During his eleven years in New France as a Jesuit missionary priest, from 1664 to 1675, Louis Nicolas (1634–post 1700) travelled extensively. It appears, though, that his main interest was not to convert souls to the Catholic faith but to create art that documented the natural history of this land by observing the local inhabitants, plants, animals, birds, insects, and fish he encountered.

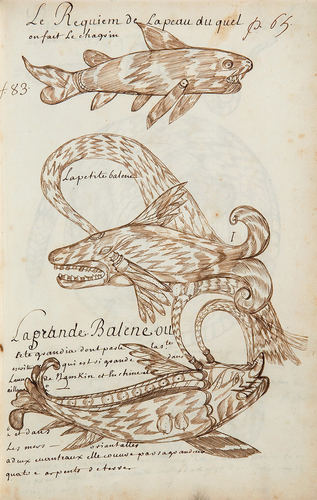

The Codex Canadensis, an illustrated manuscript by Nicolas, ranks as one of the most significant documents of the late seventeenth century in North America—a work of art that is also an example of graphic scientific reporting. All told, the seventy-nine-page Codex is illustrated with 180 pen-and-ink drawings on paper, including some with watercolour (or perhaps tempera) tinting.

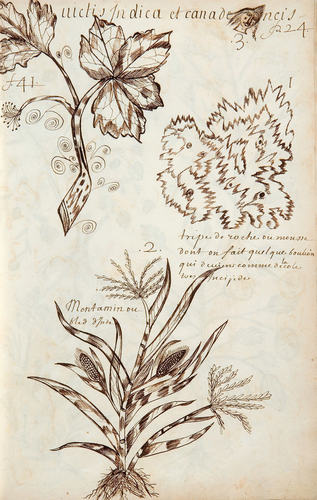

Louis Nicolas, Tripe de Roche, or Moss (Tripe de roche ou mousse), Codex Canadensis, page 24, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

The Codex is an unparalleled creation of its time, a work of art rare in quality and in its depictions of plants and animals. The details Nicolas provides are far greater and more reliable than those in the writings of explorers such as Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain or governor Pierre Boucher, author of A True and Natural History of the Customs and Productions of the Country of New France Vulgarly Called Canada (Histoire véritable et naturelle des moeurs et productions du pays de la Nouvelle-France vulgairement dite le Canada) (1664). Pictorial representations from New France in the 1600s are extremely rare. For that reason alone, the detailed and accurate images of the plants and animals that Louis Nicolas created in the Codex Canadensis are invaluable.

Louis Nicolas, The Shark, from Whose Skin Shagreen Is Made (Le Requiem de la peau du quel on fait le chagrin), Codex Canadensis, page 65, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Nicolas lived before the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), who formalized the modern classification system of naming organisms. He therefore organized his illustrations according to the hierarchy he had learned during his Jesuit education: first the humans, the highest beings in the natural order; then plants, animals, fish, birds; and finally, a few images recording the French arrival in North America and some domestic animals they brought with them. Nicolas claimed that he had seen every specimen he drew (even though he included a unicorn amongst his animals).

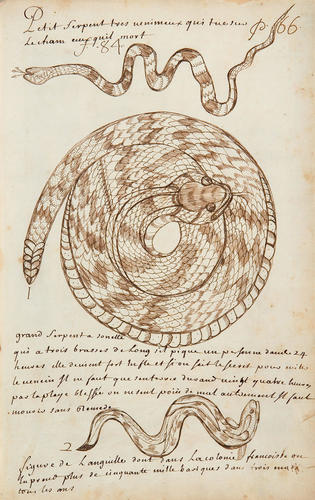

Louis Nicolas, Small, Very Poisonous Snake That Kills Immediately Those That It Bites (Petit serpent tres venimeux qui tue sur le cham ceux quil mort), Codex Canadensis, page 66, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Nicolas’s approach fits with the religious, anthropocentric view of nature that was prevalent during his lifetime, in which all has been made by God as a resource for humanity. For instance, the glands of the beaver (the castoreum) are seen as producing a substance that is useful to people rather than for marking the animal’s territory. His illustration of a rattlesnake includes instructions about how to treat a bite, and of the eel featured on the same page, Nicolas tells readers, “more than fifty thousand barrels of them are caught in three months every year.” He valued the pharmaceutical properties of certain plants and illustrated their roots, fruits, and flowers—for example the edible roots of the broadleaf arrowhead (ounonnata), which were used extensively by Indigenous peoples.

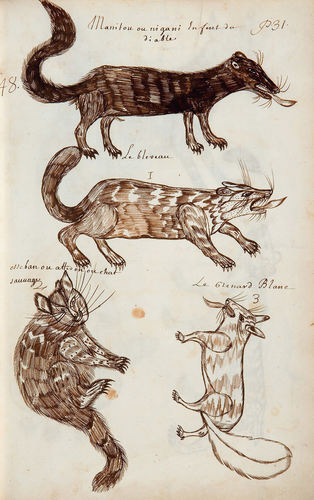

Louis Nicolas, Manitou or Nigani, Devil’s Child (Manitou ou nigani Enfant du diable), Codex Canadensis, page 31, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Nicolas’s animal images are often astonishing for their realism and individuality, and he depicted them from different angles and in varied poses—standing, eating, lying down. Many artists of his period had the opportunity to see only dead animals, and they portrayed them with stiff bodies and their tongues hanging out: the prolific Swiss natural scientist Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) drew his beaver that way, and Nicolas followed suit in the Codex.

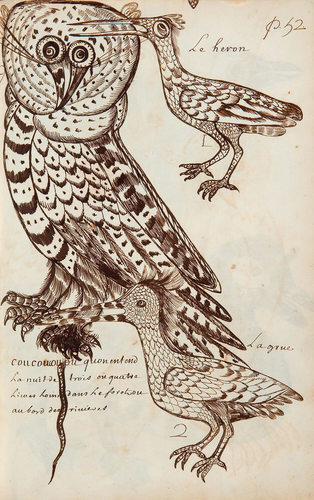

Louis Nicolas, Coucoucouou, Codex Canadensis, page 52, n.d.

Ink on paper, 33.7 x 21.6 cm, Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Among the most accurate and endearing images in the Codex are its birds. Nicolas drew most of them in ink only, using cross-hatching and short straight or shaped strokes effectively to catch the effect of feathers, plumed heads, and clawed feet, but some are highly coloured. The page showing owls is particularly fine. Many of these bird drawings are also remarkably accurate. At a meeting of the Society of Canadian Ornithologists in Saskatoon in October 2003, members were shown a reproduction of the opening page of the bird images in the Codex (the hummingbird, red finch, American ortolan, and others) and they easily identified the species without reading the captions.

This Essay is excerpted from Louis Nicolas: Life & Work by François-Marc Gagnon.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans