Music had a deep influence on Montreal painter Yves Gaucher (1934–2000). In an interview from 1996, he recalled, “It was only in music that I came to understand what a profound aesthetic experience really was. I heard concerts that marked me, that opened my ears and eyes. A very strong sensorial experience. Then in my work, I sought to recreate this experience which made me forget time, space, physicality.” Throughout his life Gaucher retained a deep commitment to jazz, Indian music, and contemporary classical music.

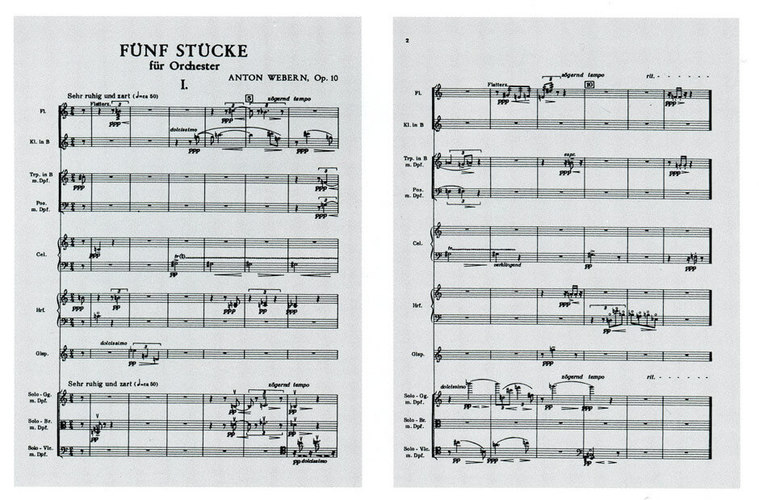

Musical score for Anton Webern’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, op. 10, first movement.

Gaucher described rhythm, in the context of both life and art, as the basis of aesthetic experience. During his first visit to Paris in 1962, he attended a concert of music by Pierre Boulez, Edgard Varèse, and Anton Webern. It was Webern’s music that most profoundly disturbed him and challenged the basic preconceptions that heretofore had driven his artistic expression. As he recalled: “The music seemed to send little cells of sound into space, where they expanded and took on a whole new quality and dimension of their own.”

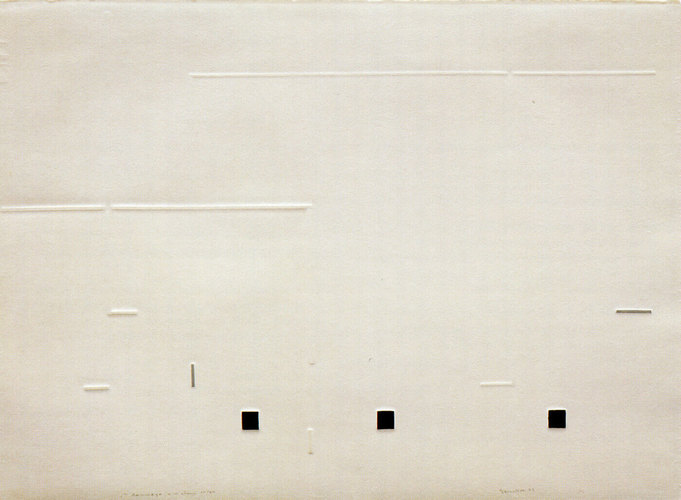

Yves Gaucher, In Homage to Webern No. 1 (En hommage à Webern n° 1), 1963

Relief print in black and grey on laminated paper, 57 x 76.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

The experience provoked a crisis and an intense period of work, leading Gaucher to create the series of prints entitled In Homage to Webern. For a long time he experimented with drawings until he arrived at a dynamic formal solution in which the composer’s “cells of sound” found their visual equivalents in the “signals,” the system of pure notations of lines, squares, and dashes that he disperses across his paper sheets. It is not that Gaucher is illustrating music that he had heard; rather, it is as if in his mind’s eye Gaucher had envisaged visual equivalents for Webern’s aural sensations as they dispersed themselves in the space of hearing.

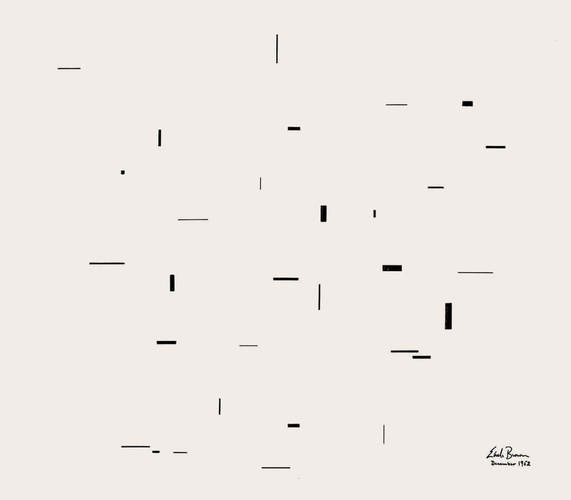

Graphic score for Earle Brown’s December 1952.

Also of note are the close visual analogies between Gaucher’s prints and the graphic score for December 1952, by the American composer Earle Brown. Brown invented and used various innovative musical notations: his score for December 1952 is made up entirely of points and horizontal and vertical dashes of different shapes and sizes, separated in space and spread out over the page. Brown’s score shares the Webern prints’ non-centred dispersal of their symbols in such a way, as the musicologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez describes it, that it “invites the performer to play the different elements in random succession and therefore escape from the linear constraints of a ‘normal’ score.”

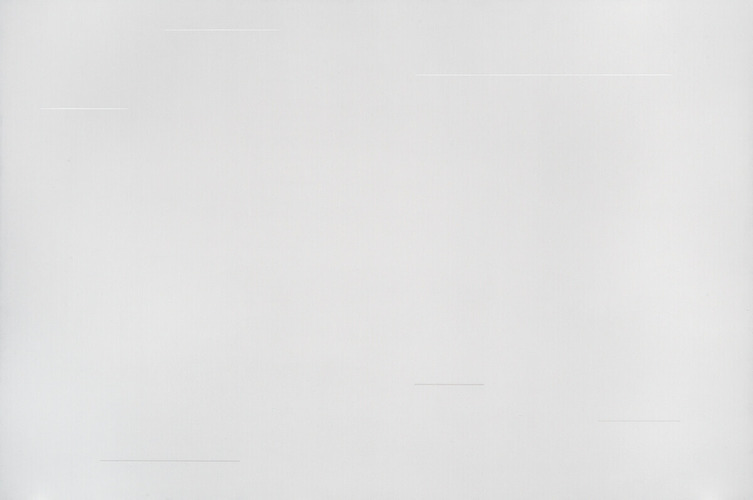

Yves Gaucher, Untitled (JN-J1 68 G-1), 1968

Acrylic on canvas, 203.8 x 305.3 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery

Gaucher had also begun to listen to Indian music sometime around the beginning of the 1960s, in conjunction with reading Indian philosophy. He described the Indian raga as another of the strongest musical experiences he had experienced, valuing it for its constructive discipline. In the concerts of Ali Akbar Khan, his favourite performer, however, the results became “free and creative,” until listening intensified into an “ecstatic experience.”

Gaucher, nevertheless, despite his passion for music, became cautionary when people started to describe him as “a musical painter.” He had originally used musical titles because, as he said, “I felt they were more abstract, and it backfired.” By 1967, therefore, he largely abandoned titles, substituting letter and number combinations, such as JN-J1 68 G-1, 1968, that would be meaningless except to himself, for whom they served as codes to identify the colours he had used in each painting, for reference, in case of future repair work.

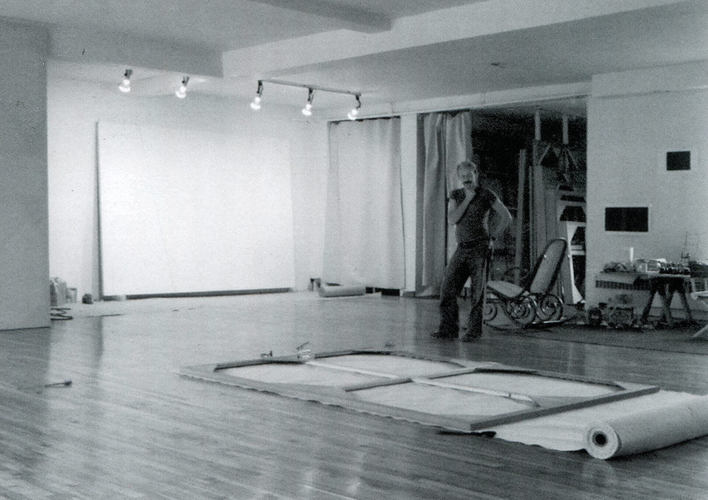

Gaucher in his studio on De Bullion Street, Montreal, 1979.

In 1968, as a guest artist, he joined the graduate program in electronic music at McGill University, intrigued by, among other things, the electronic equipment that could read drawings and translate them into music, and vice versa. But he found the exercises finally meaningless, reinforcing his dictum that “true art should be a purely visual language, just as music is a purely auditive [sic] language…. Art must speak only to the eyes, and to nothing else, to reach the soul.”

This Essay is excerpted from Yves Gaucher: Life & Work by Roald Nasgaard.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

The Rule of Chance

Jean Paul Riopelle’s break with Automatism

By François-Marc Gagnon

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans