First Nations Creators of the Beads of Diplomacy

Once-known Wendat artist, wampum belt, 1678

Mercenaria mercenaria (quahog clam), sea snail, glass beads, leather, porcupine quills, plant fibres, 145 cm (length)

Chartres Cathedral, France

The earliest forms of art created in what is now Quebec City come from the ancestral cultural practices of Indigenous Peoples, including the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and, notably, the Wendat, who trace their lineage to these predecessors and used the territory as a transit point long before the arrival of Europeans. Their settlements along the banks of the St. Lawrence River in the Quebec City area and the National Capital Region have left clear material traces. Several sites—such as the low terrace of Place Royale—have been the focus of excavations and have proven to be teeming with history. Archaeologists have found arrowheads made of chert and quartz extracted from the cliff approximately five thousand years ago. Various artifacts, such as ceramic vessels, attest to the artisanal practices of the pre-contact period and provide insight into the evolution of these nomadic or semi-nomadic people toward a more settled way of life.

-

Mercenaria mercenaria (also known as the hard clam or northern quahog), 2016

Photograph by E.A. Lazo-Wasem

-

Once-known artist, The Two Dog Wampum, 1721–81

Shell: northern quahog (Mercenaria mercenaria), knobbed whelk (Busycon carica); hide: deer buckskin (Odocoileus virginianus); fibre; pigment: red ochre, with fringes: 20 x 0.5 x 238 cm, without fringes: 20 x 0.5 x 169.5 cm

McCord Stewart Museum, Montreal

With the arrival of colonization in the seventeenth century, Indigenous Peoples gained access to new materials and tools. White and purple shell beads, known as wampum, were already circulating as a medium of exchange, albeit in limited quantities due to the skill required to produce them. These delicate tubes—just three to five millimetres in diameter and up to one centimetre in length—were crafted from the hard shell of the quahog clam, which is white with a purple interior. Coastal Atlantic communities pierced the shells with holes and polished them to create wampum.

Starting around 1620, European metal drills became available, making it easier and more efficient to produce the tubular beads. As the art historian Jonathan Lainey notes, these beads became “an essential exchange good in the vast trade network that developed… during the fur trade period.” The new tools enabled the mass production of wampum beads, which were soon being created by the thousands.

These beads, assembled into necklaces or belts, formed impressive woven works of various sizes, composed of hundreds or even thousands of white and purple beads. These unique tones allowed the creation of an infinite variety of patterns—letters, figures, lines, geometric shapes, and more—rich with meaning. A drawing by the naval writer Bacqueville de La Potherie (1663–1736), published in his book Histoire de l’Amérique septentrionale in 1722 and devoted to New France, shows the difference between the wampum belt and the branch of wampum known as porcelain, the former being a more complex weave and the latter an assembly of beads on a single thread.

The Iroquoian nations of the central territory of North America assigned a major diplomatic role to these belts in relationships between Indigenous communities and with colonists. In New France, one of the “first detailed descriptions of the use of wampum in diplomatic meetings” comes from the writings of the Ursuline nun Marie de l’Incarnation (1599–1672). Wampums carried words and memory, documenting the speeches delivered: “They are the visual traces of an idea that can thus be ‘read.’” These symbolic creations were given a role to play in fostering socialization and reinforcing relationships. Between 1650 and 1750, a dozen votive wampums, which celebrated the Virgin Mary and other saints, were created by Indigenous Peoples living in religious missions in the Quebec region and presented to places of worship as offerings. The Huron of Lorette (now the Wendat of Wendake) crafted most of these belts. One was presented to the French cathedral of Notre-Dame de Chartres in 1678. It features elaborate Latin inscriptions—“VIRGINI PARITVRÆ VOTVM HVRONUM” (“Huron vow to the Virgin who is to give birth”)—reaffirming the community’s connection to the Catholic devotion to the Virgin Mary.

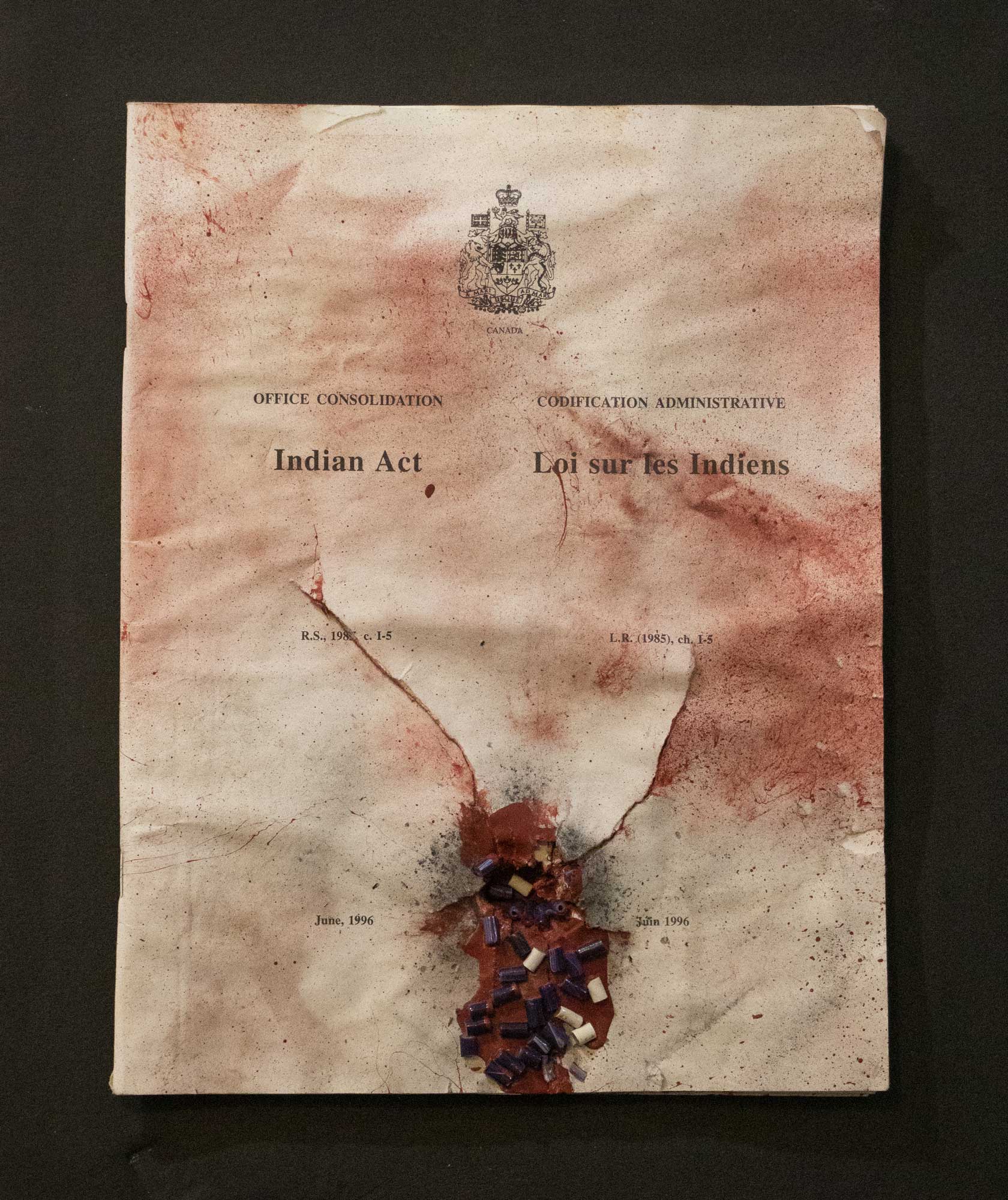

Wampums lost their political significance in the nineteenth century, a time of immense upheaval for Indigenous Peoples in Canada that culminated in the passage of the Indian Act in 1876. Belts became family heirlooms or collectors’ items and were often regarded by ethnologists of the period as “relics of a race destined to vanish,” as stated by Jonathan Lainey. In the twenty-first century, wampum beads regained their profound meaning and have been reimagined in contemporary Indigenous art. In 2009, the Wendat artist Teharihulen Michel Savard created the mixed-media work Réciprocité (Reciprocity), incorporating text from the Indian Act, which granted the Canadian government full authority over Indigenous Peoples and their lands. In this piece, Savard “executes” the controversial text by perforating it with a shotgun blast. From the hole—which is coated in red paint, symbolizing Indigenous identity—spill wampum beads, “once used in alliances and treaties violated by the Canadian state.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements