This chapter examines the influence exerted by the French Catholic Church in the establishment of cultural hubs in Quebec City during the French and British colonial regimes. It also explores the sweeping secularization movement that transformed Quebec society in the 1960s, without diminishing the importance the capital places on its treasures of sacred art and traditional culture. Quebec City continues to captivate the world through the institutions that have preserved these riches—a founding college, groundbreaking museums, and a pioneering school. At the same time, events on the international contemporary art scene and an innovative and inclusive network of artist-run centres bring the past and the present together in the city.

1635: The Collège des Jésuites

For more than a century, the Collège des Jésuites, also known as the Collège de Québec, served as a hub of learning and culture, becoming the first institution dedicated to cultural pursuits in the capital during the early days of the colony. French missionaries from the Jesuit Order established their base in New France as early as 1625, with an initial mandate of evangelizing the Indigenous communities and promoting the Catholic religion. Through missions established across the territory, the Jesuits exerted their influence among Indigenous Peoples from the two main linguistic families in Quebec City: Iroquoian and Algonquian. For nearly fifty years, they documented their endeavours in a collection of annual reports known as The Jesuit Relations. In 1635, they founded a classical college in Quebec City’s Upper Town to educate young boys, both Indigenous and settler.

The Collège des Jésuites offered courses modelled on the curriculum of colleges in France, including studies in the humanities and in sciences such as astronomy, cartography, and hydrography. Missionary teachers encouraged literary and dramatic performances during official receptions. Works by classical authors were read and performed, including Pierre Corneille’s Héraclius in 1651 and Le Cid in 1652, and Jean Racine’s Mithridate in 1694. Even the art of pyrotechnics was practised at the college, leading to spectacular displays that lit up the skies over Quebec City as early as 1637, notably during celebrations for the feast of Saint Joseph, patron saint of New France.

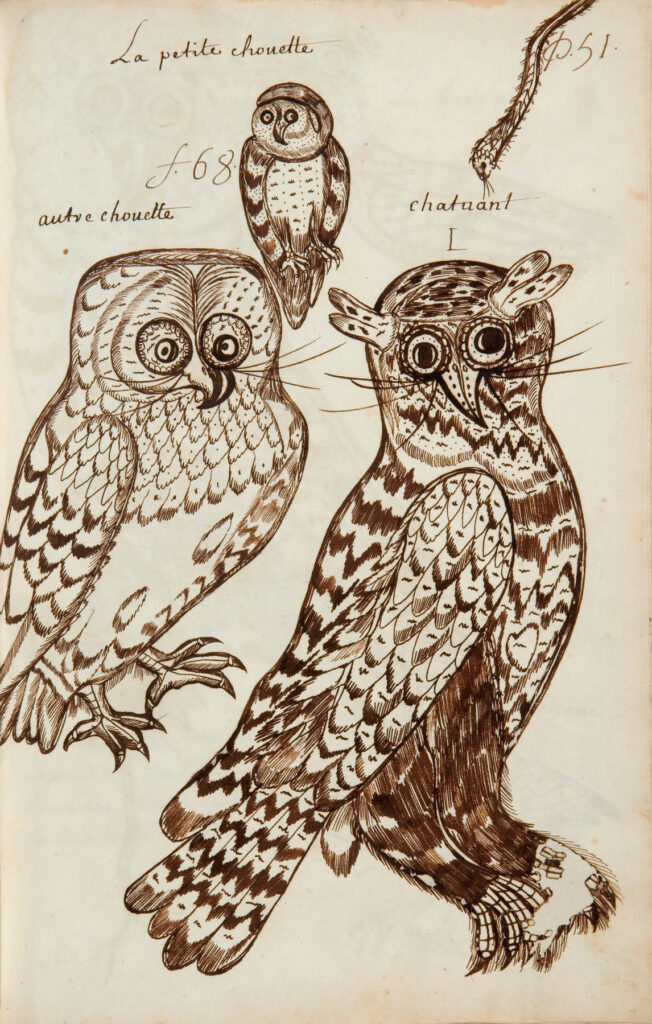

In the realm of visual arts, the college did not focus on providing formal training to its young recruits. But the Jesuits included among their ranks a few missionary painters, such as Jean Pierron (1631–1700) and Claude Chauchetière (1645–1709), who used drawing as a tool for religious conversion. Another missionary, Louis Nicolas (1634–post-1700), was less concerned with evangelization and instead devoted himself to documenting the flora and fauna of New France. His Codex Canadensis, which chronicles the natural history of the territory, is a one-of-a-kind work in an era when religious art dominated.

The Collège des Jésuites got its start in 1635 in the presbytery of the Notre-Dame-de-la-Recouvrance chapel, before moving in 1647 to a more permanent site (now the location of the Quebec City Hall). The new building, designed to reflect the college’s scholarly ambitions, was constructed in the monastery style, with wings arranged around a central courtyard. It housed a library containing several thousand volumes, making it the richest and most significant in New France. A church was added to the complex in 1666. To mark its inauguration and as a testament to the Jesuits’ evangelizing mission, the Wendat Nation presented the congregation with the painting La France apportant la foi aux Hurons de Nouvelle-France (France Bringing Faith to the Hurons of New France), c.1666, one of the most renowned pieces of seventeenth-century art.

The work, by an unknown artist, depicts “a [converted] Huron kneeling before Anne [of Austria], the mother of Louis XIV, and presenting a framed painting of the so-called extended Holy Family…. A French ship is docked in the bay in the background, surrounded by two small chapels and some highly conventional landscape.” The composition features a mise en abyme, a painting within a painting; it underscores the didactic intent behind the conversion strategies of the era, which aimed to make spiritual realities visible through art. This propagandistic painting highlights the noble aspirations of the French in the colony, emphasizing their mission to convert souls and welcome Indigenous Peoples into the greater Christian family.

The work, however, avoids depicting the less noble yet dominant commercial motivations behind colonization, which are prominently featured in Les castors du roi (The King’s Beavers), 2011, a painting by the Cree artist Kent Monkman (b.1965). He draws on La France apportant la foi aux Hurons de Nouvelle-France as one of his sources, reimagining the deceased beavers as cherubs and other saintly figures inhabiting the heavens of the seventeenth-century composition.

The Collège des Jésuites contributed to the education of Québécois and Canadian elites for 150 years. In 1776, the institution permanently closed its doors following the departure of several Jesuits and the prohibition on recruiting new members in Canada after the British Conquest.

1817–20: The Desjardins Collection

One of the most pivotal events in the development of art in Quebec City was the arrival, in 1817 and 1820, of 180 religious paintings by European masters of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In Canada—where there were at the time no academies or fine arts schools, and where aspiring painters received their training through private lessons or workshops—this collection provided an unprecedented opportunity to study and copy exceptional works. Originally created to adorn the churches of Paris, these paintings escaped looting during the French Revolution (1789–99). They eventually came into the possession of two brothers who lent their name to the collection: Abbés Philippe-Jean-Louis (1753–1833) and Louis-Joseph (1766–1848) Desjardins.

The older brother fled to Canada in 1793 to escape the turmoil of the French Revolution. He noticed the lack of religious imagery in the parishes of Lower Canada and acquired the works after he returned to Paris in 1802, acting as a merchant with the intent to resell them, as highlighted by the art historian Laurier Lacroix. The younger brother served as chaplain to the Augustinian nuns at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. He oversaw the delivery of the works—a first shipment of 120 paintings in 1817, followed by a second shipment of 60 in 1820—while also managing their restoration, display, and sale. The Desjardins Collection includes several compositions by Simon Vouet (1590–1649), a central figure of French Baroque painting, as well as a selection of eighteenth-century church paintings by prominent Parisian artists and a few secular works from the Flemish and Spanish schools.

This collection of sacred art inspired a generation of local painters, including Joseph Légaré (1795–1855), Jean-Baptiste Roy-Audy (1778–1846), Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895), and Théophile Hamel (1817–1870), who actively participated in the restoration of the works while honing their painting skills through copying. In the early 1820s, Légaré taught himself to paint partly by copying works from the Desjardins Collection; he acquired about thirty paintings for his personal collection.

Louis-Joseph Desjardins was also a significant patron of the arts, financing travel and training in Europe for Plamondon and Hamel through subscriptions he collected from other clergy members and friends. Because of the Desjardins brothers and the collection they curated, local painters gained practical training and the opportunity to pursue careers that would fulfill commissions from parishes and religious communities, which were rapidly expanding during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Quebec City artists are believed to have shipped more than 120 copies of paintings from the Desjardins Collection to parishes across French America. This body of works contributed to the emergence of Canadian history painting, as well as the practice of art collecting in the country. It also played a key role in the establishment of the city’s first galleries and museum, thanks to the exceptional journey of collector Joseph Légaré. In 2017, to mark the bicentennial of the arrival of the first shipment of Desjardins works, the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, in partnership with the Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes in France, presented the exhibition Le fabuleux destin des tableaux des abbés Desjardins (The Fabulous Destiny of the Paintings of the Abbés Desjardins).

1824: The Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (LHSQ)

The Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (LHSQ), the oldest English-speaking learned society in Canada, was founded in 1824 under the auspices of George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie (1770–1838), at Château Saint-Louis in Quebec City. In the nineteenth century, the capital had no dedicated visual arts societies equivalent to Toronto’s Society of Artists & Amateurs (1834) or the Montreal Society of Artists (1846), which later became the Art Association of Montreal (1860). Instead, literary societies took on a cultural role in Quebec City, much like Mechanics’ Institutes in England or reading cabinets elsewhere in Europe. They organized a wide range of activities, including discussion and reading sessions, lectures, and literary competitions, and they also created libraries and museums. These societies provided an unprecedented avenue for artists to professionalize their practice at a time when there were few opportunities for them to do so.

Since meetings at the LHSQ were conducted in English—the primary language for its regular publications and lectures—the society did little to attract the francophone segment of the population. As a result, the Société pour l’encouragement des sciences et des arts en Canada was established in 1827, though it quickly merged with the LHSQ in 1829. The francophone society aimed to nurture emerging talent from a French Canadian patriotic perspective and awarded annual medals in various categories. Painting was included under the literary class, provided the composition and drawing were the original invention of the artist. The painter Joseph Légaré received a medal in 1828 for his history painting Le massacre des Hurons par les Iroquois (The Massacre of the Hurons by the Iroquois), 1827–28. A decade later, Antoine Plamondon was similarly recognized for his portrait Le dernier Huron (Zacharie Vincent) (The Last of the Hurons [Zacharie Vincent]), 1838.

The LHSQ was initially established as an archive promoting research and higher education. In 1866, the society expanded by acquiring the collections of Quebec City’s first bilingual public library, founded in 1779. Today, the LHSQ’s English-language library contains more than 28,000 volumes. Over the twentieth century, the society evolved to operate more like a library, but it remains active and celebrated its two hundredth anniversary in 2024. Its heritage-oriented mission is to preserve historical documents from the colony and make them available to the English- and French-speaking public.

Since 1868, the LHSQ has been housed in the Morrin College building in Old Quebec. Originally constructed between 1808 and 1811, based on plans for a prison by the architect François Baillairgé (1759–1830), the building is one of the finest examples of the neo-Palladian style that dominated English colonial institutional architecture in Quebec City. The symmetry of the structure, the ornamental details, the restrained decoration, the tripartite composition of the facade, and the pediment and pilasters accentuating the central entrance all reflect the neoclassical style that Baillairgé adapted to revitalize the city’s architecture. Since 2011, the LHSQ has operated under the name Morrin Cultural Centre. It remains an important cultural pillar, promoting the heritage and history of the city’s anglophone community and fostering cultural exchanges with the francophone population.

1875: The Pinacothèque at Université Laval

In 1874, the Séminaire de Québec acquired the art collection of the painter Joseph Légaré. This collection, which included approximately 160 European and Canadian paintings, became the foundation of the first permanent art museum in the city—the Pinacothèque at Université Laval, inaugurated in 1875.

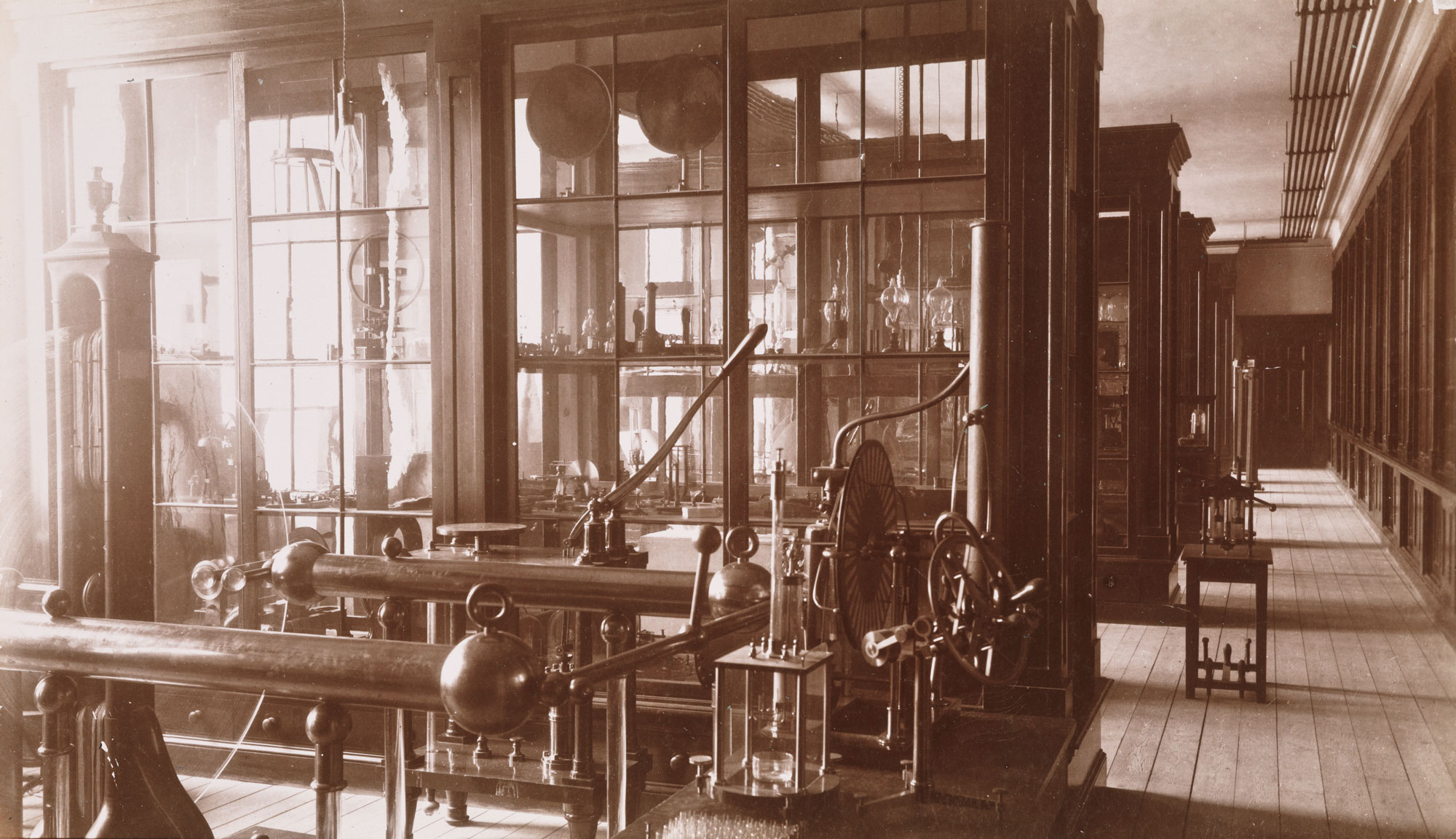

The Séminaire de Québec primarily held scientific and social collections; these were made accessible to the public starting in 1806 in cabinets or display areas then referred to as “museums.” The photographer Jules-Ernest Livernois (1851–1933) was among the first in the capital to capture these exhibition spaces. When Université Laval was founded by the Séminaire in 1852, the identity of these collections was strengthened because they became “university collections” with encyclopedic and educational purposes. Throughout the twentieth century, the institution’s fine arts collection grew significantly through various donations and bequests from professors, as well as through the continued collecting efforts of priests, who acquired paintings and prints during their travels abroad.

The Pinacothèque gained prestige because of the European origin of its collections. Among its highlights were the grand church paintings that shaped an entire generation of artists in Quebec City. This selection reflected the preferences of priests and their circles and focused on Counter-Reformation religious art, biblical themes, and saintly iconography. One notable work, Saint Jérôme entendant la trompette du Jugement dernier (Saint Jerome Hearing the Trumpet of the Last Judgment), 1717, by the French artist Pierre Dulin (1669–1748), displays the expressiveness, movement, and drama of Baroque painting—a favoured style for sacred art in Europe and later in Quebec City during the eighteenth century. Before it was acquired by the Séminaire, the painting was a centrepiece in Légaré’s collection. Légaré is thought to have participated in its restoration, as the painting arrived in Quebec City in poor condition. After restoring it, he produced two copies. Another significant piece in the collection, Le repos de la Sainte Famille durant la Fuite en Égypte (The Holy Family Rest on the Flight into Egypt), c.1750, attributed to Jean Restout (1692–1768), hangs on the reredos of the high altar in the Séminaire’s outdoor chapel. Its theme reflects devotion to the Holy Family, a tradition established in New France by its first bishop, François de Laval (1623–1708).

Landscape and genre scenes were also popular, enriching the collection with works such as La gourmandise (Gluttony), c.1642, attributed to the Flemish painter Jacques de l’Ange (active from 1631 to 1642). De l’Ange was a painter of the Northern European school and was influenced by the Italian artist Caravaggio (1571–1610), as seen in his use of an artificial radiant light source to create a dramatic chiaroscuro effect. Acquired by Légaré around 1838, the allegory of gluttony, depicted as a young man caught in a state of drunkenness, is part of a set of five Flemish paintings dedicated to the seven deadly sins.

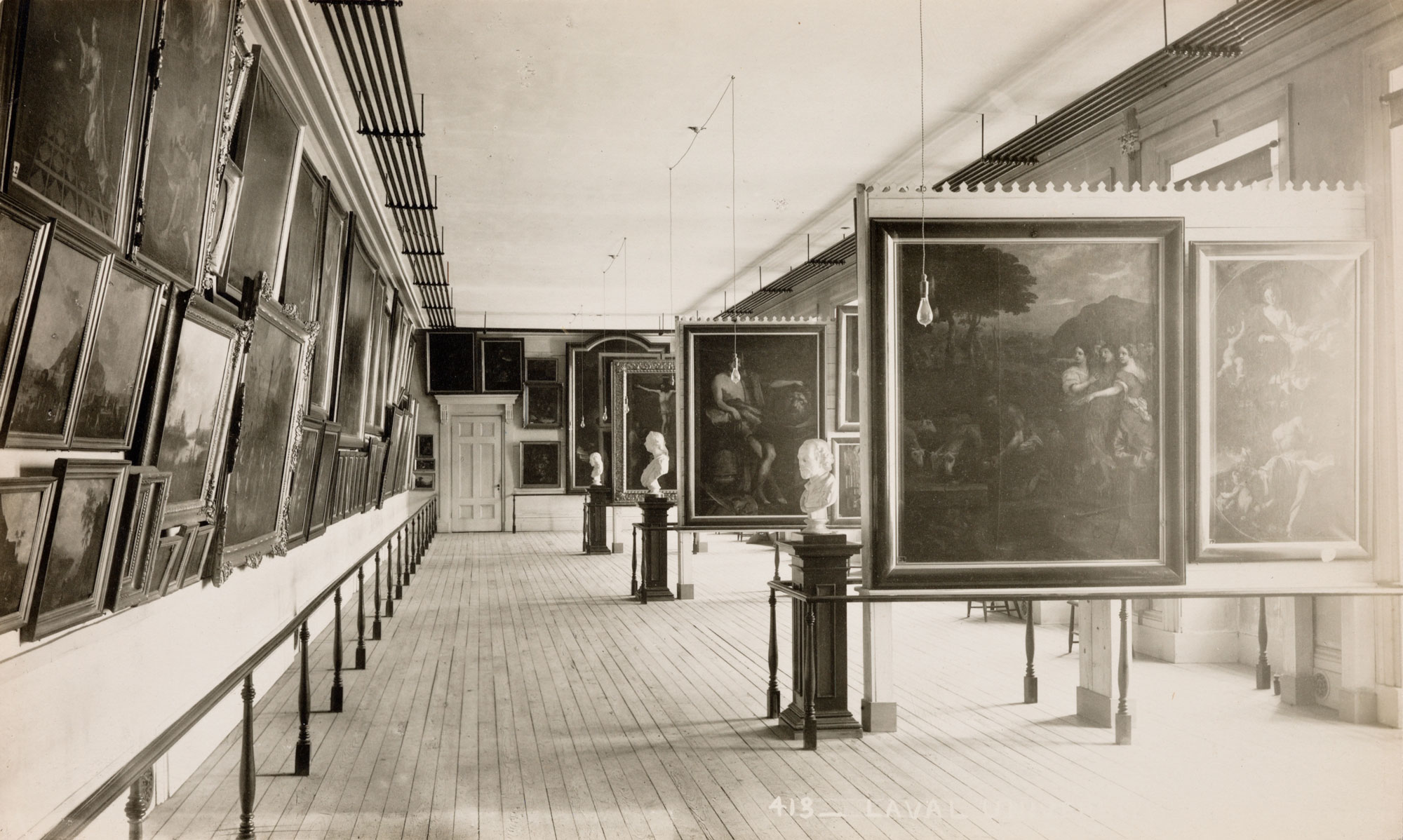

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Pinacothèque reached the height of its prestige, with the university planning to transform it into a national museum—a true “Canadian Louvre”—based on the quality of its European collection. The arrangement of paintings on the museum’s walls mirrored the style of major European salons, with frames hung edge to edge and minimal spacing to maximize display capacity. In 1907, the Pinacothèque was renamed the Musée de peintures. The collections were fully inventoried and acquisitions continued, but the national museum project never came to fruition. By the early 1960s, the Musée de peintures had been renamed the Musée du Séminaire. The fine arts collection—comprising paintings, sculptures, silverwork, and works on paper—was made more accessible than it had been during the Pinacothèque era. But it was not until the 1940s that local and broader Canadian paintings, particularly works by Légaré and Antoine Plamondon, moved from the university’s corridors and rooms to the museum’s walls.

In 1995, the provincial government recognized the unique value of the Séminaire’s collections—including its ethnographic and scientific artifacts, along with its archives and a collection of rare and ancient books—and entrusted this entire national heritage to the Musée de la civilisation in Quebec City.

1922: The École des beaux-arts de Québec

The École des beaux-arts de Québec (ÉBAQ), the first public art school in Canada, opened its doors on October 7, 1922, in the Faubourg Saint-Jean building, which for the previous forty years had housed the School of Arts and Crafts, an institution that focused on vocational training in trades such as drawing for the plumbing, shoemaking, and mechanics industries. The driving force behind the creation of the ÉBAQ was Louis-Athanase David (1882–1953), a provincial government minister who also spearheaded the founding of the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, which opened in 1923. After the First World War, David envisioned both schools aligning their curricula with the fine arts education model in France. They would develop courses in the classical academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures and copies of engravings by Old Masters. David believed that through these schools, the province could reclaim its French cultural identity and spread its influence across borders.

The close cultural relationship between France and Quebec City was evident at the ÉBAQ in various ways, including through its inaugural director, Jean Bailleul (1878–1949), and its first cohort of teachers—all of whom were graduates of French fine arts schools. France was also the destination for the most talented students: from the first graduating class in 1926, Omer Parent (1907–2000) and Alfred Pellan (1906–1988) received scholarships to study in Paris.

At the ÉBAQ, instruction was offered in architecture, drawing, painting, sculpture, decorative arts, engraving, and art history. Over the years, additional subjects were introduced, including stained glass, tapestry, ceramics, graphic arts, and photography. The school’s mission was to disseminate knowledge of art according to the academic standards established in Europe. But the nationalist ideology behind its creation also called for the development of distinctly “Canadian” art. From its early years under Bailleul’s leadership, the school promoted local arts by emphasizing the use of regional materials, such as clay and ore, in the teaching of pottery and wrought ironwork.

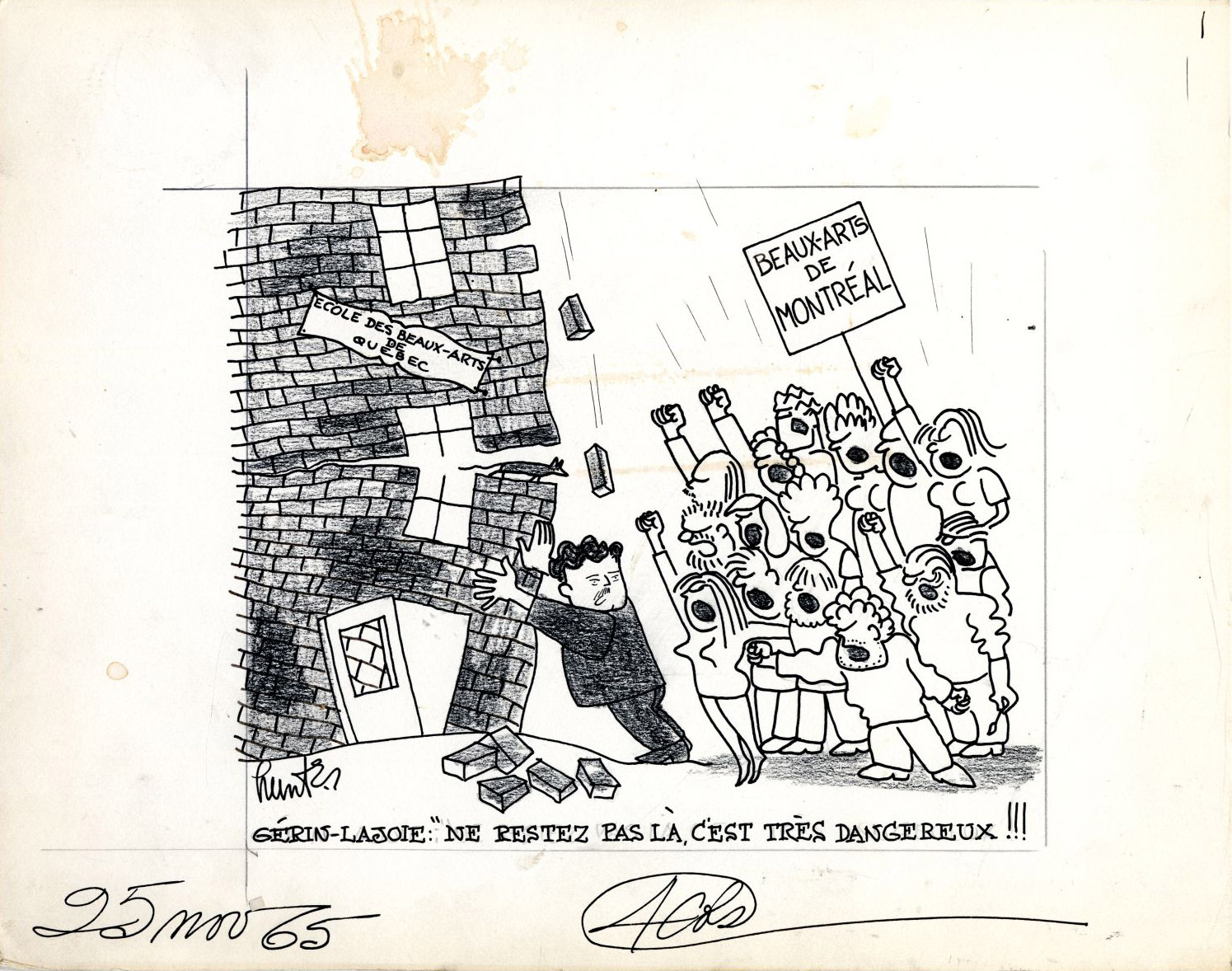

In the 1940s, the ÉBAQ did not experience an explosive anti-academic, anti-clerical, and anti-nationalist crisis like the one that culminated in the dismissal of Charles Maillard (1887–1973) as director of the École des beaux-arts de Montréal in 1945. Maillard had dominated the province’s artistic scene since the 1920s, but his positions, deemed outdated, led to his downfall at the hands of progressive advocates such as Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and Pellan. In the capital, however, more moderate professors like Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–1990) and Parent pursued progressive figurative art and encouraged greater artistic freedom among their students while fostering authentic expression. Through caricatures, paintings, and drawings, they sarcastically highlighted their deplorable working conditions.

One such caricature—Gérin-Lajoie : « Ne restez pas là, c’est très dangereux!!! » (Gérin-Lajoie: “Don’t stay there, it’s very dangerous!!!”), November 25, 1965, by Raoul Hunter (1926–2018)—condemned the ruinous state of the school. At the time, the provincial minister of education, Paul Gérin-Lajoie, had recommended avoiding the building entirely. Meanwhile, students from the École des beaux-arts de Montréal marched in solidarity with their counterparts in Quebec City, advocating for the school’s renovation. Soon after, the long-awaited reforms materialized, and the ÉBAQ was modernized. But it ceased operations on August 30, 1970, when Université Laval took over its role with the creation of its own school of art.

1933: The Musée de la province de Québec

In 1922, the Quebec government passed the Provincial Museums Act, adopted expressly to realize the national museum project envisioned by Provincial Secretary Louis-Athanase David as part of his ambitious cultural policy, which prioritized education and heritage preservation. The act “established the mandate to construct museums in Québec and Montréal,” but owing to a lack of financial resources, only the Quebec City museum was built. In the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash and throughout the Great Depression (1929–39), the environment was highly unfavourable to arts and culture, making the creation of the Musée de la province (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) in 1933 all the more remarkable.

The mandate of the province’s first national museum, as defined in the 1922 law, was to “serve the study of history, science, and the fine arts.” Initially, the Musée de la province housed three institutions reflecting these areas: the Archives du Québec, a natural history museum, and a fine arts gallery. The origins of its art collection date back to 1920, when the government authorized the purchase of contemporary works to form the nucleus of the future national collection. Among the initial acquisitions was Le pont de glace à Québec (The Ice Bridge in Quebec), 1920, by the Montreal artist Clarence Gagnon (1881–1942). When the museum opened in 1933, it had about eight hundred pieces in its collection; today, it has more than forty thousand.

It was not until the 1950s that the institution decisively shifted its focus to the visual arts, emphasizing art history with the goal of “finding a place in this history for French-Canadian art.” This new direction, which became exclusive by the 1960s, was spearheaded by the art historian Gérard Morisset (1898–1970), who was then the museum’s curator. In 1963, the Musée de la province was renamed the Musée du Québec, marking a turning point. “From that time, from quiet revolutions to bold aspirations, from unexpected stagnations to concerted spasms, the Musée du Québec became the national museum of French Canada.” In 1984, its status as a dedicated art museum was formalized when it became a state corporation managed by a board of directors. Finally, in 2002, the museum complex was renamed the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ) to reflect its renewed mission: showcasing Quebec art from its origins to the present day.

The museum has a strong collection of historical art, while its conservation and leadership teams demonstrate a keen sensitivity to modern and contemporary art. Among its flagship pieces are Coq licorne (Unicorn Rooster), 1952, by Jean-Philippe Dallaire (1916–1965); L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg (Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg), 1992, by Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002); abstract works by Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001) and Marcel Jean (b.1937), such as Jean’s No 1115, de la suite Les grâces (No. 1115, from the series The Graces), 2003, as well as Richard Mill (b.1949), including Sans titre (M-1351) (Untitled [M-1351]), 1989; sculptures by Paul Lacroix (1929–2014)—such as Pied (Foot), 1991—and Charles Daudelin (1920–2001); installations by BGL (active from 1996 to 2021); and tableaux vivants by Claudie Gagnon (b.1964). The museum also houses the impressive Brosseau Collection of Inuit art. In 1945, the creation of the Concours artistiques de la province made it easier to acquire prize-winning works for the museum’s collection until 1970. From 1976 to 1991, the Galerie du Musée du Québec operated as an extension dedicated to contemporary art, while the Prêt d’œuvres d’art collection, established in 1982 and still active today, is part of an art rental program open to government and corporate clients, making art more accessible to the public.

The museum is housed in the Gérard-Morisset Pavilion, built between 1927 and 1931 in the Beaux-Arts style, which is characterized by classical and austere French architectural elements. The pavilion features a monumental entrance with broad colonnades topped by a sculpted pediment. Erected in the middle of the Battlefields Park, on the Plains of Abraham, the building overlooks the St. Lawrence River. Between 1988 and 1991, the museum expanded to include the old Plains of Abraham prison, designed in 1861 by the architect Charles Baillairgé (1826–1906), the last descendant of Quebec City’s renowned Baillairgé dynasty. (Baillairgé also contributed to the design of the Dufferin Terrace and the main building of Université Laval.) The museum complex was further enhanced by the addition of the Pierre Lassonde Pavilion in 2016, and the new Riopelle Space is slated to open in 2026.

1940: The Alfred Pellan Exhibition

On June 12, 1940, the exhibition Alfred Pellan opened at the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec), an event that came to be regarded as a symbolic rupture between traditional and contemporary art. The exhibition was intended to celebrate the innovative recent work of the young Québécois artist Alfred Pellan, who had been abruptly repatriated to Canada due to the German invasion of France, where he had been living and building his art career for the previous fourteen years. In Quebec City, the exhibition—which included pieces such as Les pensées (Pansies), c.1935–37, and Jeune fille au col blanc (Young Girl with White Collar), c.1934—was a watershed moment in the emergence of modern art in the city and the province.

From 1922 to 1926, Pellan trained at the École des beaux-arts de Québec before receiving the province’s first scholarship to continue his studies in France until 1939. During this extended stay, he developed a striking artistic language characterized by vibrant colours and deconstructed forms, reflecting his deep engagement with European avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century, including Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, and abstraction. In 1935 alone, Pellan won first prize at the Salon de l’art mural in Paris, held his first solo exhibition in a small space at the Académie Ranson, and briefly joined the group of emerging artists known as Forces nouvelles (founded that year by the French art critic and painter Henri Héraut [1894–1981]). In 1939, Pellan was invited to participate in the exhibition Paris Painters Today in Washington, where his work was shown alongside that of renowned École de Paris masters, including Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), André Derain (1880–1954), Marie Laurencin (1883–1956), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

A few years earlier, in 1936, Pellan had briefly returned to Quebec to apply for a teaching position at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal. But he was deemed too innovative by the school’s director, Charles Maillard, as well as hiring committee members Horatio Walker (1858–1938) and Clarence Gagnon. As Gagnon bluntly put it, “You are modern, you are doomed.” The modernist ideas embodied in Pellan’s provocative works, such as Peintre au paysage (Painter in Landscape), c.1935, were poorly received within the traditional academic environment that prevailed in Montreal and Quebec City at the time. Four years later, in 1940, hundreds of Pellan’s works—including pieces like Jeune fille aux anémones (Girl with Anemones), c.1932, and Fleurs et dominos (Flowers and Dominoes), c.1940—crossed the Atlantic by ship for his solo exhibition at the Musée de la province de Quebec. It was the culmination of two decades of artistic practice. The exhibition challenged the conventions that had long defined local painting. Critics noted that it caused “a profound disruption in domestic conceptions of art,” as Pellan opened the conversation on modernism and its influences in the capital and beyond.

After its showing in Quebec City, a scaled-down version of the exhibition was presented at the Art Association of Montreal, creating a shockwave that inspired key figures of the Montreal art scene, including the painter Paul-Émile Borduas, who would soon begin work on the Refus global manifesto. Today, the Alfred Pellan exhibition is considered a landmark moment of art history, not unlike the Armory Show in New York in 1913. The event also paved the way for the high-profile 1945 visit of the French avant-garde painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955) to Quebec City and Montreal in 1945.

1972: The Artist-Run Centres

L’Atelier de Réalisations Graphiques, the first artist-run centre in Quebec City and one of the first in the province, was founded in 1972 by Marc Dugas (1945–2018), a printmaking professor at Université Laval’s École d’art. The goal was to break the isolation that young artists often face after completing their studies. At the same time, Dugas sought to share with his peers the heavy and expensive equipment required for printmaking production. These early forms of artist collectives were known as alternative galleries because they operated independently of traditional commercial galleries and museums.

“These community structures… were established to decentralize contemporary art into a map of diverse, unconventional, and unbounded spaces.” Since 1986, they have been identified as artist-run centres, a term that defines their very essence: management by a board of artist-members, emphasizing their autonomy and co-operative governance. These new art spaces also warmly welcome emerging artists who lack sufficient support from the network of private commercial galleries.

Operating alongside Quebec City’s robust commercial and institutional art systems, these artist-run centres form a dynamic, complex, and multifaceted network. The founding of La Chambre Blanche in 1978 marked a milestone in the emergence of alternative, non-institutional practices. Artists engaged in photography, video art, conceptual art, art actions (happenings, performances, and manoeuvres), ephemeral art, and site-specific art, among others. Some members of La Chambre Blanche later split off to advocate for a more activist and sociological approach; they founded the magazine Inter, art actuel in 1978 and Le Lieu, a contemporary art centre, in 1982. VU, a centre dedicated to photography, was created in 1981, and the following year, Obscure, a multidisciplinary co-operative focusing on new media and digital art, was set up and operated until 1996. In 1985, young emerging artists founded L’Œil de Poisson, which initially focused on photography but soon embraced all visual arts, fostering connections between different practices. In 2000, L’Œil de Poisson created Manif d’art, the prestigious Quebec City biennial. These kinds of collective international events highlight the vitality of the capital’s network of artist-run centres and their significant role in the global art scene.

The network of artist-run centres took root in Saint-Roch, a once-prosperous neighbourhood that had been in decline since the 1970s. The centres, like the artists themselves, found affordable spaces to rent while they worked to establish themselves. Over time, this network transformed Saint-Roch into an increasingly vibrant creative hub: the artist collectives shifted the cultural and commercial focus from the institutional and commercial axis of the Upper Town to the alternative, nonconformist Lower Town. Their influence was pivotal to the success of Mayor Jean-Paul L’Allier’s revitalization project for the neighbourhood in the 1990s and 2000s.

Against this backdrop, the Méduse cultural centre emerged in 1993 as a model for combining the production and dissemination of art with a supra-co-operative management approach. At Méduse, each participating organization maintains its autonomy while sharing resources and equipment within a co-operative framework. Located at the junction of Lower Town and Upper Town, at the top of côte d’Abraham, Méduse occupies nine interconnected and renovated buildings. It houses ten non-profit organizations specializing in media arts, visual arts, and multidisciplinary arts, including VU, Engramme (the successor to L’Atelier de Réalisations Graphiques), L’Œil de Poisson, and Manif d’art. The complex offers specialized production and distribution services and supports professional artist residencies at the local, national, and international levels. It also provides training and equipment and hosts artistic activities and special events.

In 2023, Ahkwayaonhkeh, the first Wendat artist-run centre in Quebec City, opened at Méduse, which is located on Nionwentsïo (“our magnificent territory” in Wendat), the ancestral land claimed by the Wendat Nation. The programming committee, comprising Frédérique Gros-Louis, Nicolas Renaud, and Guy Sioui Durand (b.1952), aims to foster the emergence of the next generation of Indigenous artists.

1988: The Musée de la civilisation (MCQ)

The Musée de la civilisation (MCQ) opened its doors in Quebec City in 1988. Established as a government corporation under the 1983 National Museums Act, the MCQ is a museum dedicated to society, housing ethnographic, bibliophilic, numismatic, archival, and artistic collections and preserving and showcasing more than 225,000 objects, including over 6,000 works of art from prestigious collections. In 1995, the MCQ received a significant addition to its collection when the provincial government entrusted the institution with the holdings of the Séminaire de Québec. These included the entirety of the archives, established by the priests in 1663, as well as many works of art, notably the Séminaire’s first acquisition: Le repos de la Sainte Famille durant la Fuite en Égypte (The Holy Family Rest on the Flight into Egypt), c.1750, attributed to the French painter Jean Restout (1692–1768). The holdings also consisted of liturgical artifacts such as the exceptional Parement d’autel de l’Adoration des bergers (Altar Frontal with The Adoration of the Shepherds), 1850, by the English artist Robert Clow Todd (c.1809–1866).

Thanks to the acquisition of this invaluable collection, which was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2007, the MCQ gained an international profile. The museum also stands out for its extensive collection of First Peoples art, comprising approximately eight thousand objects representing nearly one hundred cultures across North America, South America, and Oceania. This collection plays a crucial role in promoting the heritage and culture of Indigenous nations by highlighting their diversity and originality. The first acquisition dates back to 1959, when the art historian Gérard Morisset recommended the museum purchase a collection from the estate of Pierre-Albert Picard, who was a grand chief of the Wendat Nation. This collection has many significant pieces, including a chief’s headdress from the early nineteenth century and a variety of artisanal works, such as moccasins, frock coats, basketry, wampum, and more.

In the decades since, the museum’s collection has continued to grow, generating remarkable exhibitions such as Œil amérindien: Regard sur l’animal (The Amerindian Eye: A Look at the Animal), 1991, and Nous, les Premières Nations (We, the First Nations), 2009. In 2012, the MCQ updated its 1989 policy on Indigenous Peoples in light of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The museum had already committed, in 1992, to a major objective: promoting the self-determination of First Peoples and amplifying their voices in the creation of their histories. This commitment was reinforced by an institutional framework adopted in 2012. The permanent exhibition C’est notre histoire : Premières Nations et Inuit du XXIe siècle (This Is Our Story: First Nations and Inuit in the 21st Century)—and its accompanying publication, Voyage au cœur des collections de Premiers Peuples—received the Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Museums in 2014.

As it celebrated its thirtieth anniversary in 2018, the MCQ reaffirmed its friendship with the Wendat Nation by issuing a call for proposals to create an artwork for its grand hall. Les arches d’entente (The Arches of Understanding), 2020, by Ludovic Boney (b.1981) was unveiled on June 21, 2021, during National Indigenous Peoples Day. The arch motif evokes Wendat longhouses, while the shades of blue reference both the provincial flag and the waters of the St. Lawrence River at the museum’s doorstep.

The MCQ is housed in a remarkable building steeped in modernity and designed by the internationally renowned architect Moshe Safdie (b.1938), famous for creating Habitat 67 in Montreal and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. Safdie’s design for the museum artfully incorporates the surrounding historic architecture and includes the Maison Guillaume-Estèbe, an urban bourgeois residence built around 1752 and one of the few classical-style structures spared during the bombardments of the Battle of Quebec in 1759.

Safdie skillfully bridges past and present in his architecture, which flows seamlessly into the built fabric of Old Quebec. The MCQ’s tower evokes both a lighthouse and a church, fitting harmoniously into the historic Lower Town, once renowned for its port and commercial activities and now celebrated for its tourism. The museum is located near Place Royale, an iconic site marking the city’s colonial founding in 1608, for which it was entrusted with a special fund for enhancement and programming in 2021. Firmly rooted in its own time, the MCQ received the 2023 Tourism Industry Award of the Year from the Quebec City Chamber of Commerce.

1989: Territoires d’artistes, paysages verticaux (Artists’ Territories, Vertical Landscapes)

The outdoor exhibition Territoires d’artistes, paysages verticaux (Artists’ Territories, Vertical Landscapes), which was organized by the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec) and ran from June 15 to October 1, 1989, was a unique event in the capital’s art history. When the museum had to close temporarily for an expansion, the curatorial team saw an extraordinary opportunity to promote contemporary and current art across the city. Louise Déry, curator of contemporary art, invited several visual, literary, and sound artists from both Canada and abroad to produce works for various sites in Old Quebec and the Plains of Abraham, inspired by the verticality of Quebec City’s natural landscape.

The city itself served as the common material for these artists: “The territory will become a canvas, a workshop, a gallery, a page, a darkroom, or a sound studio.” With its protective walls, steeples, chimneys, and staircases, not to mention a topography defined by a significant rise from the river, the city invited visitors to “follow a vertical trajectory.” During the summer of 1989, sculptures and installations briefly became landmarks throughout the urban landscape.

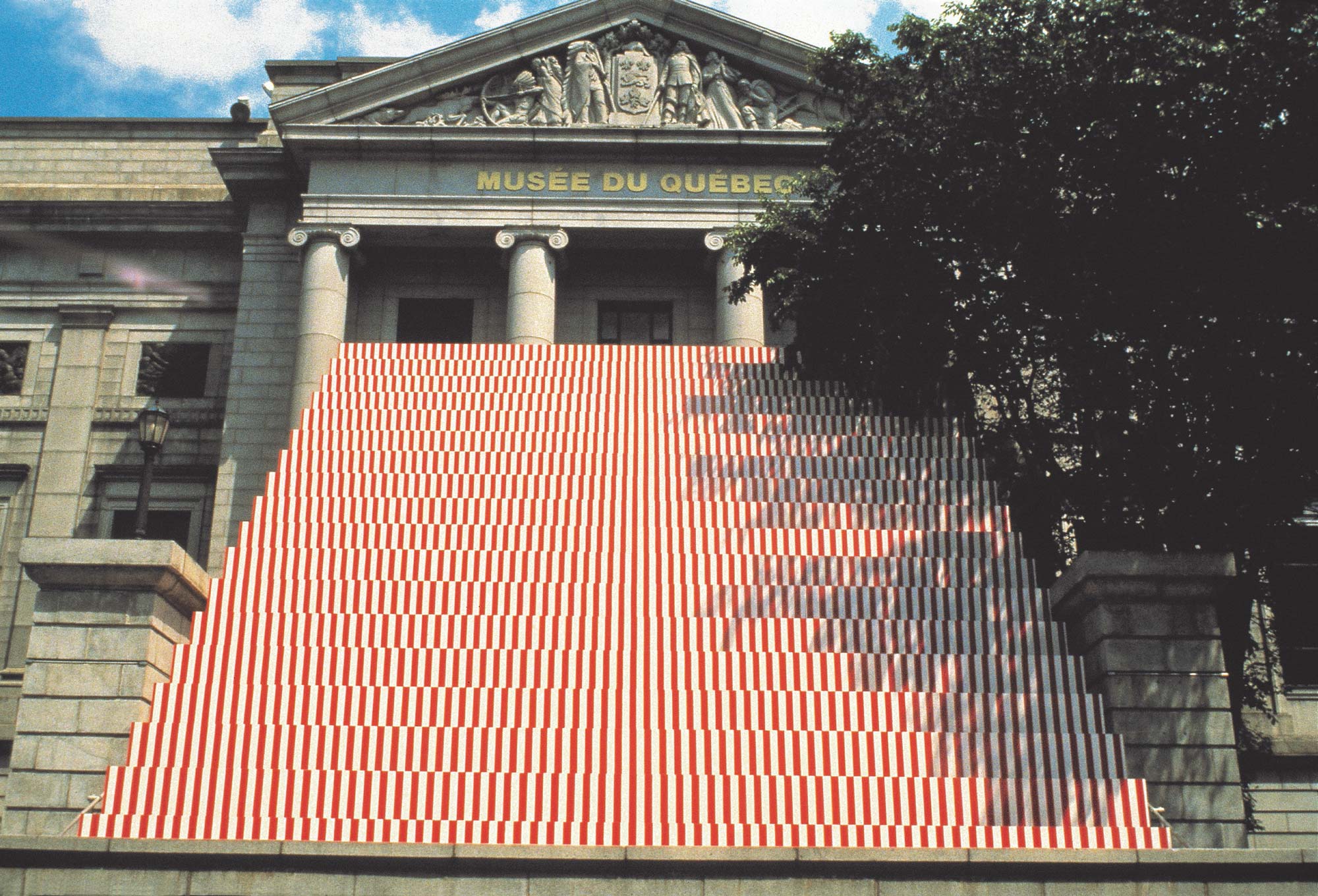

One of the most striking exhibited works, L’escalier remonté (The Reimagined Staircase), 1989, by the French artist Daniel Buren (b.1938), covered the flight of steps at the main entrance of the museum, which was closed to the public. This conceptual and minimal piece featured Buren’s signature red and white stripes, creating a stark contrast to the austere colonnaded facade of the building. The Quebec City artist Jocelyn Gasse (b.1949) drew his inspiration from the city’s very foundation, using the vertical face of Cap Diamant as the basis for a site-specific work. Another local artist, Danielle April (b.1949), designed a painted sculpture that referenced the city’s church steeples. The Montreal artist Melvin Charney (1935–2012), best known for exploring the relationship between nature and architecture, contributed sculptures resembling wooden flags animated by the prevailing wind.

Territoires d’artistes, paysages verticaux was accompanied by an exhibition catalogue and a compact disc. The CD evokes the soundscape of Quebec City with music composed by Toronto artist Michael Snow (1928–2023), which was the subject of a performance in Youville Square. The poets Denise Désautels (b.1945) and Frédéric-Jacques Temple (1921–2020) and the photographer Angela Grauerholz (b.1952) produced works exclusively for the exhibition catalogue.

The 1989 exhibition embraced site-specific installation practices that had been explored in some alternative galleries about a decade earlier. Twenty-five years before EXMURO’s Passages insolites (Unusual Passages) exhibition, it anticipated the prominent role that the city’s cultural institutions would give to contemporary and current art, both local and international, and the ways that art would be integrated into urban spaces.

2000: Manif d’art—La Biennale de Québec

Manif d’art was established in 2000 under the name Manifestation internationale d’art de Québec (MIAQ). Its founder, Claude Bélanger (b.1961), then director of the artist-run centre L’Œil de Poisson, wanted to develop an internationally significant project to counter the exodus of young artists from Quebec City and showcase them on the national and international contemporary art stages. The project aimed to unite the various actors of the city’s cultural life—artists, artist-run centres, galleries, museums, and many others. Today, this contemporary art festival, the only one held in winter in North America, has matured into a key event on the cultural and tourist calendar of Quebec City.

Since its first edition, Manif d’art has offered exhibitions in galleries and artist-run centres, as well as in the streets of the city, with the participation and support of more than fifty cultural organizations. In 2013, the event adopted its current name, Manif d’art—La Biennale de Québec. Four years later, the festival secured a partnership with the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, which has since hosted the event’s main exhibitions in the Pierre Lassonde Pavilion, as well as offering gallery and outdoor programming.

In 2024, Manif d’art celebrated its eleventh edition with the exhibition Les forces du sommeil: Cohabitations des vivants (The Strength of Sleep: The Cohabitations of All the Living), featuring some thirty indoor and outdoor exhibition venues throughout the capital. From February to April, the city pulsed to the creativity of more than one hundred artists exploring a wide range of expressive forms—film and video, sound art, printmaking, photography, ceramics and weaving, painting, sculpture, and installation. The curator of Manif d’art 11, Parisian Marie Muracciole, drew inspiration from Quebec’s long winter, a time of dormancy for both the earth and humans, while also being attuned to the many shades of awakening. The diverse artworks displayed delved into myth, fiction, and dreams.

Over the years, Manif d’art has also engaged in related activities, such as promoting mentorship, circulating works by Québécois artists abroad, and boosting the profile of local creators. The Young Curators program, supported by La Maison Simons and introduced during the ninth edition of Manif d’art to be a regular feature, offers smaller-scale exhibitions overseen by emerging curators.

In 2005 and 2006, Manif d’art helped promote exhibitions by the installation artist Jocelyne Alloucherie (b.1947) in three European cities. The organization has also showcased Québécois exhibitions at major international biennials, such as those in Liverpool (2008 and 2010), Guadalajara (2012), and Birmingham (2019). It also organized a 2015 visual arts exchange between artists from Quebec City and Nantes, France. Manif d’art has received several awards for its work, including a Grand prix du tourisme québécois for the Quebec City region in 2006 and the Prix Ville de Québec in 2005 and 2017 for contributions to arts and culture.

2008: Quebec City’s Four Hundredth Anniversary

The celebrations for Quebec City’s four hundredth anniversary marked the culmination of a years-long process that channelled the capital’s creative energies into a cultural festival organized around the theme of encounter. Quebec City is a site of many memorable and transformative encounters: between Europe and the Americas, between France and England, between Indigenous and colonial peoples, between past and present, and between artists and their audiences. The 2008 commemoration offered hundreds of unique events in a variety forms, engaging art and the historic sites that shape the city’s identity. These included open-air spaces such as public squares, parks, and waterfronts, as well as built spaces, like museums, churches, and art galleries.

The flurry of activities that took over the city began in the spring with the opening of the Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations in Wendake, near Quebec City. This innovative complex includes the Huron-Wendat Museum, which is the result of a project coordinated by the Wendat Nation and is rooted in the traditional alliance between Indigenous culture and tourism that has flourished since the early nineteenth century. There were also events to mark the twentieth and seventy-fifth anniversaries, respectively, of the Musée de la civilisation (MCQ) and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ). These milestones inspired a series of projects intertwining art and history across past and present. At the MNBAQ, the exhibition Québec: Une ville et ses artistes (Quebec: A City and Its Artists) highlighted the contributions of twenty-two significant Quebec City artists, from Frère Luc (1614–1685) to Edmund Alleyn (1931–2004).

This erudite exploration was complemented by the MNBAQ exhibition C’est arrivé près de chez vous : L’art actuel à Québec (It Happened in Your Neighbourhood: Contemporary Art in Quebec), which brought together works created over the previous fifteen years by around fifty artists from different generations, all influenced by the spirit and culture of the city. People were invited to immerse themselves in the vibrant creativity of the local art scene through a showcase of installations, tableaux vivants, experimental practices, sound creations, and video art. The installation Mandala Naya, de la série Le déclin bleu (Mandala Naya, from the Blue Decline Series), 2002, by Diane Landry (b.1958), used humble materials—plastic baskets and repurposed water bottles—controlled by an automated system to produce extraordinary shadow and light effects. The BGL collective produced Perdu dans la nature (La piscine) (Lost in Nature [The Pool]), 1998, an above-ground wooden pool that was described as a “scathing caricature of suburban aesthetics,” which brought fame to the trio.

At the heart of the celebrations was a tribute to Quebec City by the renowned multidisciplinary artist Robert Lepage (b.1957) and his production company, Ex Machina. The artist presented a dazzling multimedia work, Moulin à images (Image Mill), 2008–14, which showcased the evocative power of art and imagery as narrators of the city’s history. Lepage drew on previously unreleased archives to craft a visual narrative that blended cartography, drawing, engraving, painting, photography, and video—a synthesis of artistic languages that has become the hallmark of his practice. Four centuries of cultural history unfolded in a mega-projection displayed on an extraordinary canvas formed by the eighty-one grain silos in the Port of Quebec.

Moulin à images, the largest multimedia projection in history, gave profound meaning to the anniversary celebrations through the impressive historical panorama it portrayed. It was such a staggering popular success that the city extended its run, with some variations, until the summer of 2013.

2014: EXMURO’s Passages insolites (Unusual Passages)

The non-profit organization EXMURO was founded in 2007 by Vincent Roy, who serves as its co-executive director and artistic director. EXMURO stages and promotes multidisciplinary artistic projects in urban spaces, with the primary goal of displaying art outside traditional venues (hence its name, which means “beyond the walls”). EXMURO was inspired by major events such as the land art exhibition Territoires d’artistes, paysages verticaux (Artists’ Territories, Vertical Landscapes), 1989, which highlighted Quebec City’s enthusiasm for expressing art in urban spaces. In 2014, EXMURO launched the public art project with which it has been most closely associated: Passages insolites (Unusual Passages), 2014–23.

Passages insolites was an annual event that took place during the summer in Quebec City’s historic and tourist districts. Viewers would follow a preset route to discover artworks designed to challenge them to see the urban environment with fresh eyes. The goal was to surprise and delight the public with unexpected encounters between art and architecture, fostering a sense of wonder. Over the years, several works were preserved to create a collection that could be presented in other locations. For example, the piece Passage migratoire n° 2 (Migratory Passage No. 2) by Giorgia Volpe (b.1969) was featured in the 2017 edition of Passages insolites in Quebec City and later reimagined for a public exhibition in Örebro, Sweden, in 2022. Between 2014 and 2024, over two hundred artists of local, national, and international renown participated in Passages insolites.

The summer 2023 edition provided an opportunity to highlight Indigenous communities on the public art stage. On June 21, National Indigenous Peoples Day, Passages insolites was launched with a smudging ceremony, followed by traditional dances and songs led by a collective of Wendat women. The event took place at Place Royale, on the site of the first trading post in North America, where Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church now stands—a spot rich with historical significance for both colonizers and First Nations.

In this edition, EXMURO added the Passage intérieur (Interior Passage) project to the event. This new initiative featured exhibition spaces within the Maison Hazeur at Place Royale, a building that served as the residence of the prosperous fur trader François Hazeur in the eighteenth century. Four artists were invited to take over one of the house’s floors.

An installation by the French artist Baptiste Debombourg (b.1978), Nature radicale (Radical Nature), 2023, and a video by the Czech artist Daniel Pešta (b.1959), Chain, 2023, explored themes of destruction. The exhibition by the Opitciwan Atikamekw artist Eruoma Awashish (b.1980), Kakike Ickote (Feu éternel) (Kakike Ickote [Eternal Fire]), 2023, transformed the historic vaults—once used for commercial fur storage—into an animist sanctuary where ravens, bears, beavers, foxes, and moose lived side by side. Finally, the Wendake-born artist Ludovic Boney reflected on his community and the domestic spaces of the longhouse in his installation Rassemblement familial (Family Gathering), 2019.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements