With its four centuries of history, Quebec City invites us to look back at the ages long past that shaped it. Founded at a strategic location on the St. Lawrence River, the city imposed itself on the First Peoples who originally traded or settled there. The French conquerors developed the site into a fur trading post, then a village aiming to establish itself as a French and Catholic city, and finally, the capital of New France. The redrawing of borders by the great colonial powers brought the French Regime to an end and saw authority officially change hands with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. But Quebec City, devastated, rose from the ashes under British rule to become one of the major centres of cultural and tourist life on the American continent in the nineteenth century. After Confederation (1867), strengthened by its identity as a provincial capital, Quebec City—immortal—thrived, in part by embracing openness to others and encouraging all forms of artistic expression.

Pre-contact Indigenous Culture and the City’s Founding (1608)

Once an island emerging from the Champlain Sea, the promontory of Quebec lies where the Saint-Charles River meets the St. Lawrence, the only entryway into the North American continent from the Atlantic coast. A few kilometres southwest of the start of the St. Lawrence estuary, on the river’s northern bank, stands Quebec City. Known as Stadacona, meaning “high rock” in the Iroquoian language, the city appears as a mountain to the east, with a massif rising 105 metres high.

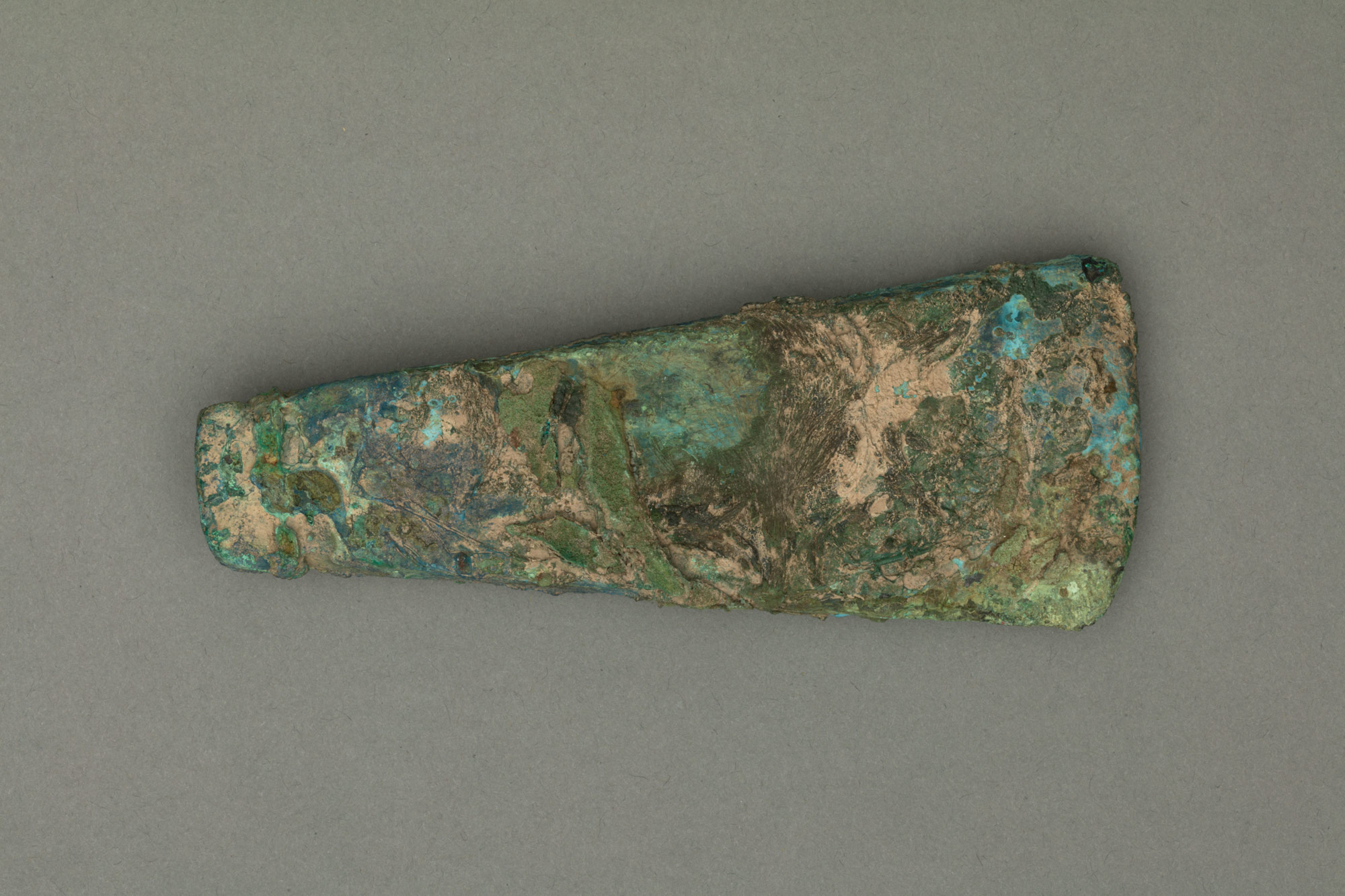

The oldest artifacts found in the area that now constitutes Quebec City were created by semi-nomadic St. Lawrence Iroquoians, who lived along the river, primarily between present-day Quebec City and Montreal, extending as far as what is now Ontario and the state of New York. “For at least two thousand years before the arrival of Europeans, the point of Quebec City was frequented by Indigenous Peoples [who] would stop there to fish for eel and to trade goods: copper, furs, foodstuffs, etc.” A cold-hammered copper axe head, dated to between 1000 and 400 BCE, reveals a design typical of the Iroquoian populations of the Centre-du-Québec region, though the copper itself comes from Lake Superior. This piece confirms the practice of “bartering raw materials” within what must have been an impressive “network of exchange and continental trade.” The Iroquoians based their way of life on hunting and agriculture, and their art on the creation of objects for everyday use as well as for ritual and sacred practices.

During the Woodland period (1000 BCE to 1500 CE), the region saw increased settlement as the St. Lawrence Iroquoians became less nomadic and developed horticulture alongside hunting, fishing, and gathering. Their ceramic art reflects these changes in lifestyle. Pottery was used to store and cook food, and its production expanded as villages became more established and techniques were refined. “Regional variations, primarily decorative, became increasingly distinctive.” For instance, the vase with ear of corn, c.1350–c.1600—discovered between 1981 and 1982 at the Masson site in the town of Deschambault (now the municipality of Deschambault-Grondines), near Quebec City—features a corn ear motif, a design that is quite rare in the region and more typical of Ontario communities. The ceramic tradition of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians would become one of the most expressive in terms of decoration.

Throughout the Quebec City region, numerous pottery artifacts provide insights into the ceramic practices of nations descended from the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, including the Wendat. “Both the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and the Huron-Wendat were village-based societies that cultivated corn, beans, and squash. Their ceramic production reflects a continuity and constant interaction with the broader Iroquoian world, where common elements, including specific ceramic traditions such as the Owasco and Pickering traditions, were shared.” Wendat women passed down the practice of ceramics from mother to daughter. The pieces they created were utilitarian, suited to their way of life, while also revealing aesthetic considerations in their form and decoration.

Numerous objects connected to the fur trade economy are among the earliest evidence of Quebec City’s material culture. The city’s foundations are rooted in the fur trade, which had been part of an extensive exchange network among Indigenous Peoples since time immemorial. Furs were traded for a variety of goods, the most prized being shell beads, or wampum. Cut, polished, and perforated, white and purple (also referred to as mauve or black) wampum cylinders were strung on cords or woven together to create ceremonial ornaments, armbands, necklaces, belts, and more. Among the Algonquian Peoples, particularly along the Atlantic coast, wampum beads served as adornments and soon became integrated into the trading economy. The Iroquoians of the interior wove the beads into necklaces, also referred to as wampums, and these took on a distinct diplomatic role. The art historian Jonathan Lainey notes that “these beaded bands of several rows of woven beads” were worn around the neck during official diplomatic meetings “with neighbouring groups, whether Indigenous or European.”

Glass beads, considered mere trinkets by Europeans, held deep symbolic meaning for Indigenous Peoples; they were sometimes strung alongside shell beads within wampums but were more commonly woven onto clothing or used to create jewellery. Long disdained in archaeological studies, glass beads “are among the most frequently found objects at archaeological sites in Quebec [and] nonetheless provide significant insights into adornment practices, trade, and interactions between Europeans and Indigenous Peoples.”

To gain access to the fur trade market, of which they had only fragmentary knowledge, European merchants relied heavily on the internal trade networks of Indigenous Peoples. The first furs from Canada—beaver, marten, otter, and lynx pelts—flooded the Parisian market starting in 1570, but it was not until Samuel de Champlain (c.1570–1635) landed in what is now known as Quebec City that the first trading post was established there. On July 3, 1608, the French explorer, draftsman, and cartographer arrived at the site that is the keystone of the valley due to its position as the terminus of oceanic communication routes.

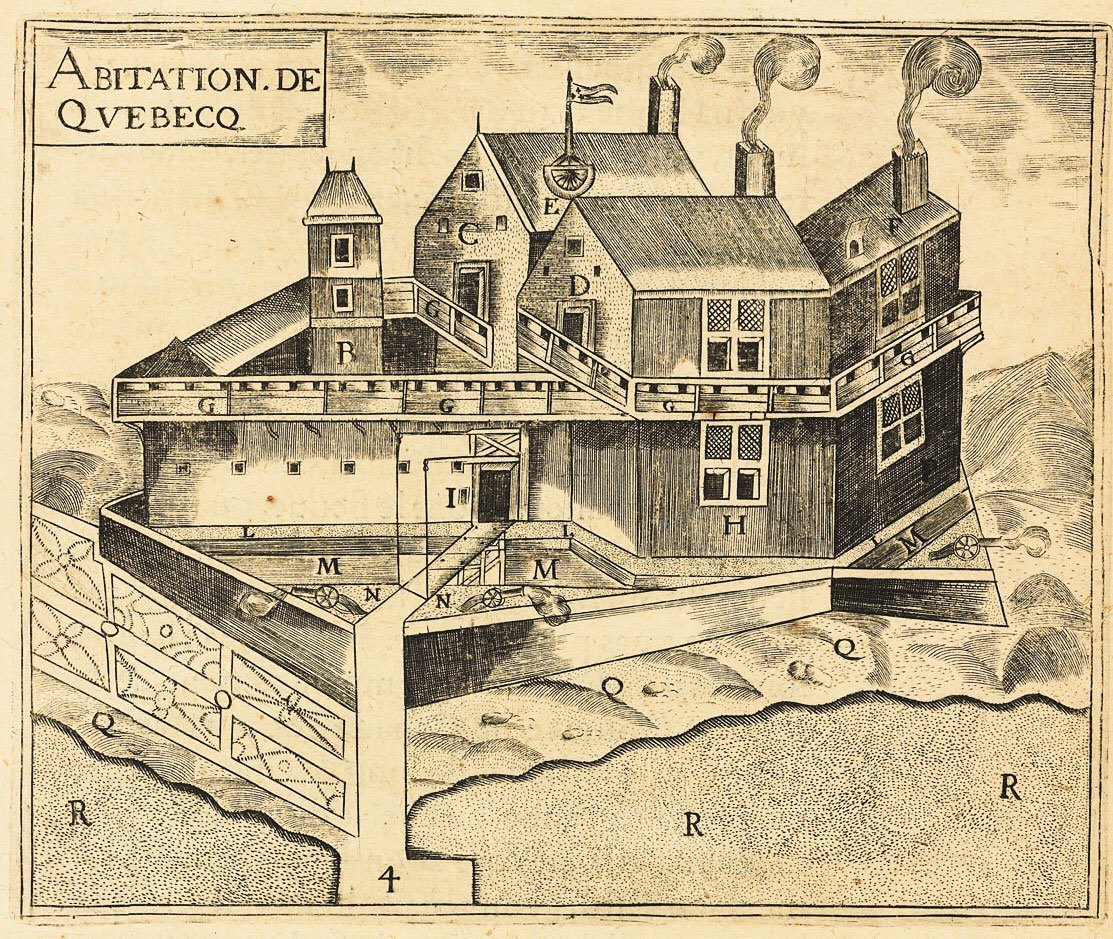

Champlain envisioned a fur trading post at the foot of Cap Diamant, where Notre-Dame-des-Victoires Church now stands in Place Royale. There, he constructed the city’s first fortified habitation (completed in 1610), consisting of several interconnected wooden buildings. His drawing of it, Abitation de Quebecq (The Habitation de Québec), 1608, reflects order and symmetry, along with a certain simplicity in the flattened depiction of space. It was later engraved and distributed in the explorer’s 1613 book Les voyages du sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine (The travels of Sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, ordinary captain for the King, in the Navy).

Champlain’s biographer states that he “left a visual portrait of the New World that alone would have sufficed to establish his fame.” But this was not the opinion of the merchants of Saint-Malo, the birthplace of the French explorer Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), who saw themselves as Cartier’s sole legitimate heirs; they regarded Champlain as an imposter and denigrated the new lieutenant’s skills by calling him a “mere painter.” But for Champlain, drawing—or what he called “portraiture”—was an important method of capturing the worlds he explored.

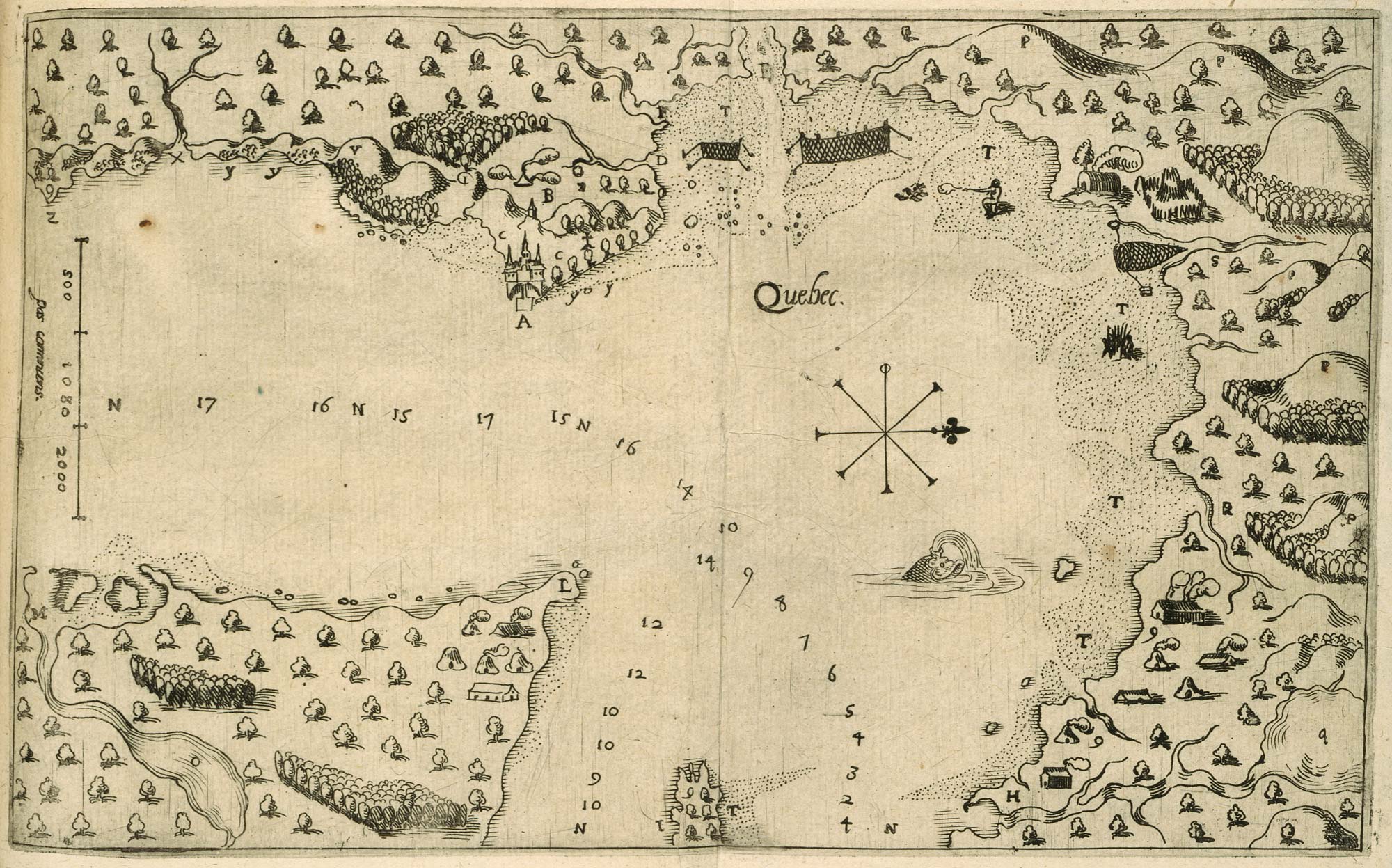

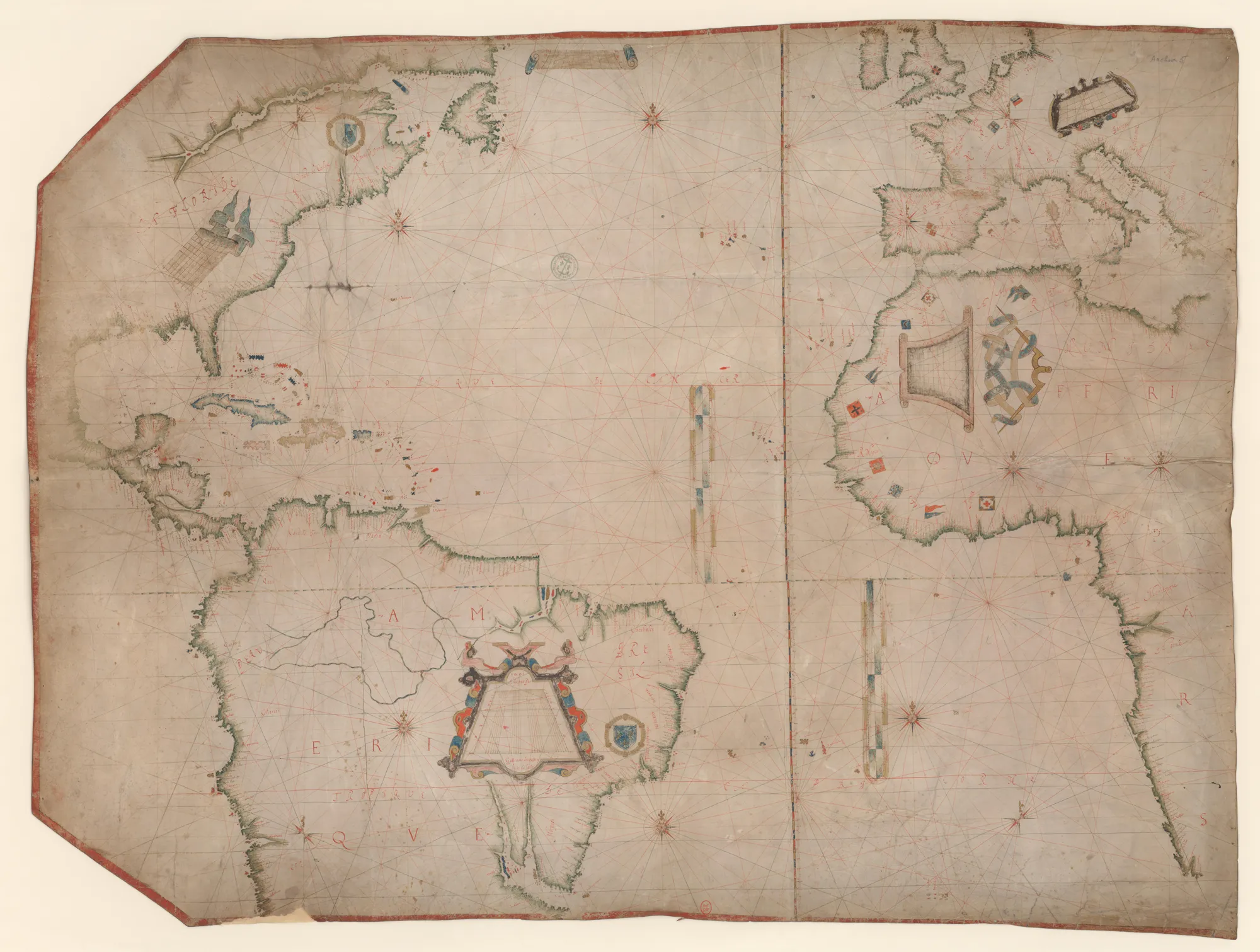

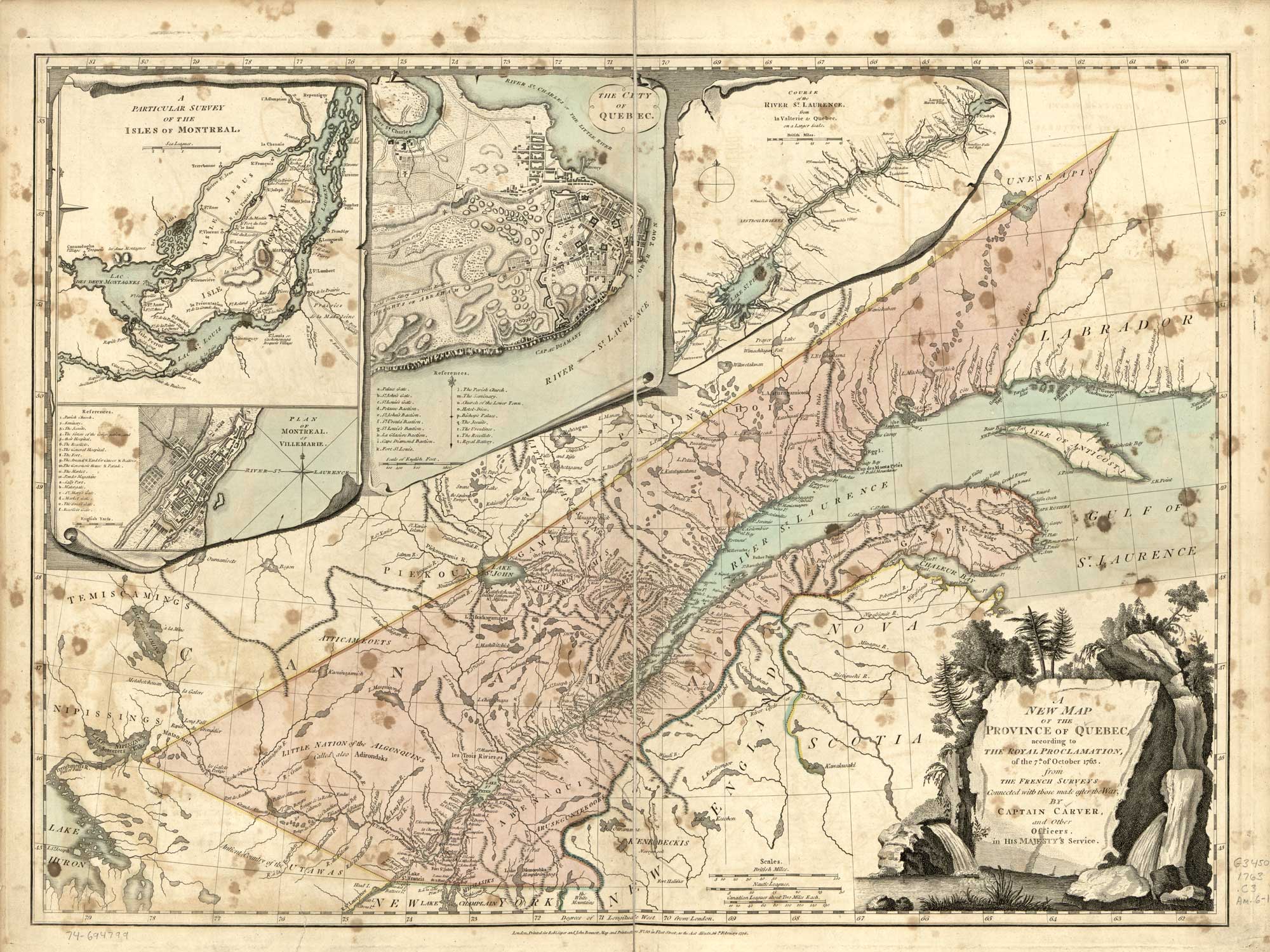

In the 1613 edition of his travel journal, Champlain published a map he is said to have drawn in 1608, showing the location of the Habitation de Québec, which is represented by a small structure crowned with three turrets. The explorer also created twenty-three maps of New France and is credited with producing the first partial depiction of Quebec City. At the time, geographic maps served as powerful symbolic markers of the territories appropriated by empires. While the name “Quebecq” was already in use on Guillaume Levasseur’s Carte de l’océan Atlantique (Map of the Atlantic Ocean) in 1601, it was Champlain’s detailed Carte géographique de la Nouvelle France (Geographical Map of New France) from 1612—his most famous drawing—that first pictured the future city.

It was not until the late seventeenth century that more detailed images of Quebec City emerged, depicting the site in all its architectural splendour, with its ornamented spires stretching skyward. In the maps of the time, Quebec City’s distinctive geography appears perfectly aligned with the social hierarchy of the French ancien régime: the feudal city, open to the river, rises from the Lower Town—a hub of commerce and trade—to the Upper Town, the seat of royal, military, and spiritual power.

Art in the Name of God and the King in New France (1608–1759)

From the seventeenth century onward, the French tradition took root in Quebec City. Samuel de Champlain provided the first images of the site at a time when French power was laying its foundations in New France. As in all North American colonies, commerce, religion, and art were closely intertwined. The French Regime (1608–1763) prospered in Quebec City through the union of throne and altar.

The Baroque tradition prevailed in the seventeenth century, in the wake of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Grand works of painting, sculpture, and silversmithing were designed to captivate, convert, and inspire the faithful through the power of art and imagery, without the need for words. It was through religious orders that the Baroque style took hold in New France—the Récollets established themselves in 1615, the Jesuits in 1625, and the Ursulines and Augustinians (Hospitallers) in 1639. Religious missions were funded by devout donors and wealthy benefactors from France, who also supported the importation of the first French artworks to Quebec City. As a result, sumptuous silversmithing pieces, reflecting the magnificence of sacred art developed in Europe, found their place in the city’s churches.

Throughout the French Regime, the Catholic Church was the primary patron of painters, sculptors, silversmiths, and architects in Quebec City. Art was highly valued in the evangelization effort, and each religious order included artists among its members. The Récollets welcomed the French painter Claude François (1614–1685), an influential figure in religious painting in New France, who was trained in the classical tradition and influenced by the theatrical effects of Baroque art. Despite his brief fifteen-month stay in Quebec City, the painter, known as Frère Luc, left a substantial body of work, including large-scale pieces intended for the city’s churches and chapels.

Frère Luc first busied himself with the reconstruction of the Récollet chapel, where he applied his skills as both an architect and a history painter. He created a large composition above the altar, Assomption de la Vierge (Assumption of the Virgin), 1671, which remains his best-known work and can still be admired today in the chapel of the Hôpital général de Québec (formerly the Récollet convent).

Frère Luc is particularly recognized for his ability to interpret religious subjects according to the context in which they were presented—in this case, in Quebec City, within the colonial reality of converting Indigenous Peoples. His painting La Sainte Famille à la Huronne (The Holy Family with a Huron Woman), c.1671, depicts Mary, Joseph, and Jesus welcoming a converted woman. In the background, the landscape evokes the cliffs of Quebec City. Within the genre of history painting, Frère Luc’s work displayed an artistry that was unprecedented. Only the painters of the nineteenth century would reach a comparable level of execution.

In New France, the Jesuits also counted artists among their members, and many worked through the first educational institution in North America, the Collège des Jésuites, founded in 1635 in Quebec City’s Upper Town to educate boys, both settler and Indigenous. Missionary painters were often only passing through, as they were called to evangelize in distant missions across a vast territory. Jean Pierron (1631–1700), a pioneer of apostolic imagery among the Mohawks in what is now New York state, was known for his paintings of hell and paradise, as documented in the writings of Marie de l’Incarnation (1599–1672). Drawings by the Jesuit missionary Claude Chauchetière (1645–1709) depict the founding and activities of the mission at Sault-Saint-Louis (now Kahnawake) in 1686. They include a rare illustration of Quebec City’s first bishop, Monsignor François de Laval (1623–1708), appointed in 1674, shown performing his episcopal duties.

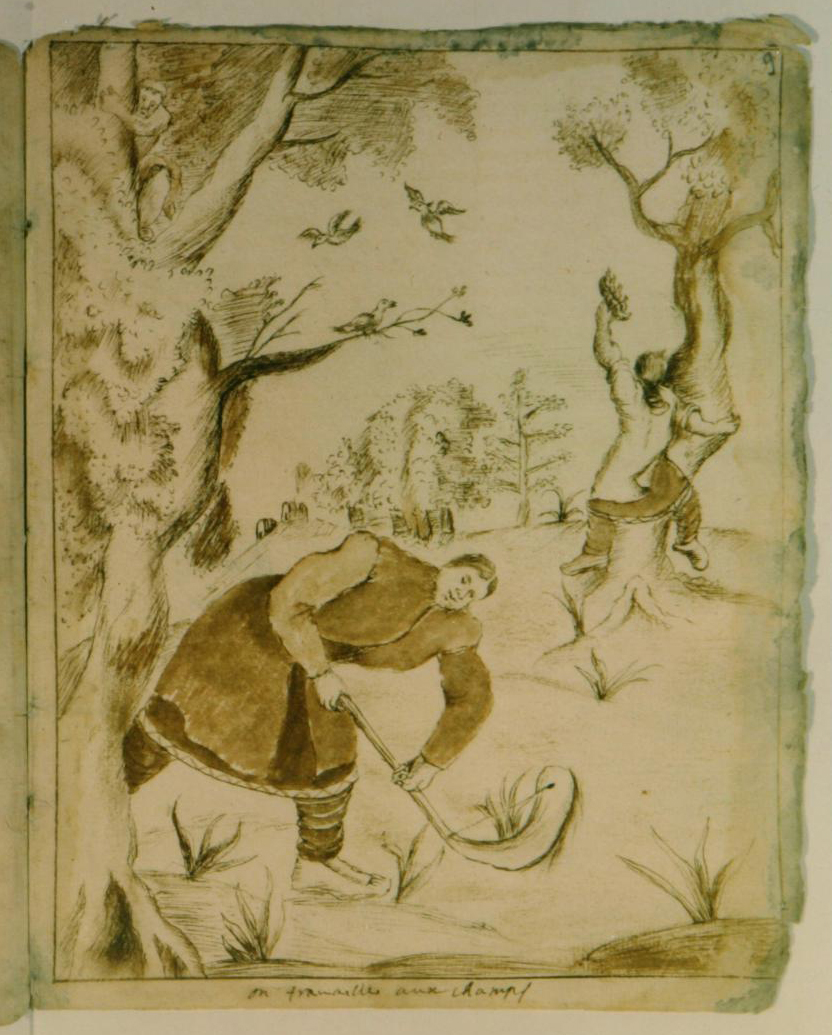

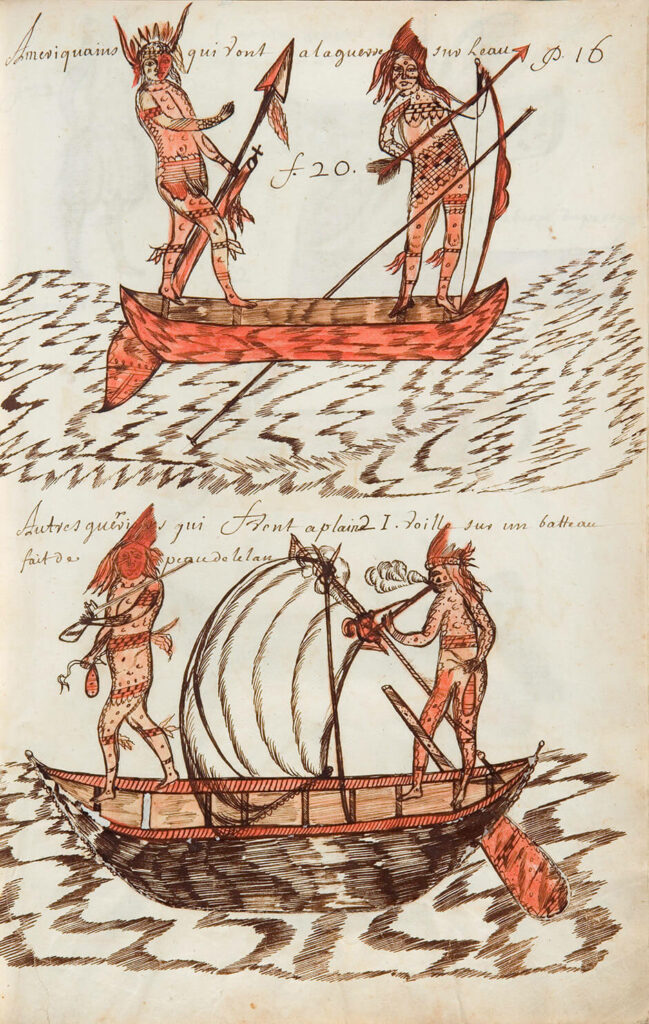

The Codex Canadensis by the missionary Louis Nicolas (1634–post-1700) stands as an exceptional record of unique, detailed drawings of the plants, animals, and Indigenous Peoples of New France, created in a period when religious subjects dominated artistic representations. “Life was harsh in the early years of this colony, and the small settler community was preoccupied with survival, trade, and business,” notes the art historian François-Marc Gagnon. “Art was a luxury, serving mainly to address the religious needs of French Catholics in New France.”

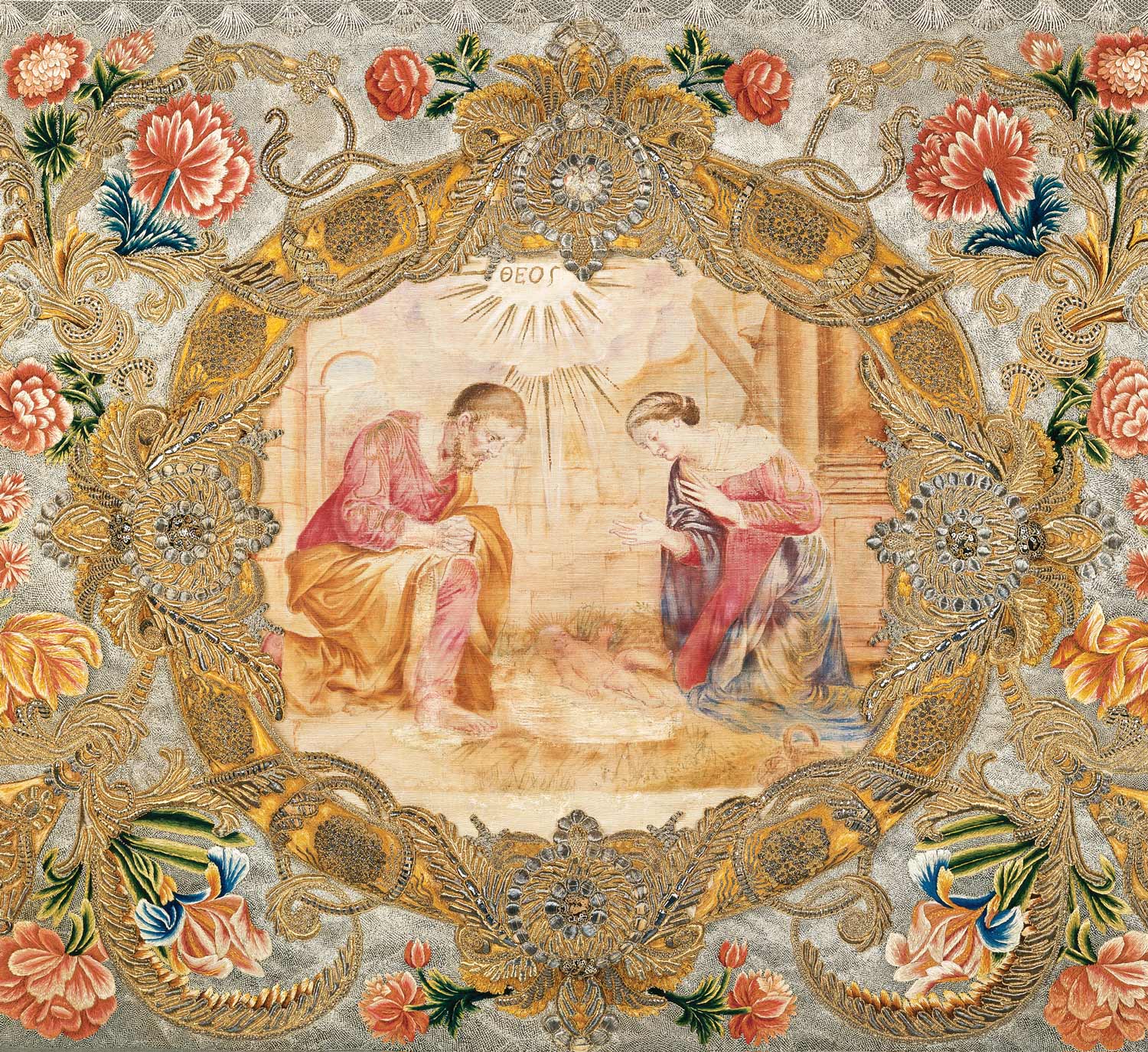

While the Jesuits primarily practised visual arts, the Ursulines excelled in embroidery, “the art of decoration par excellence,” as demonstrated by the works of Marie de l’Incarnation, founder of the congregation in Quebec City, and Marie Lemaire des Anges (1641–1717), who succeeded her in teaching needlework to the students and novices of the monastery. “Whether technical, artistic, or economic, all aspects of embroidery production practised in French convents were brought to New France in the seventeenth century by the founders of the Ursulines of Québec.” Parement d’autel dit de la Nativité (Altar Frontal Known as The Nativity), second half of the seventeenth century, exemplifies the “needle painting” practised by the nuns. In the seventeenth century, the Ursulines also developed the art of gilding, or applying a thin layer of gold leaf, which they would share with the Augustinians of the Hôpital général in the following century.

Another highlight of Quebec City’s cultural development in the seventeenth century was the founding of the Séminaire de Québec in 1663 by Monsignor Laval. It became the heart of the Catholic Church in the colony and the city’s main cultural institution until the following century. The seminary amassed a library of approximately ten thousand books spanning theology, literature, philosophy, science, and medicine.

While art flourished primarily through religious communities, royal authority also played a significant role in the cultural development of New France. King Louis XIV made Quebec City the active centre of New France when he established an absolute monarchy in 1663. The first piece of public art in Quebec City, a sculpted effigy of the young monarch—a replica of a work by the Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)—was placed in the newly created Place Royale in 1686 as a reminder of monarchical authority in the colonial capital. Royal authority was further reflected in the establishment of decision-making institutions in Quebec City—particularly the Sovereign Council, founded in 1663 to oversee political and judicial affairs. The city also developed defensive structures, including the Place d’Armes (created between 1644 and 1648), while in 1692, its fortifications were reinforced with a royal battery and ramparts featuring three guard gates encircling the Upper Town.

Art gained prominence in Quebec City with the establishment of a social elite, including the king’s representatives, who often stayed in the capital only briefly—sometimes for no more than a few months. During these visits, it was essential to display signs of authority and wealth befitting their status. From 1663 to 1759, twelve governors general and seventeen intendants succeeded one another. The ships that brought them across the ocean were loaded with luxurious personal effects and belongings, designed to reestablish, to some extent, the lifestyle they had enjoyed in France. Research has documented the splendour of the governor’s apartments in the Château Saint-Louis and the Intendant’s Palace in the early eighteenth century. The development of religious art and elite culture depended mainly on import activities.

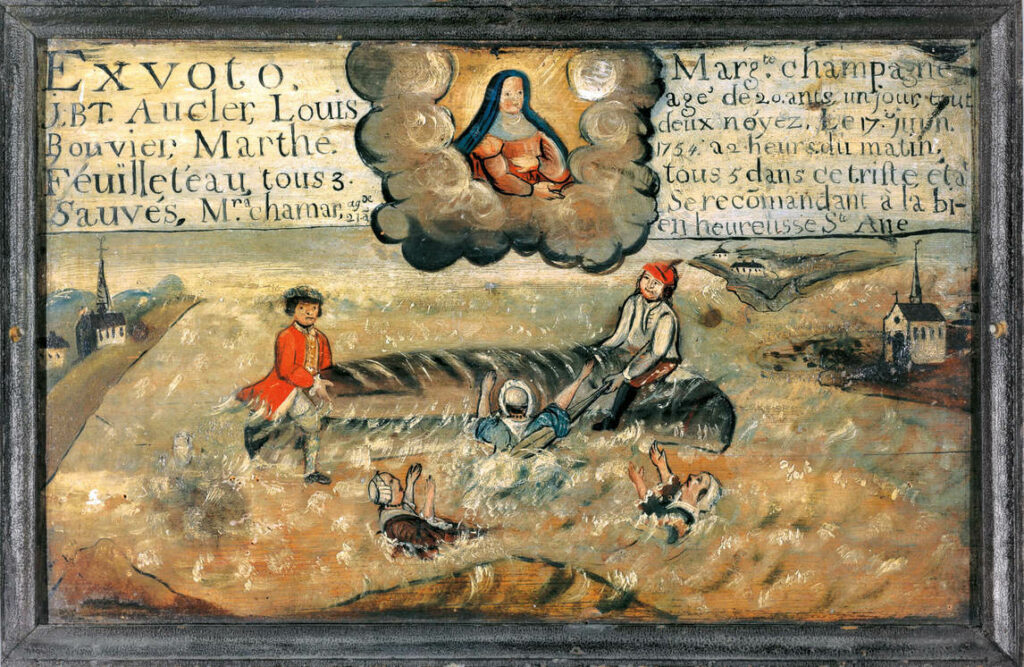

In local artistic production, there are a few examples of votive painting, introduced in the seventeenth century, depicting scenes invoking the protection of Saint Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary and patron of sailors. The Musée historique de Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré preserves valuable examples of this style of painting attributed to anonymous Canadian artists. Ex-voto de Madame Riverin (Ex-voto of Madame Riverin), 1703, for example, appeals to Saint Anne for protection during the long journey that would return the depicted mother and her children to France, while Ex-voto des trois naufragés de Lévis (Ex-voto of the Three Shipwrecked at Lévis), 1754, recounts, in a more naive style, the miraculous rescue of several passengers after the wreck of their small boat between Lévis and Quebec City.

Local production, however, was more focused on religious sculpture, gilding, and silversmithing because of the proliferation of places of worship. The ornamentation of the Ursuline Chapel (1730–1736), produced by the woodcarver Pierre-Noël Levasseur (1690–1770) and his workshop, is one of the masterpieces of this local religious production and one of the few complete sets of wood sculptures still preserved in Canada today. In the field of silversmithing, Quebec City was the primary centre of activity during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some thirty silversmiths created objects for religious and domestic use, as well as pieces intended for commercial exchanges with Indigenous Peoples.

One of the most well-known and commonly studied paintings of the seventeenth century, La France apportant la foi aux Hurons de la Nouvelle-France (France Bringing Faith to the Hurons of New France), c.1666, reflects the relationship that Quebec City religious orders, particularly the Jesuits, maintained with the Wendat, who founded the village of Jeune-Lorette (now Wendake). In the composition, the young Wendat convert is welcomed by Anne of Austria, the mother of Louis XIV, and is presenting the queen with a painting of the Holy Family. La France apportant la foi aux Hurons de la Nouvelle-France was given by the Wendat Nation to the Jesuits on the inauguration of their college’s new church in 1666. “It is known that, unlike Americans and Anglo-Canadians, the inhabitants of New France and their French-Canadian descendants maintained close and meaningful relationships with First Nations,” notes the art historian Louise Vigneault, “even when acknowledging that these relationships were driven by specific interests.” Colonizers were motivated to establish alliances with Indigenous Peoples not only to ensure their survival on barren lands, but also, and more importantly, to facilitate commerce and the fur trade.

Like the missionaries, those involved in the fur trade fostered close relationships with Indigenous communities. “Unlike the British, who preferred to wait at trading posts for furs to be delivered, the French willingly ventured deep into the territory, retrieving them on-site and thereby securing a certain degree of control over the market,” writes Vigneault. “This immersion naturally encouraged exchanges and interracial relationships.” In the years leading up to the British Conquest (1759–60), members of the Wendat Nation began marrying French Canadian women and speaking French. Driven by the fur trade and evangelization, the process of acculturation would continue well beyond the French Regime.

A Flourishing of City Views after the British Conquest (1759–60)

During the British Regime (1763–1867), the city experienced significant cultural vitality. Printing was introduced in 1764 and became the vehicle par excellence for following the progress of artists in society. Artistic production was primarily dominated by depictions of the city, which underwent extensive reconstruction after the British Conquest and continued to offer spectacular panoramas. These views attracted topographers, Romantic landscape painters, and enthusiasts of the tourism industry emerging at the end of the eighteenth century.

Under the terms of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Quebec City remained the administrative seat of the newly conquered territory, which was now named the Province of Quebec. In the Constitutional Act of 1791, the British divided the territory into Lower Canada and Upper Canada. Quebec City became home to British governors general and colonial administrators, fostering a period of cultural vibrancy during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. British influence had a decisive and positive effect on art production and the art market, and that influence extended to all fields of creativity—theatre, music, song, opera, literature, painting, and architecture—including some that had previously been prohibited by the Catholic Church under the French Regime. Quebec City developed its intelligentsia among the priests of the Séminaire de Québec and high-ranking members of the military, both francophone and anglophone. A small intellectual elite, educated and attuned to science and the arts, also emerged, encouraging the creation of literary societies. In the nineteenth century, “more than 130 such societies were founded… with nearly thirty in Québec alone.” Notably, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec was founded in 1824 at the Château Saint-Louis under the presidency of Lord Dalhousie (1770–1838), who served as governor-in-chief of British North America from 1820 to 1828.

The depiction of the city is one of the highlights of post-Conquest art in Quebec’s capital. The earliest images of this pivotal moment in history document the capture of the city by the British army, which landed at Anse au Foulon during the night of September 12–13, 1759, and unleashed thousands of projectiles, shells, incendiary bombs, and cannonballs upon the French forces. Following the attack, Hervey Smythe (1734–1811), aide-de-camp to General James Wolfe (1727–1759) and a topographical painter, returned to England with several sketches, including the popular scene of the city’s capture, entitled A View of the Taking of Quebec, September 13, 1759, which was engraved and widely published beginning in 1760. Smythe focuses on the troops ascending to the Plains of Abraham by scaling the cliffs bordering the river. Richard Short, a naval officer aboard the HMS Prince of Orange and also a topographical painter (active from 1748 to 1777), created twelve views of Quebec City in 1759, which he published in London in 1761. These works document the extensive destruction of the most symbolic sites of power—churches, convents, palaces, and castles—in the defeated capital.

Beyond the devastation, these images of the city reveal its magnificence. Quebec City is a place cherished by artists and portrayed in drawings, engravings, oil paintings, and watercolours. Surrounded by ramparts, the Upper Town reflects the city’s defensive character and has a distinctive aura. In 1843, the English author Charles Dickens wrote of Quebec City’s landscape: “The impression made upon the visitor by this Gibraltar of America: its giddy heights; its citadel suspended, as it were, in the air; its picturesque steep streets and frowning gateways; and the splendid views which burst upon the eye at every turn: is at once unique and lasting.” The fortress envisioned since the early days of the French colony was finally erected atop Cap Diamant between 1820 and 1850. Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry (1682–1756) had pictured the Citadel as part of the fortification project he designed and supervised in the previous century. In the twenty-first century, the famous fortifications still encircle the historic district of Old Quebec, making the capital “the only fortified city in North America north of Mexico.”

Perched atop Cap Diamant, motionless and powerful against the winds whipping the Union Jack, the Citadel became the quintessential image for Romantic painters and writers in the nineteenth century. Just a few years before Dickens offered his famous description, John Richard Coke Smyth (1808–1882) painted Vue de Québec (View of Quebec City), 1838–39, a vivid example of this trend toward Romantic landscapes in the depiction of the city. His piece shows the rugged coastline of the cliff, atop which the Citadel stands triumphant, unshaken by the turbulent sea and the vast, cloud-filled sky.

English topographical painters and amateur artists offered picturesque, sometimes Romantic, but also realistic views of Quebec City. The practice of watercolour painting was introduced by officers of the British garrison trained at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, near London, including the military topographer James Pattison Cockburn (1779–1847). Cockburn produced so many works depicting Quebec City that his collection functions as a visual and tourist guide, inviting exploration of the city’s charming character from various angles, shaped by the distinct areas of the Lower Town and the Upper Town.

The English amateur painter Millicent Mary Chaplin (1790–1858) created about one hundred watercolours and drawings during her four-year stay in Quebec City. She depicted numerous urban scenes, including panoramic landscapes such as View from Mrs. Chaplin’s Dressingroom Window, Quebec, 1839, as well as more intimate views of her own surroundings. Her attention inevitably turned to winter, and she recorded the aftermath of a memorable February 1842 storm, with massive snowdrifts filling her courtyard and nearly reaching the roof of her stable. A few months later, Chaplin added a summer version of the view from her garden—a counterpart that illustrates the artist’s appreciation for the stark contrasts of Quebec City’s climate.

The Scottish engraver James Smillie Jr. (1807–1885), who had immigrated to Quebec City with his family as a young teenager, trained in London with the support of Lord Dalhousie, a patron who took many artists under his wing. Upon his return to the colony, Smillie contributed to the 1829 book Picture of Quebec, the first illustrated guide to the city, featuring seventeen plates of panoramic views and scenes of urban life. Among them is the lively Quebec Driving Club meeting at Place d’Armes, c.1826, which depicts a sled race held in the Place d’Armes, bordered by the courthouse on the left and the Anglican Cathedral of the Holy Trinity on the right. A few years later, in 1834, the wine merchant, author, and publisher Alfred Hawkins (1792–1854) also contributed to the portrayal of the city with the publication of his book Hawkins’s Picture of Quebec, with Historical Recollections. His passionate literary descriptions—including his praise of the Citadel as a “chef d’oeuvre of nature and of art”—are accompanied by several views of the city.

-

Cornelius Krieghoff, The Royal Mail Crossing the St. Lawrence, 1860

Oil on canvas, 43.2 x 61 cm

Private collection

-

Cornelius Krieghoff, The Steamship Quebec, 1853

Oil on canvas, 68 x 93.5 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The imagery of Quebec City also proliferated in oil painting during the nineteenth century, thanks to artists not only from the United States and Great Britain but also from various European countries. Often just passing through, these artists travelled from town to town according to market demands. Louis-Hubert Triaud (1790–1836), James Bowman (1793–1842), Henry Daniel Thielcke (1788–1874), Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), Robert Clow Todd (c.1809–1866), and Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872) all offered sensitive depictions of bourgeois, rural, and Indigenous life in Quebec City. For example, Krieghoff, renowned as an exceptional visual storyteller, captured the royal postal service during the summer season with The Steamship Quebec, 1853, and a few years later, he produced an epic rendering of the same service in a winter setting, The Royal Mail Crossing the St. Lawrence, 1860.

These artists created scenes that highlighted the city, its surrounding sites, and its seasonal pleasures, and they gained recognition through local newspapers. Upon his arrival in the region, the Englishman Robert Clow Todd was announced in La Gazette de Québec on January 27, 1834, as a painter of houses, signs, carriages, and ornaments. He eventually settled in Toronto, but he spent nearly twenty years in Quebec City, where he ran a studio, taught painting, and produced numerous landscapes and genre scenes portraying the pleasures and pastimes of the urban bourgeoisie. His favourite subject was the “sugar loaf” at the foot of Montmorency Falls, one of Quebec City’s most famous natural wonders. Todd was also entrusted with prestigious commissions, including The Allan Gilmour and Company Shipyard at Anse au Foulon, Quebec City, Seen from the West, 1840, one of two splendid renderings of the shipyard. This work highlights the importance of the timber trade, which had replaced fur as the foundation of Quebec City’s economy.

The Rise of Local Creation, from Painting to Craftsmanship, in the Nineteenth Century

Local painting, produced by artists native to Quebec City, also flourished during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as did Wendat artistic creation. This period was marked by the emergence of the first generation of painters originating from the capital and its surrounding region. Many of these artists—including Joseph Légaré (1795–1855), Jean-Baptiste Roy-Audy (1778–c.1846), Antoine Plamondon (1804–1895), and Théophile Hamel (1817–1870)—came to be seen as the pioneers of Quebec City painting. They learned their craft by restoring religious paintings from the Desjardins Collection—180 works sent from Paris to Quebec City by two Catholic priests, the Abbés Desjardins, in 1817 and 1820. This collection became an inexhaustible source of European models for practice and copying. In the absence of a formal art school in the capital, it served as a vital reference.

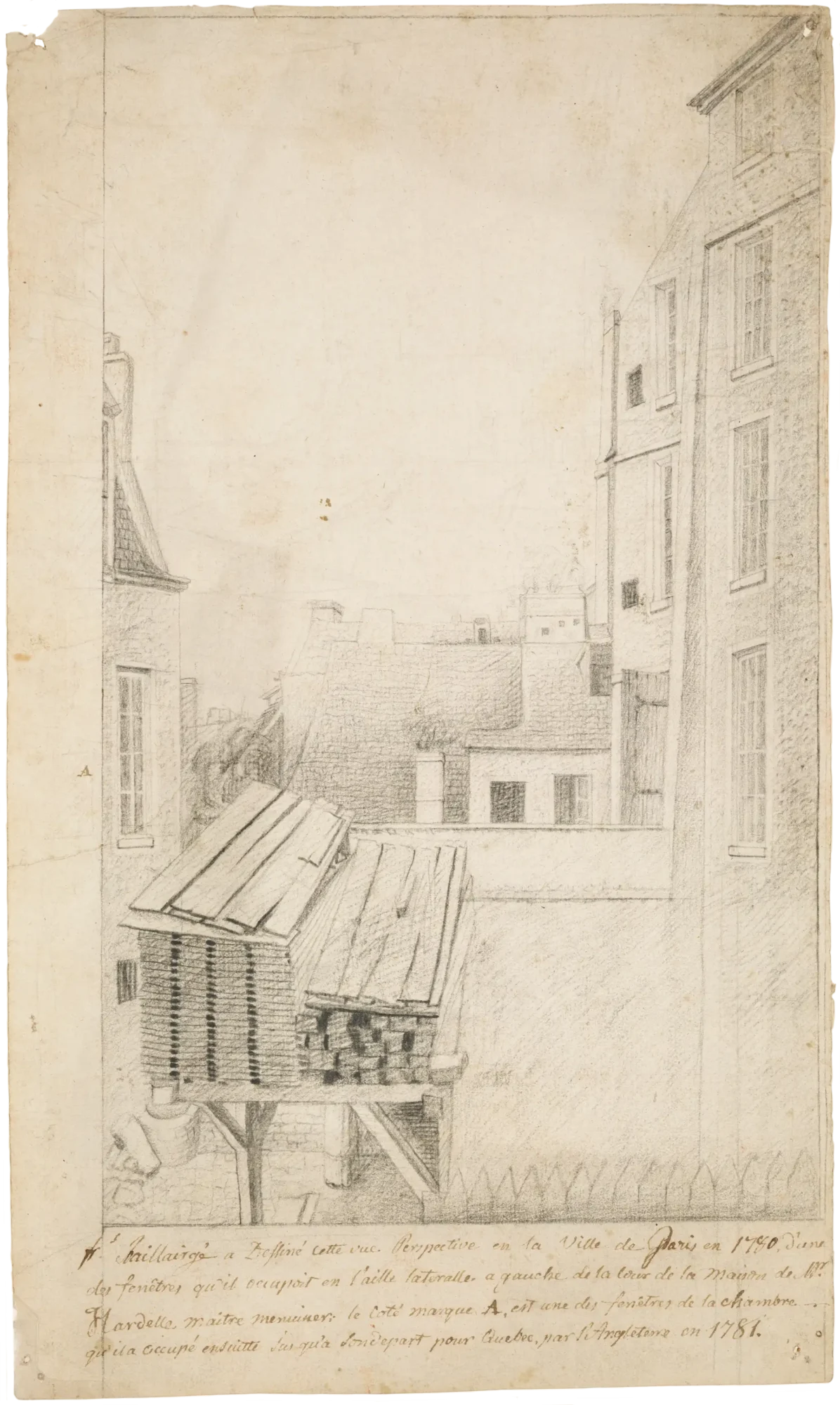

Until the eighteenth century, art was taught in Quebec City through a master–apprentice relationship. During the nineteenth century, artists began offering private drawing lessons, advertised in newspapers. François Baillairgé (1759–1830) exemplified this approach and became a drawing master, notably teaching Légaré. Soon, colleges began offering lessons; the Séminaire de Québec introduced drawing courses in 1833, with Plamondon as its first instructor. The talented and versatile Italian miniaturist Gerome Fassio (1789–1851), who spent about twenty years in Quebec City, was a sought-after private painting and drawing instructor, and he also taught drawing at the Séminaire from 1839 to 1840.

Some artists native to Quebec City had the opportunity to refine their training in Europe. Baillairgé was the first in a long line of local painters to be sent to France for formal studies, supported by patrons connected to the Church or the government. With the help of the Séminaire de Québec, Baillairgé studied for two years at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, where his training focused on drawing. The silversmith Laurent Amiot (1764–1839) also honed his craft in Paris during the 1780s. The French model remained an attractive standard for Quebec City artists well into the twentieth century.

The art market in Quebec City was energized by the new generation of painters, who embraced various pictorial genres. Religious history remained formative, and the Church continued to be one of the city’s main patrons, but genre painting, landscape, and especially portraiture held great appeal for the bourgeois clientele of the nineteenth century. Because of the rise of the bourgeoisie and its desire for recognition, portraiture attracted almost all painters of the time—particularly Roy-Audy, Plamondon, and Hamel, who practised it with great virtuosity for a broad range of clients.

Légaré was not only a painter but also a passionate collector with an entrepreneurial spirit, and he built a personal collection that at the time of his death in 1855 had more than a thousand pieces, including 162 works of Canadian and European art. Légaré purchased about thirty paintings from the Desjardins Collection, making copies that he successfully sold to religious parishes, which sometimes paid him with paintings. He also acquired many prints from the auctioneers John Christopher Reiffenstein and Giovanni Domenico Balzaretti.

To showcase his collection, Légaré exhibited it to the public in 1829 in the space of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, on the first floor of the Hôtel Union. This was the first of many free exhibitions of his collection, which grew year by year to include paintings of all kinds: religious and genre scenes, landscapes, portraits, and still lifes. Between 1833 and 1872, Légaré also established three painting galleries in the Upper Town. Two were housed in his family residences on rue Sainte-Angèle (the first active between 1833 and 1835, and the second between 1852 and 1872), while another operated for two years in the home of Légaré’s business associate on côte de la Fabrique. This third gallery was described at its opening in 1838 as a “temple of the fine arts in the city of Québec” for the vibrant activities it hosted, including concerts, painting classes, and exhibitions of contemporary artists.

These galleries proved to be more educational than profitable, bringing together the city’s francophone intellectual elite and members of anglophone society, and primarily offering professional and amateur artists access to diverse and high-quality artistic models. During his lifetime, Légaré did not establish a museum in the strict sense, although he became involved in discussions to create a permanent art repository as early as 1845. Thirty years later, in 1875, the Pinacothèque at l’Université Laval—the first permanent art museum in the city and even the first art museum in Canada—was established thanks to the Séminaire de Québec’s acquisition of Légaré’s collection. Université Laval, the first French-language university in North America, founded in Quebec City in 1852, was thus enriched with an art museum.

The artistic production of the First Nations also flourished in Quebec City during the nineteenth century. The Wendat Nation, for example, developed a local craft tradition rooted in its ancestral heritage. At the time, not many Indigenous people had been introduced to art forms like painting. But Zacharie Vincent Telari-o-lin (1815–1886), from the community of Jeune-Lorette (now Wendake), was an exception.

In addition to his roles as a community leader, father, hunting and fishing guide, and snowshoe maker, Vincent began painting seriously around the 1850s, producing genre scenes, landscapes, and portraits while exploring a variety of techniques, including oil painting, pencil drawing, charcoal, ink, and watercolour. He expressed himself in a naive style, often employing multiple perspectives, as seen in Les chutes de Lorette (Lorette Falls), c.1860, a work that appealed to Quebec City’s bourgeois and military classes, as well as to the many tourists visiting Jeune-Lorette. But it was through self-portraits that he distinguished himself and asserted his status as a painter, a craft he is believed to have learned through contact with Quebec City artists such as Antoine Plamondon, who portrayed him in their works.

In 1840, Vincent was featured in a group portrait painted by Henry Daniel Thielcke and commissioned by the new honorary chief of Jeune-Lorette, Robert Symes, a lawyer and justice of the peace in Quebec City. At the centre of the composition sits Symes, surrounded by other chiefs and members of the Wendat community, as he takes part in a ceremony that reportedly drew some two hundred visitors from the city. On the left side of the painting, the young Vincent can be seen wearing a ceremonial silver headdress of his own making. Passed from father to son within a chieftainship, a headdress was typically crafted from materials such as moose hair, porcupine quills, leather, and feathers, but some featured pewter rings made by French silversmiths and used as trade currency. This commemorative portrait is a valuable record of colonial interracial cultural exchange, expressed through the attire of these chiefs: military frock coats adorned with bracelets and armbands, top hats as symbols of authority, silver medals, and arrow sashes. Its popularity led to the printing of lithographic reproductions—in both black and white and colour—starting in 1842.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the traditional crafts of the Wendat community—canoe building, snowshoe making, embroidery work, basketry, and more—continued to thrive. These handcrafted products were highly sought in Quebec City’s artisan market and were sold in a few shops in the city. In 1837, William S. Henderson settled there and opened a hat shop on rue De Buade, near the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Québec and the famous côte de la Fabrique, one of the oldest streets in the city. (John Hamilton Simons would open a haberdashery there in 1840.) Henderson’s business prospered partly through collaboration with the Wendat, who supplied him with furs and handcrafted items to sell, and would later become Holt Renfrew, a luxury department store that still operates in several Canadian cities.

The creativity of Wendat craftswomen is showcased in a variety of pieces, such as woven baskets or striking works like a hand fan from around 1860, “an object both refined and exotic” that features ostrich feathers and porcupine quills and catered to the tastes of the bourgeoisie of the time. The ceremonial skirt and redingote dress, c.1875, is a remarkable example of moose-hair embroidery, an important tradition in the Wendat culture. The harvested moose hair is washed and dyed, then embroidered onto garments, such as the impressive redingote, or pieces of bark or leather.

Architecture and the Identity Movement after Confederation (1867–1900)

In the mid-nineteenth century, modernization began transforming Quebec City. Around 1860, the once-thriving port gave way to the first mechanical industries centred in the Saint-Roch district, including shoe manufacturing, tanning, garment production, and furniture making. Technological innovations and industrialization impacted artisanal and artistic activities. Painting and engraving, for example, faced competition from new technologies: photography became established in Quebec City when the Livernois family firm opened its first studio in 1854. Within this prominent dynasty of photographers, Jules-Ernest Livernois (1851–1933) emerged as one of Canada’s pioneers, alongside Montrealers William Notman (1826–1891) and Alexander Henderson (1831–1913). Livernois’s work was distinguished by its abundance, diversity, and aesthetic quality, making him the dominant photographer in the city in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

This period of urban progress in Quebec City reached its peak with the arrival of the railway (1879) and electricity (1883), followed by the development of the streetcar (1887) and the construction of the Québec Bridge (1917) and the Price Building (1929), the city’s first skyscraper. The capital of the province of Quebec within the new Dominion of Canada, as established by the British North America Act in 1867, was buzzing with activity: industry was transforming the city and the arts, while extensive urban planning projects were underway.

Five years after Confederation, in 1872, the new governor general of Canada, Lord Dufferin (1826–1902), established an official residence at the Citadel, where he stayed regularly. A cultured aristocratic diplomat with a passion for Romanticism, Lord Dufferin sought to highlight the city’s medieval heritage to create a thriving tourist destination during a period marked by the democratization of travel. In the second half of the nineteenth century, European and North American elites and bourgeoisie travelled extensively, including to Quebec City, with its historic architectural heritage and its distinctive geography. Against this backdrop, the authorities launched major urban development projects.

Neo-Palladianism, which flourished in England from 1720 to 1770, spread to Lower Canada in the nineteenth century and influenced new architectural constructions. Buildings in Quebec City became increasingly imposing, with stone facades and porticos with pediments and colonnades inspired by the palaces of the Italian Renaissance. Embracing Victorian architecture’s penchant for borrowing from historical styles, the architect Eugène-Étienne Taché (1836–1912) blended distinctive characteristics of French medieval and Renaissance fortresses to create the Château style. He trained under Charles Baillairgé (1826–1906), whom Lord Dufferin had commissioned to extend the magnificent terrace along the river (inaugurated in 1879 and later named in his honour).

Taché also designed Quebec City’s armoury in the Château style, using massive stone and a flamboyant fifteenth-century decorative scheme that included false arrow-slit windows, turrets with conical roofs, and a central portal. Ten years later, the New York architect Bruce Price (1845–1903) applied the Château style to the Château Frontenac hotel, abandoning “the classical symmetry of these models in favor of the picturesque eclecticism popular in the late 19th century.” The Château style unfolds in its multicoloured surfaces, its steeply sloped roofs, its towers and turrets, and the asymmetrical profile of its five wings and central tower. Built in 1892–93 on Cap Diamant, on the site of Champlain’s first fort and the former Château Saint-Louis (destroyed by fire in 1834), the Château Frontenac perpetuates the romantic image of the city. The fortress-like château atop the cliff reinforces the perception of Quebec City as a French medieval town. A powerful symbol of Quebec tourism, “the most photographed hotel in the world” underwent several expansions between 1908 and 1993. Its iconic tower was erected in 1924.

Taché’s contributions extend beyond establishing the Château style in Quebec City: he is also credited with fostering a public art trend deeply rooted in a strong nationalist sentiment. Since Confederation, the French Canadian people—referred to as Québécois starting in the 1960s—had expressed their identity through commemorative art placed in the city’s squares, parks, and gardens. Magnificent and imposing monuments were erected in memory of the events and people who shaped the province’s history.

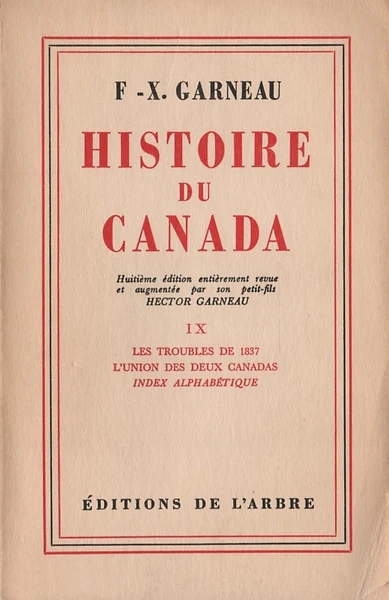

This identity-building movement is rooted in the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837–38, in which the government of Louis-Joseph Papineau (1786–1871) took up arms against British colonial authorities. Although the rebellion was unsuccessful, it gave rise to a nationalist awakening among Quebec City’s intellectual elite. Between 1845 and 1852, the historian François-Xavier Garneau, a member of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, published his Histoire du Canada. This influential work served as a subtle rebuttal to degrading statements in the Durham Report (1839), which had advocated for the assimilation of French Canadians and stigmatized them as a people “with no literature and no history.” This context resulted in the emergence of a distinctly French Canadian sensibility, one that permeated all creative fields in the twentieth century.

A francophile and ardent nationalist, Taché designed the city’s Parliament Building (built 1877–86). It is to Taché that the province owes its motto, Je me souviens, which he inscribed on the building’s facade. The facade is also richly adorned with a vast array of statues depicting key figures in the history of Quebec City and Canada: individuals from First Nations, founders, explorers, soldiers, missionaries, politicians, and influential public administrators. This pantheon was created by the leading artists in bronze statuary and heraldic sculpture—most notably Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917), Alfred Laliberté (1877–1953), Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Côté (1869–1937), and Sylvia Daoust (1902–2004)—as part of this ambitious commemorative project, which continues to grow with the addition of new sculptures to this day.

From Paris, where he honed his bronze sculpting skills, Hébert secured the prestigious commission for several full-length sculptures for the Parliament Building, including those of Major-General James Wolfe and the Marquis de Montcalm, as well as Halte dans la forêt (A Halt in the Forest), 1889, a piece placed facing the main entrance. Presented at the 1889 Paris Exposition, this work earned Hébert a bronze medal—a groundbreaking achievement for a Canadian artist. Like Pêcheur à la nigogue (Fisherman at the Nigogue), which was installed on the facade in 1891 and depicts an Indigenous figure spearing a fish, Halte dans la forêt portrays traditional Abenaki hunting practices. These pieces reflect Hébert’s French academic training, which was deeply influenced by classical statuary and encouraged the idealization of his subjects. They also aligned with the identity-building movement of the time, and served as a celebration of the First Nations in Quebec.

Twentieth-Century Regionalist Painting and Institutionalization (1900–60)

At the turn of the twentieth century, painters in and around Quebec City were deeply concerned with preserving national memory, giving rise to a powerful regionalist art movement. Their works depict the trades, legends, and landscapes of French Canada, which industrialization threatened to erase. Against the backdrop of the appropriation of vast western Canadian territories to make way for the railroad, this regionalist trend reflected a nostalgic quest for the country’s origins in the St. Lawrence Valley. The early decades of the century were also marked by the institutionalization of art in Quebec’s capital.

In search of traces of tradition and national history, painters from Montreal and Toronto—including William Brymner (1855–1925), Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), Edmund Morris (1871–1913), and William Cruikshank (1848–1922)—headed east. These artists were anglophones, for the most part, and financially independent or making a living through their art. Together they formed the bande de Beaupré, a group that for about a decade (1895–1905) would gather to paint in the village of Beaupré, roughly forty kilometres from Quebec City. Renowned for its basilica, which draws Catholic pilgrims from across North America, Beaupré faces Île d’Orléans, home to Horatio Walker (1858–1938), an artist who worked in the tradition of the Barbizon school and French realism.

Like other members of the bande de Beaupré, Walker depicted villages, farms, and peasants at work, immortalizing scenes of rural life on canvas or in quick sketches. Labour aux premières lueurs du jour (Ploughing—The First Gleam), 1900, and La traite du matin (The Morning Milking), 1910, are typical compositions that elevate their subjects, portraying them in expansive settings that convey a sense of dignity. Landscape painting was also a favoured genre for Cullen, Morrice, and Morris, who, captivated by Quebec City and its surroundings, depicted various summer and winter scenes that rank among the finest examples of Canadian Impressionism. In The Ferry, Quebec, 1907, Morrice uses simplified shapes and a muted colour palette to compose the river and landscape. The 1907 painting retains the directness and liveliness of the quick sketch Morrice had created a decade earlier, On the Ferry Boat from Lévis, Quebec, c.1897.

This regionalist movement also found expression within the Société des artistes de Québec, the first organization in the capital explicitly dedicated to the visual arts. Founded in 1910 and incorporated in 1915, the society had a mandate to foster an appreciation for fine arts by organizing exhibitions, meetings, and lectures. It held its first exhibition in 1916, and three years later, it merged with the Société des arts, sciences et lettres de Québec, which published Le Terroir, a monthly journal aptly titled to reflect the concerns of the time.

Painters native to the city joined the ranks of the society, including Charles Huot (1855–1930), Eugène Hamel (1845–1932), Henry Ivan Neilson (1865–1931), and Edmond LeMoine (1877–1922). Inspired by themes of the terroir, which means “soil,” these painters and illustrators produced landscapes and rural scenes of Quebec City and its surroundings, as well as interiors of homes, bringing quintessentially Québécois characters to life. Huot captured these regionalist themes in paintings such as Québec vu du bassin Louise (Quebec from Bassin Louise), 1902, and Le père Godbout (Father Godbout), c.1897. His piece L’atelier du peintre (The Painter’s Studio), 1909, shows Huot’s workspace and his main plaster models, with a student busy in the background.

The regionalist trend developed alongside the emergence and consolidation of the institutional arts scene in the capital. In the 1920s, at the urging of Provincial Secretary Louis-Athanase David (1882–1953), the Liberal government enacted several laws that laid the foundation for Quebec City’s cultural policy. David’s initiatives led to the establishment of a scholarship program for advanced studies abroad in 1920 and, in 1922, the founding of the École des beaux-arts de Québec (ÉBAQ), the first public institution of its kind in Canada (and the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, inaugurated in 1923). His Provincial Museums Act of 1922 led to the creation of the Musée de la province de Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). The museum opened in 1933 on the Plains of Abraham, with Gérard Morisset (1898–1970) as its first curator. From 1937 to 1969, Morisset, a key figure in the development of art history in Quebec, worked on an extensive inventory of the province’s artworks. In many respects, this ambitious project aligned with the goals of the regionalist movement in painting, which sought to preserve cultural memory. Driven by a strong sense of heritage, Morisset aimed to document, and thus preserve, all artworks, whether major or minor, produced across the province.

The establishment of the ÉBAQ in 1922 fostered the growth of the local artistic community. Students could be trained in painting, sculpture, architecture, engraving, or decorative arts, following the model of the École des beaux-arts in Paris, where the academic tradition continued to set the standard for artistic instruction. Until 1970, the school operated within the city’s francophone intellectual hub and alongside other cultural institutions, such as the music conservatory (1944) and the theatre conservatory (1958), performance venues, fashion stores like John Darlington, Holt Renfrew, and Simons, and art galleries, including one of the city’s oldest, Galerie Zanettin (1885). From 1924 to 1929, the school’s first director, Jean Bailleul (1876–1949), a Belgian sculptor and graduate of the École des beaux-arts in Paris, worked to revive traditional French art in the province. Resistant to the avant-garde movements of the School of Paris—represented by figures like Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Marc Chagall (1887–1985)—Bailleul surrounded himself with French colleagues who formed the school’s first teaching cohort, laying the foundation for French-style academic training in Quebec City.

Over the years, the ÉBAQ welcomed several Québécois students who would go on to achieve great renown. Among them was the young Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), who studied at the school from 1922 to 1926 before pursuing a career primarily in Paris and Montreal. Pellan was one of the first recipients of the provincial scholarship for advanced studies abroad, which allowed him to study in France until 1939. With the outbreak of the Second World War (1939–45), he returned to Canada and, in June 1940, held a retrospective exhibition of his Parisian modernist works in his hometown, sparking a small revolution in the art scenes of both Quebec City and Montreal.

Soon, the ÉBAQ’s teaching staff was enriched by local professors, including Henry Ivan Neilson, who succeeded Bailleul as director in 1929 and introduced printmaking instruction—a first for a Canadian public school. A master printmaker fond of etching and drypoint techniques, Neilson enjoyed experimenting to capture the atmosphere of his subjects. Navire de transport du bois, Québec (Timber Ship, Quebec), 1915, for example, vividly depicts the industrialization of the port with bold, dynamic lines. Neilson would go on to teach Simone Hudon (1905–1984), who became part of the next generation of the school’s educators during the 1930s and beyond. Teaching positions at that time were increasingly filled by graduates of the Quebec City and Montreal art schools, such as Omer Parent (1907–2000), Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–1990), Raoul Hunter (1926–2018), and Marius Plamondon (1914–1976). These artists brought a wave of modernity to the teaching of painting, which remained predominantly figurative in Quebec City.

While serving as a professor at the ÉBAQ from 1946 to 1952, the painter Jean-Philippe Dallaire (1916–1965) created three large allegorical pieces representing the core subjects of the school’s curriculum. To produce these works, Dallaire drew inspiration from the decorative style of Jean Lurçat (1892–1966), a leader in the revival of tapestry art in twentieth-century France, with whom he interned in 1949. The expansive 1947 compositions, depicting the plastic arts, advertising and decoration, ceramics, and tapestry (a discipline desired but absent from the school’s program), reveal similarities with the renewed figurative language of Picasso. They showcase Dallaire’s openness to Surrealism and his use of unabashedly unconventional motifs. At this same time, the authority of the traditional academic model, championed by Quebec City’s political and religious leaders, was beginning to erode.

On May 9, 1945, the day after VE Day, a group of students and professors turned up at the Gare du Palais to warmly welcome the French avant-garde painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955), who had been expatriated to the United States at the start of the war. Léger gave a lecture at Université Laval titled “La libération de la couleur,” and that was followed by the first screening of the film Léger en Amérique (1945) and the launch of the book Fernand Léger: La forme humaine dans l’espace (1945). Léger’s visit to the capital, and to Montreal the following day, marked a pivotal moment in the history of Québécois art.

This event was one of the catalysts for reforms that would modernize art education in the two fine arts schools of the province. “From that moment, in Québec as in Montréal, Omer Parent and his close friend Alfred Pellan began advocating for reforms and new approaches… inspired by the ‘Bauhaus’ (Dessau, Germany) and László Moholy-Nagy’s experiments at the ‘School of the Art Institute’ (Chicago, United States). They sought to ‘tear down academicism.’”

A Multiplicity of Spaces and Modes of Expression in Contemporary Art (1960–2025)

In the 1960s, the Quiet Revolution dealt a final blow to the grip of tradition and the Church on Quebec society. The effects of this were reflected in the emergence of a universal, free, and engaged artistic expression that left its mark on the capital. Art broke away from traditional exhibition spaces and liberated itself beyond their walls.

The early signs of this expansion emerged some twenty years before the Quiet Revolution, in 1938, when the professor, painter, and critic Jean Paul Lemieux bemoaned the state of art in the province. He called for Quebec to follow the example of the American Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project, which provided jobs for artists during the Great Depression (1929–39) by commissioning murals for public buildings such as schools and hospitals, among other projects. His call resonated in the 1950s, inspiring private companies and Université Laval to commission mural works from artists. This led to the creation of several large-scale historical and thematic compositions, some of which were produced by professors from the École des beaux-arts de Québec (ÉBAQ).

Lemieux’s own work La médecine à Québec (Medicine in Quebec City), 1957, is a prime example of this muralist movement and the renewed figurative style he developed. Lemieux was commissioned by Université Laval to decorate the entrance of its newly built health sciences pavilion, where he adorned the entrance with a mural on a slightly concave surface three metres high. He chose to paint a frieze-like arrangement featuring nineteen figures connected to the medical world. Lemieux removed all traces of their individuality, reducing them, along with the background landscape, to geometric forms.

-

Jordi Bonet, Mort – Espace – Liberté (Death – Space – Freedom) or Passé, présent, future (Past, Present, Future) (detail), 1969

Three-panel mural, bas-relief in cement on metal mesh, total surface: approximately 1,200 square metres

Louis-Fréchette Hall, Grand Théâtre de Québec, Quebec City

In this mural, Bonet includes an incendiary quote by the poet Claude Péloquin: “Aren’t you sick of dying, you bunch of losers? That’s enough!” The message was intended to shake up the lethargy of the population in the peaceful capital of Quebec City, where the hold of tradition and the Church was just beginning to wane in the 1970s.

-

Jordi Bonet, Mort – Espace – Liberté (Death – Space – Freedom) or Passé, présent, future (Past, Present, Future) (detail), 1969

Three-panel mural, bas-relief in cement on metal mesh, total surface: approximately 1,200 square metres

Louis-Fréchette Hall, Grand Théâtre de Québec, Quebec City

-

Jordi Bonet, Mort – Espace – Liberté (Death – Space – Freedom) or Passé, présent, future (Past, Present, Future) (detail), 1969

Three-panel mural, bas-relief in cement on metal mesh, total surface: approximately 1,200 square metres

Louis-Fréchette Hall, Grand Théâtre de Québec, Quebec City

Mural art emerged as a key driver of artistic renewal in Quebec City, as exemplified in 1971 by a groundbreaking mural at the Grand Théâtre de Québec. Created by the Spanish-born ceramist and sculptor Jordi Bonet (1932–1979), who had made Quebec his home in 1954, the work marked a significant turning point. In this new building dedicated to the performing arts, Bonet created a monumental concrete fresco. Using the same material as the walls, he achieved a seamless integration of art and architecture. The mural spans approximately 1,200 square metres and covers the interior surface of three of the building’s four exterior walls, forming a triptych titled Mort – Espace – Liberté (Death – Space – Freedom) or Passé, présent, future (Past, Present, Future), 1969.

For three months, Bonet worked directly on the concrete surfaces, “engraving, scratching, and sculpting them” to express his immersive concept of visual creation—“a masterful improvisation aimed at bringing the material to life”—and, in doing so, to animate the walls of the theatre. The bold artistic language Bonet developed in his mural, which blends figuration, abstraction, and text, stands as a defining break with the past in the arts in Quebec City.

The Quiet Revolution gave rise to an innovative generation of artists inspired by the spirit of breaking down boundaries in contemporary artistic practices. Creators like Jocelyne Alloucherie (b.1947), Paul Béliveau (b.1954), Marcel Jean (1900–1993), Paul Lacroix (1929–2014), Richard Mill (b.1949), and René Taillefer (b.1939) explored new languages of figuration, as well as formalist and lyrical abstraction, sculpture, and installation. Trained at the ÉBAQ, these artists went on to teach at the newly established École d’art at Université Laval, which was inaugurated in 1970 by director Omer Parent in a brand-new pavilion on the Sainte-Foy campus.

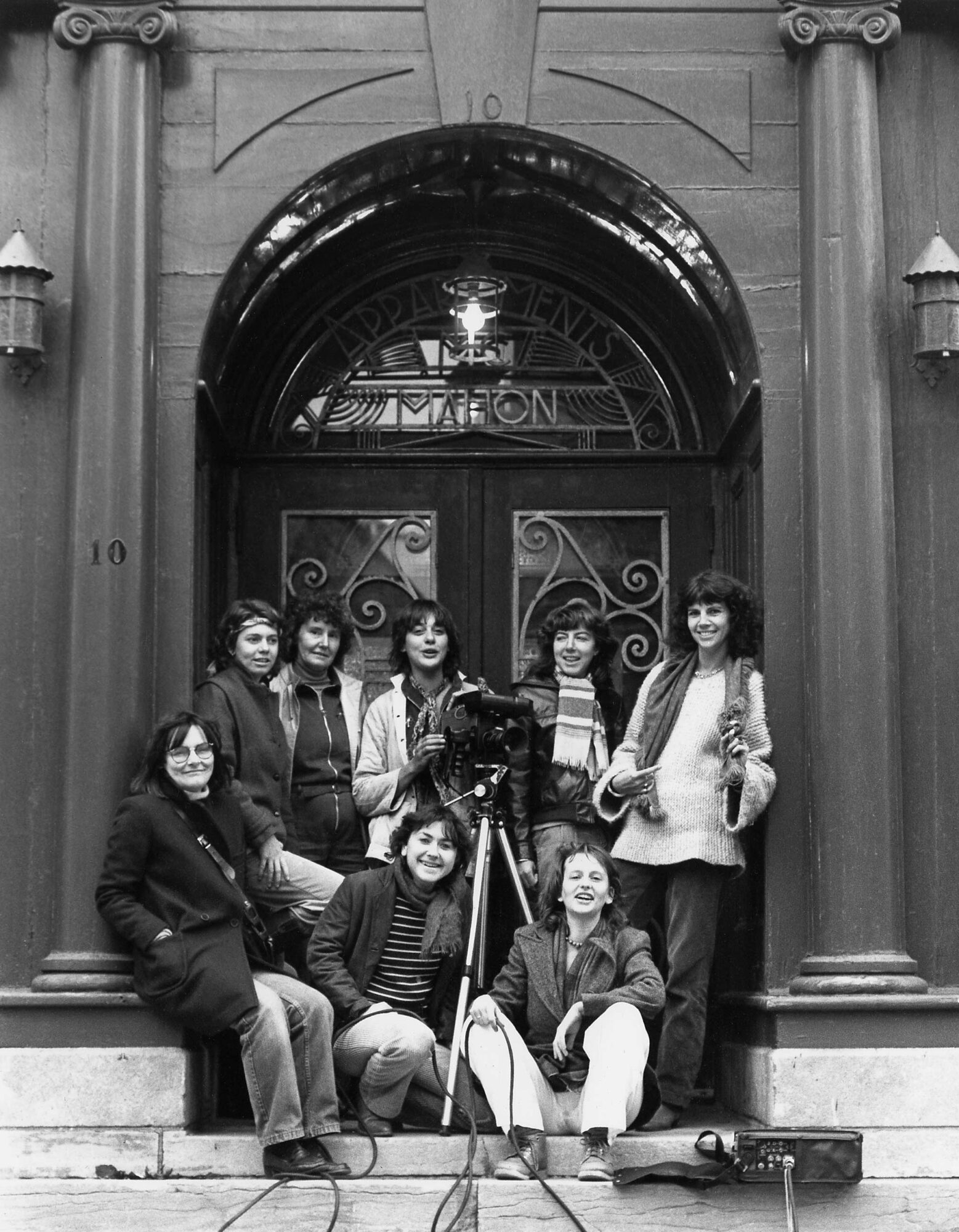

As part of this renewal of artistic practices, the feminist collective Vidéo Femmes was founded in 1973 at Université Laval by three artist-filmmakers: Hélène Roy (1941–2024), Nicole Giguère (b.1948), and Helen Doyle (b.1950). This pioneering collective developed a unique model of creation without precedent in Canada. Through film and video, the three addressed their artistic and social concerns, particularly around topics that were of interest to women and rarely discussed at the time, such as domestic violence, mental health, sexual harassment, AIDS, and incarceration. Their journey spanned more than forty years, from 1973 to 2015, and involved the production and distribution of videos and films across the city, the province, the country, and the world, including in Colombia, Argentina, Japan, and France. Their 460 works explore documentary language, formal research, and technological experimentation with video art.

In the historic Saint-Roch district of Quebec City, a remarkable creative community has thrived and gained international recognition since the late 1970s. Artists have established studios in the area and contributed to the opening of alternative galleries and artist-run centres, culminating in 1993 with the founding of the Méduse multidisciplinary complex. Dedicated to the production and dissemination of contemporary and experimental works outside the commercial art market, Méduse has become a model of creative innovation. In 2023, the artist, art historian, and sociologist Guy Sioui Durand (b.1952) co-founded Ahkwayaonhkeh, the first Wendat artist-run centre in the capital, within the Méduse complex.

These alternative spaces foster a spirit of experimentation in Quebec City. La Chambre Blanche, the first artist-run centre in Quebec City (founded in 1978), invited the sculptor Bill Vazan (b.1933) to create what was at the time his most ambitious land art piece, Pression/Présence (Pressure/Presence), 1979. Situated across from the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec), on the grass of the Battlefields Park, the large spiral, painted in white latex, symbolizes the cycles of nature and movements of celestial bodies. This project “demonstrates that a work of such scale can be achieved outside established institutions.”

This symbiosis between visual and performing arts—dance, theatre, and music—underpins exceptional careers like that of Robert Lepage (b.1957), the internationally renowned multidisciplinary artist. His monumental multimedia work Moulin à images (Image Mill), 2008–14, unveiled during the celebrations for Quebec City’s four hundredth anniversary, exemplifies this fusion of artistic languages. Through this piece, Lepage emerges as a masterful storyteller of the city’s history.

Quebec City’s vibrancy also lies in its annual and biennial events, such as Manif d’art—La biennale de Québec and Mois Multi, both launched in 2000, and both of which enjoy international acclaim. These events are largely organized by artist-run centres and museums such as the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ) and the Musée de la civilisation (founded in 1984). The MNBAQ is particularly committed to promoting contemporary art and has dedicated two sectors of its collection to it since the 1980s. Its 1989 summer exhibition, Territoires d’artistes, paysages verticaux (Artists’ Territories, Vertical Landscapes), held outside the museum walls, reflected the institution’s enthusiasm for contemporary art while using the city itself as an innovative exhibition setting. The project explored the theme of verticality within the city’s natural landscape.

Versatility, fusion, and transgression have paved the way for flexible and performative art forms embraced by emerging contemporary creators. This includes the collective BGL (active from 1996 to 2021), with their poetic installations made of recycled materials, as well as Diane Landry (b.1958) and her sound installations, Claudie Gagnon (b.1964) and her tableaux vivant, and Giorgia Volpe (b.1969) and her urban interventions. In their quest for new visual languages to reflect their reality, these artists advocate for freedom of expression, the fragmentation of artistic forms, and the dismantling of disciplinary boundaries.

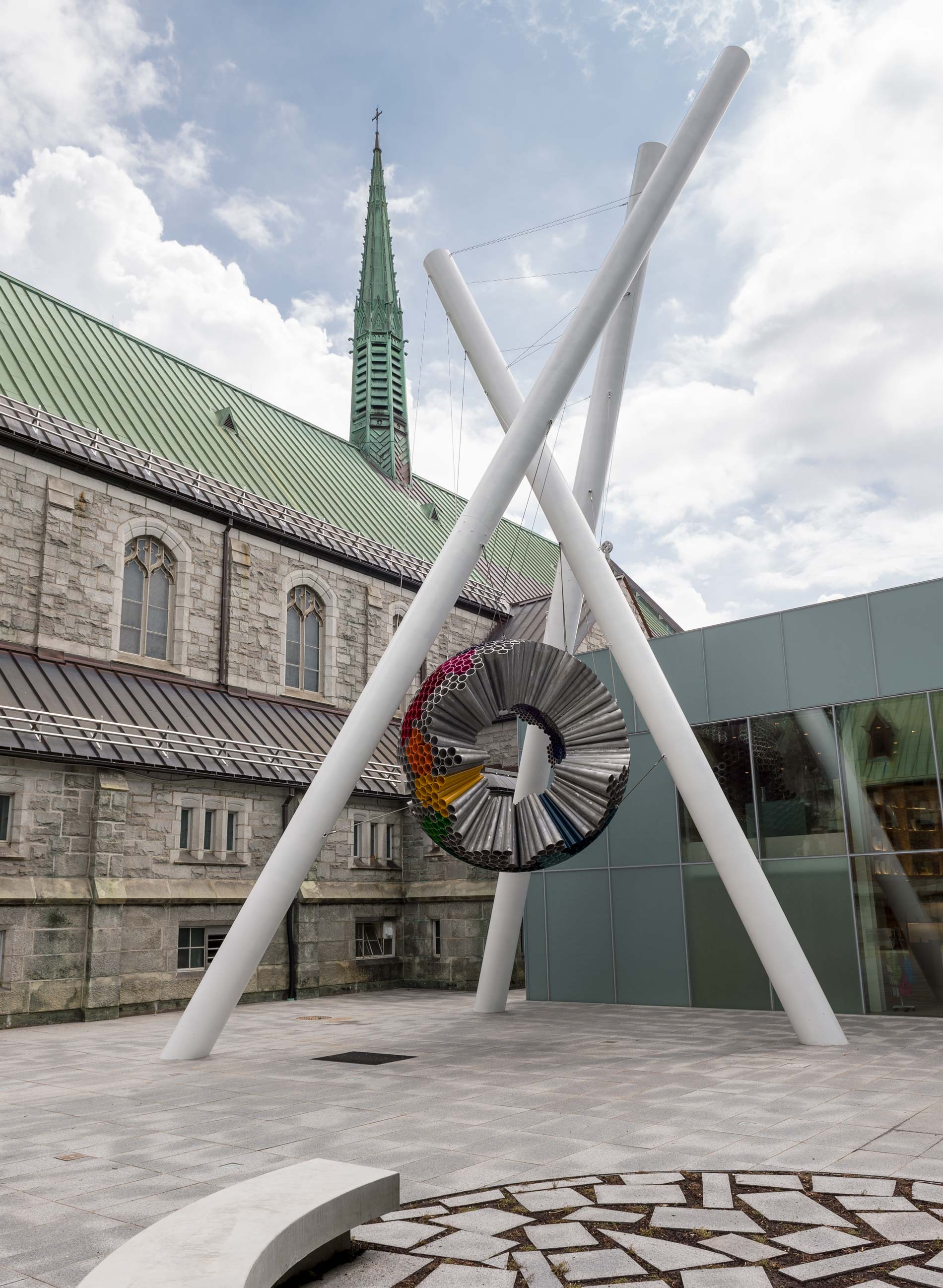

In the 2000s, as art took over urban spaces, contemporary sculptures began to appear in numerous city parks: along the Champlain Promenade by the river, around the MNBAQ, in front of the Gare du Palais, at Place Royale, and along the Saint-Charles River Linear Park. The city’s cultural revitalization project, led during the 1990s and 2000s by Mayor Jean-Paul L’Allier (1938–2016), significantly contributed to the flourishing of public art. Since the 1980s, the city’s artistic inventory has grown by more than 250 outdoor artworks, including sculptures and murals.

Today, young muralists are creating a truly unique form of urban art in unexpected locations, such as the pillars of the Dufferin-Montmorency Highway. This is made possible through events like Passages insolites (Unusual Passages), 2014–23, produced by EXMURO (founded in 2007). During this public festival, multidisciplinary art projects took over the city, transforming it into an open-air museum.

The historian and sociologist Fernand Harvey attributes the increased presence of visual arts in the collective life of Quebec City’s people to the government’s public art policy (1981), commonly known as the 1% policy. The Wendat artist Ludovic Boney (b.1981) is among those who have received commissions as a result of the program. A highly regarded creator of public artworks, Boney made the piece Une cosmologie sans genèse (A Cosmology Without Genesis), 2015, for the MNBAQ, for example. The 1% policy, which celebrates artists’ contributions to architectural and urban design, resonates strongly with other initiatives aimed at beautifying the province’s national, cultural, and tourist capital. A city where art is infused everywhere.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements