Jules-Ernest Livernois (1851–1933)

Jules-Ernest Livernois, La Haute-Ville et l’hôtel du Parlement vus de l’Université Laval, Québec (Upper Town and the Parliament Building Seen from Université Laval, Quebec City), c.1890

Gelatin silver print, 12 x 21.5 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

A successful Quebec City businessman, Jules-Ernest Livernois dominated the field of photography in the last quarter of the nineteenth century through the abundance, diversity, and quality of his work. Despite competition from George William Ellisson (1827–c.1879) and Louis-Prudent Vallée (1837–1905)—two renowned masters of light who also operated studios on rue Saint-Jean in that era—Livernois enjoyed unparalleled commercial success with a broad clientele. He was celebrated for his portraiture, but like most practitioners of this new medium, Livernois left a distinctive mark on photography in Quebec City by “turning his lens to multiple subjects,” including events, landscapes, and urban views—such as the sweeping panorama La Haute-Ville et l’hôtel du Parlement vus de l’Université Laval, Québec (Upper Town and the Parliament Building Seen from Université Laval, Quebec City)—as well as genre scenes, photojournalism, industrial and architectural views, and more.

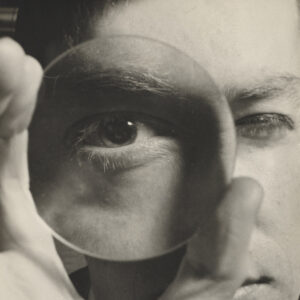

In 1874, Livernois took over the family photography business, founded twenty years earlier by his parents, Jules-Isaïe Livernois and Élise L’Heureux. Jules-Ernest was deeply “rooted in the ideology of industrial capitalism of his time,” according to the art historian Zoé Tousignant. This is evident, on the one hand, in photographs that capture the city’s industrial sites and activities, such as Une grue flottante de la Commission du havre de Québec avec des ancres et des chaînes (A Floating Crane of the Quebec Harbour Commission with Anchors and Chains), 1877. The balanced frontal view, emphasizing intricate details such as the links in the chains, seems to glorify the machine. On the other hand, Livernois’s capitalist outlook is reflected in the studio he established in 1889 on côte de la Fabrique. Equipped with state-of-the-art technology, the studio featured a posing room with scenic backdrops, a lavishly furnished reception salon in the Victorian style, darkrooms, retouching and assembly rooms, a boudoir for women to get ready, and a separate dressing room for men.

This era saw the advent of easier-to-use cameras, industrially produced dry plates, and more durable gelatin prints—technologies that revolutionized both the practice and the business of photography. Livernois worked with silver gelatin primarily for his outdoor shots, while the many portraits he produced in his studio were printed in the carte-de-visite format.

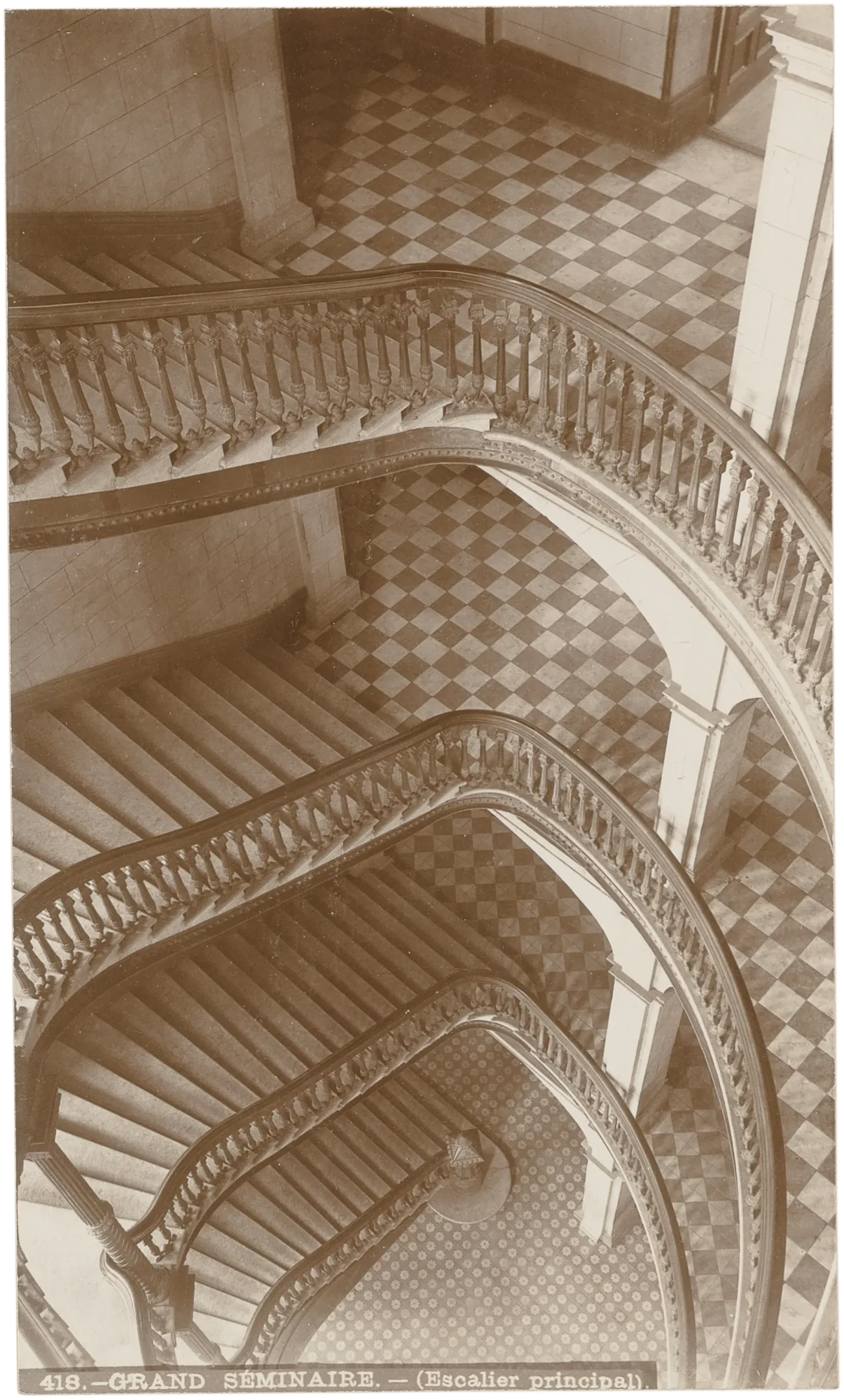

Livernois is also regarded as “the most artistic of photographers.” He departed from conventions and classical perspectives to create striking minimalist images that appear as fragments of the modern world. In this sense, he conveyed an early modernist vision, notably in his high-angle view of Le grand escalier du Grand Séminaire, Québec (The Grand Staircase of the Grand Séminaire, Quebec City), c.1895, which showcases the recurring geometric patterns of the architecture.

Interior views of other Quebec City religious institutions, such as Le dortoir des Augustines au monastère de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Québec (Dormitory of the Augustinian Sisters at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec Monastery), c.1925, with its amplified perspective, reveal Livernois’s artistic sensibility, which links him to early twentieth-century modernists like László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), whose radical low-angle geometric shots glorified machines and progress in the 1930s.

In 1898, Livernois transferred his business to his son Jules (1877–1952), who shared his father’s artistic sensibility. He was the last in the prominent family of photographers, whose studio remained active in Quebec City until 1974.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements