Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin (1815–1886)

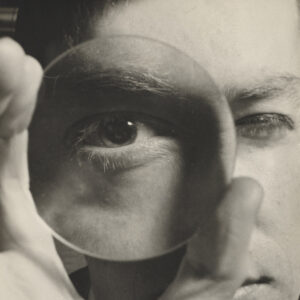

Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin, Zacharie Vincent et son fils Cyprien (Zacharie Vincent and His Son Cyprien), c.1852–53

Oil on canvas, 48.5 x 41.2 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin was born in 1815 in the village of Jeune-Lorette (now Wendake), northwest of Quebec City, and grew up in a family of chiefs committed to the traditions of their nation. Throughout his life, he fought against the decline of Wendat culture and language, which had been weakened by more than two centuries of European occupation and colonialism. His community gave him the name Telari-o-lin, meaning “not divided,” an expression his contemporaries interpreted as “the last pure-blooded Huron.”

It was in this context that the painter Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895) invited Vincent to pose, at the age of twenty-three, for a portrait that perpetuated the myth of the vanishing and primitive Indigenous figure. Nevertheless, the work was a pivotal moment in Vincent’s life because it introduced him to the practice of painting. “He thus became the first Huron to adopt a pictorial medium rooted in Western tradition—easel painting—and developed a style that blends academic tradition with some technical imperfections.” Vincent is particularly noted for his self-portraiture. His composition Zacharie Vincent et son fils Cyprien (Zacharie Vincent and His Son Cyprien), affirms that contrary to the stereotypes of the time, his lineage was alive and thriving.

By becoming his own model, Vincent was able to craft an image aligned with his Wendat culture, conveyed through an identity-driven pictorial narrative in which every detail carries symbolic significance. This is evident in the presence of his son Cyprien, a cultural heir who asserts his heritage through the bow and arrows he holds, as well as the large circular silver medal—an adornment that contemporary Wendat sculptor Ludovic Boney (b.1981) would reinterpret in the twenty-first century with his work Parure de traite (Trade Ornament), 2021. These large medallions were given by the British Crown to Wendat allies, who decorated and repurposed them as proudly worn ornaments.

In Vincent’s later portraits, such as Autoportrait (Self-Portrait), c.1875–78, every adornment—pipe, axe, bow and arrows, wampum, medallion, bracelet, armband, Queen Victoria medal, feathered headdress, tricolour cockade, and Maltese cross—embodies the past and present of the Wendat chief’s history. These elements symbolize the resilience of his nation in the face of colonial authorities, as well as the miscegenation resulting from the Wendat community’s efforts to adapt and acculturate to settler society. For Vincent, self-portraiture “legitimates his social standing and differentiates him from the anonymous traditional artisan, allowing him to be recognized as an artist whose work is defined not only by technical skill but also by intellectual struggle.” Through self-portraiture, Vincent asserted himself as a professional artist within a community that was primarily acknowledged for its artisanship.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements