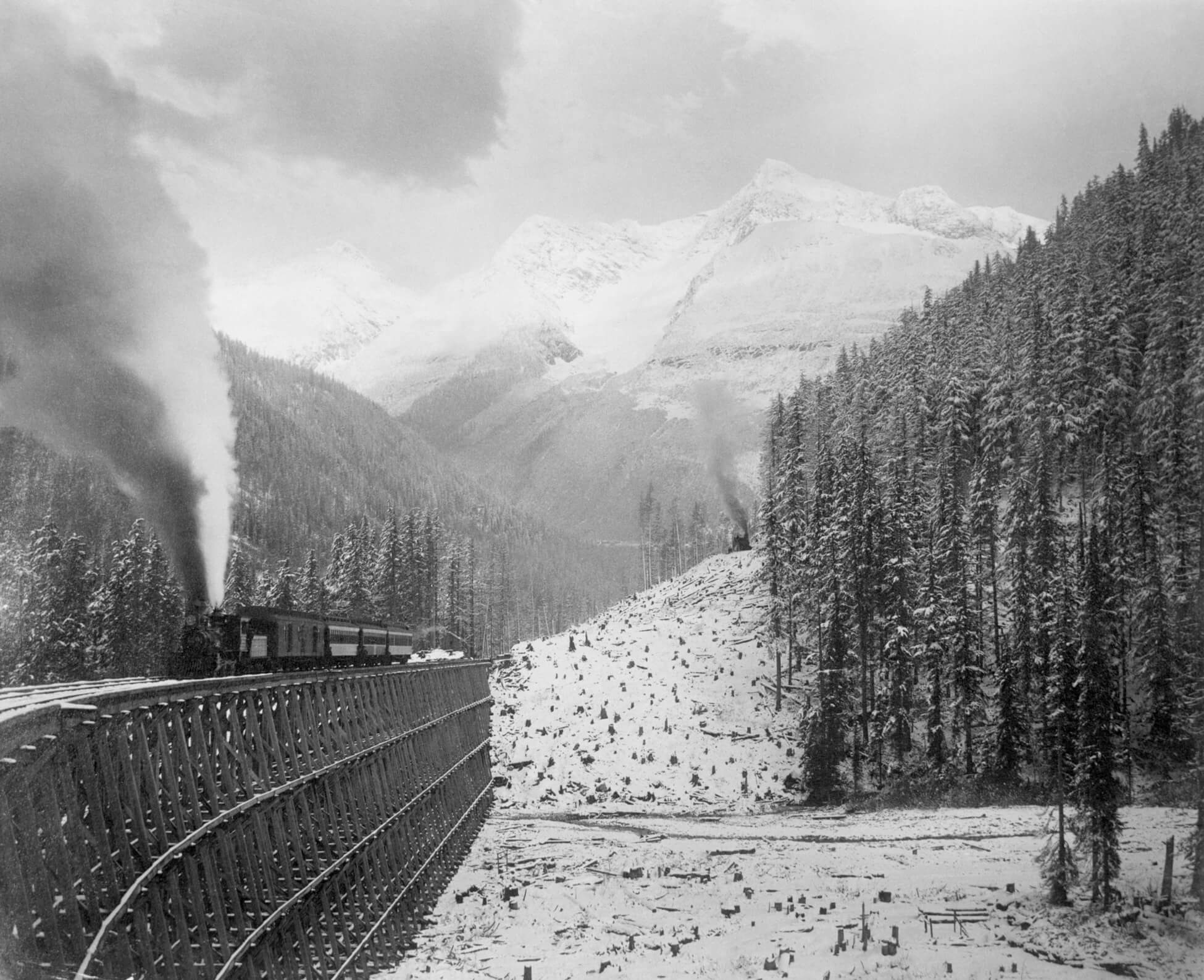

Photographs of transportation infrastructure of the 1850s made it possible for citizens to imagine Canada as a nation. Indeed, British Columbia agreed to join the Dominion of Canada in 1871 because of the federal government’s promise to build a link to the transnational railway, although it was not until the 1880s that a transcontinental railway connected eastern Canada to the west coast. The famous photograph by Alexander Ross (1889–1978) of Hon. Donald Smith driving the last spike marked the completion of the railway and the fulfillment of that promise. During this time, photographs for the Canadian Pacific Railway survey by Charles George Horetzky (1838–1900) were some of the first to depict the Northwest Territories and parts of the British Columbia interior.

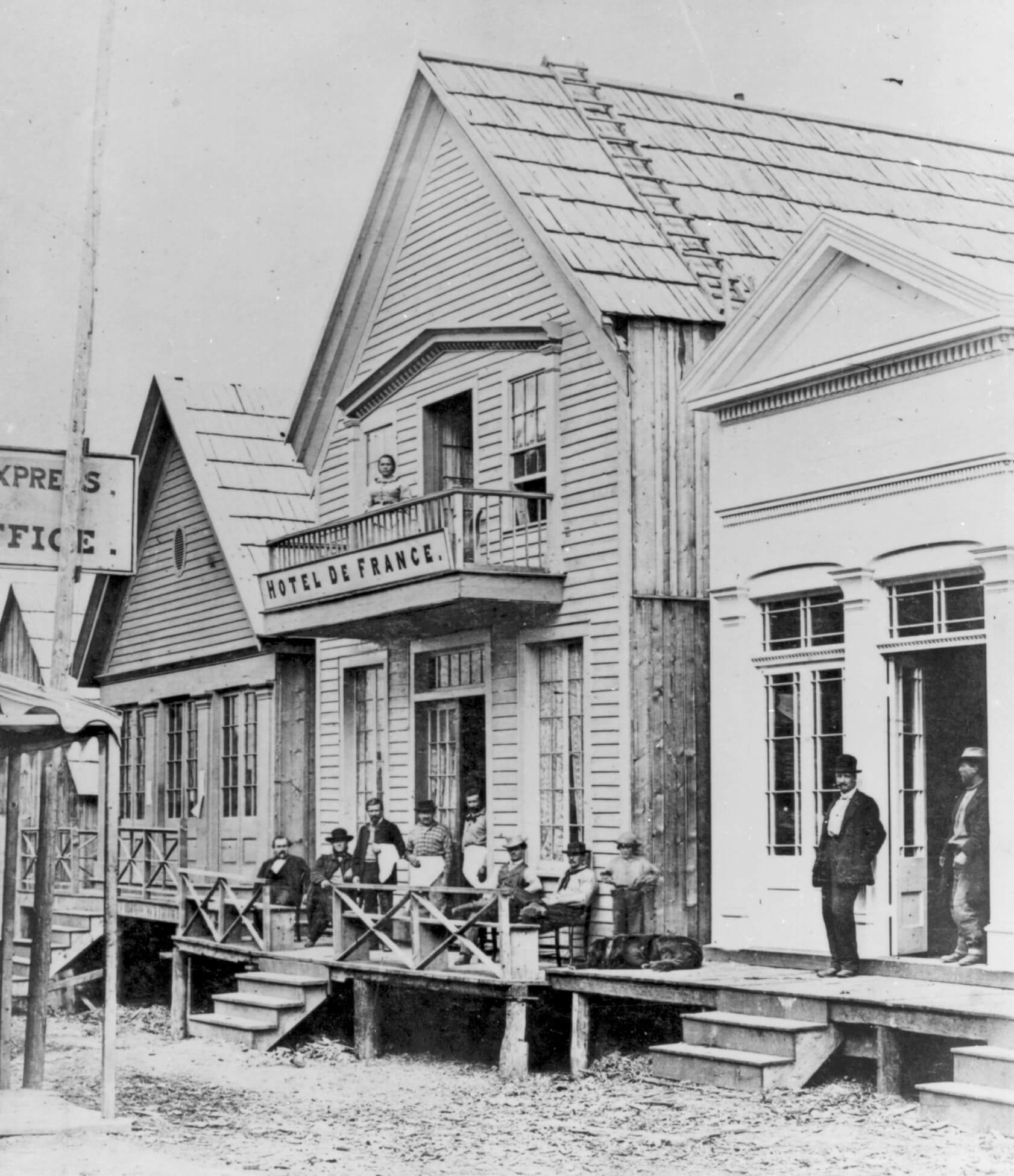

Commercial involvement in photography grew alongside and intersected with its use by the settler-colonial government. In the late 1850s, photographers highlighted in their work the productivity and success of colonial settlements and the potential for future development. Their landscape views and street scenes promoted the success of the colony to loved ones back home, shaping the way the country and the West were imagined, and influencing settlement patterns. Images of the gold rush in the Cariboo Mountains made by photographers such as Charles Gentile (1835–1893) and Frederick Dally (1838–1914) were published widely in newspapers and immigration literature and attracted newcomers to the region, including many Americans. Mining settlements, in particular, symbolized the region’s rich natural resources and signalled the potential for prosperity and expansion.

During this crucial period, commercial and bureaucratic photography was used to subjugate Indigenous peoples and cultures in the service of building a new settler-colonial nation. Although Indigenous peoples opposed the expropriation of land and the extraction of resources by settlers, these conflicts were mainly described in textual accounts and were not often photographed. Even when Indigenous peoples’ resistance was photographed, settlers interpreted this as evidence that Indigenous peoples were unable to adapt to modern life. Today, it is important to recognize that this assumption about adaptation is incorrect and Indigenous cultures were able to transform and revitalize, even as they experienced many negative effects of contact with Europeans.

1860–1900s: Collecting Photographs and Creating Albums

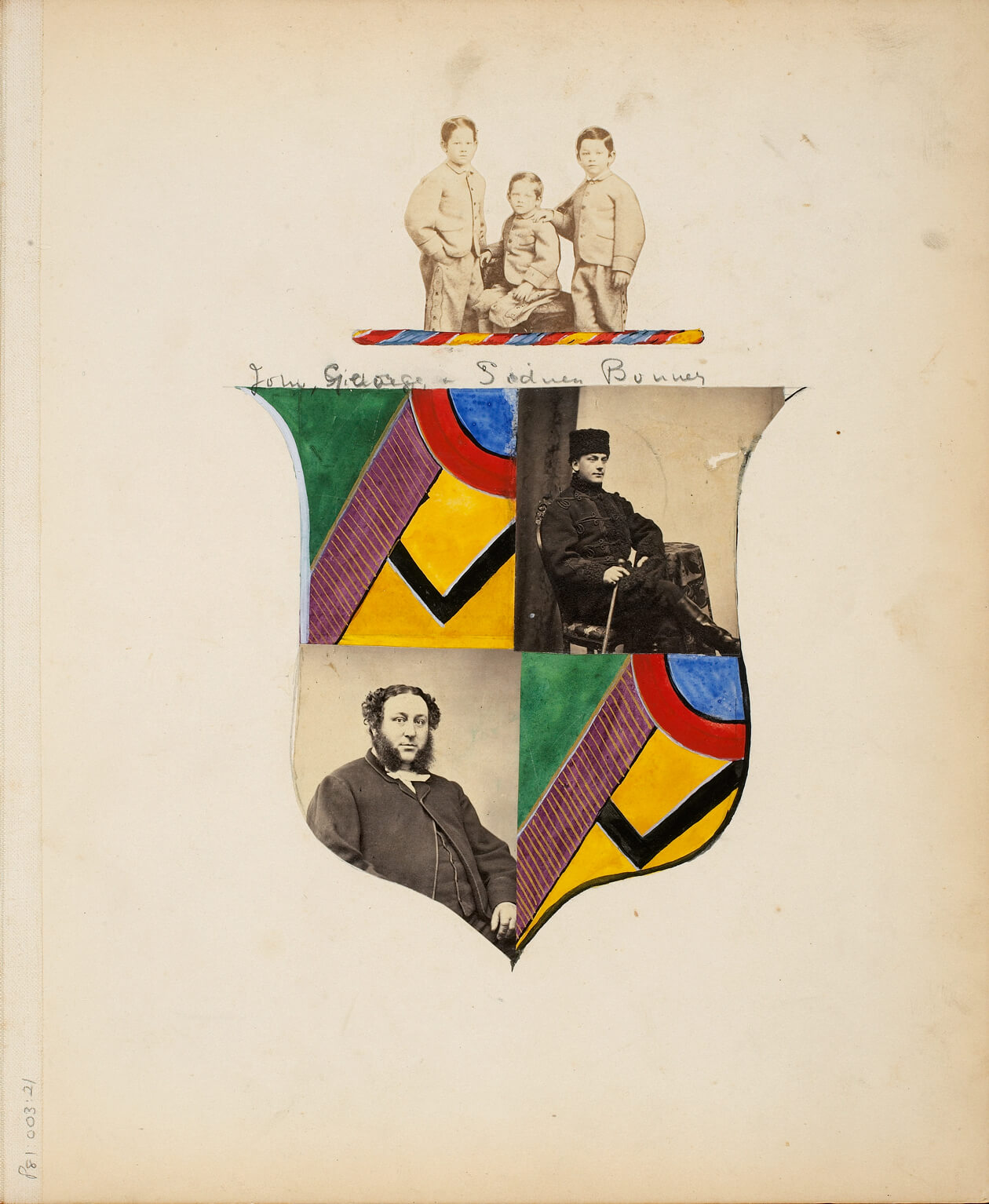

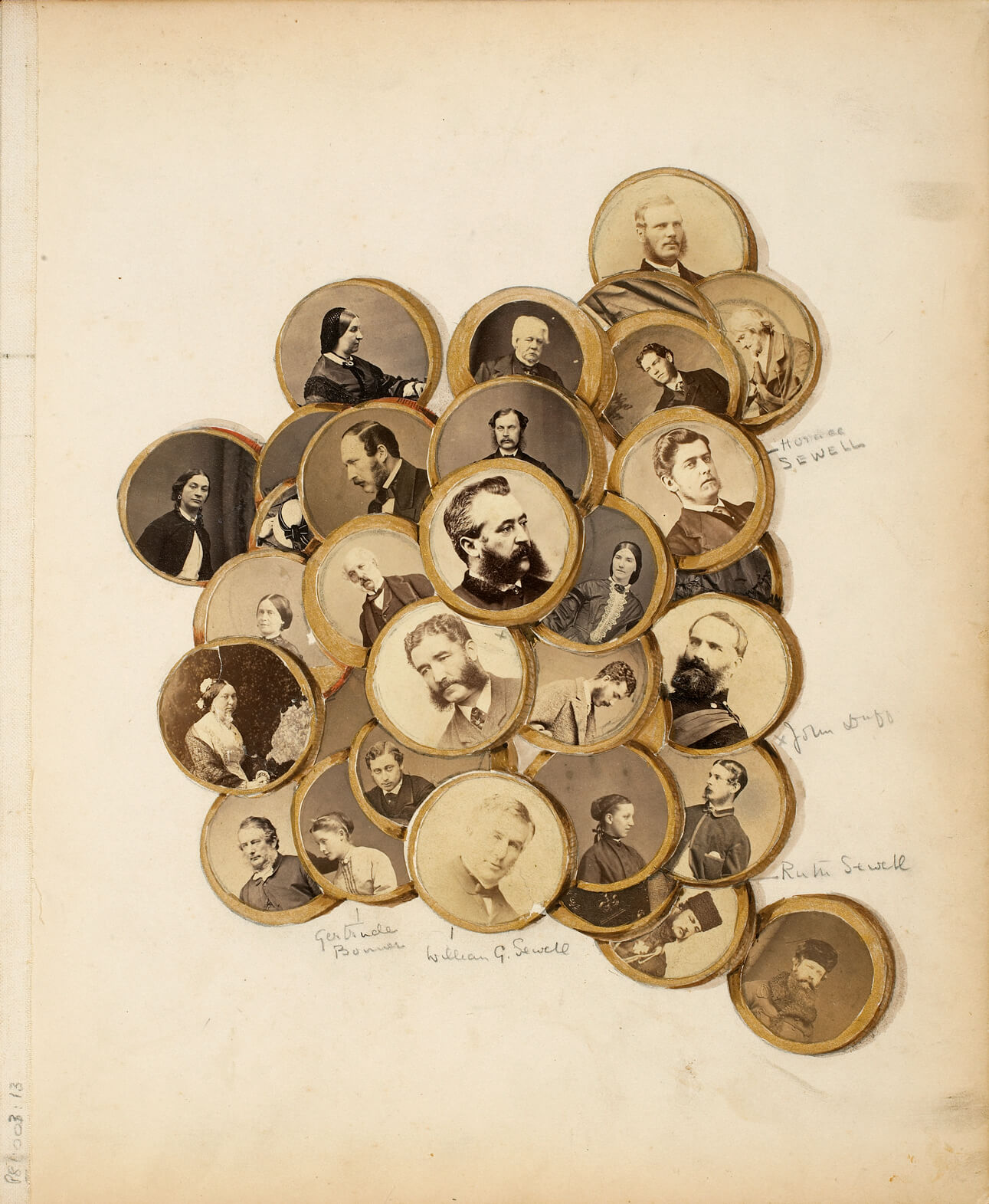

Amid the nation building and economic development of the late twentieth century in Canada, there were many opportunities for people to consume, collect, and eventually take their own photographs. Collecting and archiving photographs into albums was a powerful way to create narratives about family and social networks, and a popular activity for middle- and upper-class women in the nineteenth century. In one album from the 1880s, photographs of the Bonner family were incorporated into the form of a crest to express the personalities of individual sitters and the status and relationships between family members. In another instance, a grape-like cluster of circular cut-out portraits conveys a network of connections surrounding two men, Horace Sewell and John Duff, who appear at the centre and on the top of the collection of images.

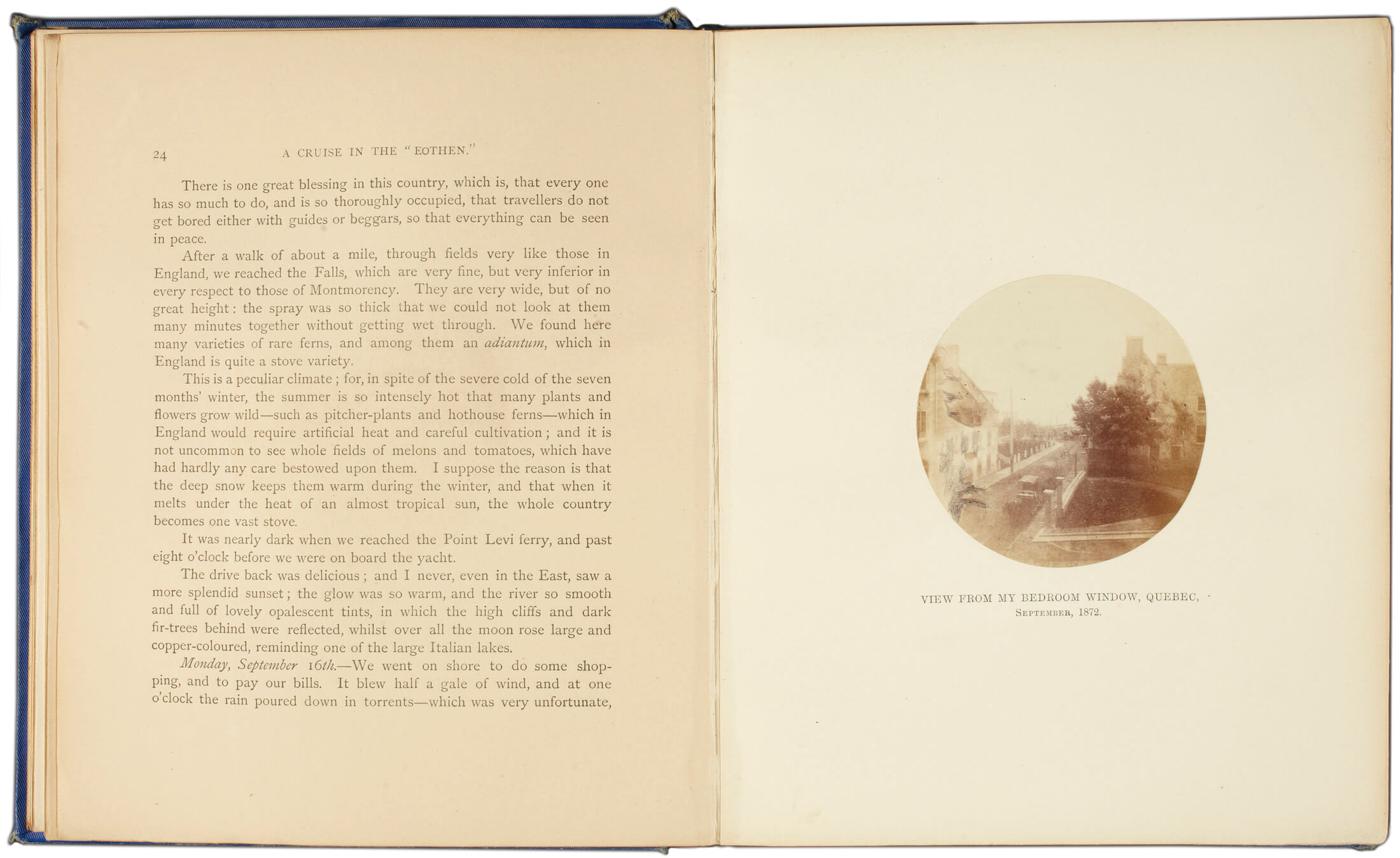

Personal photographic albums were also a means of normalizing settler-colonial beliefs about the new country of Canada while denying the violence of the encounter. In 1872, Lady Annie Brassey (1839–1887) and her family travelled by private yacht from England, exploring the Maritimes before travelling up the St. Lawrence River to visit Montreal and on to Toronto and the all-important tourist destination of Niagara Falls. This journey was one of many that Brassey chronicled in albums and published books. In Canada, she collected city views and landscapes photographed by Alexander Henderson (1831–1913), and winter scenes made by William Notman. She commissioned portraits of herself and her travelling parties from Notman and a portrait of their yacht from Henderson. Brassey also made and developed her own photographs along the way. She described Canada as a fitting place for “emigration for our overflowing population,” and her albums pictured Canada through the lens of a settler colonist.

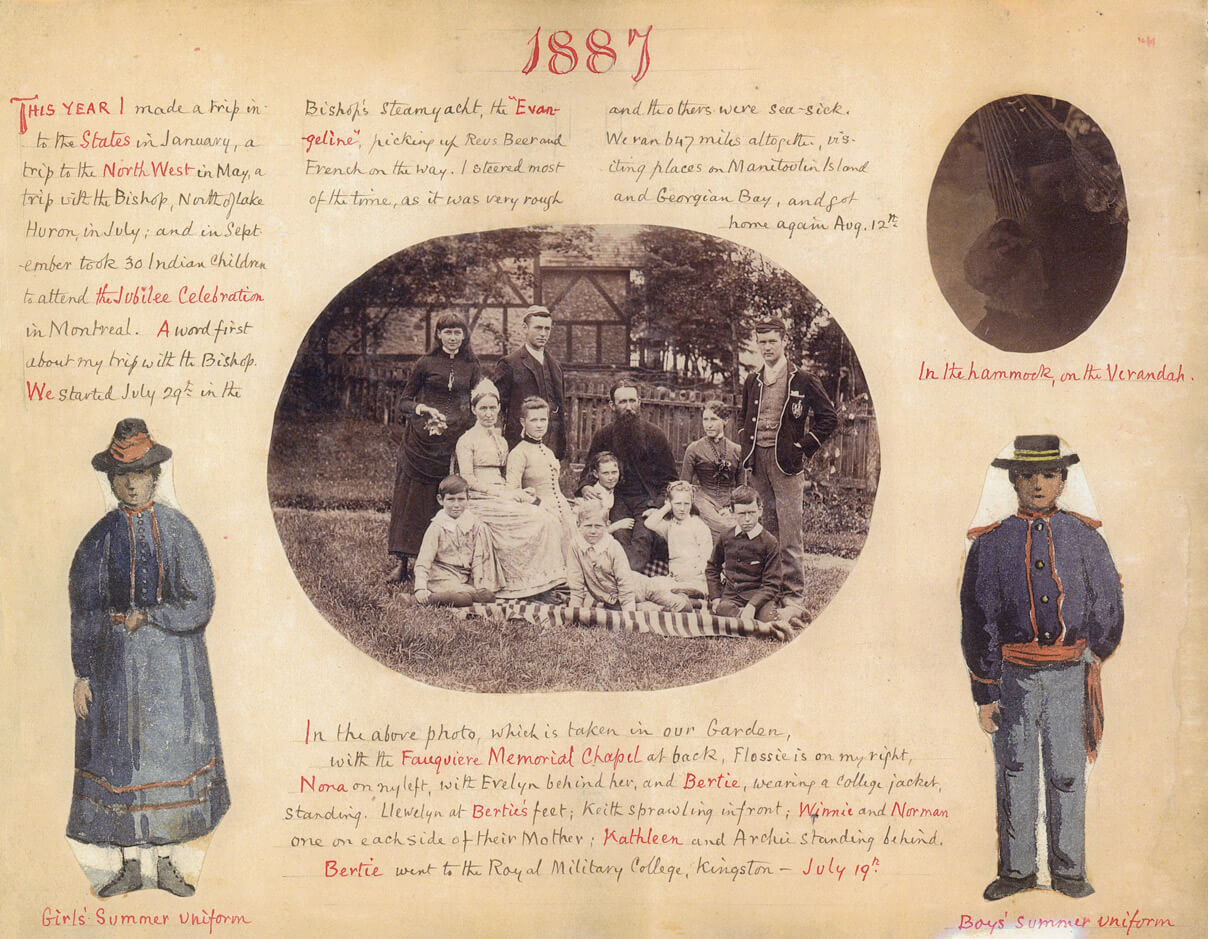

Similarly, in an album from 1868, Captain Astley Fellowes Terry (1840–1926) carefully arranged photographs of his time in Canada that contributed to an imaginary geography of the country as a burgeoning settlement. As in many other early Canadian travel albums, Terry included few images of Indigenous people and life, which reinforced the idea of a land of colonial possibility. But an album compiled by Reverend Edward F. Wilson, founding principal of Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie, tells a different colonial story.

Shingwauk Indian Residential School (IRS) was funded by the Anglican Church and the Canadian government and was described as an “industrial school,” in that children spent half days in lessons and the remaining time labouring for the IRS and its farming operation. The inscription at the front of Wilson’s album suggests the empty book was presented to him soon after the opening of the IRS in 1876. The photographs that Wilson collected and likely commissioned over fifteen years are mostly studio portraits of staff and children at the IRS, as well as those who had left the IRS; these pictures are visual reflections of the institution’s goal of assimilation. The children are dressed in formal Victorian outfits and cast as Christians in photographs that conceal the way the young subjects were forcibly separated from their families, communities, and cultures. The residential school system operated from 1828 until 1996, with a notably active period of building and expansion following the introduction of the Indian Act of 1876. As in other institutions in the system, children at Shingwauk IRS were exposed to abuse and neglect behind the carefully curated façade of propagandistic tools like Wilson’s album of “successful” conversions.

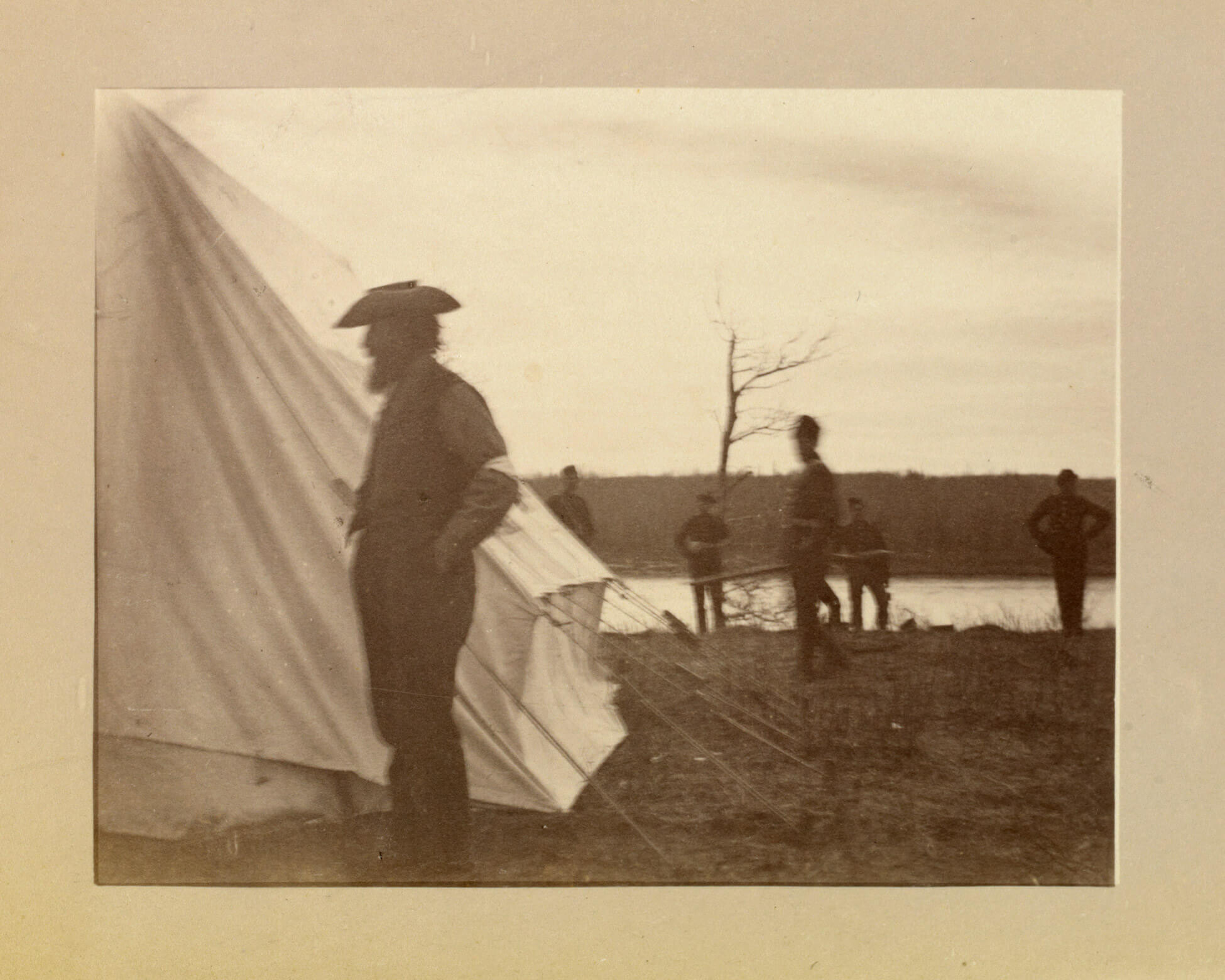

The arrival of dry plate film in the 1870s, followed by hand-held cameras in the 1880s, created radical new opportunities for more people to engage with photography, not by posing or collecting, but by taking their own photographs. Freed from having to cart burdensome equipment and no longer requiring technical expertise, many more people became photographers. Camera clubs and amateur photographers proliferated. One such person was Captain James Peters (1853–1927) of the Canadian Artillery, who was a member of a Quebec City camera club where he honed his skills using a twin-lens reflex camera with gelatin dry plates that could be shipped back to the manufacturer for developing.

Captain Peters was among the first in Canada to capture military activity in the line of duty. In 1884–85, he took his camera along when his unit was sent to Saskatchewan to fight the Riel Resistance. Although his photographs of Fish Creek and Batoche lack aesthetic appeal, they are notable as the first images taken during battle. Peters’s album includes a blurry image of Louis Riel before the Métis leader was hanged for treason. Although Peters had not intended to circulate the photographs, their importance as historical documents was quickly recognized. The British journal Amateur Photographer published a selection of the photos in 1885, and albums of approximately fifty photographs were issued as souvenirs of the Riel Resistance.

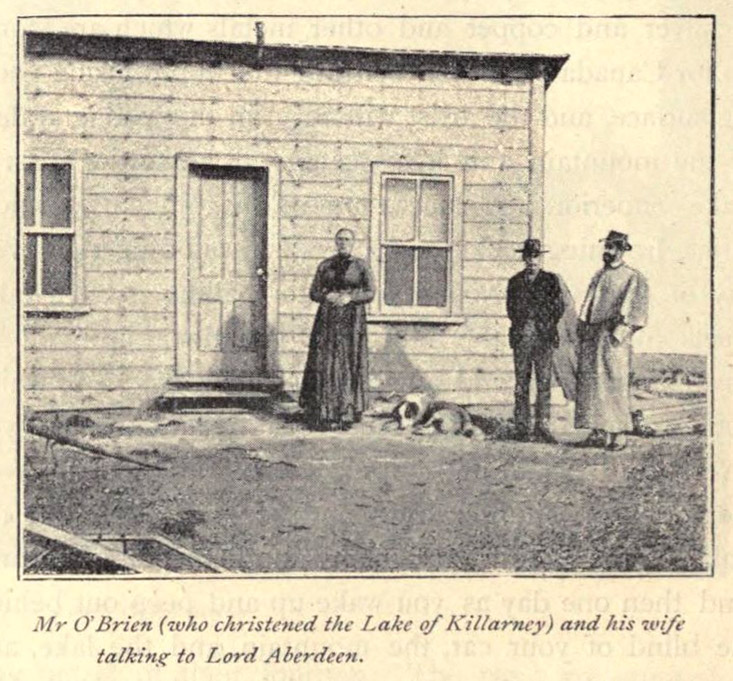

George Eastman, an American businessman, invented the Kodak camera in 1888, creating a proliferation of amateur photographers. Cameras that were lightweight and easy to operate also opened up new avenues for women to create their own records of domestic and public life. In Drummondville, Quebec, Annie McDougall used a hand-held camera to photograph her friends and family, while Scottish aristocrat and social reformer Lady Aberdeen (1857–1939) used an early iteration of the Kodak camera to document two trips across Canada, in 1890 and 1891. Through her Onward and Upward Association, Lady Aberdeen was committed to providing education and emigration opportunities to working-class women. Her Canadian tours were designed so she could visit with some of the women her organizations had helped to settle in the Prairies and to solicit advice for young women considering a move to Canada. The photographs taken by Lady Aberdeen served double duty in her extensive family albums and as illustrations for her publications, where they were used to make Canada seem more accessible to potential young British immigrants. The Canadian trips were featured as articles in the Association’s newsletter and then as a book, Through Canada with a Kodak (1893), published the same year her husband was appointed governor general of Canada.

Canadian women responded with enthusiasm to Kodak Girl advertisements that connected amateur female photographers with the ideal of liberated womanhood. Young women and girls embraced the simplicity of Kodak cameras and used them to photograph their recreational and social activities. The Toronto Girl Guides introduced a photographer’s badge in 1916 that Girl Guides could earn by demonstrating their knowledge of cameras and chemistry. A summer camp for girls in Algonquin Park hired its first counsellor of photography in 1911, and female college students compiled albums emphasizing sports and social activities.

With the popularity of Kodak photography as a leisure activity for women, some of the men who belonged to camera clubs and considered themselves serious photographers sought to distance themselves from the new craze. They did so by trying to distinguish themselves through technique and artistry. As the century drew to a close, amateur photographers of all kinds embraced the potential of new and easy-to-use processes and integrated photography into their daily lives.

1870s–1910s: The Rise of State Power and Capitalist Expansion

In the years after Confederation, in 1867, the new country of Canada grew to include Rupert’s Land, Manitoba, the Northwest Territories, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island. The population increased with an influx of immigrants from regions such as Scandinavia, and settlement in the West continued to encroach on Indigenous lands, resulting in conflicts such as the Red River Resistance and Riel Resistance. To counteract tensions between different cultural groups at this time, government unification projects included settlement programs and transportation infrastructure such as the transcontinental railway.

Photography contributed to the expansion of government when it was adopted as a technique of documentation and a form of evidence following the introduction of the dry plate process in the 1870s. Within government institutions, the medical sciences, and the social sciences, photography played a pivotal role in negotiating claims to power and as a method of surveillance.

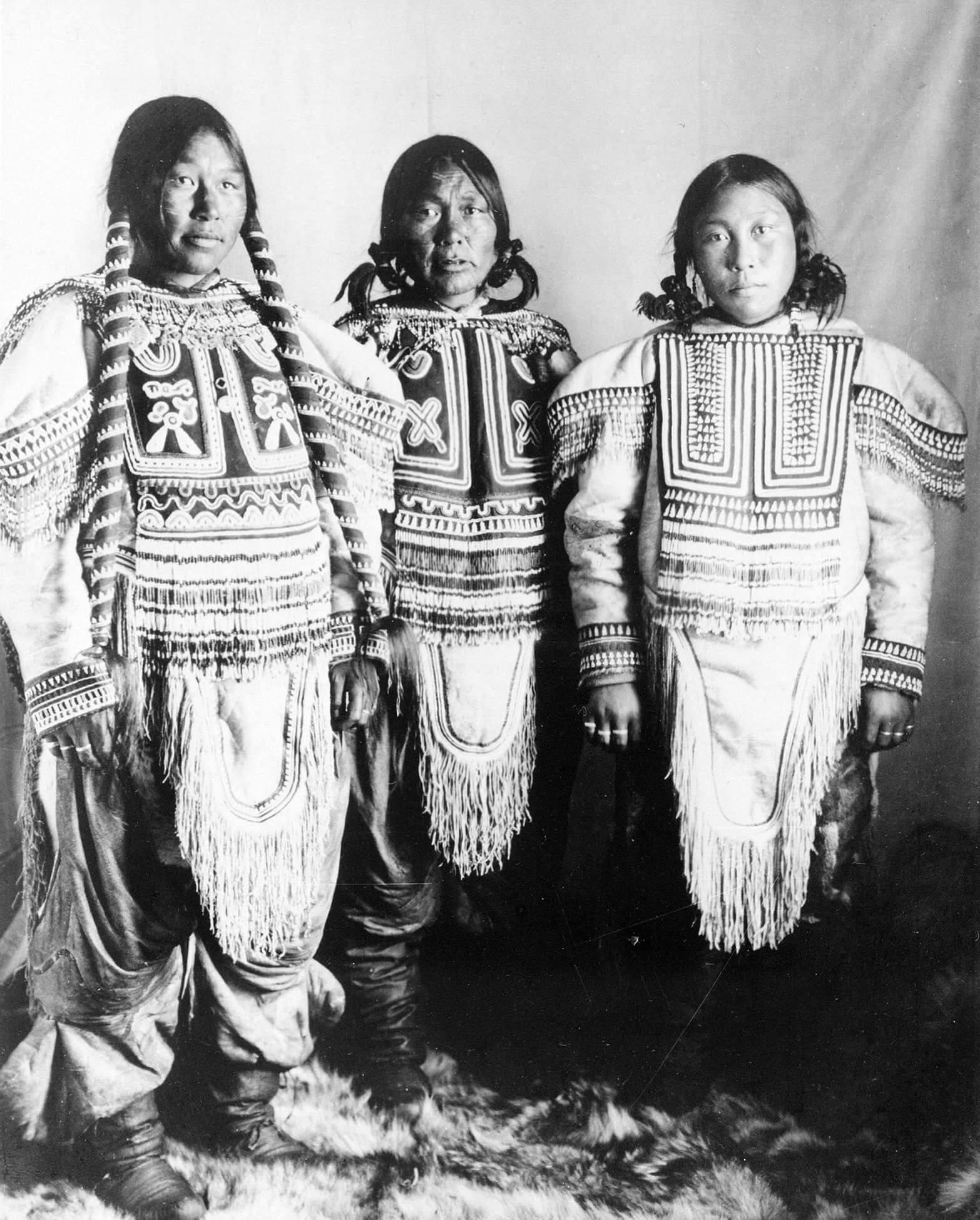

By the 1870s, the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) was using photography extensively to explore and map the country, including to determine the route for the transcontinental railway, sites for resource development, and locations for settlers. Although geologists and surveyors set out to photograph topographical and geological features of land, many also turned their cameras on Indigenous inhabitants. George Mercer Dawson (1849–1901), a GSC geologist, photographed Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands) in 1876 and 1878. Dawson was especially interested in the Haida, and in addition to his own work, was a supporter of German American anthropologist Franz Boas, whose theory of cultural relativism discredited the idea that European culture was superior. Nonetheless, Dawson persisted in making photographs even though the Indigenous people he encountered were resistant and often did not want to interact with him because they understood how settlers sought to use photography as a form of dispossession.

The prevailing belief among Europeans at this time was that Indigenous people were inferior and destined to die out, so many photographers believed they needed to document Indigenous ways of life before they disappeared. The federal government was also involved in this undertaking through the Department of Indian Affairs. In the 1870s, the government commissioned images of traditional villages and Indigenous peoples, individually and in groups. Photographers such as Edward Dossetter (1843–1919) and Richard Maynard (1832–1907) travelled to communities on maritime inspection tours with Indian agents, and their work appeared in administrative reports to support the colonizers’ claims.

Following the takeover of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1870, the Canadian government grew concerned about conflict between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. To maintain social order, they formed a national police force in 1873 initially known as the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) and renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in 1920. In some countries, photography was introduced to policing in the mid-1850s, but in Canada it was not commonly used until the 1880s and 1890s, when portraits of the accused were collected in racks (called a “rogues’ gallery”) or were assembled in albums to track offenders. Commercial photographers were commissioned to photograph criminals; one such photographer was Hannah Maynard who worked for the Victoria police between 1897 and 1903. The photographs by Geraldine Moodie (1854–1945) of Indigenous subjects should also be considered within this framework because her photos accompanied her husband’s reports for the NWMP.

Government and social science applications of photography in the West were initially geared toward producing knowledge about the land and Indigenous peoples. However, with the push to develop the Prairies as an agricultural region in the 1880s, there was a growing recognition that photography could be helpful in promoting settlement, and railroads and developers sought to change the way the land was represented photographically.

The persuasive qualities of photography were recognized in the realms of commerce and industry as a powerful promotional tool for supporting the expansion of capitalism. Although images emphasizing vast expanses of unpopulated territory suited the needs of surveyors for the Dominion government, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and land companies wanted photographs showing a hospitable environment full of opportunity. For the most part, commercial photographers were hired for this work. William Notman’s son, William MacFarlane Notman (1826–1891), Alexander Henderson, and Oliver Buell (1844–1910) were among the photographers who made images along the CPR routes that the company used to encourage travel and settlement.

The CPR’s photographs were published in the company’s promotional material and hung in window displays and waiting rooms overseas, but they were also made widely available to publishers and used in encyclopedias and textbooks. Photographs emphasized well-established infrastructure, existing settlement, and symbols of progress such as cars, electricity, and machinery. These images tended to convey an idealized vision of the Prairies as an abundant agricultural region and nurtured an exaggerated narrative of success and plenty that deliberately misled would-be settlers.

The Ministry of Immigration and Colonization adopted the image of the West created by the CPR in their official publication, Canada West, and later, individual towns continued with this portrayal in their promotional literature. But the CPR’s promotional photographs looked much different from those made by community-based photographers. William S. Beal (1874–1968) was among a number of Black Americans who moved to the West in Canada for employment opportunities, in his case in a sawmill in western Manitoba. His photograph Portrait of Clarence Abrahamson in a field of marquis wheat, 1915, captures the fecundity of Prairie agriculture without romanticizing it.

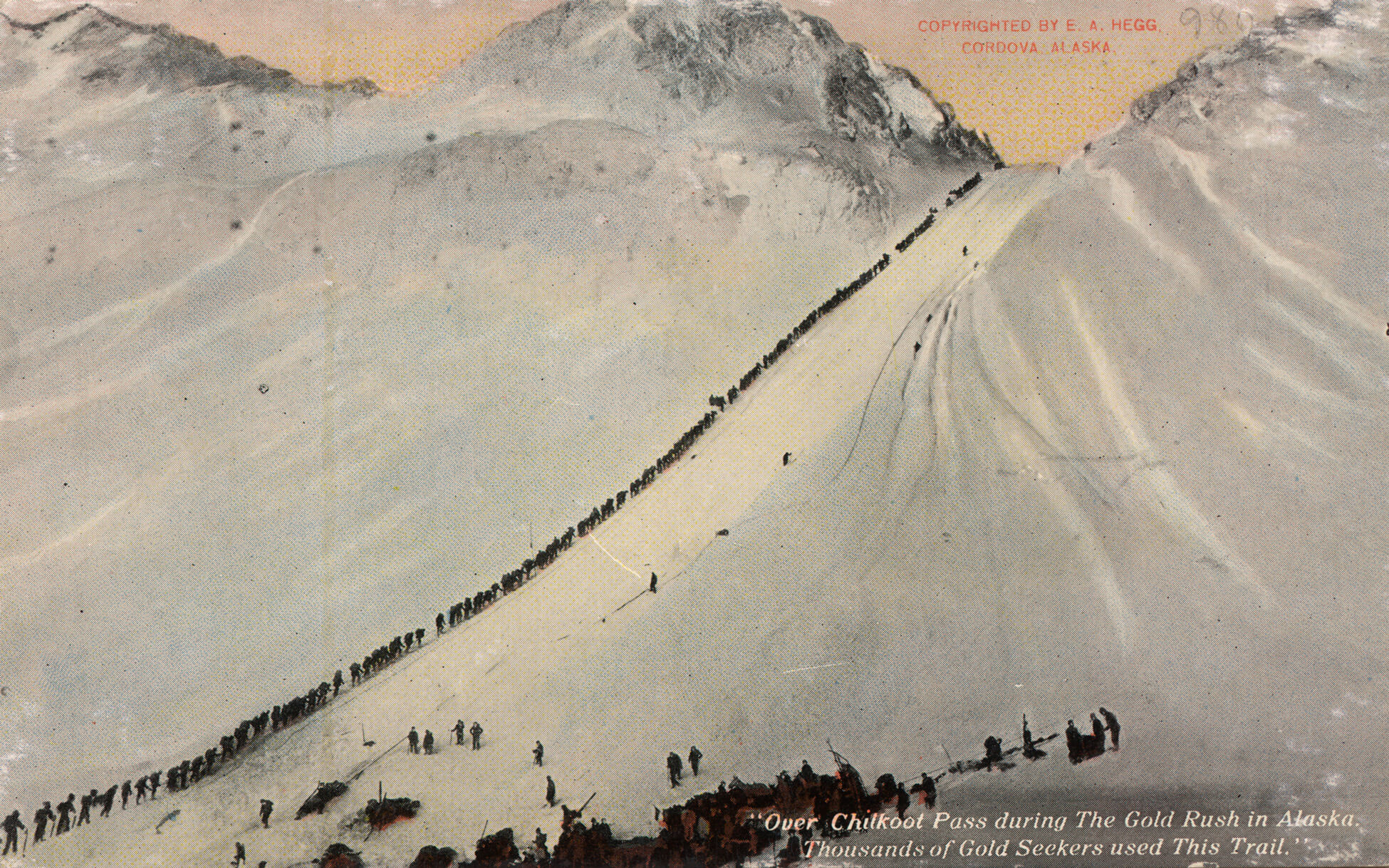

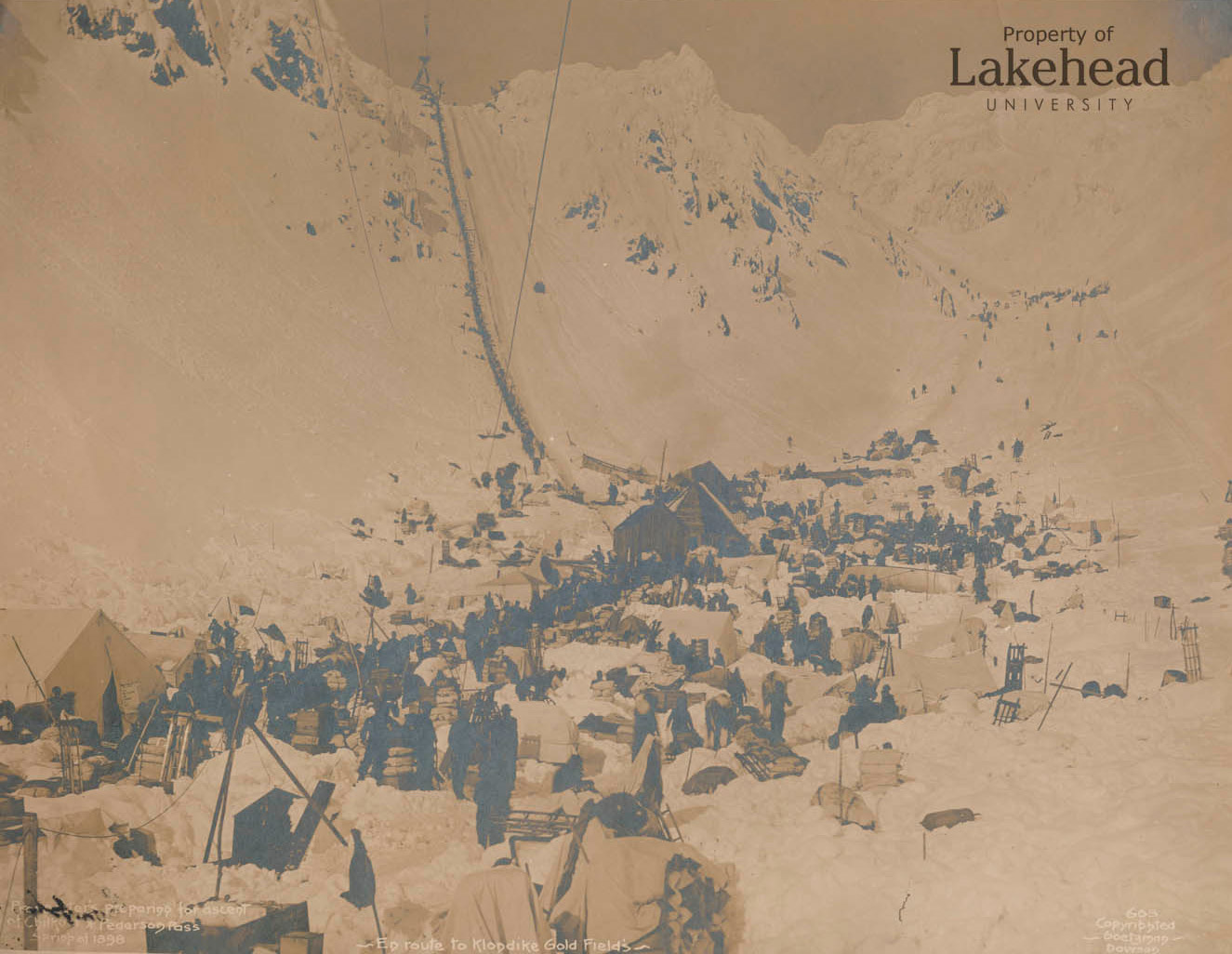

Events such as the Klondike Gold Rush (1896–99) led to a convergence of different practices of photography. In this instance, many geologists and surveyors adopted photography as a professional tool. Joseph Burr Tyrrell (1858–1957), who worked as a mining engineer in the Klondike, made photographs of ore deposits and mining procedures to illustrate his findings. But the Gold Rush also attracted professional and amateur photographers alike, and their images portray everyday life as well as scenes of the difficult mountain crossing from Alaska into the Klondike region of the Yukon.

The Chilkoot Trail was a Tlingit trade route that became the primary path for prospectors travelling to the goldfields of the Klondike until a railway was built in 1899. Scenes of prospectors ascending the summit, laden with supplies, was a favourite subject among professional photographers such as Eric A. Hegg (1867–1947), George Cantwell (1870–1948), Larss & Duclos Studio (1899–1904), and Henry and Mary Goetzman of Goetzman Studio (1898–1904). Many commercial photographers sold postcards, stereographs, and other popular formats to prospectors wanting to commemorate their Klondike adventures.

1890–1930s: The Growth of Photographic Art

At the turn of the century, Canadian art galleries and schools conformed to traditions from Europe, and painters such as Horatio Walker (1858–1938) and William Brymner (1855–1925) adapted French styles to depict rural Canadian landscapes. It was in this context that some photographers began exploring the artistic potential of photography, even as debates continued internationally about whether photography was an art or science.

Critics such as French poet Charles Baudelaire and art critic and historian Lady Elizabeth Eastlake had recognized photography’s potential as a new form of technology and communication in the 1850s, but they were reluctant to consider it an art form. Photography challenged established ideas about art because it was produced through machinery, rather than directly by an artist’s hand as with painting or sculpture. Nonetheless, some photographers explored its artistic potential by emulating certain aspects of painting, such as their choice of subject matter, composition, and allegorical message.

In the 1890s, Pictorialism emerged as a new international movement dedicated to an avant-garde movement of art photography. Leading figures of Pictorialism included Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) in the United States and Frederick H. Evans (1853–1943) in England. The Canadian scene was invigorated by artists in Canada, such as Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970) and Minna Keene (1861–1943), who were connected to these international networks. Keene was a fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in England and exhibited her work in their annual exhibitions before and after immigrating to Canada in 1913.

The Pictorialist movement was a response to the industrialization of the nineteenth century and a rejection of, and alternative to, the instrumental, functional uses of photography, both institutional and commercial. Pictorialists were motivated by an interest in the applied arts, specifically the idea, advocated by those involved in the Arts and Crafts movement, of harmony between the arts. Whereas designer William Morris (1834–1896) and other Arts and Crafts practitioners responded to industrial production by creating unique handcrafted furniture and decorative objects, the Pictorialists responded to mechanistic views of photography by creating an aura of artistry in their work.

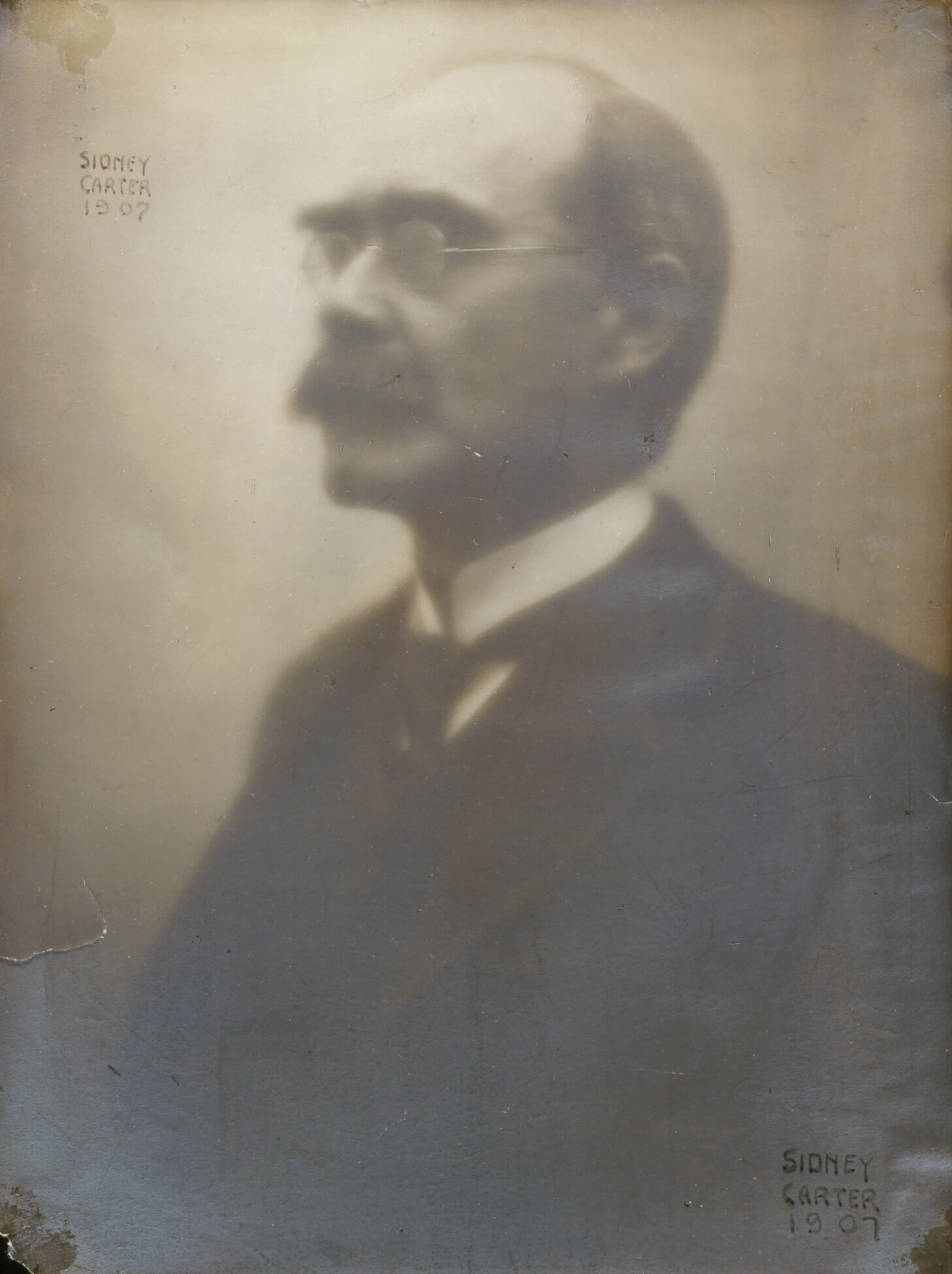

The Pictorialists turned to a range of subject matter, including portraits, landscapes, and still lifes, and emphasized individual expression as they experimented with photographic techniques and process, such as selective focus, atmospheric lighting, and gum bichromate and platinum printing to create painterly effects and establish mood. Connections to music and literature were explored through design principles, in particular harmony and unity, as well as in themes and subjects, as seen in a portrait of writer Rudyard Kipling, 1907, by Sidney Carter (1880–1956).

In Canada, the centres of Pictorialist activity were Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, and Vancouver, although the Toronto Camera Club was the main focus of activity at the turn of the century. One key figure was Carter, an early proponent of Pictorialism who exhibited in London, England, and was elected into the membership of the Photo-Secession group led by Alfred Stieglitz in New York. Carter was active in Toronto and, along with fellow member Arthur Goss (1881–1940), was involved in redecorating the club to create a style and atmosphere similar to Gallery 291, Stieglitz’s gallery in New York. This approach was a change from salon-style modes of display typical of earlier photography exhibitions because it emphasized the artistic qualities of individual works.

Goss helped found the Studio Club with other Pictorialists to exhibit in Canada and abroad with the belief that these exhibitions would help to build a network of art photographers across the country. These presentations of Pictorialist photography in the 1910s were important in developing a public dialogue about artistic photography as they invited responses in newspapers and magazines, including by art critic and fellow photographer Mortimer-Lamb.

Goss hoped that photographers would follow the example of the Group of Seven painters and define a uniquely Canadian style in art photography. At first glance, Goss’s artistic work appears different from the photographs he made in his job as the official photographer for the City of Toronto because of the soft lighting and diffuse backgrounds, such as in Child and Nurse, 1906. However, on closer evaluation, it seems that both bodies of work are born out of an interest in the changing conditions of modern life.

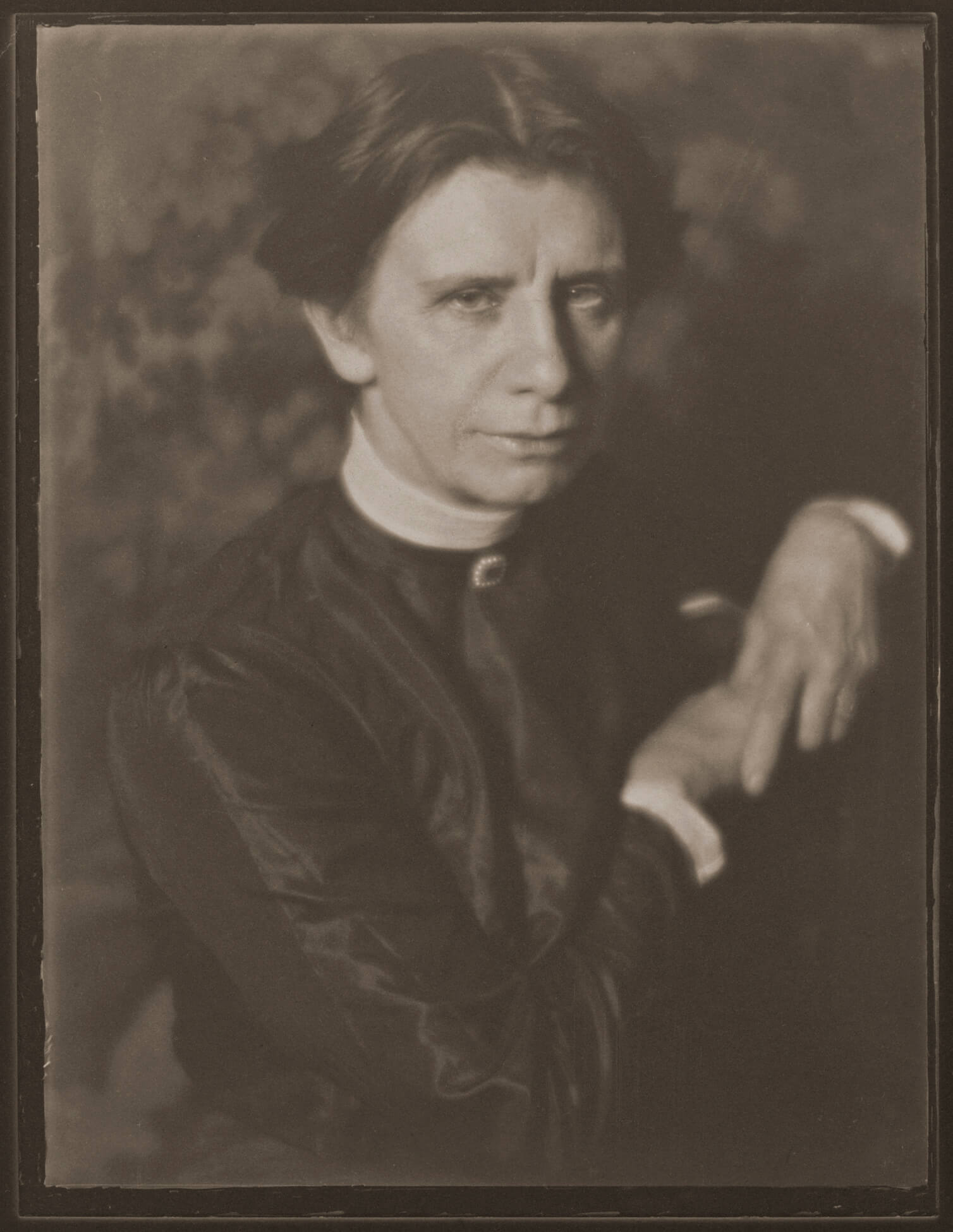

During the 1920s, photography was integrated into the developing structures of a Canadian art world. A select few art photographers played key roles in the arts generally and helped to build networks across the country. Mortimer-Lamb was one such figure. His commitment to the arts is evident from his concurrent involvement in painting, and this intersection is explored in portraits he made of friend and teacher Laura Muntz Lyall (1860–1930), a painter in Montreal.

On the West coast, John Vanderpant (1884–1939) was the founder of a major annual exhibition of photography in Vancouver that helped popularize photography as an art form. In 1928, with Mortimer-Lamb, Vanderpant founded one of the most influential commercial art galleries of the day. The Vanderpant Galleries showed modernist work ranging from Group of Seven paintings to photographs by Americans Imogen Cunningham (1883–1976) and Edward Weston (1886–1958). As he nurtured artists and built public interest in photographic art, Vanderpant earned international acclaim for his own photographs, such as Untitled, c.1930, which had transitioned from a Pictorialist to a modernist style.

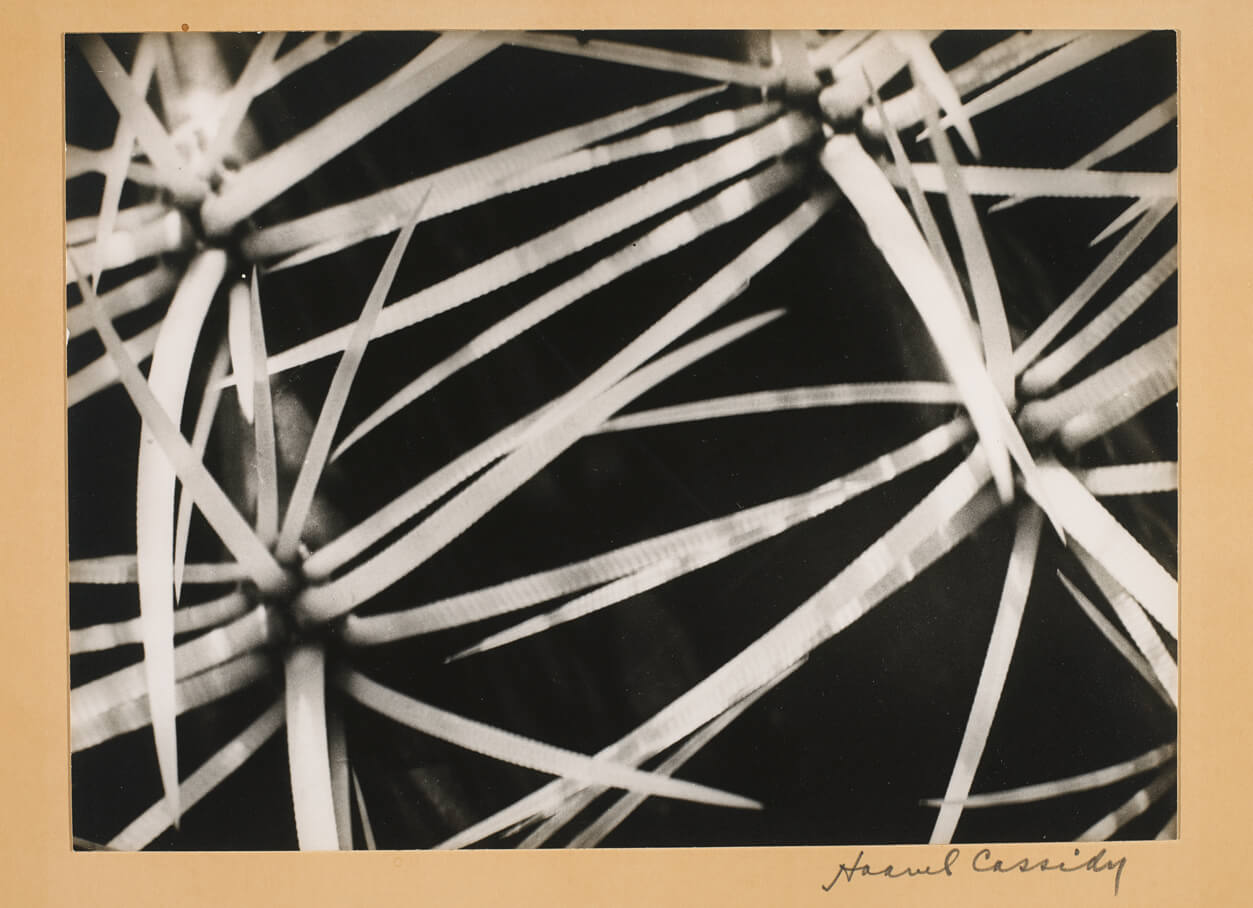

Although Pictorialism was concerned with validating photography as an art form, modernism focused on photography’s unique formal properties such as line, shape, pattern, and composition. For many practitioners, such as Eugene Haanel Cassidy (1903–1980), this meant exploring how photography could represent the world in unexpected and innovative ways. In the 1930s, Cassidy regularly turned his camera on plants, transforming them through lighting and radical cropping into exotic and often unrecognizable patterns, as in Welcome, c.1938. The formal language of modernism emphasized abstract form and design, although some photographers, including Vanderpant and Margaret Watkins (1884–1969), incorporated aspects of both Pictorialism and modernism in their work. This hybrid style combined geometric forms and dramatic contrast with soft focus and warm-toned papers.

Most Canadian photographers of this era who created photographs with an artistic intent were, like Cassidy and Watkins, also working in other realms. However, they drew on international artistic movements and helped to build the aesthetic infrastructure that would support the flourishing field of art photography in the postwar period.

1900–1940: Urbanization, Conflict, and the Rise of the Mass Media

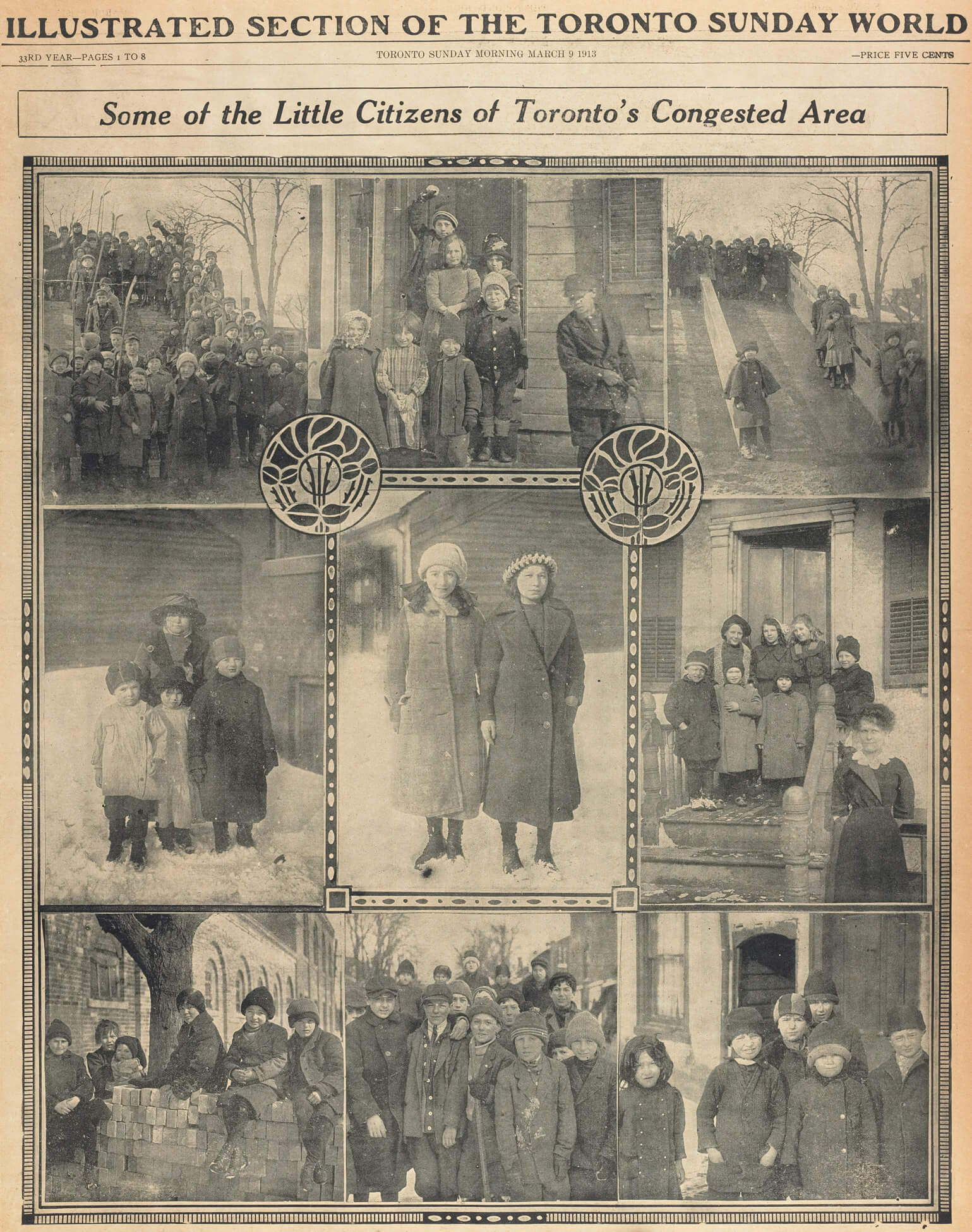

During the early twentieth century, photography became central to the way Canadians understood their place in the nation and the world. With the development of halftone printing, newspapers and magazines began publishing more photographs, often in separate illustrated sections, which were popular and helped newspapers boost circulation. This new exposure to photographs introduced readers to the world beyond their daily experience. Illustrated editions of newspapers such as Toronto World portrayed wilderness landscapes and hunting scenes that transported readers to remote areas of the country untouched by development, while also turning urban poverty into a spectacle for consumption. As photo historian Gisèle Freund observed, the mass dissemination of photography had a social impact because “as the reader’s outlook expanded the world began to shrink.”

With the public’s thirst for novelty and a rising demand for images, a new profession was born. Press photographers devised new reporting techniques, often going to great lengths to get the picture that would best tell a story. Their rationale was that the more adventurous the photographer, the more exciting the pictures. Photographers often climbed ladders to get a good view of a crowd, or flew in dirigible airships to capture aerial perspectives.

Hamilton-born Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870–1942) was known for her fearless pursuit of subjects and is shown here getting set to take midair photos at the 1904 World’s Fair. Beals was one of the first women to work in the field, and as press photographer for the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, her work was published in numerous papers, including the Buffalo Enquirer, the New York Herald, and the Tribune. In Winnipeg, Lewis Benjamin Foote (1873–1957) photographed crowds during the Winnipeg General Strike (1919), and in Toronto, the emotionally appealing photographs of William James (1866–1948) explored the changing nature of modern life. James photographed winter scenes of toboggan runs in High Park, and noteworthy events such as the first plane flight in the Toronto region (1910) were featured in local newspapers and magazines.

Photography continued to play an important role in attracting new immigrants to settle the Prairies in the 1910s. With the goal of building the country’s economy, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and his Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton, sought newcomers from previously untapped regions, especially central and eastern Europe. Under Sifton’s direction, William James Topley was hired to photograph new arrivals at the Hospital and Immigration Detention Centre in Quebec, and the Department of the Interior distributed Topley’s photographs as promotional material. As immigration surged, there was widespread discussion about how to “Canadianize” newcomers. These debates invariably intersected with anxiety about whether non-British immigrants would assimilate in Canada. There was also concern over conditions in the nation’s growing urban centres.

Photography figured prominently as a tool in diagnosing perceived urban problems such as unsanitary conditions and as a key means of influencing public opinion about certain ethnic groups. In Toronto, where many central and eastern Europeans settled, the official city photographer Arthur Goss made photographs as evidence of slum conditions, which the municipal government used to institute public health initiatives and social welfare reforms aimed at recent immigrants. Press coverage of immigration issues varied in viewpoint and tone depending on the publication, with a range of results. In the pages of tabloid newspapers, immigrants living in congested areas of the downtown were often pictured as a source of curiosity and an object of derision. In other publications, discussions focused on assimilating newcomers as a form of nation building and to preserve the liberal political order.

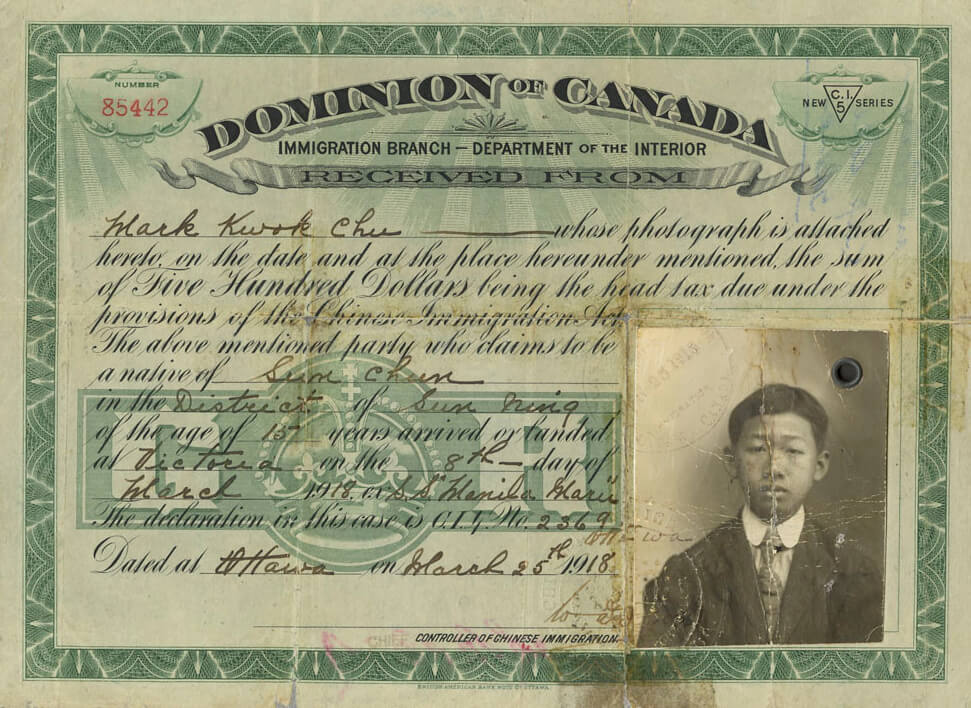

Although the federal government used photography to encourage immigration to Canada by some nationalities, the government also used it to regulate the entry of racialized subjects. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 required Chinese immigrants to submit identity photographs and pay what was called a head tax. This placed a significant and inequitable financial burden on Chinese immigrants to Canada. When the Act was repealed in 1923, it was replaced by the equally punitive and discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act. The Canadian government took escalating steps to dissuade and control Chinese immigration by increasing the tax tenfold between 1883 and 1903. In 1910, the government also added photographs to the identity certificates required of all Chinese immigrants, and this marked the first instance of the systematic use of photography in identification documents in Canada.

During the First World War (1914–18), the imagery of conflict was also managed by the government instead of the press. The Canadian War Records Office (CWRO), established in 1916 by Sir Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), oversaw the government’s program to document Canada’s war effort through painting, photography, and film. The program’s official photographers, Captain William Ivor Castle (1877–1947) and Lieutenant William Rider-Rider (1889–1979), were members of the British press who reported on Canada’s role in the war. Their images were used to generate public support for the war with photographs depicting common themes such as destroyed villages and ravaged landscapes. Photographing scenes after a battle or staging and combining multiple negatives into one print were sometimes considered reasonable alternatives to the danger of shooting photographs on the front lines.

These official war photographs were published in magazines and newspapers, but they also reached a wide audience through popular formats such as stereographs and postcards. Soldiers were prohibited from taking photographs due to security concerns; however, this regulation was not always followed, and some, such as J.A. Spencer, did compile albums of personal photographs, postcards, and newspaper clippings. Additionally, aerial photography was a new form of reconnaissance and it became important in military strategy.

-

William Ivor Castle, Misery Absolutely Destroyed by Germans Before Leaving, March 1917

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

-

J.A. Spencer, page 8 of Airships, Rigid and Non-Rigid, Howden, 1916–19

Album page: gelatin silver print

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

-

Princess Christian’s visit to the 2nd Exhibition of Canadian Pictures, Grafton Galleries, London, 1917

Photographer unknown

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Whereas photography figured in wartime operations in numerous ways, the prevailing functions were to shape public opinion and to create a historical record. Exhibitions of official war photographs, such as the Canadian War Records Office’s exhibit at Grafton Galleries in London, England, were extremely popular. Featuring framed prints that borrowed from the scale and drama of history paintings, these exhibitions presented a view of the war that was palatable for public consumption.

1939–1967: Global Conflict and the Cold War

By the Second World War (1939–45), state photography and the press gradually became more intertwined. Throughout the war, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), Still Photography Division (SPD), founded in 1941, advanced the war effort by publishing popular photo-stories that fostered national unity and boosted morale. Photographers such as George Hunter (1921–2013), Nicholas Morant (1910–1999), and Harry Rowed (1907–1987) focused on subjects such as civilian life, military operations, and industry. Some of the many photographs celebrating the manufacturing industry featured women’s contribution to the war effort through factory work. The SPD’s photographs reached a mass audience through general interest magazines in Canada and internationally.

The patriotic tone of the images even extends to images of Japanese Canadians interned under the War Measures Act in 1942. The nationalistic approach of the SPD is especially evident when contrasted with illicit photographs taken by people imprisoned in the Tashme internment camp and postwar portraits by Robert Minden (b.1941). These unofficial photographs engage in complex and varied ways with the suffering and loss associated with the dissolution of family and community.

Photography continued to serve as a tool of state propaganda during the Cold War, when Canada struggled to secure its sovereignty in the Arctic. In response to United States military presence in the region, in September 1951, the Canadian government sent a ship to re-open its northernmost RCMP outpost, in the High Arctic, about 1,200 kilometres (or 700 miles) north of the Arctic Circle. An SPD photographer accompanied the team and photographed the flag raising, dignitaries, a snow-clad mountain, and Inuit families gathered for the event. Although the photograph suggests that this was a natural location for Inuit inhabitants, Craig Harbour was abandoned as uninhabitable decades earlier. The Inuit families pictured were relocated to this settlement from Dundas Harbour, an RCMP post farther south that closed in order to re-open Craig Harbour. This would not be the first nor the last time the Canadian government coerced Inuit families to move and then photographed them for political purposes.

In contrast to the official images, in the following years, photographer Richard Harrington (1911–2005) published his own photographs of Inuit subjects. The photographs in Harrington’s book The Face of the Arctic, 1952, are accompanied by an account of his travels and interactions with Inuit, and for the most part he presented struggle as a fact of life in the North. However, his photographs of the Padleimiut depict people starving in desperate circumstances, and he criticized the Canadian government for its neglect.

Edward Steichen (1879–1973), director of the Photography Department at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, included three of Harrington’s Arctic photographs in the exhibition The Family of Man, 1955. Sponsored by the United States Information Agency, the exhibition was shown abroad as an instrument of Cold War cultural diplomacy. Five copies of the exhibition travelled to thirty-seven countries and approximately 9 million people saw the show between 1955 and 1962.

Described as “the most successful photography exhibition ever mounted,” The Family of Man included images by 273 photographers from sixty-eight countries and promoted American interests with the curatorial message of humanity as one family. The exhibition was shown at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1957, and it inspired Lorraine Monk, executive producer of the NFB’s SPD, to launch projects such as Call Them Canadians, which adapted the humanist message to a Canadian context.

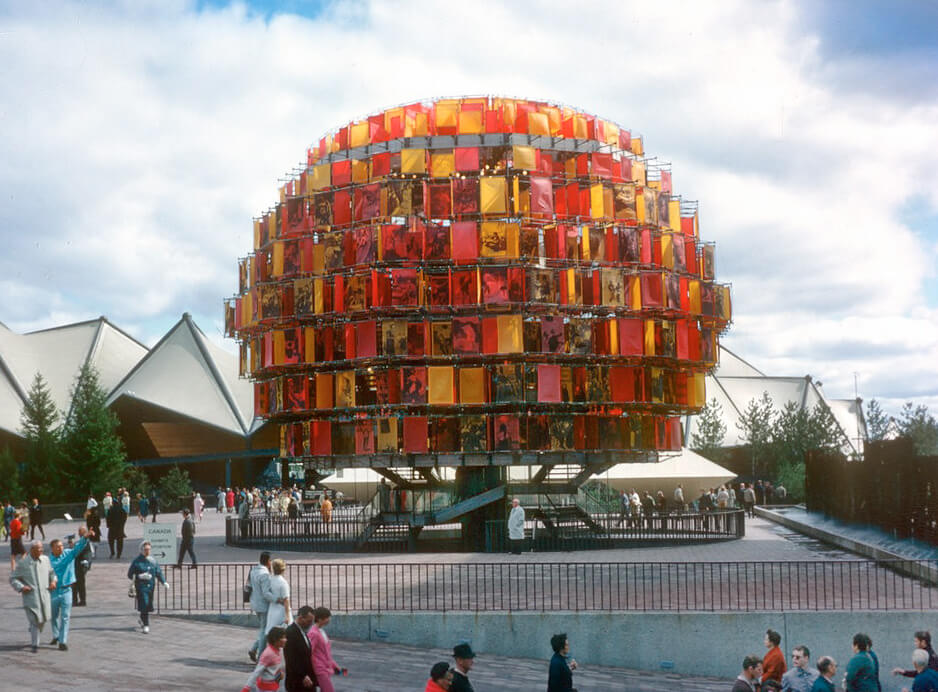

Photography also played a vital role in cultural diplomacy at Expo 67 in Montreal and was featured in brochures, on postcards, and on many other souvenirs, including a book of photographs of Canada by Roloff Beny (1924–1984) called To Everything There Is a Season (1967), which served as an official government gift to visiting heads of state. In addition, photography was integrated into the architecture of the Expo 67 site, with structures like the People Tree, 1967, an installation at the entrance of the Canadian Pavilion that was another of Monk’s projects. The People Tree was a 21-metre (70-foot) construction surrounding a spiral staircase that took the form of a maple tree. The “tree” was adorned with seven hundred photographs of Canadians printed on orange and red nylon sheets. Staff at the SPD selected photographs, such as a 1965 image of a woman trying on a hat in a millinery store by Pierre Gaudard (1927–2010), for the display with the aim of creating a “Canadian Family of Man.”

Similar to its American counterpart, the People Tree installation was designed to bring people together, but the photographic display also aligned with the Canadian government’s policy of multiculturalism to present pluralism as a defining feature of national identity. Adapting Steichen’s message of the essential oneness of humanity, People Tree was an attempt to create a positive image of Canada for a national and an international audience during the country’s centenary celebration.

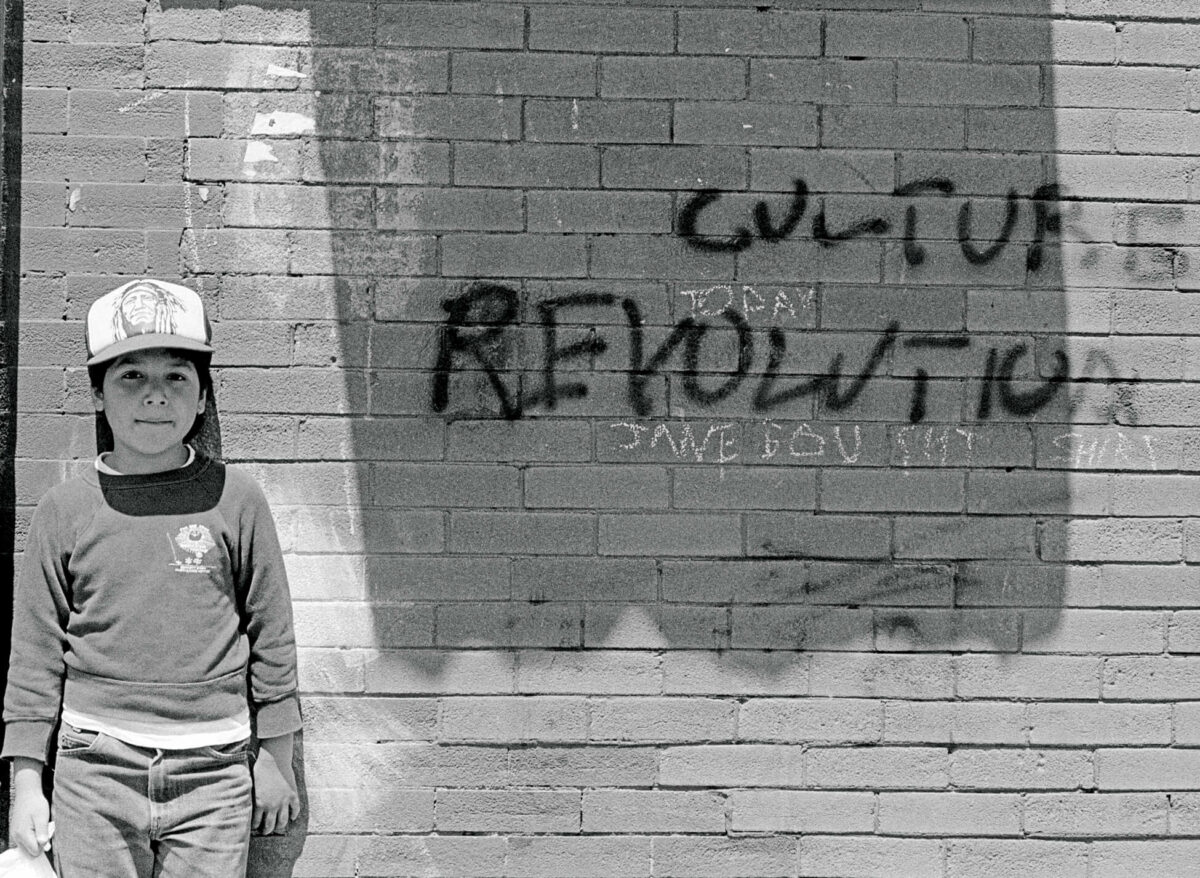

In the 1960s, a range of social movements developed in response to growing awareness of various forms of inequality. Campaigns for women’s rights, Indigenous rights, and rights for the LGBTQ2S+ community resulted in changes such as universal suffrage and the decriminalization of homosexuality. Photography was an important aspect of these social movements, as it was a way to record and publicize social protests and also provided recognition. For marginalized groups, photographic self-representation was at once an affirmation and a means of securing political representation.

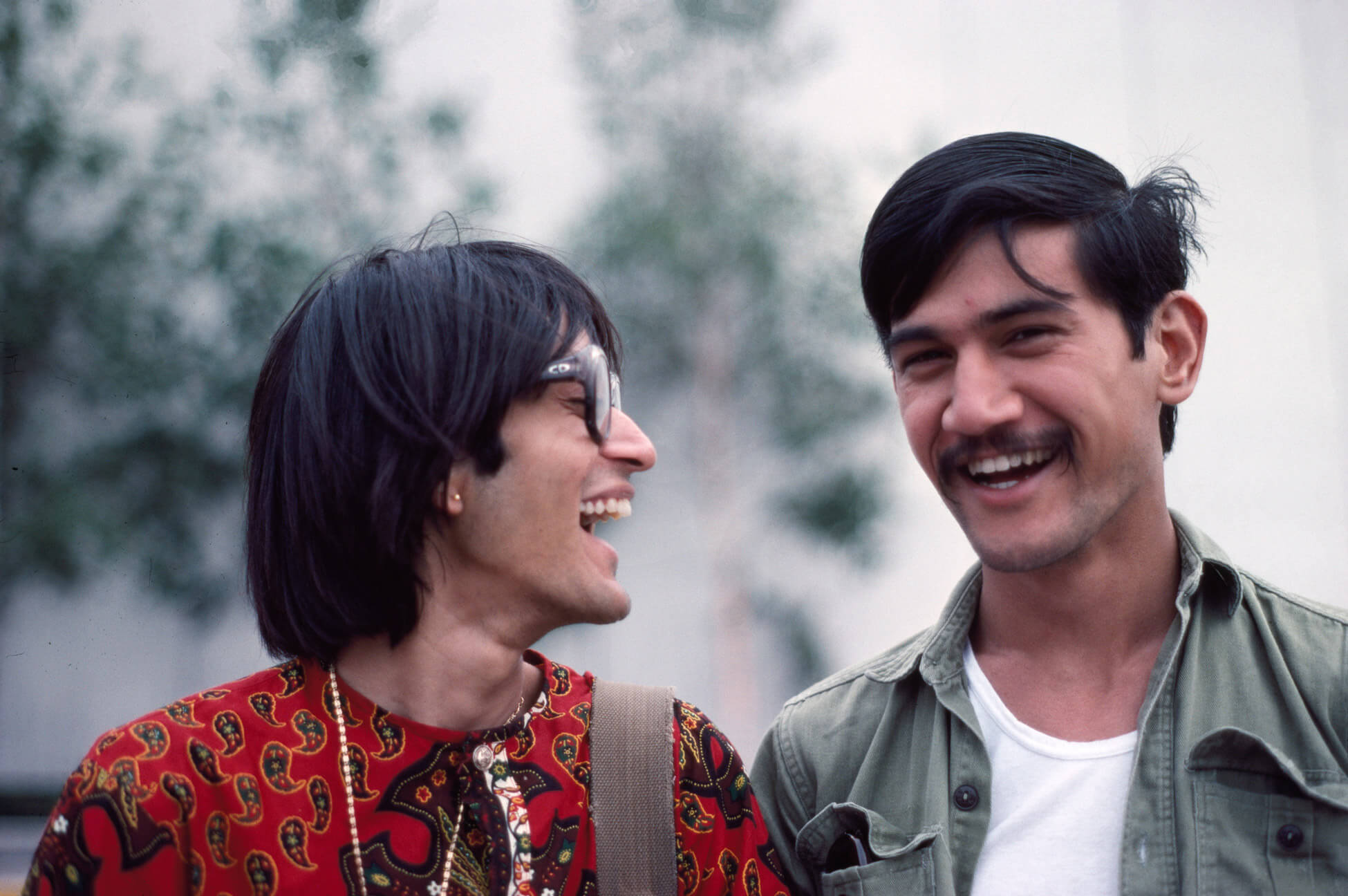

Journalist Gerald Hannon (1944–2022) and others embraced photography in their quest to document gay liberation parades, actions such as kiss-ins, court cases, and conflicts with the police. But while press photographs contributed to the public visibility of queer communities, personal snapshots were a way for individuals to explore gender identity. After Sunil Gupta (b.1953) immigrated to Montreal in 1969, he began to photograph his friends and lovers as part of the process of coming out. These images convey his experiences of building family and community during the gay liberation movement. The photographs in the Casa Susanna collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto depict visitors at a resort for cross-dressers in upstate New York and are a prime example of the role photography played in the formation of queer and trans communities. Later in the 1970s and 1980s, the artist collective General Idea (active 1969–1994) appropriated materials and strategies from the mass media in projects such as FILE Megazine, which references the popular American picture magazine, LIFE. The group challenged artistic and social conventions with their queer sensibility. Meanwhile, Toronto-based artist Nina Levitt (b.1955) made work about lesbian sexuality, and a Vancouver artist collective, Kiss & Tell, provoked debates about lesbian sexuality and desire with a controversial exhibition.

In the 1970s, photographers developed new approaches to documentary and explored changing social relationships. Immersing themselves in new environments and cultures, photographers expressed subjective experience and political perspectives in their individual and collective projects. To reach new audiences, photographers including Alvin Comiter (b.1948) and Clara Gutsche (b.1949) published photo books and exhibited their work in art galleries.

In Quebec, the Quiet Revolution brought about a series of reforms aimed at secularizing government, thereby transforming the province’s social, economic, political, and artistic landscape. Photography in Quebec ran parallel to the social unrest as photographers became involved in movements for political change. The socially engaged photography collective Groupe d’action photographique (GAP), which included Claire Beaugrand-Champagne (b.1948), Michel Campeau (b.1948), Gabor Szilasi (b.1928), and others, documented the decline of rural life in Quebec during a period of cultural renewal, urbanization, and modernization. As the federal government recognized the social value of immigration and adopted a policy of multiculturalism, Michael Semak (1934–2020) photographed immigrant communities including Italians in Toronto and Ukrainians on the Prairies.

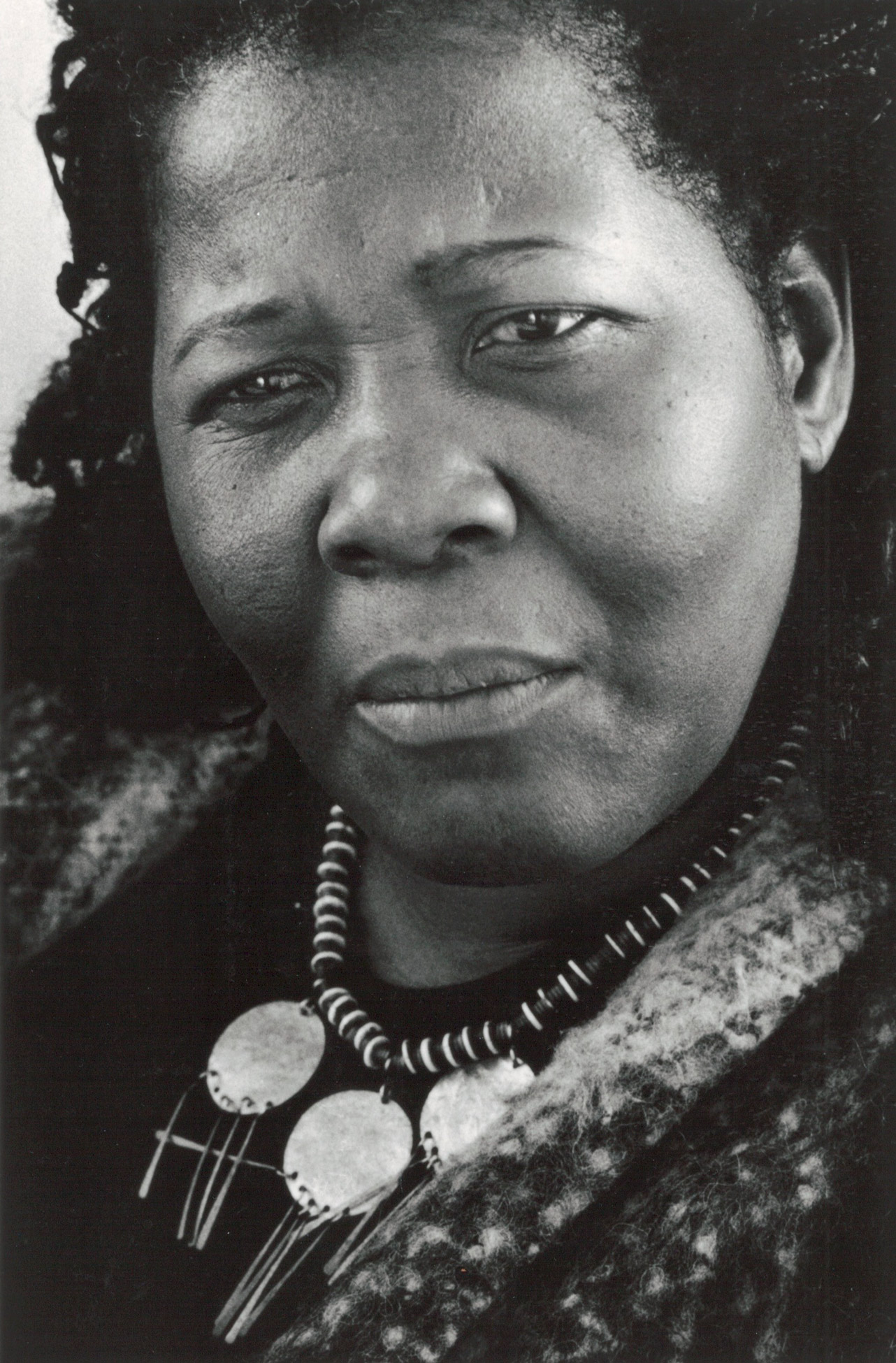

Also at this time, public inquiries, in particular the Royal Commission on the Status of Women (1967–70), along with related legal and policy changes, improved opportunities for women in Canada. Faces of Feminism, 1992, by Pamela Harris (b.1940) is an important testament to the work of women from different ethnic backgrounds, classes, sexual orientations, and professions across urban and rural Canada. The project that began in 1981, and resulted in an exhibition and book, is a collection of portraits paired with text written by the sitters to celebrate women who have struggled to transform patriarchy.

The changing social and political climate was both shaped by and had an impact on the art world and the place of photography within it. Artists began to engage with social and political issues, frequently using new media and innovative techniques, including photography. In the 1970s, Suzy Lake (b.1947) turned to photography as she explored gender as a social construct. Using herself as subject, she engaged with questions of perception and experimented with femininity as performance. In Miss Chatelaine, 1973, Lake applies makeup and poses in a variety of hairstyles as a commentary on beauty standards and the constraints of gender conventions. In the mid-1980s, First Nations artist Jeff Thomas (b.1956) began challenging European stereotypes of Indigeneity with a series of portraits of his son Bear pictured in urban settings.

Also important in this period are early photographic investigations of land use, pollution, and the human impact on the environment. In artwork from 1985 depicting open pit mines, railcuts, and tailing ponds, Edward Burtynsky (b.1955) developed his signature style of highly detailed, aesthetically engaging images depicting the damaging effects of industrial culture.

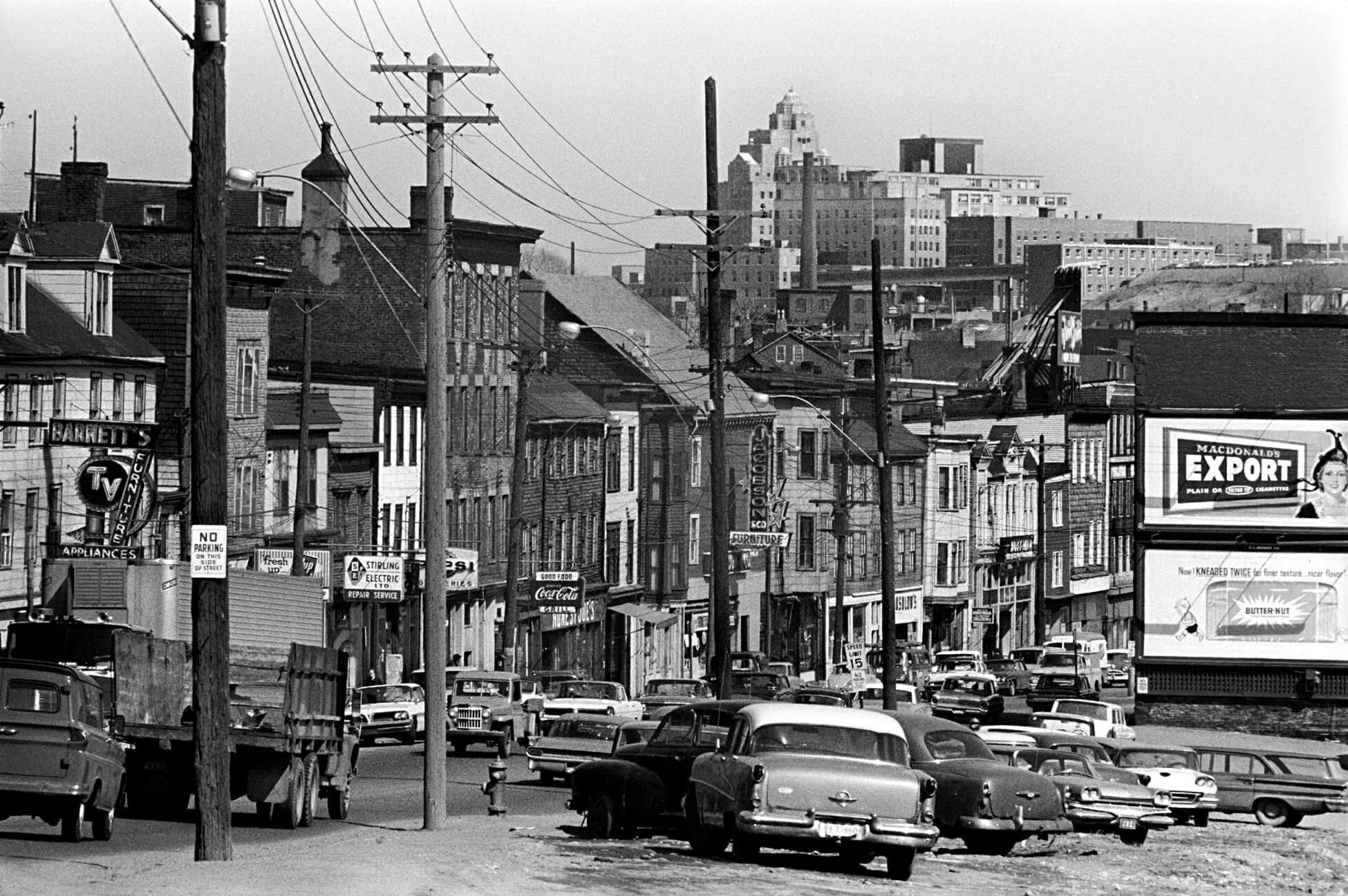

The 1960s through the 1980s was a period of growth in the arts sector, with the formation of artist-run centres, the construction of regional galleries, and new opportunities for funding from the Canada Council for the Arts. At the same time, the status of photography in the art world changed as major galleries in Canada began to collect and exhibit photographs as contemporary art. Photographers embraced new forms of documentary photography as a means of conveying subjective experience and as a way to explore social issues. Instead of publishing photographs in magazine photo-essays, the new documentary movement circulated photography as an art form. For instance, the socially engaged investigation of poverty and urban development in Saint John, New Brunswick (1966) by Ian MacEachern (b.1942) did not make the news but was published in artscanada.

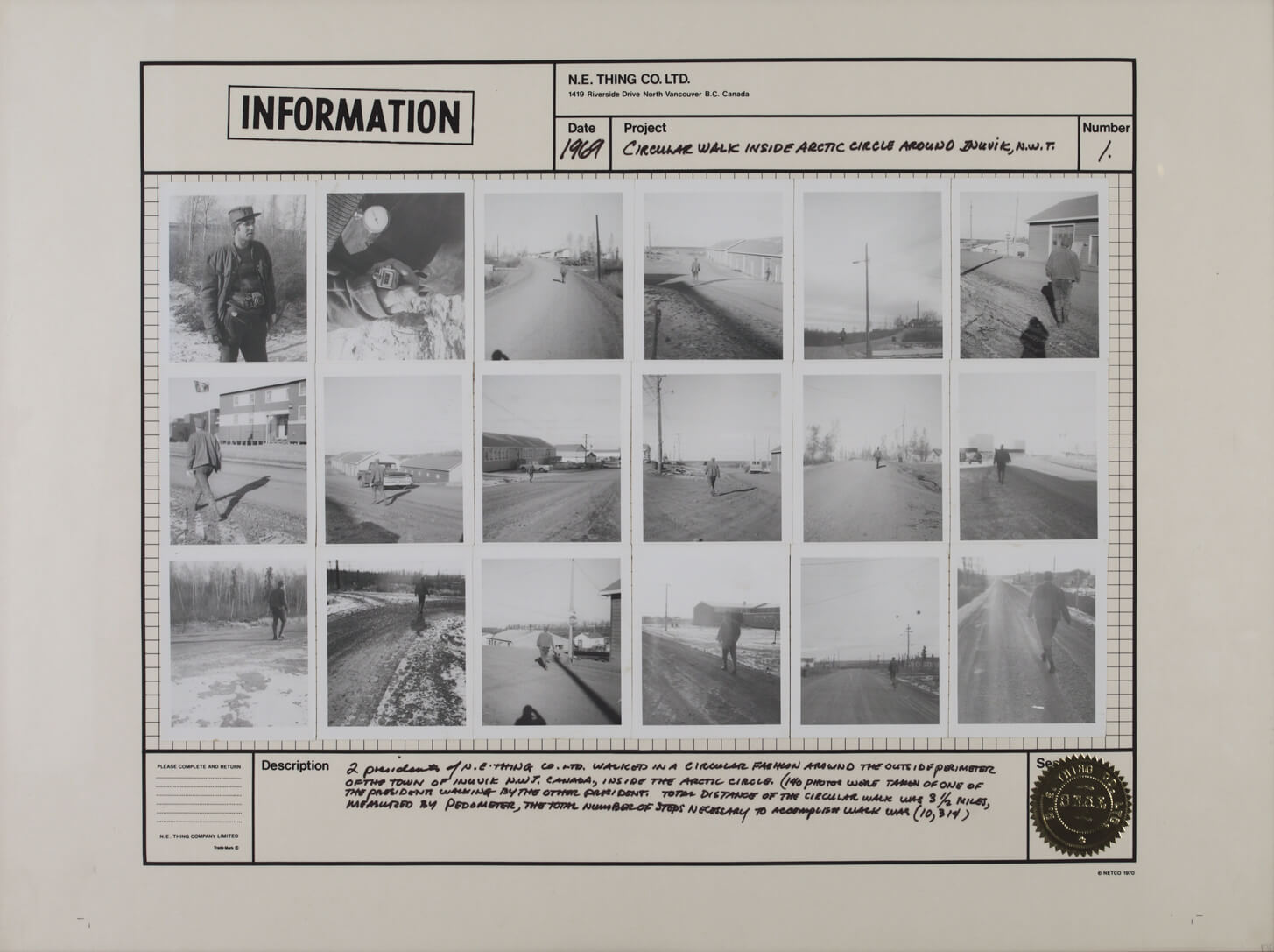

On the other hand, conceptual artists such as Serge Tousignant (b.1942), Bill Vazan (b.1933), and others embraced photography as they shifted away from the art object toward the expression of an idea. For the art collective N.E. Thing Co. (active 1966–78), the photograph was not a record of a moment in time but the product of careful planning, as well as a means to deconstruct colonial power relations and critique romantic ideals about landscape.

Vancouver was home to a burgeoning alternative art community in the 1960s, and it was within this context that the so-called Vancouver School of photo-conceptual art was founded. This informal circle of artists, which included Roy Arden (b.1957), Stan Douglas (b.1960), Ken Lum (b.1956), Jeff Wall (b.1946), Ian Wallace (b.1943), and others, connected over their methodology rather than a particular aesthetic. Influenced by post-structural theory, they developed a range of strategies, such as appropriation, juxtaposition, and cinematic tableau, to explore how representation generates meaning.

By 1989, photography encompassed a diverse range of image-making practices, from the commercial and the artistic to the vernacular. The next chapter of this history, from 1990 to the present, is beyond the scope of this book, as new technology, including the shift from analog to digital and the advent of the internet and social media, has completely transformed the way people communicate. In addition, intersections between photography and contemporary art have become more diverse and complex.

Over its first 150 years, as photography has permeated all aspects of life, it has inspired national myths, shaped interactions between people, and influenced patterns of migration and settlement. Photography has also created opportunities for shared experience and poetic expression. In Canada, photography has taken many forms and plays multiple roles, but at its richest and most fascinating, photography is a site of encounter and means of shaping our ideas about the world.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements