Théophile Hamel (1817–1870)

Théophile Hamel, Autoportrait au paysage (Self-Portrait in the Landscape), c.1841–43

Oil on canvas, 140 x 119.5 cm

Musée de la civilisation, Quebec City

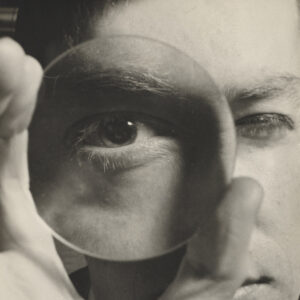

Théophile Hamel, Autoportrait dans l’atelier (Self-Portrait in the Studio), c.1849

Oil on canvas, 53.8 x 42 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

Théophile Hamel, the son of a farmer, was born on a plot of land near Quebec City in 1817 and rose through the ranks of society by practising portraiture. Displaying talent from a young age, he began an apprenticeship at sixteen with Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895), where he received European-style training focused on drawing and copying paintings from the Desjardins Collections. In 1840, after six years of instruction, Hamel opened his own studio. Around this time, he painted Autoportrait au paysage (Self-Portrait in the Landscape), in which he depicted himself as a serious draftsman working outdoors, dressed in a white smock and equipped with a mechanical pencil and sketchbook, against a natural background. The composition was designed to assure potential clients of his skills in drawing, landscape, and portraiture. But Hamel realized that, like his mentor Plamondon, he needed to refine his craft in Europe to fully secure their confidence.

From 1843 to 1846, Hamel lived primarily in Rome, with additional stays in Florence, Bologna, Venice, Paris, and Antwerp, funded by a substantial list of commissioned copies from Quebec City’s religious authorities. He became the first Canadian painter to travel to Italy and Flanders, venturing beyond France to refine his training. Upon his return to Quebec City, he created Autoportrait dans l’atelier (Self-Portrait in the Studio), which reveals a far more assured artist—almost heroic in the dramatic light streaming into his studio. Positioned before his easel, Hamel holds a palette and brush—the tools of his profession—and appears to have paused mid-action to meet the viewer’s gaze.

Hamel exhibited the same honesty and vigour in portraying members of the ruling elite who commissioned his work—be they bourgeois, ecclesiastic, or military; francophone or anglophone; Catholic or Protestant. These included figures such as the notary Archibald Campbell in 1847 and Madame Cyrice Têtu, the wife of a wealthy merchant, who posed with her son Amable in 1852. In these portraits, the background is dominated by velvet drapes with just a sliver of landscape peeking through. This focuses the viewer’s attention on the subjects—their expressions, gestures, and attributes, all of which attest to their social standing. The notary is shown at work, pen in hand, while the nurturing mother embraces her son, a reminder of Hamel’s reputation as “the portraitist par excellence of children.” Their social prestige is embodied in the painted effigies by Hamel, whose own social standing grew with each new commission he received.

Hamel’s rise as a portraitist reached a pinnacle in 1853, when the government commissioned him to create three series of portraits—more than forty works in total. These propagandistic works immortalized the speakers of the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council of the Province of Canada, along with a collection of historical figures, such as the explorers Samuel de Champlain (c.1570–1635) and Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve (1612–1676). In 1848, Hamel painted Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), reportedly basing the composition on a work, now lost, by the Franco-Russian artist François Riss (1804–1886). Hamel’s depiction of Cartier became one of the most iconic—a status he helped solidify by printing lithographs from one of his charcoal drawings on the same subject. In the twentieth century, this image was adopted by Canada Post for various editions of stamps, cementing its place in the nation’s visual history.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements