Cape Dorset artist Oviloo Tunnillie was five years old when she got tuberculosis and was flown south for treatment — twice ripped from her family.

Darlene Coward Wight also had tuberculosis at the age of five and spent a year at a hospital.

Later, the Inuk stone carver would create pieces about this tragedy, among other evocative pieces — and Wight would write about them.

“She had it way worse than I did. She was taken from her family,” said Wight, author of a Art Canada Institute’s new ebook Oviloo Tunnillie: Life & Work.

Wight — also the curator of Inuit art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery where several of Tunnillie’s stone carvings are housed — said she discovered personal connections like this while researching the late carver’s life.

“This really resonated with me in a big way.”

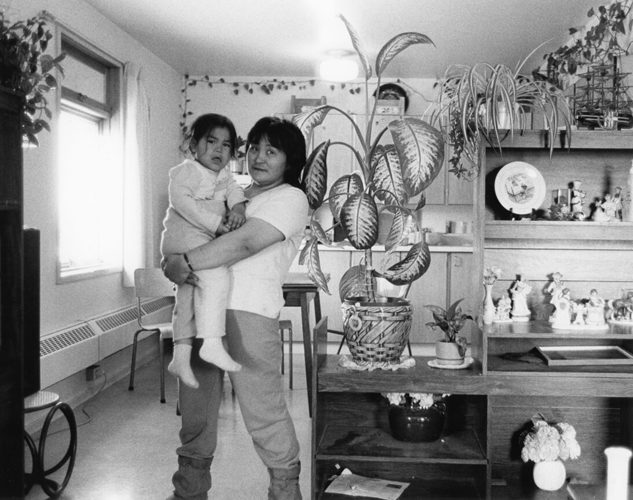

Tunnillie was born in 1949 and raised in camps on southern Baffin Island, before settling in Cape Dorset in 1972. Tunnillie’s father Toonoo was a carver, a common trade for men.

“She just adored her father,” said Wight.

Instead of learning to sew like most little girls did at the time, Tunnillie was “way more interested in watching her father carve,” said Wight.

She made her first carving as a teen, which was a turning point in her life. Tunnillie later became one of very few women Inuit stone carvers to get national and international recognition.

Serpentinite (Kangiqsuqutaq/Korok Inlet), 25.7 x 15.6 x 9.5 cm, signed with syllabics and dated 2001, collection of John and Joyce Price

She was diagnosed with cancer in 2012 and died in June 2014.

“She worked all the time,” said Wight. “She defied stereotypes and went ahead and carved even after she had cancer.”

Finding Tunnillie’s pieces like detective work

The day after Tunnillie’s death, a gallery director in Vancouver asked Wight to do a retrospective exhibition on the artist’s sculptures — and so began Wight’s search for Tunnillie’s finest pieces dispersed across North America in public and private collections.

It was like detective work, Wight said.

“[The curator] was very interested in this because usually carvers are not women, especially in Cape Dorset,” said Wight.

And that’s how Sara Angel found out about Wight’s expertise on Tunnillie.

While she was completing her PhD in art history, Angel said she realized there was an absence of resources on Canadian artists written by experts so she founded the Art Canada Institute, which publishes free books.

Angel approached Wight and asked her to author the book and Wight began to pen it last year.

‘Fearless’ in difficult subjects

Tunnillie also did a carving about the Inuit dog slaughter in the 60s and 70s.

“She was fearless in depicting subjects that were difficult,” said Wight.

Wight said Tunnillie’s work differed from what carvers typically did like mythological creatures, wildlife and hunting scenes.

Serpentinite (Tatsiituq), 35 x 12.5 x 11.3 cm, signed with syllabics, Winnipeg Art Gallery

“She was able to put emotion into her stone carvings, they are so emotive and evocative,” said Wight. “Her works were just so unusual.”

There are grieving women, women who have been possibly abused, even nude female figures.

“This was groundbreaking,” said Wight. “She showed the female nude was OK to do.”

One of Wight’s personal favourites is the grieving woman, from 1997. A woman stands with a hand to her brow, her body bent over in grief.

Tunnillie carved it right after her daughter died by suicide, said Wight.

Wight said Tunnillie’s legacy has influenced generations of artists from Cape Dorset, from graphic artists like Annie Pootoogook, to male carvers.

People can see Tunnillie’s work across North America like at the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa, Winnipeg Art Gallery, Feheley Fine Arts in Toronto, among others.

Oviloo Tunnillie: Life & Work can either be viewed online or downloaded as a PDF.

Read the article as originally published here.