The greatest misfortune of Pitseolak Ashoona (1904-1983)—when she was left widowed to raise her young children—provided the catalyst that led her to become one of Canada’s most important artists. As she described the time: “After my husband died I felt very alone and unwanted; making prints is what has made me happiest since he died.” Despite the impact of the years of hardship that followed his death, scenes of deprivation or suffering almost never appear in her drawings, though certain images convey sadness and longing at his passing. Pitseolak was the one of the first Inuit artists to create openly autobiographical work, yet she focused almost completely on good memories and experiences.

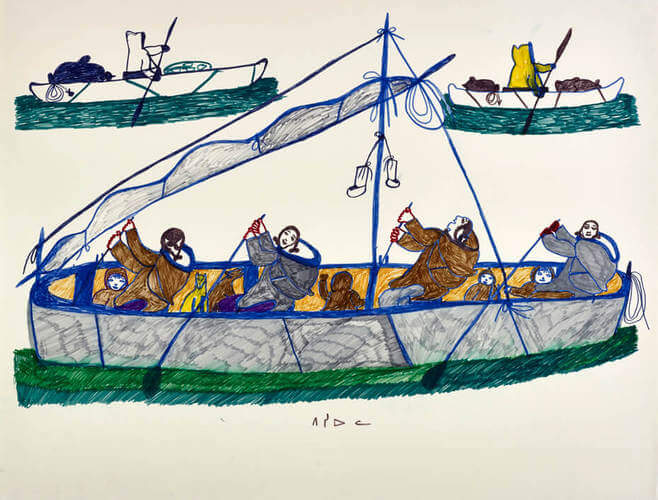

Coloured felt-tip pen on paper, 50.7 x 66.3 cm, Collection of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative Ltd., on loan to the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario

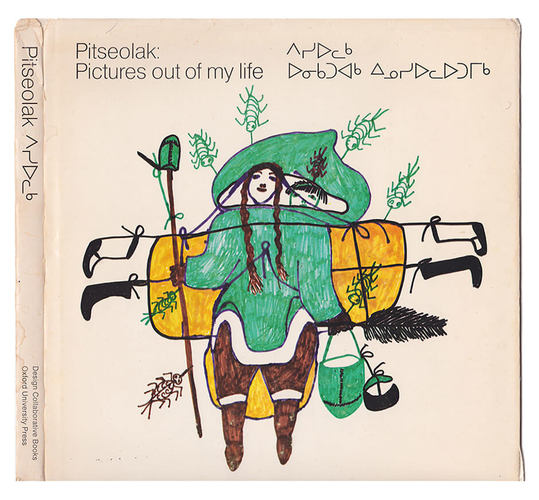

Pitseolak had “an unusual life, being born in a skin tent and living to hear on the radio that two men landed on the moon,” as she recounts in her biography Pictures Out of My Life. Born in the first decade of the twentieth century, she lived in semi-nomadic hunting camps throughout southern Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island) until the late 1950s when she moved to the Kinngait (Cape Dorset) area, settling in the town soon thereafter. In Cape Dorset she taught herself to draw and was an active contributor to the annual print collection. By the 1970s she was a world-famous artist, with work exhibited across North America and in Europe. She died in 1983, still at the height of her powers.

In the 1940s and 1950s an Inuit widow, particularly with young children, would have remarried to maintain the complementary gender-related roles necessary for survival. It is unusual that Pitseolak never did and even more remarkable that she was able to eventually provide for her family by making art. Her opportunity came with an arts and crafts program initiated in Cape Dorset by the department of Northern Affairs and National Resources (Indian Affairs and Northern Development after 1966) as an economic incentive for Inuit who were making the transition from subsistence hunting and trapping to a wage economy in settled communities.

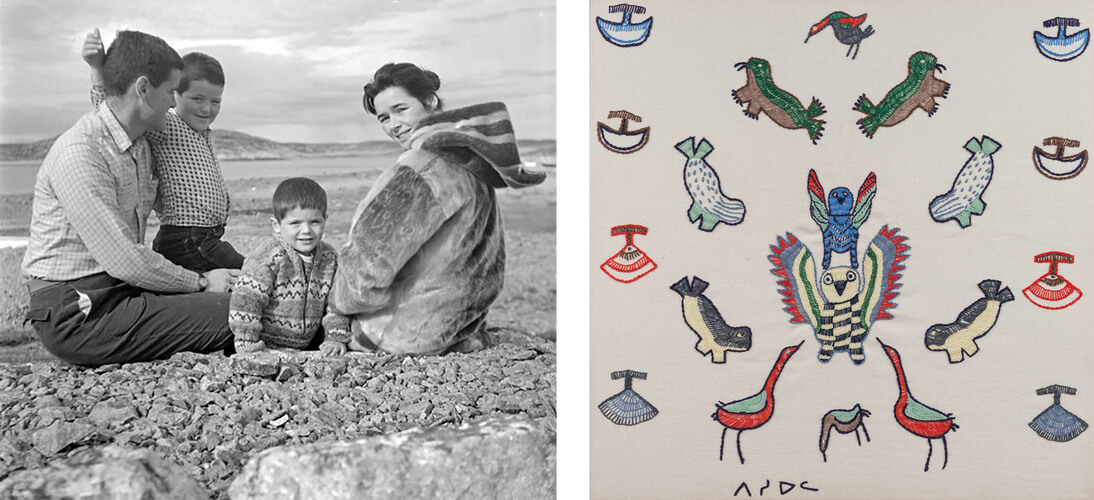

The artist James Houston (1921–2005) and his wife, Alma Houston (1926–1997), were instrumental in developing the program. James Houston first travelled to the Arctic in the late 1940s and returned to Montreal with a collection of small Inuit carvings. Encouraged by the Canadian Handicrafts Guild and grants from the federal government, the Houstons moved to Cape Dorset in 1956 to work with the Inuit. Although Inuit had carved small objects, usually in sea ivory, as a pastime for centuries, there was no precedent for drawing images on paper or printmaking, or for the notion of the artist as a role within the community. James Houston devoted his efforts to the introduction of printmaking and stone sculpting. Alma focused on the traditional skills of Inuit women and explored the potential for hand-sewn goods.

James, John, Samuel, and Alma Houston in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, 1960

Photograph by Rosemary Gilliat Eaton

Pitseolak Ashoona, Untitled, c. 1960

Embroidery on stroud, 67 x 67 cm, private collection

The sewing that Pitseolak had done throughout her life creating garments for her family led her to work with Alma Houston on clothing production for sale in the developing market for Inuit arts and crafts. For two years Pitseolak made finely decorated parkas, mittens, and other items that were sold through the newly formed West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. However, after seeing the drawings and prints created by her elder cousin Kiakshuk (1886–1966), and intrigued by the possibility of making a better income, Pitseolak decided to try drawing. As she would later explain:

I started drawing after other people around here had already started. Nobody asked me to draw. Because my son’s wife died when their two children were very young, his children used to be with me. One night, I was thinking, “Maybe if I draw, I can get them some things that they need.” The papers were small then, and I drew three pages of paper. The next day I took them to the Co-op, and I gave them to Saumik, and Saumik gave me $20 for those drawings.… Because for my first drawings I got money, I realized I could get money for them. Ever since then, I have been drawing.

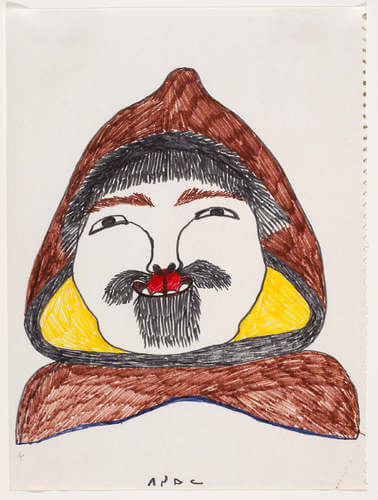

A common perception of Inuit art from Pitseolak’s era is that the artists did not represent themselves or their families or events from their own lives. During her first decade as an artist, Pitseolak had a reputation for depicting the “old ways”; although her work was culturally specific and accurate, there was no expectation that she was referring to personal experience. With the publication of Pictures Out of My Life in 1971, her drawings were recognized for the first time for their autobiographical content. Her works including The Critic, about 1963, Portrait of Ashoona, about 1970, and Memories of Childbirth, 1976 are all based on stories from her life. By the end of Pitseolak’s life her reputation for this content was firmly established.

Coloured felt-tip pen on paper, 27.6 x 20.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans