Sam Tata (1911, Shanghai, China–2005, Sooke, British Columbia)

Angels, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, Montreal, Quebec, 1962

Gelatin silver print, 29.2 x 36.8 cm; image: 22.6 x 34.1 cm

CMCP Collection, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Surrounded by quizzical children and their oblivious parents, the angels in the foreground of Angels, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, Montreal, Quebec by Sam Tata (1911–2005) could hardly be less celestial. Taken in the early days of the Quiet Revolution, what Tata captured was a “decisive moment,” a phrase his mentor, the legendary French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908–2004), applied to a fleeting image that fully represents a complex event.

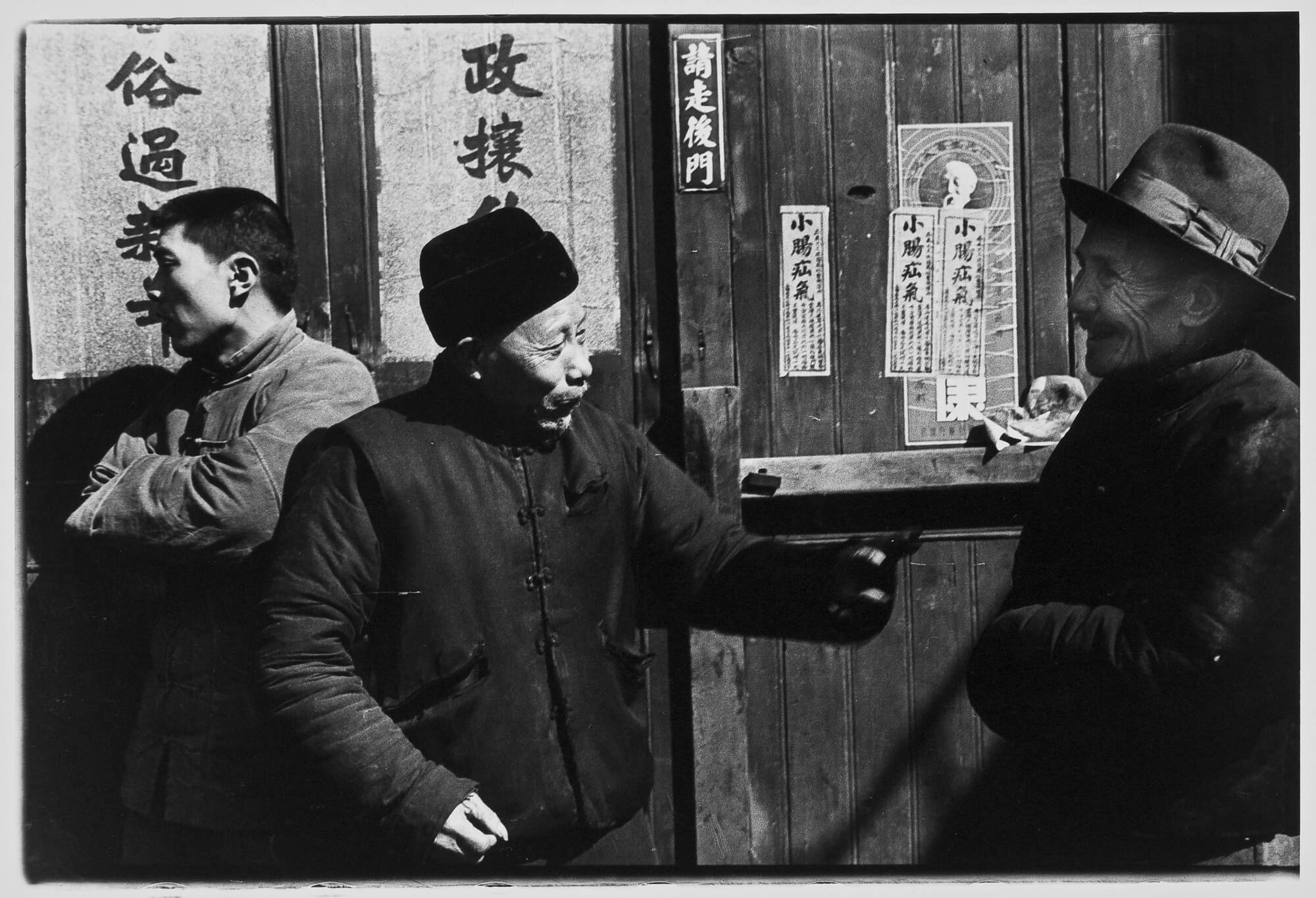

Tata was born in Shanghai to Parsi parents who migrated from India to China before his birth. After attending university in Hong Kong, he became interested in photography in his mid-thirties. He joined a camera club, bought a Leica, and began to photograph the streets of the cosmopolitan city—Street Conversation, Shanghai, 1938, is an example of this body of work. When the Japanese occupation of China made public photography difficult, Tata turned to portraiture. His first exhibition in 1946 paired his Pictorialist portraits with landscapes by famed photographer Lang Jingshan (1892–1995). From 1946 to 1948, Tata lived and worked in India, where he met Cartier-Bresson, who had been sent by LIFE magazine to document India’s independence in 1947—he became Tata’s mentor, colleague, and lifelong friend.

Tata returned to Shanghai in 1949 as the Communist takeover was in full swing, and he captured the events in images such as Cultural Parade with Posters of Mao Tse-Tung and Chu Te, July 4, 1949. He and his extended family fled to Hong Kong in 1952, and by 1956 Tata and his wife and daughter had left for Montreal. He smuggled his images of the revolution out of China through a diplomat, but customs censors seized many of his photographs of old Shanghai. This loss of early work was compounded when Tata later renounced his Pictorialist phase and destroyed many of his photographs.

In Canada, Tata worked steadily as a freelancer for the National Film Board and national and international magazines, where he often chafed at the need for his photographs to be tied to text and stories rather than allowing them to speak for themselves. He exhibited and later published his work from China and India and eventually found subjects for his street-focused photography in the various cultural and religious festivals in Quebec.

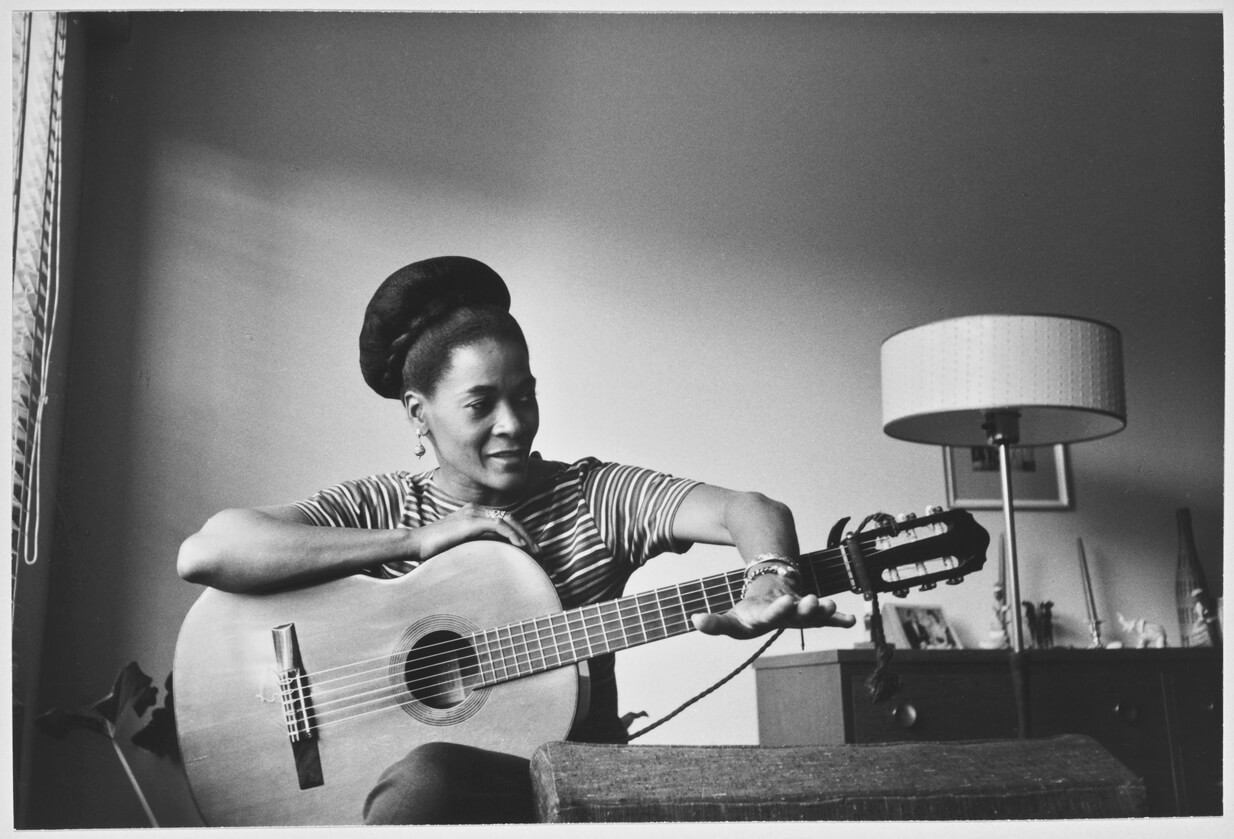

Tata is also known for his portraits of writers, artists, and performers, each one sensitively set in the subject’s work space and posed with evidence of their profession, as can be seen in Lucie Guannel, Singer, Montreal, Quebec, 1961. Many of these were commissioned by Time magazine and were later compiled as A Certain Identity: 50 Portraits (1983). Tata served as a mentor and friend to several photographers in Montreal, some of whom appear in his portraits, just as he appears often in the work of Nina Raginsky (b.1941) and Gabor Szilasi (b.1928).

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements