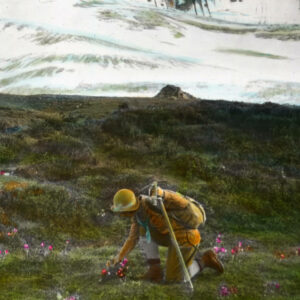

Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870, Hamilton, Ontario–1942, New York)

Self-portrait, World’s Fair St. Louis, 1904

Gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 11.4 cm

New York Historical Society Museum and Library

With Self-portrait, World’s Fair St. Louis, Jessie Tarbox Beals (1870–1942) reveals how she charmed and elbowed her way into places to capture candid images of major public events—from her spot at the top of the ladder, she is poised to photograph visiting dignitaries. Her path to this position was unusual: born in Hamilton, she trained as a schoolteacher before moving to the United States at age seventeen. Not surprisingly, she first developed an interest in photography as a tool of education, but after meeting American photographers Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864–1952) and Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934), she recognized the professional possibilities of the medium and soon became an intrepid reporter. By 1902, she had been hired by two Buffalo newspapers, likely making her the first woman in North America to work as a photojournalist, with her husband serving as her assistant and printer.

Over the next few years, her work was published in a wide variety of newspapers and magazines to great acclaim. In 1904, Beals was sent to cover the World’s Fair in St. Louis. She was particularly drawn to the dehumanizing living exhibits of “exotic” peoples brought to be presented at the fair. Patagonians from South America and Pygmy peoples from Congo were set up in exhibits designed to emphasize American’s progress, as well as to provide so-called entertainment for visitors. Beals sold several of her ethnographic portraits to newspapers and bundled them as sets and albums for purchase. Her curiosity about the world was an important part of her success, but, as photo historian Laura Wexler has argued, it is essential to recognize that her work was a form of violence against racial others.

After the World’s Fair, Beals’s staff positions ended, and she turned to freelance work. But as the field of photojournalism became more professionalized, she found it harder to compete for work as a woman, and she set up her own studio in bohemian Greenwich Village, New York. Although Beals never returned to live in Canada, she participated in at least one Toronto Camera Club International Photo Exhibition, in 1921. She died destitute, but most of her negatives were rescued by photographer Alexander Alland (1902–1989), who bought them from her heirs and donated them to the New-York Historical Society.

About the Authors

About the Authors

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements