“Water is life. Mni wiconi,” the Water Protectors remind us. At the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, which began in 2016, time and history sped up; the past, present, and future bled into each other. A movement was reborn. History was unsettled and the destiny of this land contested. Before that moment of terror and jubilation, many years had passed when it seemed as if nothing had ever happened. At the Standing Rock camps, mere months felt like decades.

Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, published by the Art Canada Institute, is now available for purchase. Click here to order your copy.

But it was not the first time that history contracted and expanded. Half a century ago, when young Native activists such as LaNada War Jack and Richard Oakes arrived by boat and stepped foot on Alcatraz Island to occupy an abandoned federal prison, it seemed as if, within a matter of months, centuries had gone by. They unfurled the flag of Native liberation, around which generations of Native people have rallied. Long-held despair, anger, and dreams of freedom coalesced into the Red Power movement. Indigenous people seized their history, sometimes with weapons, other times without, but they did so according to their ancestors’ prayers and instructions. Ripples became waves: the Trail of Broken Treaties, Wounded Knee, Oka, Unist’ot’en Camp, Mauna Kea, among many other Indigenous uprisings. The history of Indigenous struggle is a counter flow against another, privileged stream of history.

The invaders first arrived by water, too—by sea, to be precise. Water is the origin story of European colonization. Yet, unlike the Genesis flood of the Old Testament, which had a beginning and an end, invasion isn’t a one-time event. Settler-colonialism is a slow-motion tsunami, unfolding over many years rather than mere moments. Today, it comes in the form of rising sea levels, the result of warming temperatures caused by capitalist development. As this tidal wave builds force, it elicits shock, awe, and horror. Its immensity is hard to comprehend. In its path are Indigenous life worlds, already displaced, if not replaced, by settler death worlds of amnesia and erasure. A wave crests, then crashes. As it ebbs, parts of the land remain submerged. The destruction is laid bare: water shaped and reshaped the earth, leaving a now-contested history in its wake.

These are the near-past and near-future dramas animating Kent Monkman’s exhibit mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, the central figure in the exhibit’s two large-format paintings, Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People, plays her familiar role as time traveller, trickster, and disrupter of historical narratives and colonial mythologies—the “natural orders” that the European wooden boat people brought with them. Colonial realism—the idea that there was and is no alternative to settler colonialism—is the genre that Monkman’s oeuvre consistently works against. This resistance flourishes and establishes its influence most in Miss Chief’s playground: the museum.

The museum upholds the colonial realism of manifest destiny, the belief that the United States was fated by God to expand across the continent. Museum works trap Native people in an imagined past that never existed, preventing them from having a future, and filtering their lives through stereotypes of savagery, nobleness, and the trope of disappearing. Miss Chief breaches manifest destiny by collecting the European curators and “Masters” to populate her world. But she does more. By assembling her army of the colonizers and the colonized, she becomes more cosmopolitan than the professed owners of the world. She puts herself into relation with the victims and perpetrators of the museum’s crimes. Miss Chief looks backwards and forwards—to a future where Indigenous people strive to live in correct relation, among themselves and a shared planet.

But museum pieces are more than just objects. They contain stories of people and place, love and desire, greed and theft. Location and history matter.

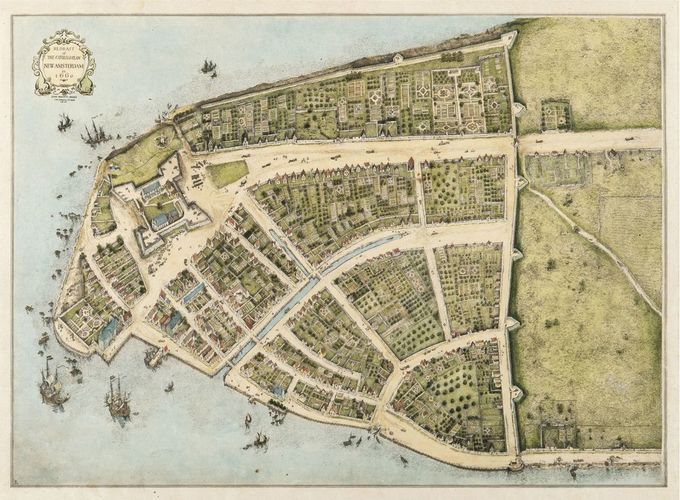

The Met is the largest museum in the United States. It is located in the same city as the centre of world capitalism, which has brought together diverse peoples through exchange and barter, the selling of property in the form of flesh, land, and money. In the seventeenth century, Dutch settlers erected a wall to fortify their colony against impending Indigenous attack on an island the Lenni Lenape people had named Manahatta. European slave masters displaced Indigenous people, and, from behind the barricade, sold kidnapped Africans. The walled market became known as Wall Street, the island as Manhattan.

Here, in a city now home to a million millionaires, the wealthy, including board members of art museums, continue to displace the racialized poor through one of the world’s most profitable real-estate markets. For every two empty New York City apartments—and, it should be noted, many of the 250,000 deserted properties are luxury condos—there is at least one person sleeping on the city’s streets, cold and hungry. Capitalism wasn’t born in Western European factories. It was born and consummated on land stolen from Natives and worked by enslaved Africans.

Printed map, color wash on paper, 31 × 40 cm, New-York Historical Society. In this redraft of the Castello Plan of New Amsterdam, Wall Street is visible on the right hand side.

In Welcoming the Newcomers, Miss Chief’s mascara runs down her tear-stained cheeks, because great tragedy and sadness birthed America. As a being that occupies both the future and the past, she mourns the present. Her outstretched hand clasps the hand of a Black man in shackles, pulling him ashore, while her other hand reaches for, possibly, an East Indian labourer wearing an exoticized turban. In the Western art canon, the European gaze creates the “Orient” or the East as much as it exaggerates and romanticizes the western frontier of the Americas.

In this peculiar equation, the colonized of South Asia and the Americas both become “Indians.” Perhaps this was Christopher Columbus’s greatest lie. Until his dying breath, he claimed to have landed in “India” and named the people of the islands “Indians.” Despite his religious, cult-like status among American-European colonists—who named the U.S. capital, and many other places, after him—Columbus never stepped foot on what is today called the United States. Yet, the European lies and misnaming persist. The British East India Company created “East Indians” in South Asia; the Dutch East India Company created the West Indies, an island chain that became home to imported East Indian labourers who supplanted both enslaved African and Caribbean-Indian labour. Elsewhere on Turtle Island, colonizers named various Indigenous peoples desert Indians, plains Indians, hostile Indians, Great Basin Indians, river Indians, good Indians, bad Indians, and red Indians.

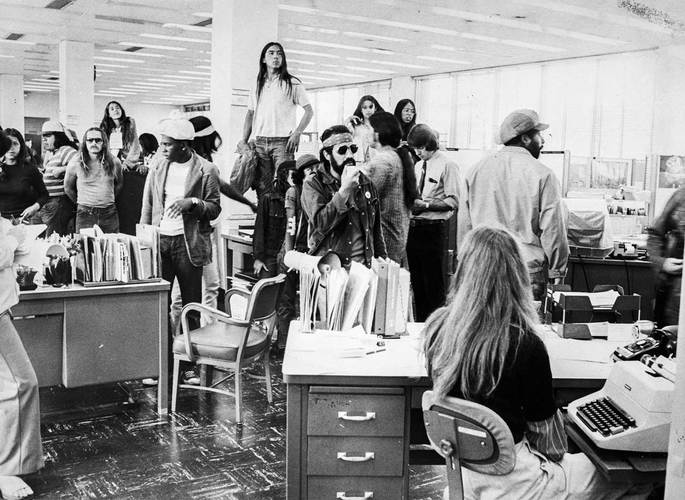

But manifestations of invasion, kidnapping, and theft are not central to Welcoming the Newcomers. Instead, Native people maintain their kinship and make new relations—even as some try to ward off colonizers with weapons. Perhaps the true founding of the U.S. originates not in Europeans lost or shipwrecked at sea but in African-Native relations and resistance. At Standing Rock, Black Lives Matter arrived en masse and organized solidarity events across the country to safeguard Native sovereignty against pipelines and police trespass. In 1972, when the American Indian Movement held a sit-in at the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters, police threatened to storm the building. A picket line of African Americans quickly assembled to form a wall between the building and the police line. Their leader, Kwame Ture, told the officers, “For y’all to get to the Native Americans, you’re going to have to go over us Africans!” There is shared blood and memory. Each act of solidarity has been a poem of resistance, with deep roots in the land itself.

The first European settlement in what is currently the United States was a profound failure, echoing into the future. In 1526, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, a Spanish conquistador, founded San Miguel de Guadalupe in the future state of South Carolina. He brought enslaved Africans and Indigenous people from the Caribbean, as well as hundreds of Spanish settlers. The Spanish slave plantation was the first settlement that tres- passed into sovereign Indigenous territory. Within a year, the enslaved had made contact with the surrounding Indigenous people, the Guales, and planned an insurrection. Africans and Natives joined together to expel the Spanish in what was the continent’s first successful anti-colonial slave revolt and Indigenous uprising. The self-emancipated Africans joined their Indigenous comrades by making kin and living with the land. Freed Africans were the first permanent non-Indigenous inhabitants of Turtle Island, not European settlers.

This rebellion and creation of a new society was one of many revolutions for freedom in the Americas. The most memorable was on the island Christopher Columbus had renamed Hispaniola, after enslaving and killing the Indigenous Arawak and Taíno people. In the late eighteenth century, on the heels of the French Revolution, Toussaint Louverture—born into slavery—led a revolt of slaves against French colonists. The outcome of the successful slave rebellion was the first free state in the Americas. The Black republic’s first ruler, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, named his military the “army of the Incas” and swore to have “avenged America” against European imperialists. To honour the deep history of African-Indigenous connections, the liberators returned the island back to its proper Taíno name: Haiti. These rebellions broke the spell of inviolability that encircled the white masters. The humble people of the Earth could rule.

Providence, Rhode Island

Right: Manuel Lopez Lopez, Desalines., 1806

Engraving, 15.2 × 11.1 cm, from Vida de J. J. Dessalines, gefe de los Negros de Santo Domingo

(Mexico: Mariano de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1806), plate following page 72, John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island

Such uprisings and their histories have been obscured by more palatable, and indeed fantastical, stories of European-Indigenous relations, such as between Pocahontas, an Indigenous child, and John Smith, an English colonist. Whereas African-Indigenous relations frequently generated revolution and revolt, European-Indigenous relations generated negotiation and capitulation. Nevertheless, in Monkman’s Welcoming the Newcomers, Indigenous beauty and life persevere in the face of the onslaught of invasion, through giving birth, and even the open embrace of potential enemies.

In Resurgence of the People, the wave of catastrophe has crashed, taking with it the colonial world and leaving Indigenous people in charge. Four white men brandishing assault rifles and body armour are trapped on an island in the distance. They represent the colonial state, stripped back to its essences of violence and exclusion. They are, variously, the military, police, border patrol, white nationalists, and mass shooters, with one man flashing the white power hand sign at the passing boat filled with Indigenous people and refugees. A white businessman desperately grasps at an oar, trying to pull his way onto the lifeboat. A Black doctor, who has just delivered a Native child, fetches the lifeless body of a nameless white man. People wearing orange life vests suggest refugees—victims of climate change and the legacy of U.S. imperialist wars in Syria, Libya, Honduras, Guatemala, and Iraq, to name but a few. Native paddlers guide the boat, suggesting Native traditions and resiliency are pushing the world towards a more sustainable and just future, in a present defined by troubled waters.

Eight white men own half our current world’s social wealth. Cheap labour is desired but not the labourers, the human beings themselves. Wealth flows to the centre of global capitalism—to places like New York City—but never outwards. And the mobility wealth provides never applies to the wretched of the Earth, forced to traverse deadly passages of water and land, across borders not of their making. If they are lucky and survive the journey, a jail cell or detention centre awaits. Their mobility is made criminal, their existence deemed illegal.

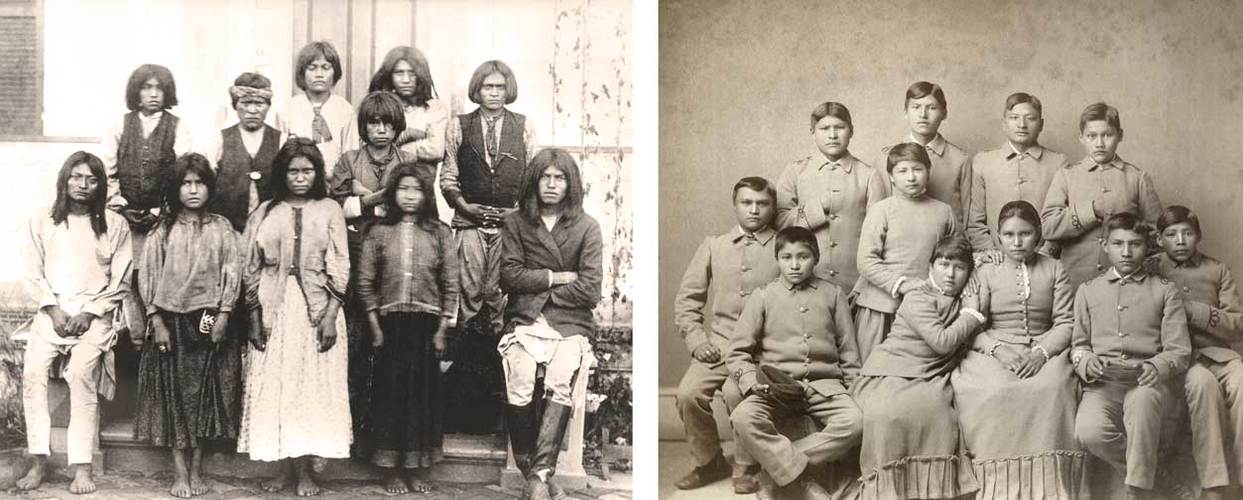

Children pay the heaviest toll for this cruelty. At the front of the boat in Resurgence of the People, Native children sit dressed in boarding school uniforms. They are the stolen generations. In Canada, thousands of Native children were removed from their families and placed in 150 boarding schools where an estimated six thousand Indigenous children died. With more than 357 boarding schools, the number of Native children who died in the U.S. is still unknown. The idea of the “modern” boarding school came from Richard Pratt, a military man. In 1874, at Fort Marion, a prison-island in Florida, Pratt drilled the Native prisoners of war with military discipline, dressed them in surplus Civil War uniforms, cut their hair, taught them English, and convinced them to become their own prison guards. In 1879, he opened the Carlisle Industrial Indian School in Pennsylvania, based on the Fort Marion experiment. Lakota children were his first students—taken hostage to force their recalcitrant parents to sell their land—and many of them died there. By 1900, more than three quarters of Native children in America were enrolled in boarding schools.

From left to right: (front row) Clement Seanilzay, Beatrice Kiahtel, Janette Pahgostatun, Margaret Y. Nadasthilah, and Frederick Eskelsejah; (second row) Humphrey Escharzay, Samson Noran, and Basil Ekarden; (third row) Hugh Chee, Bishop Eatennah, and Ernest Hogee.

Right: Chiracahua Apaches four months after their arrival at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, c.March 1887

Photographer unknown, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

From left to right: (front row, seated) Humphrey Escharzay, Beatrice Kiahtel, Janette Pahgostatun, Bishop Eatennah, and Basil Ekarden; (second row) Ernest Hogee and Margaret Y. Nadasthilah; (third row) Hugh Chee, Frederick Eskelsejah, Clement Seanilzay, and Samson Noran.

Although Carlisle closed in 1918 and the off-reservation boarding school model fell out of favour, Indian child removal didn’t end. By 1969, one of every three Native children in the United States had been adopted out to white families. And today, thousands of Indigenous children are separated from their families and put in concentration camps simply for crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Decades before Pratt, George Washington led punitive campaigns at the Carlisle Barracks against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. During the Revolutionary War, Washington set fire to more than forty Haudenosaunee towns and villages in New York State. To prevent a return to their homeland, he burned Haudenosaunee cornfields and rewarded his men with titles to Indigenous lands for their service. For his barbarism and cruelty, the Haudenosaunee called Washington “Kanatakarias”—or “Town Destroyer”—a name since bestowed upon every sitting U.S. President. And yet, Emanuel Leutze’s iconic image of Washington in the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, shows Washington as a stern patriarch—a founding father, leading this settler nation into its inglorious future. The facade is palpable. Images of Washington always show him with a clenched mouth because he wore dentures. It is now known that his “wooden teeth” were most likely made from the teeth of African slaves. To Indigenous and African people, Washington is a grisly figure, a destroyer of worlds.

45.7 × 60.3 cm, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The president and his children oversee his slaves at his Mount Vernon plantation in Virginia.

If Washington represents America, he is a counter-revolutionary force. American independence from Britain was achieved so that white settlers could take Indigenous lands west of the Appalachian Mountains and maintain the system of African slavery, which was being hotly contested in the British colonies. The settler nation’s founding document, the Declaration of Independence, claimed the King of Great Britian had “excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages.” From the beginning, slave insurrections for freedom and Indigenous nationhood were the primary enemies of this “Empire of Liberty.”

Monkman’s response to this history in Resurgence of the People is to reclaim it, replacing Washington with Miss Chief, and revealing that which has been hidden from us all. While Washington’s boat led the U.S. down the path of ruin, Miss Chief wields a prayer and an eagle feather, guiding the people towards an Indigenous future. Yet, despite her forward-looking visage, mascara once again streaks her face, as she mourns the tragedy of the history that the boat leaves in its wake. As it falls apart, the settler world is unmasked for its unreality. Its concept of enforced scarcity, for instance—carrying-capacity myths of overpopulation or fears of the “Great Replacement” of white people—is debunked by Indigenous abundance and the transformative power of healing and love. Miss Chief breaks the spell of colonial realism, showing it is nothing of the sort. The actual reality of settlers is that which has been suppressed: genocide, ecocide, theft, and destruction.

And so Miss Chief naturalizes an enduring Indigenous order—an Indigenous realism that humanizes Indigenous relations, among themselves, with other people and beings, and with the past, present, and future. She exposes the fallacies of colonial reality. Miss Chief and her cast of characters are not magical beings; they represent actual people with actual stories. Monkman resists the impulse to turn Indigenous belief and custom into mere aesthetics, or genuine political engagement into spectatorship. These paintings don’t protect us from the past, or the coming Indigenous future. They represent an Indigenous tradition of resilience and resistance. But a tradition counts for nothing if it isn’t contested or modified. An Indigenous culture that is merely preserved on museum walls is no culture at all. And no cultural object can retain its power when there are no new eyes to see it. For that reason, mistikôsiwak shouldn’t be viewed as a conversion of Indigenous practices and beliefs into lifeless artifacts, a practice typical of museums.

Put simply, Kent Monkman’s Indigenous realism becomes universal. An Indigenous future isn’t just for Indigenous people—it is essential for the very existence of life on the planet. This future calls for a complete departure from the current unreality represented in art. And the Indigenous generosity in Monkman’s work should not be read as weakness, but rather strength—a call for a better world that starts with more humane art.

Last Indigenous Peoples’ Day, outside The Met, marchers with the movement and activist collective Decolonize This Place chanted, “They want art but not the people.” It was a challenge to institutions like The Met, one also represented by mistikôsiwak. At a time when the state is stripped back to core military and police functions, with concentration camps and the world’s largest prison co-existing beside Starbucks, strip malls, and art museums, it’s clear that capitalism is not opposed to authoritarianism; in fact, it embraces it. What does art do for the people? mistikôsiwak is a declaration that art alone cannot solve longstanding colonial inequalities. Buying the right products or collecting the right art will not put an end to colonialism. Monkman’s engagement is much deeper—bleeding off the canvas and onto the streets, into the reservations of our minds and hearts. Monkman forces each one of us to witness the real, while demanding we undo the unreal. The act washes over us like waves of history, ebbing and flowing, oscillating between love and rage. It hurts and heals. Water is life.

From April 2016 until February 2017, Indigenous activists and water protectors engaged in a direct action to block the expansion of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Three camps were set up that housed between three thousand to four thousand people.

Nick Estes is a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. He is an assistant professor in American Studies at the University of New Mexico. In 2014, he co-founded The Red Nation, an Indigenous resistance organization. Estes is the author of the book Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019).

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix