The Montreal artist Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) began his career as a full participant in the Quebec Automatiste movement. He contributed to the group’s manifesto Refus global, released on August 9, 1948, insisting that its text not be a repetition of similar European declarations such as the Surrealist movement’s Rupture inaugurale, which he had also signed in 1947 alongside André Breton (1896–1966).

Riopelle defended the scandalous Refus after its historic publication, and his abstract works at the time were in harmony with the intentions of his fellow Automatistes, including Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and Marcel Barbeau (1925–2016). Collectively they called for a rejection of figuration in favour of the spontaneous, instinctive creative act. In Riopelle’s Hochelaga, for instance, touches of colour are distributed over the entire surface, which is strewn with drips that suggest a speedy execution and a lack of conscious control.

Perron, Maurice, Second collective Exhibition of the Automatistes at the Gauvreau home, 75 Sherbrooke Street West, February 1947

Black-and-white negative, 6.5 x 11 cm, collection of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Maurice Perron fonds (P35.S7.Pd), © Courtesy of Line-Sylvie Perron

However, by the early 1950s, Riopelle had begun to break away from the movement. In an automatist work of art, the artist maintains control even though he or she might use coincidental elements to create the composition. This bothered Riopelle, who was in search of an art that removed any type of control and allowed for free creation. He found the work of his compatriots, such as Borduas and Barbeau, limited in this regard. They restricted the opportunity for accidental elements to invade the composition of a painting.

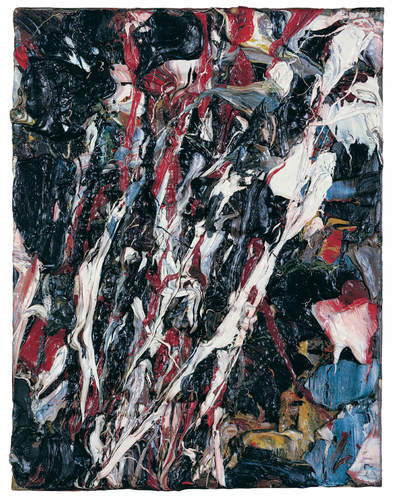

Jean Paul Riopelle, Hochelaga, 1947

Oil on canvas, 60 x 73 cm, © Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019), Power Corporation of Canada Art Collection, Montreal

For instance, Borduas painted Nature’s Parachutes (19.47) in two stages: first the dark background, then, once the paint had dried, the “objects” (the “parachutes”), carefully placed to avoid any overlapping. The Montreal artist Guido Molinari (1933–2004) suggested that this composition would have been impossible if Borduas had proceeded with his eyes closed. Yet Borduas claimed to have no preconceptions of what his painting would become: “faced with the white page, my mind free of any literary ideas, I respond to my first impulse. If I feel like placing my charcoal in the middle of the page, or to one side, I do so without question, and then go on from there.” Despite his assertion, it is difficult to see how any element of the whole could be moved without compromising the balance of the composition. Something similar can be said of Barbeau’s painting Tumult with a Tense Jaw, in which the artist oriented his marks in a V shape, its ends pointing to the upper left and right corners of the pictorial surface. It seems that here, too, a “restriction of chance” occurs.

![Paul?Émile Borduas, Nature’s Parachutes (19.47) (Parachutes végétaux [19.47]), 1947](/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/the-essay_54_paul-emile-borduas-1947-ou-parachutes-vegetaux-contextual-article-image.jpg)

Paul-Émile Borduas, Nature’s Parachutes (19.47) (Parachutes végétaux [19.47]), 1947

Oil on canvas, 81.8 x 109.7 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, © Estate of Paul-Émile Borduas / SOCAN (2019)

At the Paris exhibition Véhémences confrontées (Confronted Vehemences) at La Dragonne, also known as the Galerie Nina Dausset, which ran from March 8 to 31, 1951, Riopelle joined several other artists in releasing a written statement that outlined their dissenting position against the movement: “Automatism, which was meant to achieve total openness, has shown itself to be limited by the action of chance. . . . A painter who draws involuntarily can only repeat indefinitely the same curve; nothing allows us to prefer this act to one restricted by the kind of tool an architect might use to draw a curve. Only total chance is fertile.”

Marcel Barbeau, Tumult with a Tense Jaw (Tumulte à la mâchoire crispée), 1946

Oil on canvas, 76.8 x 89.3 cm, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal

Ironically, while Riopelle spoke out against automatism in Paris, his contribution to Véhémences confrontées, Untitled, embodies the movement’s desire for “total chance.” Following the showing of this painting, however, he withdrew from the group altogether, which he felt had betrayed him because they claimed a “total openness” that nonetheless restricted opportunities for true spontaneity to occur.

Ultimately, Riopelle could not accept automatism as a “refusal of conscious intent” and found it to be a principle that resulted only in constraint. “The important thing is intensity,” he observed, and to maintain a “state of purity, of availability before the work.” Anything less would lead to monotonous and repetitive work—a “dead end,” he declared.

Jean Paul Riopelle, Untitled (Sans titre), 1949–50

Oil on canvas, 35 x 27 cm, © Jean Paul Riopelle Estate / SOCAN (2019), private collection

This Essay is excerpted from Jean Paul Riopelle: Life & Work by François-Marc Gagnon.

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

Karen Tam’s Autumn Tigers

Bridging Past and Present: Invisible Made Visible

By Imogene L. Lim, PhD

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

The Frontier Portraits of C.D. Hoy

A Chinese Canadian Photographer’s Tribute to His Community

By Faith Moosang

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

Interrogating Identity

Suzy Lake explores the role of photography in shaping how we understand and see ourselves

By Erin Silver

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

An Emboldened Artist

How Oviloo Tunnillie achieved rare international acclaim as an Inuit female sculptor

By Darlene Coward Wight

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Painting the Cultural Mosaic

William Kurelek traversed the country in a quest to capture its diverse inhabitants

By Andrew Kear

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

Domestic Discontent

Mary Pratt’s poetic scenes of home life are praised for their political edge

By Ray Cronin

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

A New Vision of the North

Annie Pootoogook’s art offers unprecedented insights into the contemporary Arctic

By Nancy G. Campbell

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Meetings of Minds

Sorel Etrog found new ideas in collaborative work

By Alma Mikulinsky

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

Introducing Miss Chief

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Shirley Madill

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

A Practice of Recovery

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Sasha Suda

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

Decolonizing History Painting

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Ruth B. Phillips and Mark Salber Phillips

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

A Vision for the Future

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Nick Estes

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

Inside Kent Monkman’s Studio

An excerpt from the ACI’s book “Revision and Resistance”

By Jami C. Powell

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

From Taos to New York

Agnes Martin and the currents of American Art

By Christopher Régimbal

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

An Artist Blooms

Mary Hiester Reid’s floral aesthetics

By Andrea Terry

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

The Patriotic Painter

Greg Curnoe’s Canada

By Judith Rodger

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

Walking, Stacking, Dancing

Françoise Sullivan’s conceptual 1970s

By Annie Gérin

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

The Extraordinary North

Tom Thomson’s diary of landscape

By David P. Silcox

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

A Champion of Abstraction

Jock Macdonald sought a new expression in art

By Joyce Zemans

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix

Defiant Spirit

Quebecois artist Ozias Leduc drew on Europe but created a Canadian ideal

By Laurier Lacroix