Artists in Quebec City have always played a significant role as community builders. Their creative power has brought together individuals from other sectors of society (political, religious, secular) whose innovative and persuasive visions have also contributed to making Quebec City the cultural epicentre it is today. This selection of community-building figures invites us to reflect on the early days of the colony and trace a path to the present. Our story begins with a builder inspired by her Catholic faith, a creator in words and embroidery who helped lay the city’s cultural foundations. The story concludes centuries later, with a Wendat builder who has succeeded in rewilding today’s art scene.

Marie de l’Incarnation (1599–1672)

The religious fervour of Marie de l’Incarnation, née Marie Guyart, is deeply rooted in her complex personality and strong sense of action. She was not only the superior of a religious community established during the early days of New France but also the author of nearly ten thousand letters and three autobiographical works. These writings form a fascinating narrative of early colonial history, from her arrival in 1639 until her death in 1672. Many specialists from various fields continue to draw inspiration from them and from the life of this community builder who played such a pivotal role in fostering culture and the arts in Quebec City.

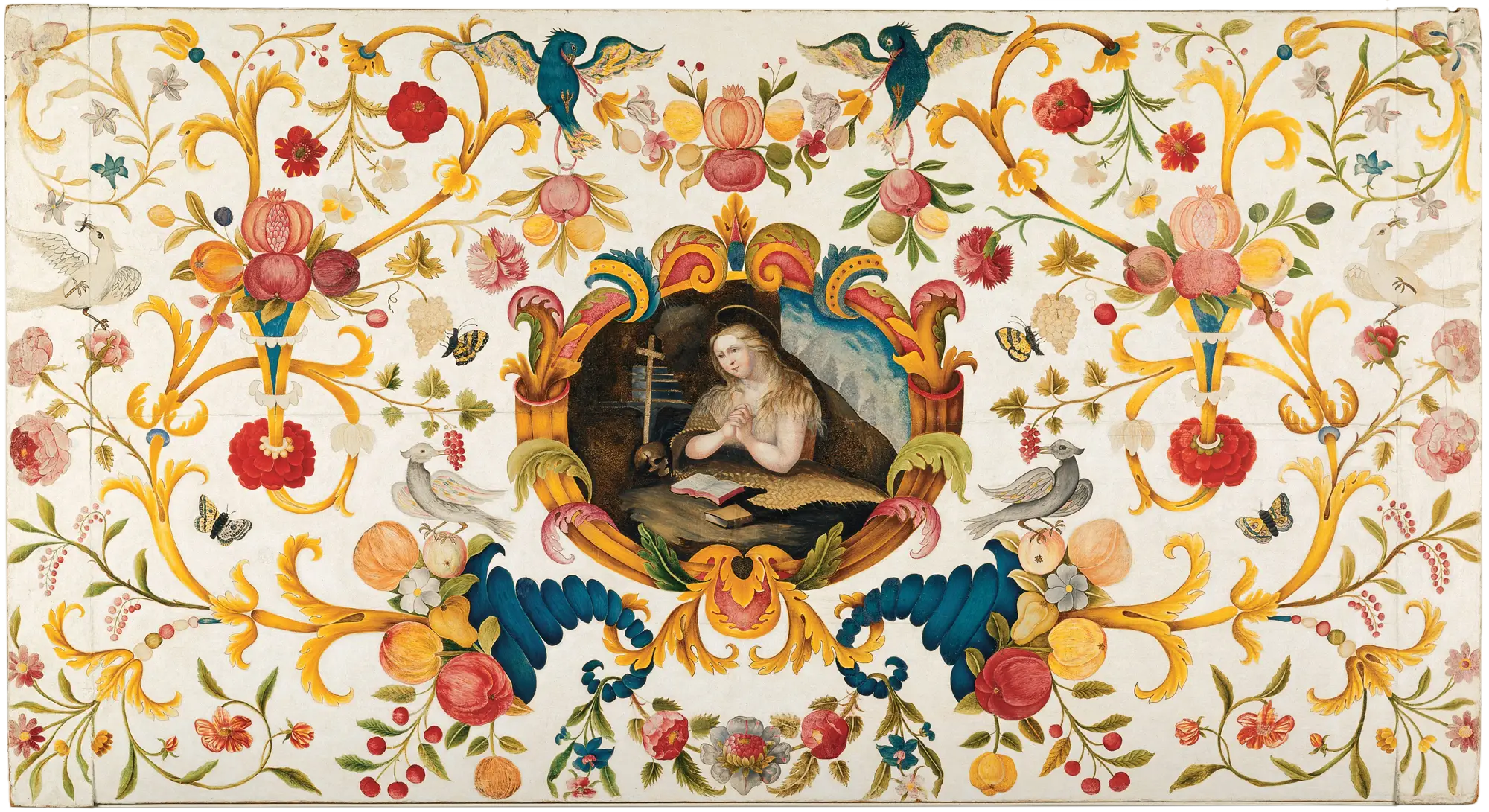

A woman of her time, Marie de l’Incarnation was skilled in the art of embroidery, which she taught to Indigenous and French schoolgirls newly settled in her cloistered monastery in the city. She is credited with creating the Parement d’autel dit de l’éducation de la Vierge (Altar Frontal Known as The Education of The Virgin), second half of the seventeenth century, which attests to the high quality of her embroidery work.

Widowed at nineteen, the Frenchwoman, then known as Marie Guyart, entrusted her son’s upbringing to her sister and joined the Ursulines of Tours, her hometown, in 1631. Eight years later, she embarked for New France. She founded the first educational institution offering instruction for young girls in a wooden monastery in Quebec City’s Lower Town, which at the time had a population of barely 240 and looked like a trading post. Gifted with a keen business sense, Marie de l’Incarnation managed the everyday affairs of the school and the girls’ seminary. In 1642, she designed and oversaw the construction of the Ursulines’ new stone monastery and chapel in the Upper Town.

A woman of letters, Marie de l’Incarnation was a prolific and skilled writer in her native French, but she also devoted herself to learning Indigenous languages, first Algonquian and later Iroquoian, which she learned with the help of Jesuits and subsequently taught to her fellow nuns. She went on to compile dictionaries, including a catechism in Wendat and later in Algonquin. Her artistic talents were expressed through embroidery and needlework, and her pieces were characterized by a refinement typical of French artistry. This work was carried on by her successors—notably Marie Lemaire des Anges (1641–1717), the likely creator of the Parement d’autel dit de la Nativité (Altar Frontal Known as The Nativity), second half of the seventeenth century.

Marie de l’Incarnation played a central role in the spiritual life of Quebec City’s small community, nurturing it by providing sacred ornaments, liturgical garments, and furnishings to the Ursuline Chapel for religious celebrations. These items were acquired through her connections with religious communities and noble patrons in Paris. During the liturgical celebrations of Quebec City’s religious calendar, the precious treasure of sacred ornaments was displayed to the faithful as a reflection of the Ursulines’ artistic and spiritual dedication.

The nuns also practised the art of gilding, which involves applying a thin layer of gold leaf to sculptures or wooden ornamentations, as well as decorative painting, primarily on sculptures. In the seventeenth century, when the creation of a sacred visual heritage was flourishing in Quebec City, the Ursulines initiated an ornamental artistic tradition that subsequent generations of nuns and students would carry on.

Marie de l’Incarnation’s contribution to the cultural life of Quebec City remains significant to this day. Her artistic legacy endures through the Pôle culturel du Monastère des Ursulines, an organization established by the religious community in 2017 to manage its archives, collections, and museum. The Centre Marie-de-l’Incarnation, founded in 1964, continues to promote the history of the Ursulines and their founder, who was proclaimed the Mother of New France by the Quebec Parliament in the nineteenth century. Marie de l’Incarnation was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1980 and canonized by Pope Francis in 2014.

François de Laval (1623–1708)

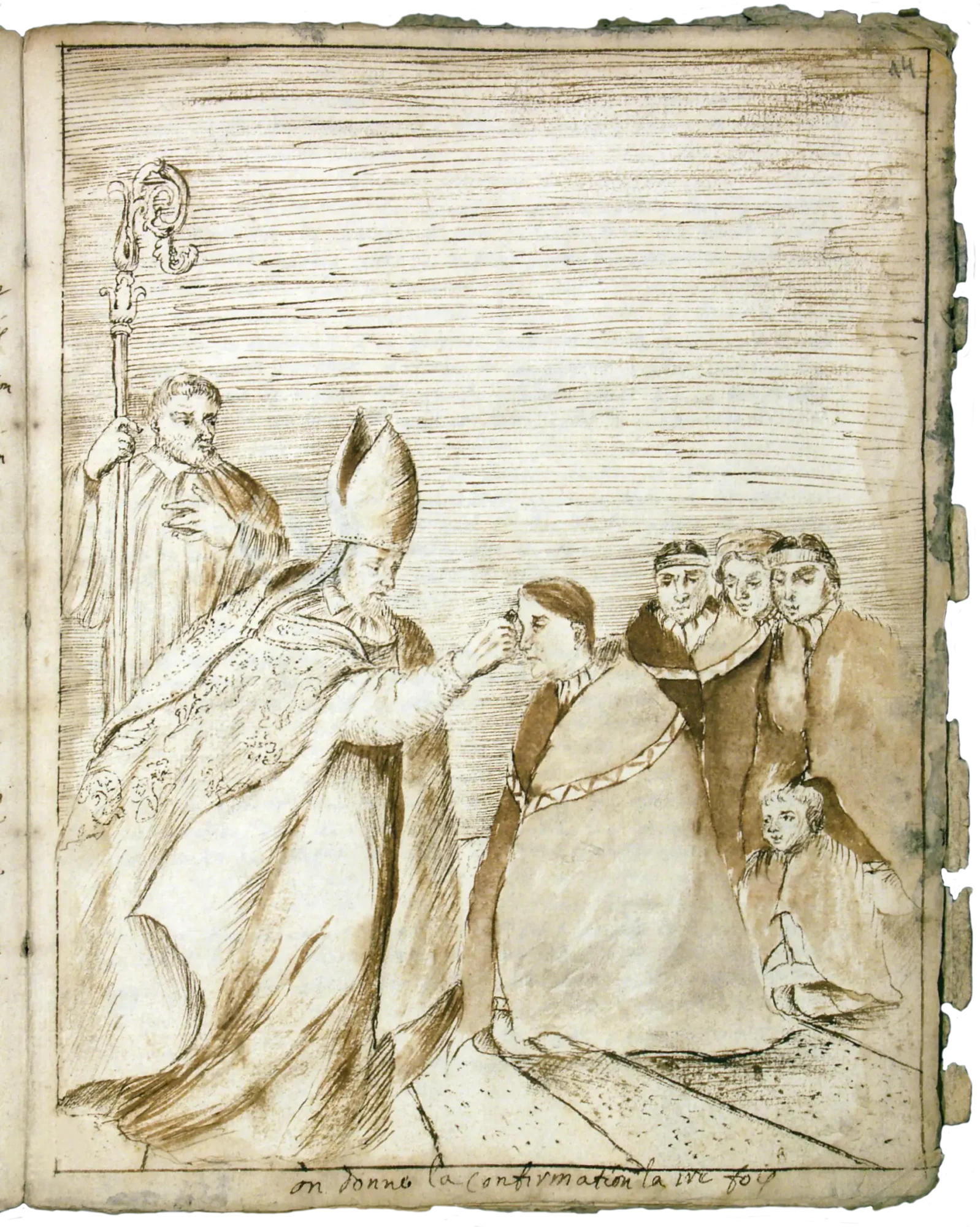

Monsignor François de Laval is regarded as the founder of the Catholic faith in New France. When he arrived in 1659, he laid the foundations of the powerful Canadian Catholic Church as a vicar, and fifteen years later, in 1674, he was granted his diocese. The first bishop of Quebec exercised his spiritual power over a network that would encompass thirty-five parishes by the end of his episcopate in 1690. In the realm of the arts, his contribution lies in his support for religious art in the city.

The construction and ornamentation of new places of worship spurred both artistic imports and local production. In this regard, the influence of Mgr. de Laval, who significantly increased the importation of sacred works from Paris and encouraged the development of local artistic careers, was fundamental. For example, during the earliest religious ceremonies in Notre-Dame de Québec, which gained cathedral status when Laval was appointed bishop in 1674, he celebrated the Eucharist using a gift from King Louis XIV: a gilded silver chalice and a paten richly adorned with scenes from the life of the Virgin.

As modest as their exteriors may be, Quebec City’s churches have remarkable interiors, adorned with sumptuous liturgical accessories crafted in Paris (paintings, sculptures, and silverworks) and designed to instruct, inspire, and sustain religious fervour. Since the Council of Trent (1545–63), richly decorated churches filled with paintings, sculptures, and sacred furnishings have embodied the divine. This perfect harmony between art and Catholic faith can be difficult to grasp in today’s pluralistic Western societies, where secularism has become a key principle of governance.

Laval also left an important cultural legacy with the founding of the Séminaire de Québec in 1663. This institution—dedicated to training priests (at the Grand Séminaire) and educating young French, Canadian, and Indigenous students (at the Petit Séminaire)—became the religious, intellectual, scientific, and artistic centre of New France.

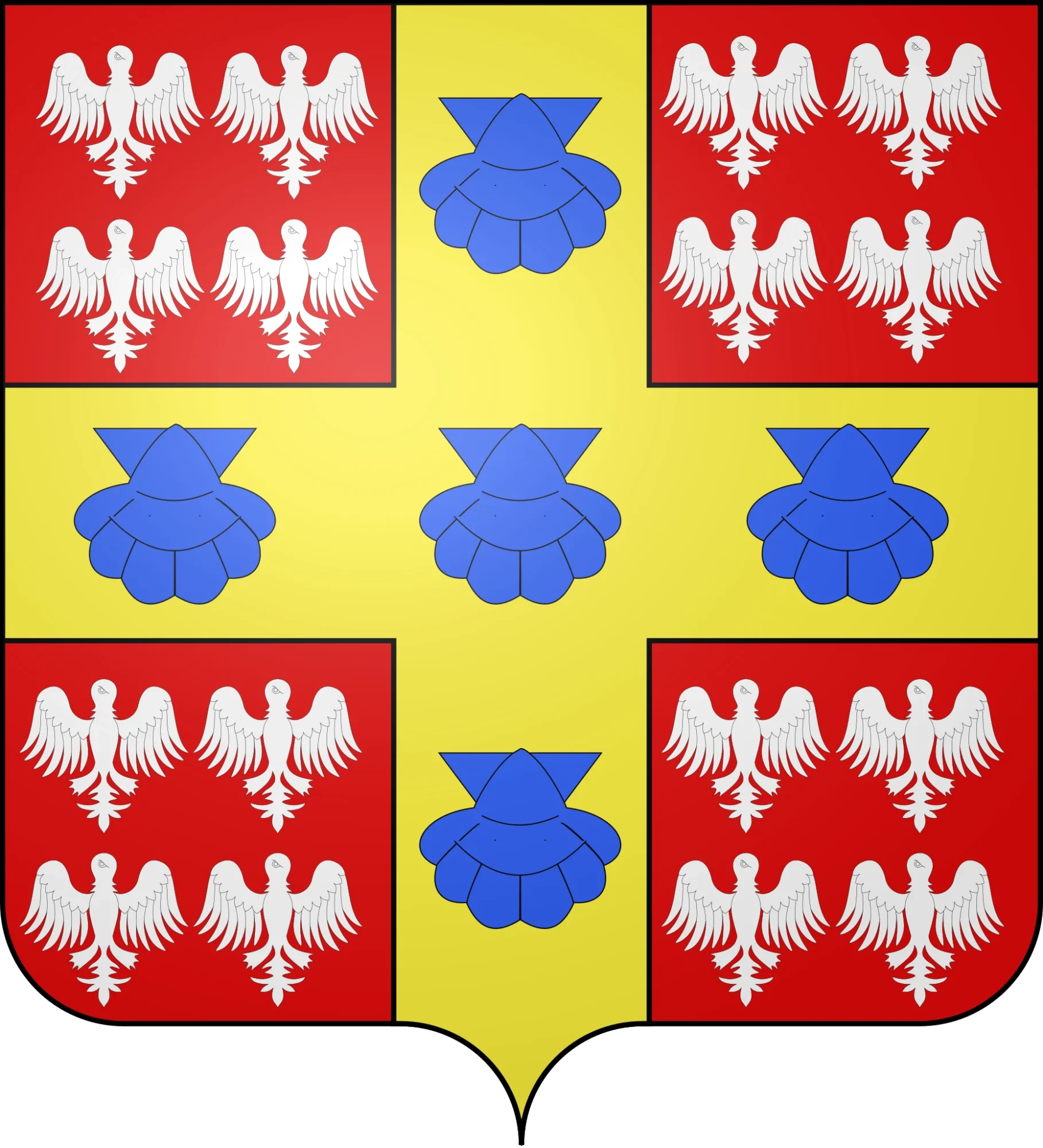

Today, the sixteen alerions, single cross, and five shells from the Laval family coat of arms continue to serve as symbolic emblems of the Séminaire de Québec and, by extension, of Université Laval, which was founded by the seminary in 1852. As the first French-language institution of higher learning in the Americas and the sixth university in Canada, it honours François de Laval through its name.

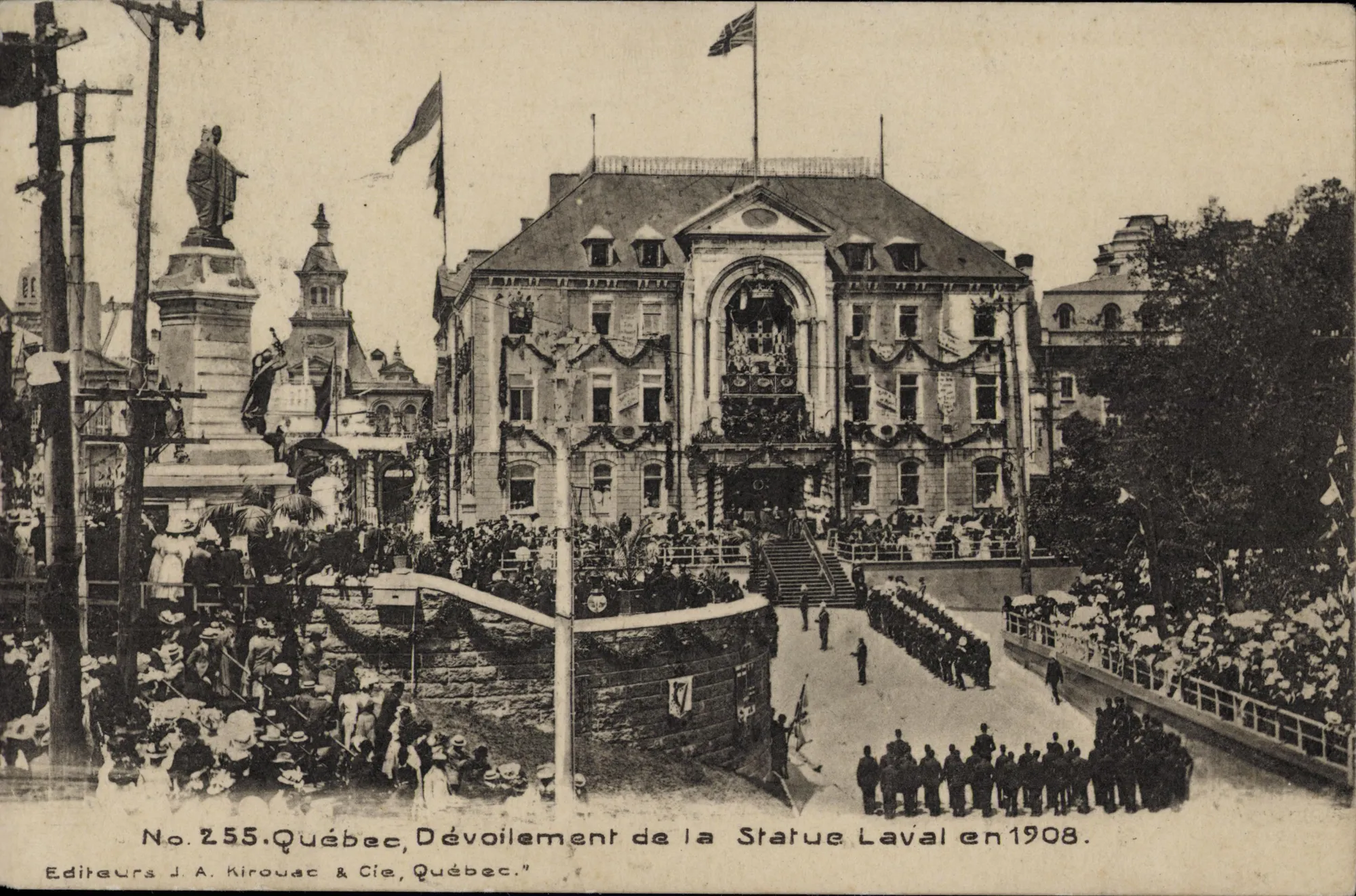

In 1908, the sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917) also honoured Laval with a majestic monument unveiled before a crowd of fifty thousand people during Quebec City’s tricentennial celebrations. In 2014, in recognition of his role as the founding father of the Canadian Catholic Church, Laval was proclaimed a saint by Pope Francis.

Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry (1682–1756)

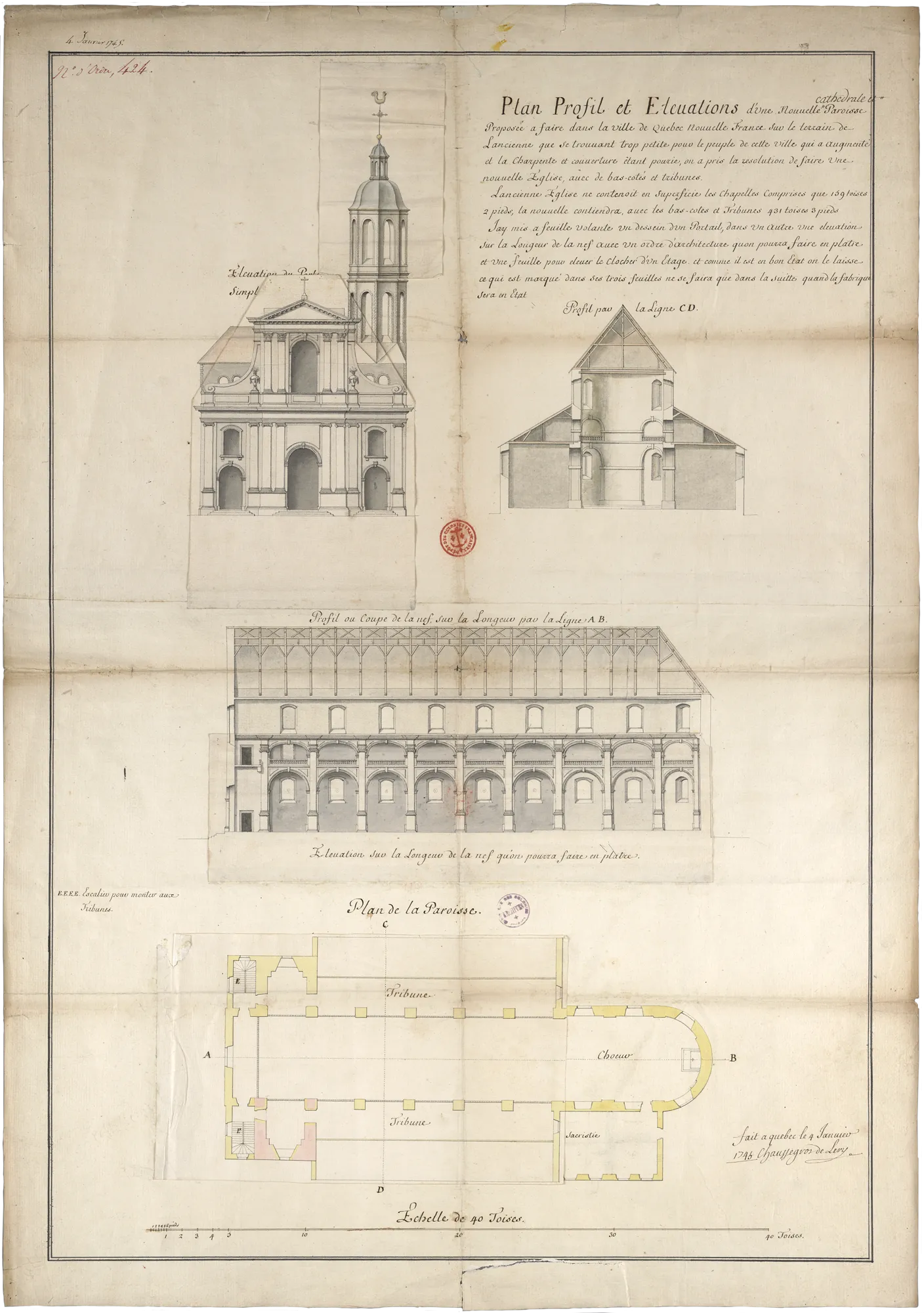

The French engineer, architect, and urban planner Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros was a patient community builder who, “through the diversity and scope of his work in military engineering, civil and religious architecture, and urban planning,” left his mark on various aspects of life in New France. His most remarkable contribution to Quebec City is undoubtedly the fortified wall of the Upper Town. He conceived it in 1716 but began to supervise its construction only in 1745.

This career military officer and son of an engineer was initially sent to Quebec City in 1716 on a temporary mission as a manager of French colonies. His task was to evaluate a fortification project designed by the general engineer of the navy, who had conceived it from France without ever seeing Quebec City. Chaussegros returned to France in 1717 with his own proposal for military defence, including drawings and plans for the fortifications and a citadel. He came back to the capital in 1719 as chief engineer to the king of France for Canada. This prestigious title led him to work not only in Quebec City but also in Montreal and Niagara. He eventually settled in the capital, marrying Marie-Renée Legardeur de Beauvais, a young woman of high colonial society whose status allowed Chaussegros to add the aristocratic “de Léry” to his surname.

The king’s chief engineer left his mark on Quebec City by successfully adapting the highly codified urban planning regulations imposed by Paris to local conditions. Pragmatic in his approach, Chaussegros de Léry proposed residential construction measures suited to the climate, fire risks, and sanitation challenges of the city. These measures gave rise to an urban landscape characterized by a style of French Classicism marked by uniformity and simplicity: dual-pitched roofs instead of mansard roofs, simplified wooden frameworks, firewalls, masonry floors, and a lack of wooden ornamentation, among other features. This rational architecture did not always win the favour of the colony’s elites, who were deeply influenced by the codes of Parisian court society and eager to emulate its opulence.

Chaussegros de Léry’s work in Quebec City is also evident in the architecture of symbols of power, both civil and religious. On the civil side, he undertook a renovation of Château Saint-Louis, the governor general’s official residence in the city, completed in 1723. On the religious side, he designed the plans for and oversaw the expansion of Notre-Dame de Québec Basilica-Cathedral starting in 1744. But it is his contributions to military architecture that are the most recognized today. The engineer’s patience was severely tested when it came to his plans for the city’s fortifications.

Meanwhile, his citadel project on the heights of Cap Diamant took shape only in the 1820s, a century after the engineer had drawn up the plans. Thanks to Chaussegros de Léry’s fortified wall, which still stands in the capital today, the Historic District of Old Quebec was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985.

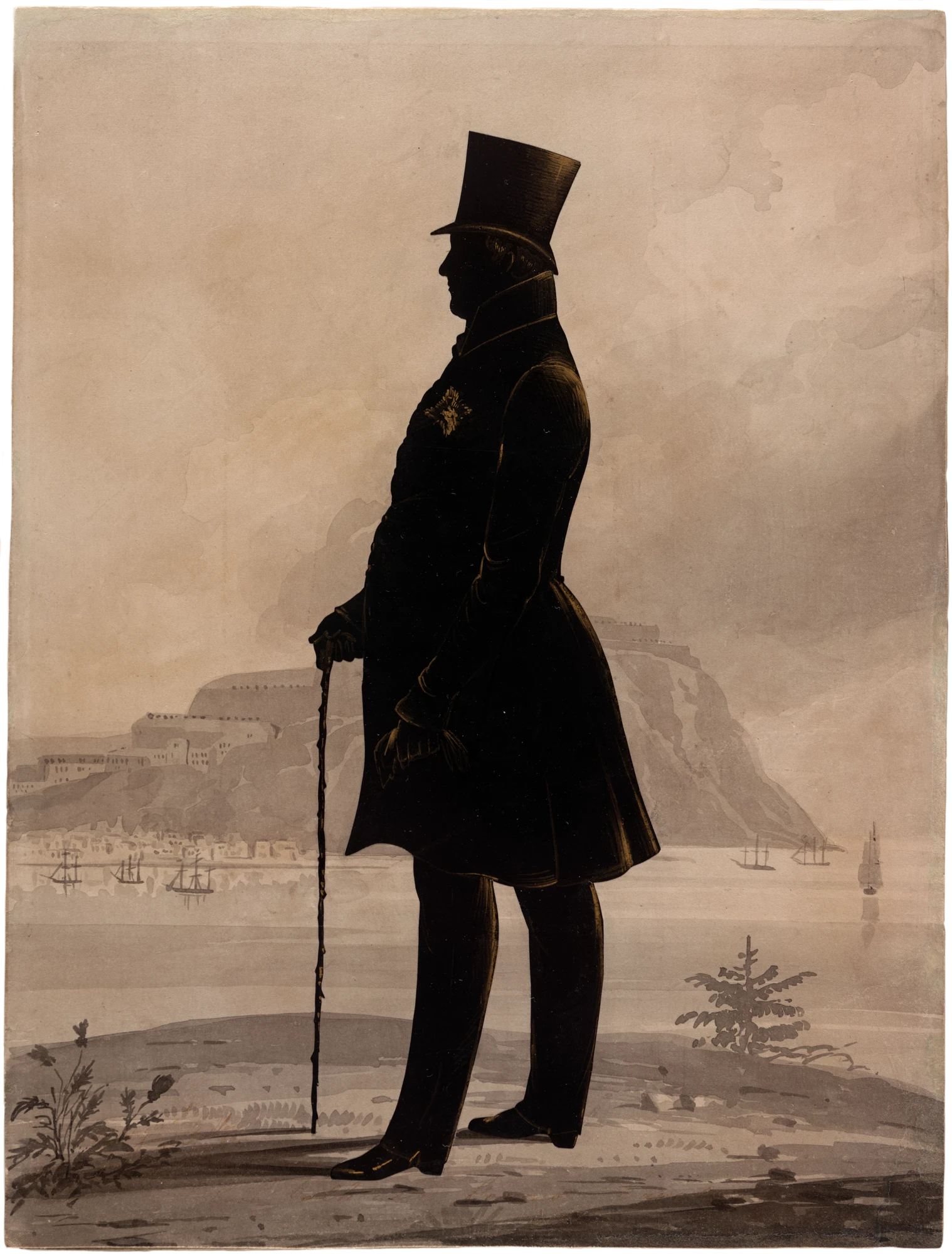

George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie (1770–1838)

Lord Dalhousie, governor general of Upper and Lower Canada from 1820 to 1828, governed the colony from Quebec City, where he became one of the capital’s most progressive community builders. The full-length portrait by the American silhouettist Jarvis Frary Hanks (1799–1853) beautifully captures the commanding presence of this high-ranking leader, depicted against the instantly recognizable landscape of the city. After the Catholic Church, Lord Dalhousie can claim the distinction of being the first true patron and art collector in Quebec City in the nineteenth century.

From the outset, the Scottish aristocrat detested the capital, with its narrow, dirty, and noisy streets, which reminded him of Paris—not to mention the old Château Saint-Louis, built in 1647, whose “filthy state” and “the wretched condition of its furniture” seemed unworthy of the governor general of the British Empire’s American dominions. During Lord Dalhousie’s eight years in office, the official residence underwent a transformation: its rooms were furnished and decorated in a contemporary style and its walls adorned with paintings and prints. Driven by keen curiosity and a passion for architecture and the visual arts, the colony’s viceroy introduced a progressive influence into various aspects of the intellectual, scientific, and artistic life of the capital. His actions created a breach in the narrow hold long exercised by the Catholic clergy. At Lord Dalhousie’s urging, Canada’s first English-language literary society, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, was founded in 1824.

To better understand the new territories he governed, Lord Dalhousie surrounded himself with topographic artists, primarily English-speaking Scots or Britons, who accompanied him on his travels to document Canada’s landscapes and features through drawings. The career military officers John Elliott Woolford (1778–1866), James Pattison Cockburn (1779–1847), and John Crawford Young (c.1788–1859) worked closely with Lord Dalhousie and his entourage, who avidly collected their works. It was Young who designed the obelisk commemorating the deaths of the Marquis de Montcalm and Major-General James Wolfe during the Battle of the Plains of Abraham—a monument that Dalhousie unveiled on the day of his final departure from Quebec City.

Charles Ramus Forrest (c.1786–1827) was also among Lord Dalhousie’s favourites during the two years he spent in Quebec City, from 1821 to 1823. The watercolourist brought a unique modernity to the capital’s panoramas with his ability to capture their picturesque qualities and beauty in luminous, clear, and highly stylized compositions. The Scottish-born James Smillie Jr. (1807–1885) arrived in the capital at the age of fourteen with his artistically gifted family; he became the city’s first engraver and took advantage of Lord Dalhousie’s patronage to perfect his engraving skills in London, England. Upon his return, Smillie engraved views by Cockburn and Young and contributed to the publication of Picture of Quebec (1829), the city’s first illustrated guidebook.

On the francophone side, Lord Dalhousie was focused exclusively on the master silversmith Laurent Amiot (1764–1839), from whom he commissioned several works during the 1820s. Notably, it was to Amiot that Lord Dalhousie entrusted the design of the Coupe présentée à George Taylor (Cup Presented to George Taylor), 1827, for the launch of the ship Kingfisher. This piece, without parallel in local silverwork during the first half of the nineteenth century, was the result of a collaboration involving Amiot and the sculptor François Baillairgé (1759–1830), who is believed to have designed the cup’s unicorn-head handle, and Smillie, who is thought to have engraved the main face of the vessel. This object is a perfect embodiment of the vitality sparked by Lord Dalhousie within Quebec City’s nineteenth-century visual arts scene.

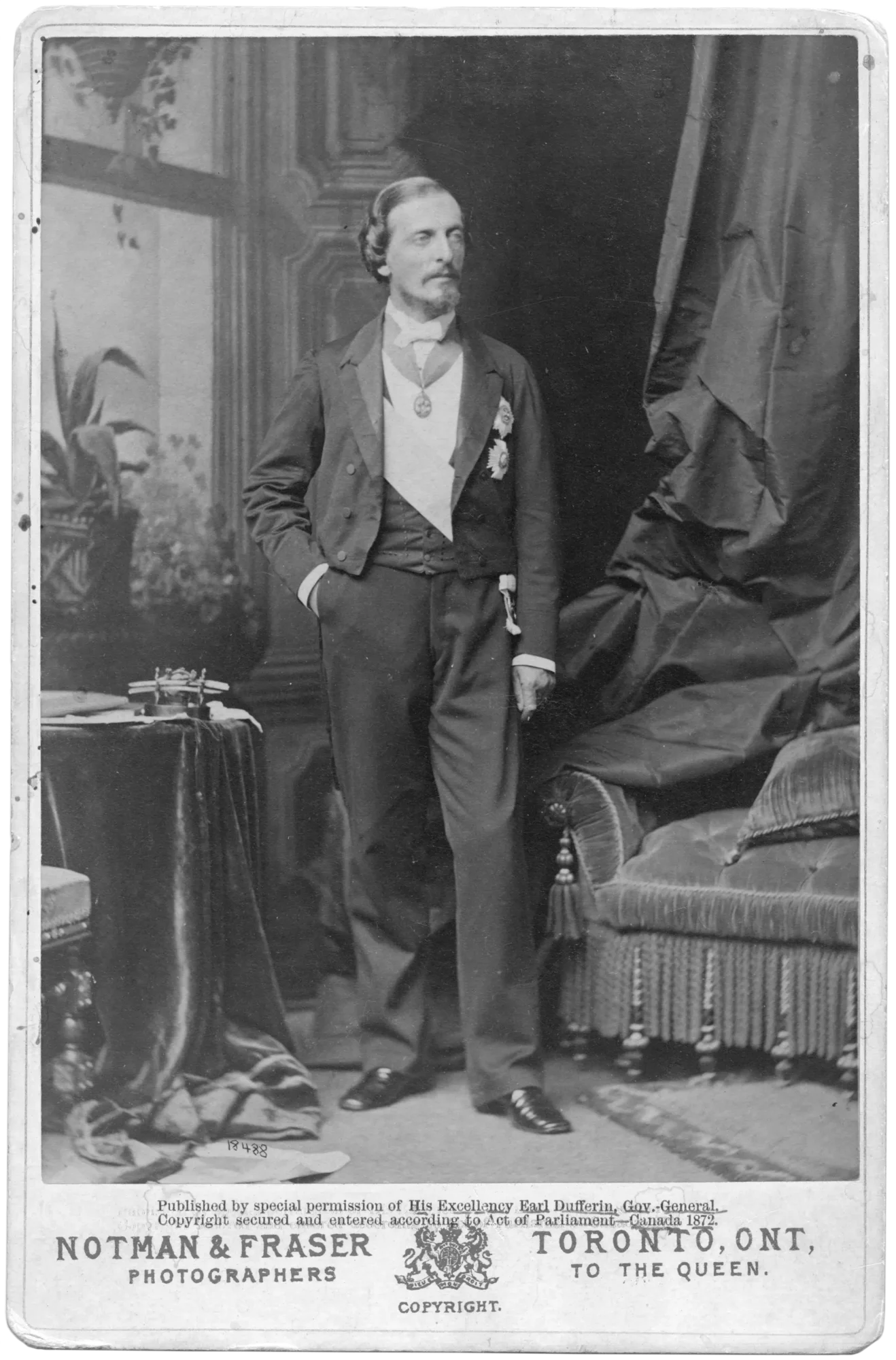

Frederick Temple Hamilton Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin (1826–1902)

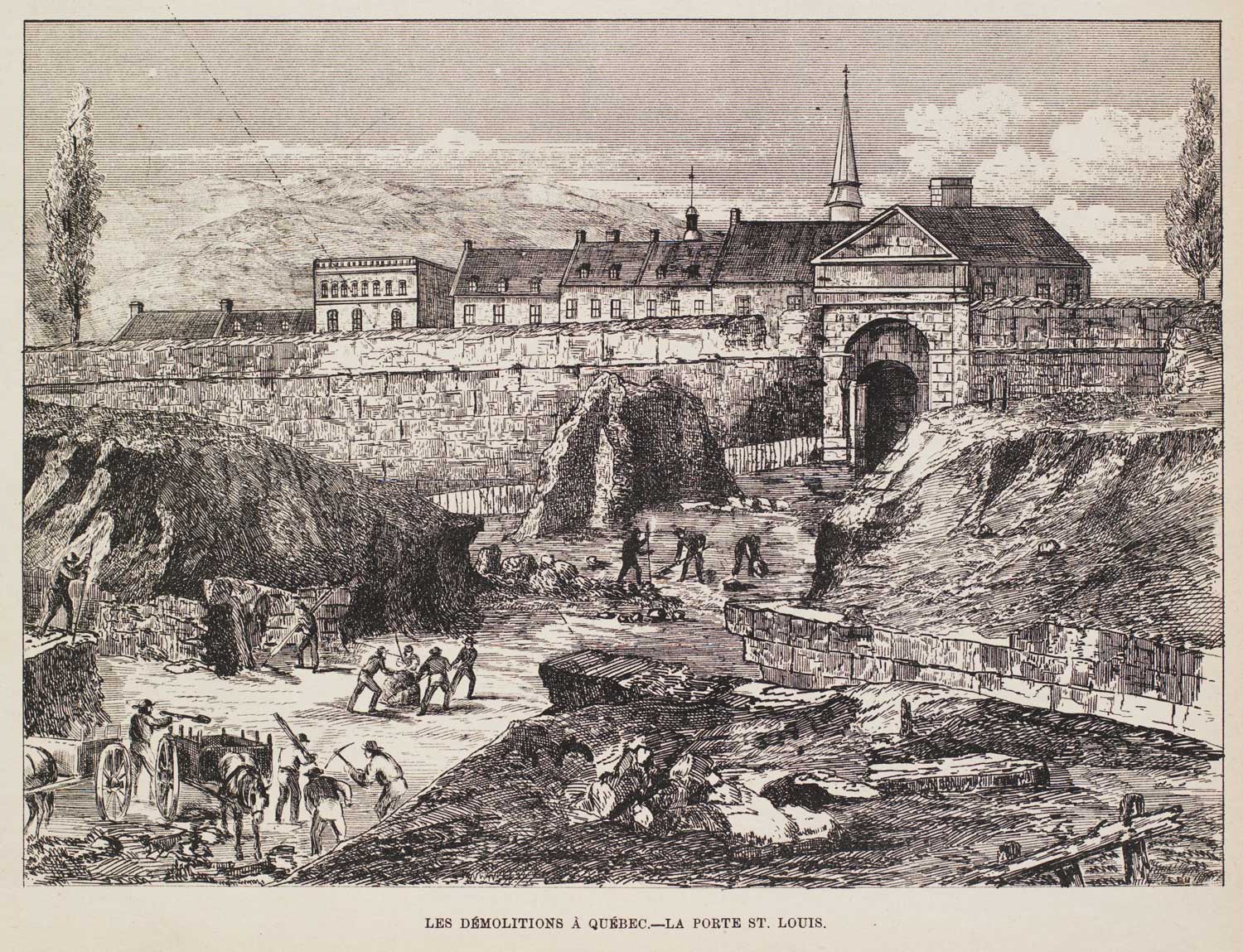

Lord Dufferin, the newly appointed governor general, arrived in the recently formed Dominion of Canada in 1872. At that time, Quebec City was in such a state of disrepair that it required a facelift and modernization to be worthy of its status as the seat of the provincial government. As the representative of Queen Victoria in Canada, Lord Dufferin strengthened ties between the city and Great Britain by raising the funds needed for its restoration. In this way, Lord Dufferin contributed significantly to Quebec City’s enhancement in the late nineteenth century.

Lord Dufferin’s tenure is largely defined by his reaction to the destruction of Quebec City’s heritage through the indifference of the local authorities. After the British garrison left the city in 1871, the defensive military structures, including the walls and gates surrounding the old city, were deemed unnecessary. Four access gates (Prescott Gate, Palais Gate, Hope Gate, and Saint-Louis Gate) were demolished because their passageways were thought to be too narrow for the traffic leading to the new activity centres expanding outside the city. In 1875, Lord Dufferin—scandalized by the degradation of the capital’s historical wealth—created a beautification plan, tailored to the needs of a modern city. His vision included wider gates, an extension of the terrace on Cap Diamant, restoration of the walls, and the creation of a pedestrian-friendly rampart walk encircling the old city.

Under Lord Dufferin, the Citadel became the governor general’s summer residence—and a place where he regularly stayed. He was also instrumental in promoting the Château style that would come to define the architecture of Old Quebec, most notably with the Château Frontenac inaugurated in 1893. At Dufferin’s request, the terrace in front of the hotel—originally built in 1838—was extended according to plans devised by the engineer and architect Charles Baillairgé (1826–1906), who quadrupled its length. Inaugurated in 1879, the spectacular promenade, now known as Dufferin Terrace, was adorned with pavilions and offered a highly picturesque view of the St. Lawrence River, drawing the eye westward to the tip of Île d’Orléans and Montmorency Falls. This unique panorama continues to captivate both locals and tourists from around the world today.

Even though Quebec City belonged to the modern Renaissance era and was shaped by flourishing French Classicism, Lord Dufferin was captivated by the Middle Ages and by Romanticism. With the architect William H. Lynn (1829–1915), he staged a mythical medieval atmosphere for the city, dramatizing its military past, its stone walls sheltering convents and monasteries, and its gates with their neo-Gothic ornamentation reminiscent of European castles and the French city of Carcassonne (restored by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) in the mid-1800s). Inspired by this picturesque aesthetic, Lord Dufferin envisioned Quebec City as a future tourist destination and aimed to imbue it with a romantic aura. His decision to rebuild the city’s fortifications and gates would, a century later, become the principal reason for Old Quebec’s inclusion on the prestigious UNESCO World Heritage List.

Louis-Athanase David (1882–1953)

From 1919 to 1936, Provincial Secretary Louis-Athanase David was the architect of Quebec’s first cultural policy. He implemented a series of measures that endowed the capital with major cultural institutions. His three-fold vision was to “form an artistic elite to guide our people’s tastes toward beauty,” to “express the soul of a people through enduring works,” and to “offer artists—whether musicians, sculptors, or painters—the necessary encouragement for their creations.” David began with the idea of a national museum, but his ambitions grew to creating literary prizes, expanding education, awarding scholarships, and more. His policies led to the establishment of the first public fine arts school in Canada, the École des beaux-arts de Québec, inaugurated in 1922, and the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts de Québec), which opened in 1933.

The French model dominated in Quebec City since the early days of colonization in the seventeenth century, and it was this artistic tradition that David strongly believed in and linked to the cultural identity of French Canada. The academic tradition and French art were thus favoured as the primary references in art education in the city. In the 1800s, when the city had no art school, those who were interested in pursuing a professional career often had to go to France to complete their training. For David, “drawing on Quebec’s French past” provided a foundation for establishing “the North American specificity” of the province. The artists Alfred Pellan (1906–1988) and Omer Parent (1907–2002) and the art historian Gérard Morisset (1898–1970) were among those who benefited from enhanced scholarships for studying abroad, which allowed them to pursue training in Paris.

An idealist, David seemed intent on “creating a vision for Quebec’s cultural development.” The Provincial Museums Act of 1922 called for the establishment of two museums dedicated to the study of history, science, and fine arts: one in Quebec City and one in Montreal. Ultimately, only the Musée de la province de Québec, built on the Plains of Abraham, came to fruition. David served on the jury responsible for selecting the artworks that would form the core of the national collection in the new museum, which opened its doors in 1933. These initial acquisitions, made as part of a government program to support the arts, shared a unifying theme: Quebec’s landscapes—both urban and rural—depicted under snowy conditions.

One of these first purchases, Le pont de glace à Québec (The Ice Bridge in Quebec), 1920, by the Montreal painter Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942), offers an Impressionist vision of the Quebec landscape. “The term ice bridge refers to a marked passageway on the frozen surface of the St. Lawrence River. When the most well-known of these formed between Québec and Lévis, it was a festive event. It facilitated economic exchanges and unique social interactions.” The line of sleds crossing the bridge are brought to life with vivid colours, and the background is rendered in an Impressionist style, dotted with luminous strokes of paint. This work was selected not only to showcase the beauty of the land but also to define “a painting of the French-Canadian soul.” This idea, which aligned with David’s political vision and his nationalist convictions, would also guide the future museum.

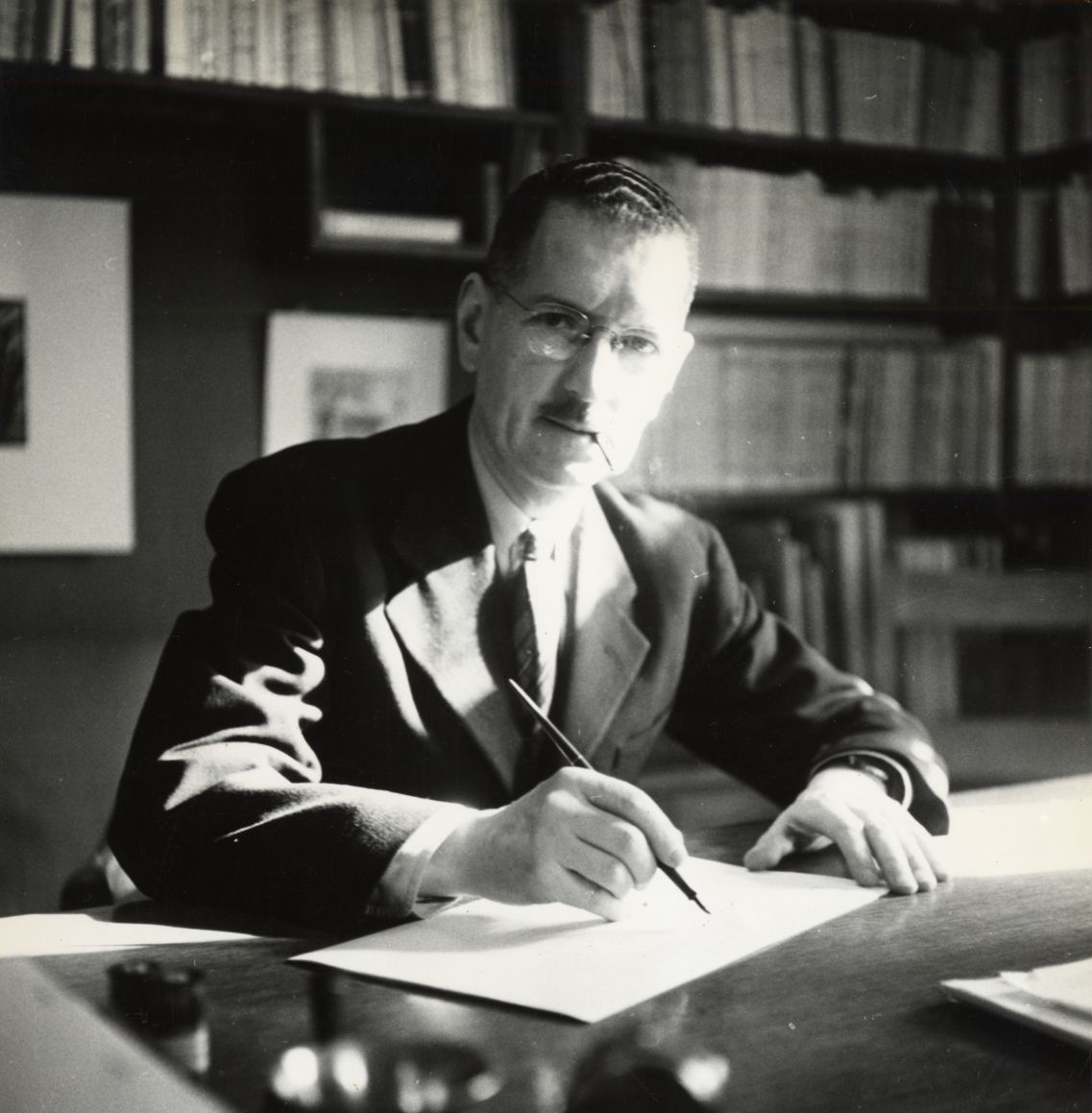

Gérard Morisset (1898–1970)

The scholarly community builder Gérard Morisset distinguished himself in the capital as the first adjunct professor of art history courses at the Faculty of Arts at Université Laval in 1952 and as director of the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) from 1953 to 1965. Morisset laid the foundations for the discipline of art history in the province, steering it toward professionalization. His legacy is so profound that one of the prestigious Prix du Québec awards was named in his honour in 1992.

A staunch defender of the ideology of resistance to modernity, Morisset continuously nurtured a mythical vision of New France, which he viewed as an extension of the motherland. With passion and nostalgia, he constantly recounted the story of a rich past whose precious artifacts, victims of ignorance and neglect, were under threat of disappearance. He successfully persuaded government authorities of the need to preserve heritage assets. From 1937 to 1969, he worked on a comprehensive inventory of the province’s artworks. The ambitious project marked the beginning of art historical practice in the province.

The inventory stands as one of Morisset’s most significant contributions to the history of Quebec art. He led a small team that conducted fieldwork across the province, with the goal of creating a systematic and reasoned record of all works of art in Quebec—from the major arts (architecture, sculpture, painting, and silversmithing) to the minor (ironwork, bookbinding, cabinetry, pottery, domestic crafts, and chasuble-making). The project emphasized the value of traditional French Canadian heritage and assembled an impressive “wealth of information through object studies, archival research, interviews with individuals preserving oral memories of places, and documentary searches in available publications, particularly parish monographs.” Morisset’s inventory did not, however, address Indigenous art and paid little attention to the province’s artistic production from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The next generation of art historians, trained in universities and “often influenced by the cultural and social approaches developed starting in the 1960s,” would soon work to fill these gaps.

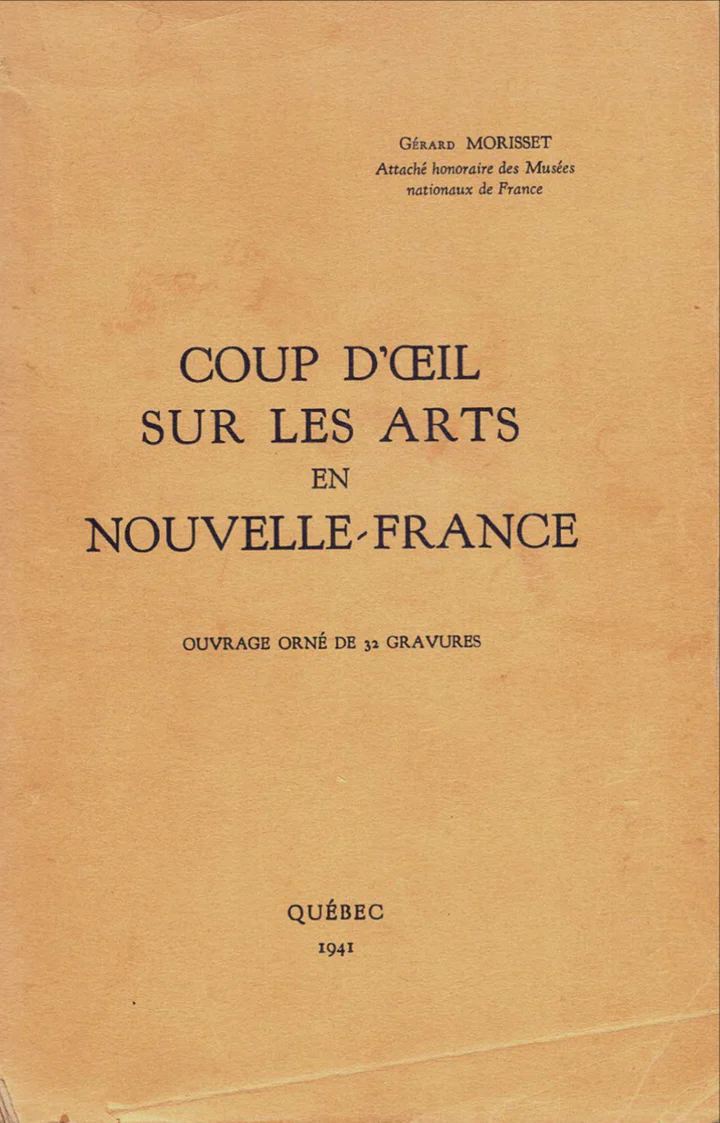

For Morisset, the Inventaire des œuvres d’art du Québec was never an end in itself but rather a means to interpret and disseminate the history of art in the province. It is difficult to overstate the scope of his achievements in outreach and popularization. “Drawing on the extensive information he gathered, Morisset self-published ten books on the arts in Quebec during the 1940s and 1950s, including his first survey, Coup d’œil sur les arts en Nouvelle-France (1941),” and he also contributed to twenty-five collective works and wrote some 160 newspaper articles and 145 journal articles up to 1968. He delivered hundreds of lectures and hosted radio talks in 1941 and 1942. Beginning in 1944, Morisset participated in a radio series, La voix du Canada, aimed at a European French audience and broadcast via shortwave until 1953. His dedication to the history of art established him as one of the most prominent intellectuals in the province.

Morisset’s contributions to Quebec City were most notable through his decade-long role as the director of the Musée de la province. The nationalism he so passionately championed was reflected in numerous acquisitions of both historical and modern Quebec art for the museum’s collections, as well as in exhibitions that toured Canada and abroad. The museum’s first building has been called Gérard-Morisset Pavilion since 1991. In 1992, the Prix Gérard-Morisset—given to individuals for their efforts to preserve Quebec’s cultural heritage—was established. Today, it is one of several awards of the prestigious Prix du Québec, awarded annually by the provincial government.

Jean-Paul L’Allier (1938–2016)

As mayor from 1989 to 2005, Jean-Paul L’Allier is regarded as a key builder of Quebec City’s identity as a cultural capital in the twenty-first century. His impact on the arts in the city is immense, and his legacy is still clearly visible decades after his time in office. The son of a baker, L’Allier had a distinguished career as a legal educator, diplomat, and provincial politician in Robert Bourassa’s 1970s Liberal government before he was elected the capital’s thirty-fifth mayor. The city was transformed under his administration, and culture became the central pillar of its development.

The economic and urban revitalization that L’Allier brought to Quebec City is best symbolized by the Saint-Roch district. For nearly a century, from 1865 to 1960, rue Saint-Joseph had been the major commercial and entertainment artery of the neighbourhood—so much so that it was nicknamed the Broadway of Quebec City. But like so many streets in cities all over North America, it fell victim to urban flight. In the 1970s and 1980s, rue Saint-Joseph was in decline, and the Saint-Roch neighbourhood languished, its once-vibrant shops and restaurants replaced by parking lots and empty storefronts. The one bright spot was that artist-run centres and alternative galleries began to flourish in the area, taking advantage of the low rents in a struggling neighbourhood.

As revitalization efforts took hold in the 1990s and 2000s, L’Allier oversaw the creation of a large urban park, which was named in his honour in 2017. Bordering this park, two major hubs of artistic activity were established. On côte d’Abraham, the Méduse complex (1993) brought together various artist-run centres. Further east, on boulevard Charest, a former corset factory dating back to the late nineteenth century was restored and turned into a home for Université Laval’s École d’art (1993). Equipped with numerous studios, workshops, and creative laboratories, the industrial-style building stands as one of the most remarkable landmarks in the district.

Under L’Allier’s administration, public art also proliferated in the capital in the early 2000s. The alternative art spaces that had first begun to appear in the 1970s reached their full potential during his tenure. Éclatement II (Burst II), 1998, a massive fountain by the sculptor Charles Daudelin (1920–2001), was built during this revitalization period. Evoking the collision of tectonic plates and the importance of water to Quebec City’s economy, the monumental work draws inspiration from another of Daudelin’s fountains, Fontaine l’Embâcle (Ice Dam Fountain), 1984, which he created for Place du Québec in Paris.

Because of the development fostered by L’Allier, a network of diverse enterprises—ranging from theatre, cinema, advanced technology, and video games to business and urban planning schools—began to emerge, forming a vibrant and youthful urban fabric. This transformed the Saint-Roch district into a trendy hub and Quebec City’s new cultural quarter in the 2000s. L’Allier’s success at bringing together urban development, culture, and heritage is recognized worldwide. Every two years since 2009, the Organization of World Heritage Cities has awarded the Jean-Paul L’Allier Prize for Heritage to a member city distinguished by its achievements in the conservation, enhancement, and management of a property listed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

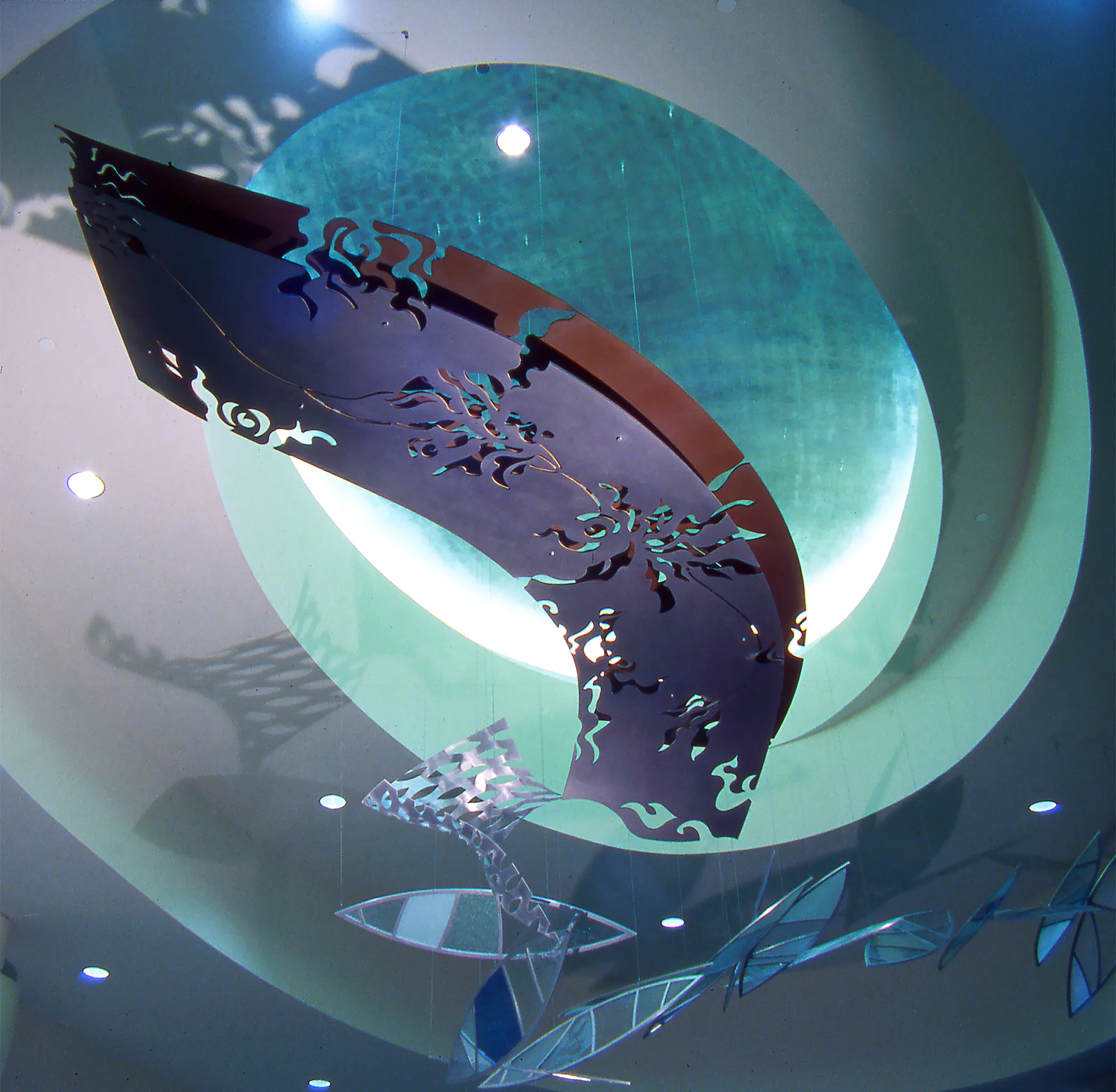

The Simons Family

In modern societies, commerce and fine arts are inextricably linked. While art comfortably occupies its own market niche at the top of our socio-economic pyramid, the fusion of the two sectors sometimes creates a new and dynamic space—such as happened with the Maison Simons department store chain in Quebec City. For decades, the Simons family, one of the great cultural patrons of the capital, has contributed to the promotion of art by encouraging appreciation for the city’s architectural heritage, enriching its urban landscape, and fostering a passion for contemporary visual arts in its stores. La cime (Treetop), 2018, by Giorgia Volpe (b.1969)—a work of public art commissioned by the Simons family for their store at Galeries de la Capitale—exemplifies this commitment.

Taking the form of a tree seemingly unfolding from the ceiling, with branches covered in papier-mâché and repurposed fabrics, Volpe’s work evokes the delicate nature of both the environment and the social fabric. The Simons family has woven itself into the social fabric of Quebec City and now enjoys a reputation that extends far beyond the province’s borders. The company’s success, even its prosperity, is deeply rooted in the history of the first commercial artery of the Upper Town, côte de la Fabrique, which was laid out by the surveyor-engineer Jean Bourdon (1601–1668) in 1640. The Maison Simons headquarters at 20 côte de la Fabrique—once the site of a seventeenth-century tavern and later a nineteenth-century haberdashery—was founded in Quebec City in 1840 and remains an exceptional heritage gem.

Gordon Donald Simons (1929–2018) was the driving force behind the fusion of retail and fine arts. A passionate supporter of culture, he championed everything from the Opéra de Québec and the Orchestre symphonique de Québec to the Quebec Winter Carnival. His enthusiasm for the visual arts was passed on to his sons, Peter and Richard Simons, who have managed the Old Quebec business since 1996, overseeing an expansion across Canada. “Whether through architecture, design, or visual arts, each of our stores is an opportunity for you to learn about an exceptional local artist and for us to share the art we love best.”

One of those local artists, Danielle April (b.1949), created the work Au fil d’une vie (Thread of a Life), 1999, for the Maison Simons store in Sherbrooke. Its sinuous, translucent forms are suspended from the store’s illuminated ceiling, much like the minimalist mobile sculpture Solstice, n.d., by Guido Molinari (1933–2004), in the grand Simons store in downtown Montreal.

Once found exclusively in churches, art—from minimalist landscape sculptures to paintings to animated colourful murals in glass—now reaches crowds of faithful consumers in the refined spaces of Simons stores. In addition to facilitating these unexpected encounters between contemporary art and shoppers browsing for bargains, the company has been developing a new online marketplace called Fabrique 1840 since 2018. This platform showcases the work of hundreds of Québécois and Canadian artisans, using a name that nods to the nineteenth-century origins of the Simons family business. The family itself remains firmly grounded in the present, though, embracing both art and craftsmanship in their physical and virtual stores, which serve as the new temples of the modern consumerist era.

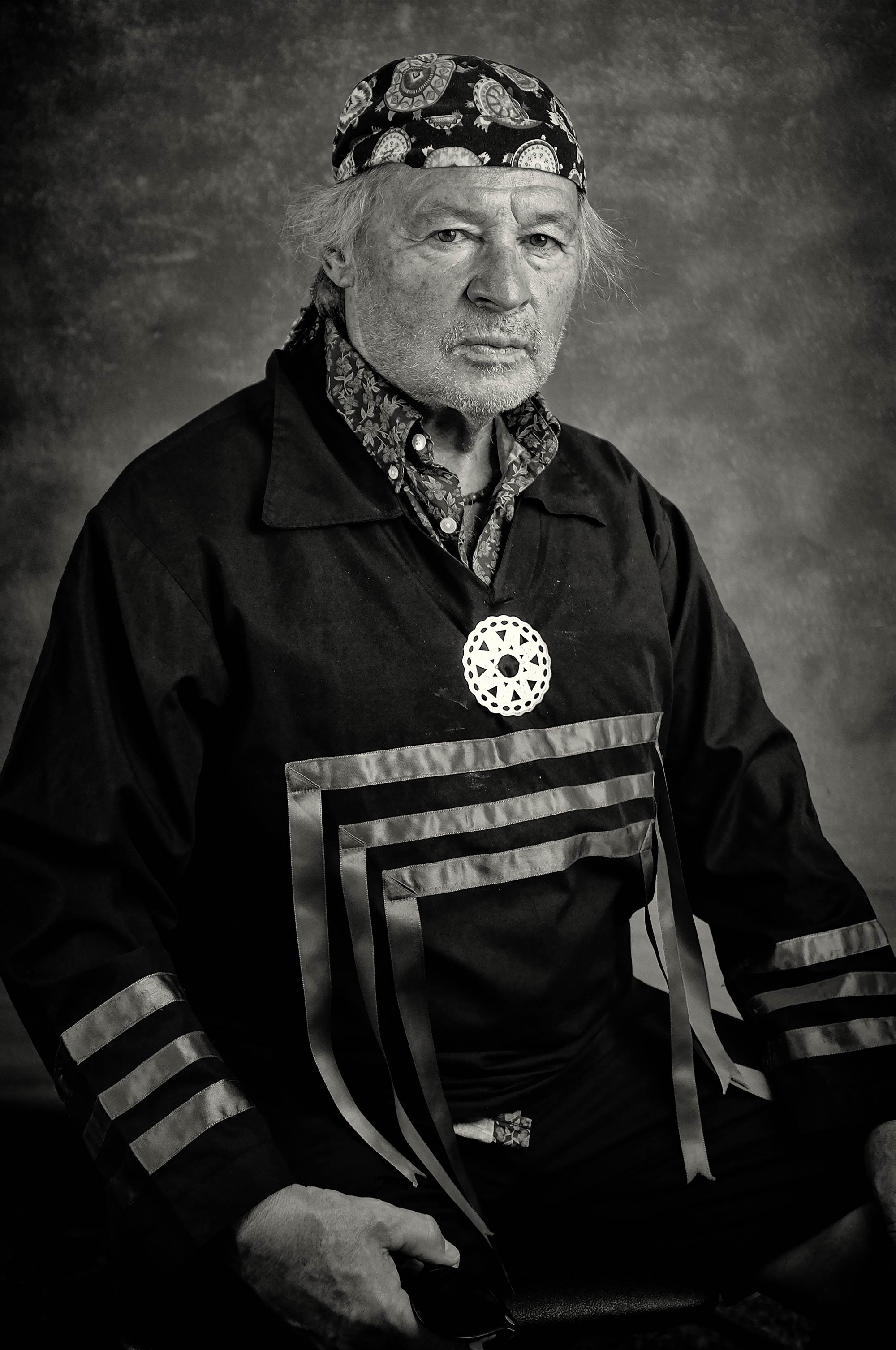

Guy Sioui Durand (b.1952)

The sociologist, performance artist, art historian, poet, and educator Guy Sioui Durand is one of the most dedicated builders of the contemporary Quebec art scene as it has evolved over the past half-century. His vision, deeply rooted in his Wendat culture and concerned with community self-determination and ideological self-management, has helped shape Quebec City’s network of alternative galleries, now known as artist-run centres.

During his sociology studies, Sioui Durand forged a lasting partnership with the publisher and activist Richard Martel (b.1950). In 1978, they co-founded the magazine Inter, art actuel, a publication that remains active to this day. Sioui Durand has been a significant contributor, focusing on contemporary art practices such as performance, installation, poetry, and multimedia. His rational and avant-garde critiques have established him as one of the most respected advocates for politically engaged experimental art that challenges the institutional and capitalist models of contemporary society. In 1997, Sioui Durand published his doctoral thesis as L’art comme alternative, a substantial essay that became a landmark in the historiography of art in Quebec. In the book, he examines the emergence and proliferation of artist-run centres and collectives throughout Quebec from 1976 to 1996.

Sioui Durand is at the forefront of the significant movement advocating for the recognition of harms caused to Indigenous Peoples by assimilation, destruction, and discrimination. He leverages his experience as an educator in service of the Kiuna Institution, an Indigenous college located in the Abenaki community of Odanak in central Quebec. In 2011, this pioneering college began offering the province’s first college-level diploma program focused on revitalizing the culture, languages, and traditions of First Peoples.

Sioui Durand’s art historical writings also offer incisive analyses of the work of Indigenous artists, such as Caroline Monnet (b.1985) and Kent Monkman (b.1965), and non-Indigenous artists, notably Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002). Sioui Durand has highlighted Riopelle’s ability “to see, decode, and memorize every significant fragment, every human or animal trace of a territory, weaving them into his creations.” He underscores Riopelle’s deep affinity with Indigenous knowledge tied to the land and its topography, as exemplified in L’étang—Hommage à Grey Owl (The Pond—Homage to Grey Owl), 1970, a work dedicated to the legendary trapper and set against the dense and luminous vastness of the Canadian forest.

After he participated in the exhibition Yahndawa’ : Portages entre Wendake et Québec (Yahndawa’: Portages between Wendake and Quebec), 2023, at the Huron-Wendat Museum, Sioui Durand co-founded, with Teharihulen Michel Savard and Manon Sioui, Ahkwayaonhkeh, the first Wendat artist-run centre in Quebec City, housed within the Méduse co-operative. “In its first year, Ahkwayaonhkeh presented four exhibitions exploring the motif of the moccasin, paying tribute to the centre’s name, which means ‘at the old moccasins.’” Today, the visionary builder continues to weave connections between Quebec City’s French and Indigenous communities, shifting perceptions and practices in ways that transform—and even “rewild”—creative territories through the collaboration of all involved.

Robert Lepage (b.1957)

The versatile, groundbreaking, and unifying community builder Robert Lepage finds his anchor in his multidisciplinary creation, production, and performance company, Ex Machina, founded in Quebec City in 1994. A playwright, actor, director, and filmmaker, Robert Lepage is a native of the capital and was raised in a modest family home in the Montcalm neighbourhood. After studying acting at the Conservatoire de Québec from 1975 to 1977, Lepage travelled to Paris in 1978 to continue his education under the French director Alain Knapp (b.1936), whose teaching emphasized improvisation, play, and collective creation. Throughout his acclaimed career, Lepage has consistently applied these principles and has influenced progressive creative circles not only in Quebec City but throughout the province.

The 1980s marked a breaking down of barriers between artistic practices, fostering the creation of multidisciplinary works. This helped shape the early work of Lepage, whose creations straddled the boundaries between the performing arts, theatre, performance, and the visual arts. In 1994, Lepage founded Ex Machina, a company with a theatrical focus characterized by its openness to a diversity of genres and its strong reliance on new technologies. Ex Machina blends the performing arts—dance, opera, and music—with recorded arts such as cinema, video, and multimedia.

Moulin à images (Image Mill), 2008–14, a spectacular architectural projection and a highlight of the celebrations for Quebec City’s four hundredth anniversary, exemplifies this intersection of disciplines. Lepage’s most recent work, Le projet Riopelle (The Riopelle Project), 2023, created to mark the centenary of the birth of Jean Paul Riopelle, continues this tradition. The four-hour play presents thirty tableaux vivants inspired by Riopelle’s life, each one a small masterpiece of visual ingenuity. The stage showcases Lepage’s boundless creativity: at one point, the scene transforms into a dazzling painting from Riopelle’s series Icebergs, 1977, a visual memory of the icebergs the painter had seen from a seaplane with his friend Champlain Charest. The play also recalls pivotal moments in Quebec’s history, such as the signing of the Refus global manifesto by the Automatistes, including Riopelle, in 1948.

In 1997, Lepage founded the Caserne Dalhousie, a multimedia production centre located in a former fire station on rue Dalhousie, a heritage building with eclectic architecture. In 2019, Lepage and Ex Machina moved to the newly established Le Diamant Theatre, on Place D’Youville at the entrance of Saint-Jean Gate. Lepage could not have imagined a better setting for his “diamond” than Quebec City, which he describes as “a city of creation: that is its wealth, with increasingly bold and diverse artistic offerings.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements