When Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986), an émigré from Russia via Paris, arrived in Toronto in 1931, the local art scene was ready for a change. The dominant wilderness landscape idiom, rooted in nationalist ideology, was no longer adequate to express the social and political turmoil that would unfold over the next two decades. Clark brought her knowledge of European art and an intuitive socialism to the work she produced in her new home. But the catalyst that made her start painting socially charged works was a chance meeting in 1936 with the Canadian physician Norman Bethune (1890–1939), who served as a frontline surgeon during the Spanish Civil War.

The following year, 1937, proved to be a significant one in Clark’s artistic development. Clark was elected a member of the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour, the group she exhibited with most often. She was already known for her landscape and still-life paintings, but from this point on she began to address socially relevant subjects in her work, influenced by contemporary events—the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War—and by Dr. Bethune.

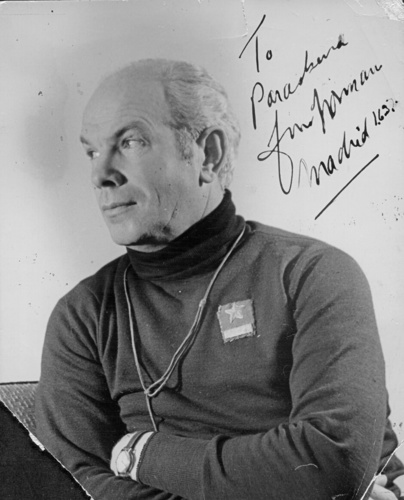

A signed photograph sent to Paraskeva Clark from Dr. Norman Bethune,

with the inscription: “To Paraskeva from Norman, Madrid 1937”

In the summer of 1936, Bethune was in Toronto to raise money to send medical aid to the Republican army in the Spanish Civil War. He, Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), and Pegi Nicol (1904–1949) crashed a dinner party at the Clarks’ one evening—with profound implications for the artist. Up to that point, she had not been politically minded, but Bethune, who had recently become a Communist and had visited Leningrad the year before, likely encouraged her to become actively involved in the Spanish Republican cause.

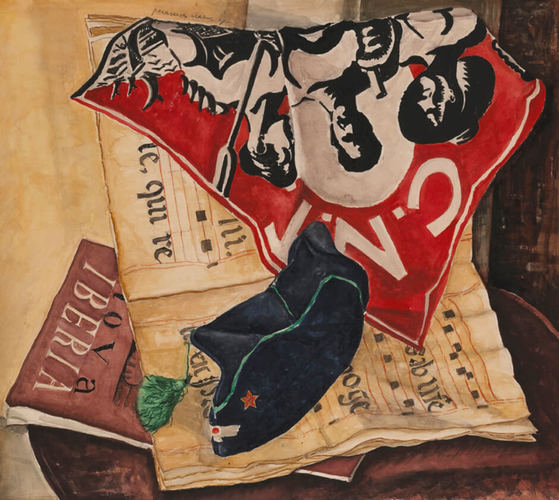

As a result of meeting the charismatic Bethune, with whom she had a brief affair, Clark embarked on works based on her memories of Russia. She also exhibited her first work with political content, Presents from Madrid, 1937, a watercolour depicting the small mementoes from the war that Bethune sent her in correspondence from Spain. In April, she wrote an article in the left-wing journal New Frontier advocating a role for the artist in society and countering a piece by Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966), published earlier in Canadian Forum, arguing that artists could ignore social and political affairs.

Watercolour over graphite on wove paper, 51.5 x 62 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In the summer of 1937, Clark produced her second painting with political content, Petroushka, 1937. She considered this canvas to be her most important work and sent it to the Great Lakes Exhibition (1938–39) and the CGP section of the New York World’s Fair (1939–40), where it would be seen by larger American audiences. Petroushka is a piece of strong social commentary whose source is veiled. It brings together Clark’s childhood memories of puppet theatre in the streets of Saint Petersburg and her response to a violent clash between police and striking steelworkers in Chicago, in which five workers were killed.

Oil on canvas, 122.4 x 81.9 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Clark taped the article (“Five Steel Strikers Killed in Clash with Chicago Police,” Toronto Daily Star, June 1, 1937) to the back of the canvas to document the source. She transformed the story of Petroushka (the Russian equivalent of Punch or Pulchinello) to describe the plight of the worker, subjugated by the interests of capitalism (the banker) and its enforcers (the policeman). The viewer looks down on the scene in a cobblestoned yard between apartment blocks. The crowd responds to the performance with catcalls and clenched fists—an anti-fascist symbol of unity, strength, and resistance used here to indicate the artist’s support for their cause. Two preparatory sketches, including Study for Petroushka, 1937, illustrate the evolution of the painting.

Watercolour on beige cardstock, 32.2 x 20.6 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

In the closing years of the decade, Clark worked for the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy and tried (unsuccessfully) to bring Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) Guernica, 1937, to Toronto in 1939 as a fundraising initiative to assist Spanish refugees. Clark did not produce a large number of paintings with social purpose during her career, yet they are her best-known works today.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans