Too often, accounts of North American history begin with the arrival of European settlers. Indigenous peoples, our claims to the land, and our histories are erased from the narrative. This is true within education systems, popular media, and certainly large-scale institutional museums and galleries. Through mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People), Kent Monkman appropriates this conventional narrative and recentres a shared, more nuanced history of North America—understanding and recognizing the contributions, generosity, and ways of knowing of Indigenous peoples. Moreover, Monkman imagines a kind of future history where Indigenous peoples and values provide hope and leadership for all of us as we navigate crises both North American and global in scope.

Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, published by the Art Canada Institute, is now available for purchase [en anglais seulement]. Click here to order your copy.

I spent time with Monkman in his Toronto studio as he neared completion on the two paintings that comprise his exhibit: Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People. We talked about the creation of the paintings, his studio process, and how mistikôsiwak fits within his larger body of work. Drawing from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection of European, American, and North American Indigenous works, Monkman’s diptych is a visually stunning narrative that conveys the multiplicity and complexity of colonial interactions and exchanges. His practice exemplifies what I and other post-colonial and Indigenous scholars have referred to as colonial entanglement, a concept that grapples simultaneously with the uneven power relations at play within colonialism, and with the agency of Indigenous peoples and nations within these relations.[1] Monkman has appropriated the colonizers’s tools—most notably Western artistic traditions such as history painting and the atelier model—and translated them into forms that are meaningful and relevant within his own practice and communities. In doing so, he reimagines Western art as a method of empowerment, used to build and strengthen Indigenous futures. Through this reimagining, Monkman’s mistikôsiwak moves beyond a simple retelling of our shared history to create a shared intellectual space that encompasses many perspectives and interpretations.

JP: What does it mean for you to have a work on view at The Met?

KM: This is an opportunity to extend my practice into a museum… [which] has a strong relationship with its own history and with art from around the world.

The Met is a world-culture museum, and I like to make connections with settler artworks, European artworks, and Indigenous artworks, and create a dialogue about cultures and histories that are shared and also quite different.

JP: Thinking about Welcoming the Newcomers and Resurgence of the People, their scale and the layers of meaning embedded within each of the characters, I’m somewhat overwhelmed. Where do you start?

KM: Basically, when I take on a project like this, I do research first within the collection… with an open mind. Then I focus in order to find works that fit certain ideas. I start to think about how to reference these works in the new composition that might trigger dialogue with the originals in the collection. The next stage is to do a small pencil sketch. From that sketch, I bring in my team and we begin to identify who all the characters are. We come up with a list, and then we cast for a photo shoot.

JP: How do you select the models?

KM: We look for models who fit that character, whether it is a body type or a particular ethnicity. Often the hair doesn’t matter to me; I just repaint it anyway. If we’re looking for Indigenous people, we cast Indigenous people. We also try to get the best actors we can, for expression and emotion. Sometimes we don’t get exactly what we want in our models, but photography is only a stage.

Once the models are cast, the costumes are designed. Next, we bring the models in, and I arrange them in the poses that I want. We pay close attention to the lighting. After we get our digital photographs, all of that source imagery is composited in Photoshop. That is translated into a smaller-scale study where I start to pull all of the elements together in the painting, working with lights and darks and shadows, situating every character into three-dimensional or at least the illusion of three-dimensional space. We then commence the larger version.

JP: In terms of the painters you’re working with at the studio, is there a standard process?

KM: It depends on their skill level. I’ve recreated an atelier based on a classical model where I work with apprentices and younger artists. They’re trained in my technique and style. We work with their strengths. Someone might be extremely good at detail, and others are better with broader strokes or painting the figure. But everyone is encouraged to work on everything. We’re scrambling them around so no painter works on one area, or on one painting. All the while, I encourage them to move slowly, to build slowly. My eyes are on this process the whole time, and I’m constantly checking in and guiding them through it.

JP: In my research on Indigenous textile practices, I have talked about how Indigenous peoples, and women in particular, took European-made goods and ideas and literally ripped them apart, cut them up, folded them into patterns that were meaningful within their own experiences and worldviews, and then stitched them back together. In a lot of ways, that’s what you’re doing. Is your process informed by this kind of thinking?

KM: When I think about how I’m absorbing influence from, say, the Old Masters, I look at their paintings to learn about how they would pose the human body. How did they describe the human body collapsing in grief ? How did they portray ecstasy in a human face? I’m not lampooning their work. I’m trying to understand and absorb the DNA of what great painting is.

JP: What else are you drawing on from the Old Masters?

KM: I’m looking at Western art history as an outsider. I’m a Cree person studying a tradition of painting that began hundreds of years ago and reached its zenith in the nineteenth century. I thought, here’s this grand tradition, which was so capable of storytelling, of presenting narratives, of demonstrating authoritative ideas and themes. It has been discarded by Western art in favor of this individual thinking. I wanted to reclaim it, resurrect it, and find a way to embrace the potential of the language of painting. This can be more than just a brush stroke, more than just explorations of color and texture. Those are only aspects of painting, but that’s a reduced vocabulary. I wanted to harness this very sophisticated language, which is capable of all kinds of nuance, to explore subtle themes and storytelling.

JP: In harnessing this language, you are also opening a dialogue about a central figure, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, who helps you make connections within your work. Miss Chief is a time traveller, a disruptor of historical narratives and colonialist mythologies. In Resurgence of the People, the figure of Miss Chief recalls two works in The Met, Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s sculpture Victory, cast between 1914 and 1916. George Washington is a pretty recognizable reference within many folks’s visual vocabulary, but Victory is not. Can you talk about the choices you made to place Miss Chief within these art historical references?

KM: As I sift through the collection, I look for works that can trigger conversations between colonial or settler works—works made by the settlers about Indigenous people—but I also [think about] how different those points of view are, how foreign those worldviews are from Indigenous worldviews.

When I insert Miss Chief into these works, it’s about challenging the subjectivity of settler artists who often had no idea or very little knowledge about the cultures that they were representing. What we’re looking at is actually a projection of the artists themselves, not real Indigeneity. They were just fantasies; they were romantic ideas that came from books. For instance, Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Hiawatha sculpture in The Met was inspired by the epic, and fictional, poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. There are many things that I see when I look at these works. The Indigenous figures look like they’re in neoclassical poses; they look like Greek gods. There are elements of Christianity in some of them. So, I see more about the individuals and their culture than who they’re supposed to be representing. This is true all the way through to Hollywood westerns.

As I choose the artworks that I riff on, I stitch together conversations about where those artworks are misleading the public, and this is an opportunity in a mainstream museum to confront representations [of Indigenous people] that are often flawed.

JP: How does your work make people think about issues that they might not otherwise realize? Do you have an example?

KM: I think this has happened with many of my artworks, because I’m shattering the illusion of the authority of this one-sided version of a story. It’s so ubiquitous; this singular narrative is everywhere in visual culture. When people see one of my landscapes [that riffs on an Albert Bierstadt painting from the nineteenth century], it might look familiar, yet the narrative inside the painting has been so subverted that it shatters their easy reading of the work. They’re confronted with the possibility that there could be a whole other experience that they’ve never considered. What I’ve been trying to do with the art history of this continent is to break down these myths and fictions that have just impregnated people’s consciousness. The educational systems throughout all the public schools and universities have been blind toward Indigenous experience up until very recently. In Canada, people were never taught about residential schools [government-supported religious schools established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society] and had no idea of the depth and breadth of the policies that the government has perpetuated against us. That’s why I created this mythological being, Miss Chief. With her, I’m able to tell new stories and new mythologies, but also reference real lived experiences and histories.

JP: I find that when you confront your audience with new possibilities, you’re not trying to dictate the way people think, but rather presenting them with alternative realities and histories. You’re also disrupting the notion of Western linear time through the layering of references and characters, as well as through Miss Chief, who appears to transcend time itself. What I appreciate about this diptych and specifically within the Resurgence of the People is that you’re not only drawing on historical works within The Met’s collection, but also using them to imagine possible futures for Indigenous peoples. How do you view time?

KM: I was fortunate in that I had a relationship with my great-grandmother. She died at 101 years of age when I was eleven. She was born in 1875[2], so I feel very close to a history of my own people, but I also feel very close to that period when colonial policies began to be enforced on Indigenous people in Canada. She was a child when these major shifts occurred, when our family was removed from our ancestral lands. That experience seems so resonant with me, so palpable, because I often wonder how different our lives would have been had our land not been taken. I think about it almost every day, how we’ve been treated as second-class citizens on our own land. When I consider her life and the changes that were happening on this continent during her childhood and later, it reinforces to me that we move forward by staying connected to our cultures, to our languages, and to the places that are sacred to us.

European settlers brought their ideas of modernity, their blank slate, here to North America, and they wanted to start fresh, which was great for them, but it came at the expense of erasing Indigenous people. European modernity is a brief period. Indigenous people, when we talk about where we’re from, our cosmologies, we’re talking about thousands of years. Miss Chief is an ancient being. That’s how I like to think about her existence and her relationship to time. It goes back to when the other legendary beings were created. She’s embedded in the Cree worldview.

JP: Speaking of the Cree worldview, can you tell me about the meaning of the diptych’s title?

KM: So, the diptych is titled mistikôsiwak, which is literally “the wooden boat people.” It was a name given primarily to the French by the Cree, but it was also adapted to signify English settler cultures. The title mistikôsiwak refers to settler cultures immigrating to North America. Within the image on the right side of this diptych [Resurgence of the People] it’s the Indigenous people who are now moving forward in this wooden vessel. I like that the word has a relevance to the future as well.

JP: How does titling the project in Cree help to situate Indigenous ways of knowing?

KM: Well, Indigenous ways of knowing are centered in our languages, and I am in the process of reclaiming my Cree language. Our worldview is embedded in our language.

JP: In the description for Welcoming the Newcomers, you use two Cree words that roughly translate to kinship and love. Can you describe them?

KM: Sure, wâhkôhtowin is kinship—relationship with other beings, with nature—and sakihitowhin is love. Those two values are part of Cree laws. The Cree laws teach us as human beings how to get along with each other, but also how to have a relationship with all the other beings—the four legged and the winged creatures—essentially, how we all fit into our relationship to the universe.

JP: In Resurgence of the People, too, the image of the boat and the rising water seems to reference climate change and a future where water reclaims land. I’ve been thinking recently about the idea of relationality and kinship as a way for the global population to move forward. Is that something that you considered in the creation of this work?

KM: Absolutely. I was thinking a lot about water. It was the sea that brought the European settlers here, so both paintings have turbulent seas in them. In Welcoming the Newcomers, it is this pristine Atlantic Ocean. You see settler people from different periods: pilgrims, a conquistador, people clamouring onto the shore. It was oceans that brought waves of immigrants to the continent. The ocean is allegorical for the flood of settlers that displaced Indigenous people from all over North America, including my great-grandmother. When I think about climate change, those rising waters will continue to displace people. I was thinking about migrating populations all over the world.

JP: In this painting, you centre women and their place within many Indigenous communities. Can you talk about why?

KM: I think women have been in terms of the colonial experience. The colonizer came here, and they refused to talk to women. Women were our leaders; women were our lawmakers. In traditional Cree culture, it was the women who made decisions about the land. Through the colonial experience our Indigenous women have been denigrated, and so I’m trying to restore, through my own paintings, the idea that our women are important.

JP: How does the scale of mistikôsiwak help with the goal of restoration?

KM: The genre that I’m working in, it’s history painting, and the tradition of history painting was very much about large-scale paintings. I wanted to paint Indigenous experience, both historical and contemporary, and authorize them into the canon of art history and this genre of painting.

Washington Crossing the Delaware is massive, and the painting has a certain impact because it’s just so big. It commands authority on the museum wall because it takes up almost the whole room. The idea was to give Indigenous experience that same weight. Our histories were erased from this canon of art history. We were relegated to tiny bit players in the landscape. This was a way to centre and foreground Indigenous experience…. People relate differently to scale. There’s something about a large painting and life-sized figures.

With a lot of my artworks I’m exploring these themes from the nineteenth century that reinforce ideas of Native American people as the dying race. With this project, I intercept that notion and refute it by acknowledging that our people are very much alive. Our cultures are thriving and we’re not frozen in time. I’m seeking to dismantle ideas that have been reinforced and perpetuated by museum culture.

All photographs by Aaron Wynia.

Jami C. Powell is the Hood Museum of Art’s first associate curator of Native American art and was recently appointed as a lecturer in Native American Studies at Dartmouth. Powell is a citizen of the Osage Nation and has a PhD in anthropology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Powell’s research examines the representations of Indigenous peoples in museums as well as the interventions contemporary Indigenous artists make through creative acts of selfrepresentation.

Aaron Wynia is a photographer based in Toronto. He is internationally recognized for his youth-inspired portraiture and regularly collaborates with clients and brands in music, fashion, and culture.

___________

Notes

[1] See Jami C. Powell, “Creating an Osage Future: Art, Resistance, and Self-Representation” (PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2018); Jean Dennison, Colonial Entanglement: Constituting a Twenty-First-Century Osage Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012); Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991); Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001).

[2] The Indian Act was introduced in 1876 as a consolidation of previous colonial ordinances and is the principal statute the federal government uses to administer Indian status, and does not pertain to Inuit or Métis. Although the Act has been amended several times—removing particularly discriminatory sections—the statute was aimed at the eradication and assimilation of First Nations peoples into Euro-Canadian society and has enabled human rights violations, trauma, and sociocultural disruption for generations of First Nations peoples. See William B. Henderson, “Indian Act,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, published February 7, 2006, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/indian-act.

Autumn Tigers (Tigres d’automne) de Karen Tam

Jeter un pont entre le passé et le présent : rendre visible l’invisible

Par Imogene L. Lim, Ph. D.

Autumn Tigers (Tigres d’automne) de Karen Tam

Jeter un pont entre le passé et le présent : rendre visible l’invisible

Par Imogene L. Lim, Ph. D.

Les portraits pionniers de C. D. Hoy

Hommage d’un photographe sino-canadien à sa communauté

Par Faith Moosang

Les portraits pionniers de C. D. Hoy

Hommage d’un photographe sino-canadien à sa communauté

Par Faith Moosang

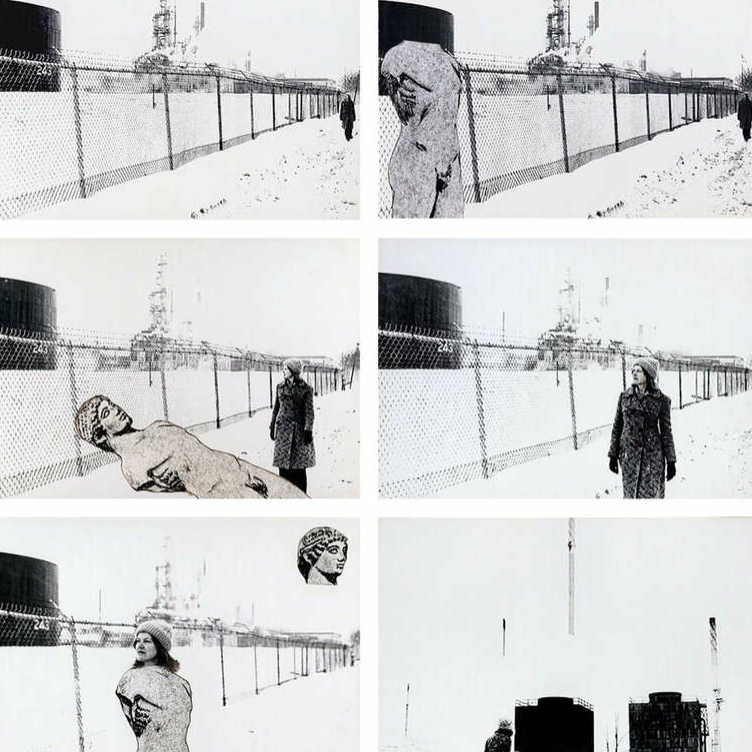

Interroger l’identité

Suzy Lake explore le rôle de la photographie dans la conception que nous avons de nous-mêmes

Par Erin Silver

Interroger l’identité

Suzy Lake explore le rôle de la photographie dans la conception que nous avons de nous-mêmes

Par Erin Silver

Une artiste enhardie

Oviloo Tunnillie parvient à une rare reconnaissance internationale à titre de sculptrice inuite

Par Darlene Coward Wight

Une artiste enhardie

Oviloo Tunnillie parvient à une rare reconnaissance internationale à titre de sculptrice inuite

Par Darlene Coward Wight

Peindre la mosaïque culturelle

William Kurelek traverse le pays dans le but de capter la diversité de ses habitants

Par Andrew Kear

Peindre la mosaïque culturelle

William Kurelek traverse le pays dans le but de capter la diversité de ses habitants

Par Andrew Kear

Mécontentement domestique

Les scènes poétiques de la vie domestique de Mary Pratt sont louées pour leur portée politique

Par Ray Cronin

Mécontentement domestique

Les scènes poétiques de la vie domestique de Mary Pratt sont louées pour leur portée politique

Par Ray Cronin

Une nouvelle vision du Nord

L’art d’Annie Pootoogook offre une perspective inédite sur l’Arctique contemporain

Par Nancy G. Campbell

Une nouvelle vision du Nord

L’art d’Annie Pootoogook offre une perspective inédite sur l’Arctique contemporain

Par Nancy G. Campbell

Communauté d’esprits

Sorel Etrog trouve de nouvelles idées grâce au travail collaboratif

Par Alma Mikulinsky

Communauté d’esprits

Sorel Etrog trouve de nouvelles idées grâce au travail collaboratif

Par Alma Mikulinsky

Présentation de Miss Chief

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art” [en anglais seulement].

Par Shirley Madill

Présentation de Miss Chief

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance: mistikôsiwak (Wooden Boat People) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art” [en anglais seulement].

Par Shirley Madill

Une pratique de guérison

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance” [en anglais seulement].

Par Sasha Suda

Une pratique de guérison

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance” [en anglais seulement].

Par Sasha Suda

Décoloniser la peinture d’histoire

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, « Revision and Resistance » [en anglais seulement].

Par Ruth B. Phillips et Mark Salber Phillips

Décoloniser la peinture d’histoire

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, « Revision and Resistance » [en anglais seulement].

Par Ruth B. Phillips et Mark Salber Phillips

Une vision pour l’avenir

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance” [en anglais seulement].

Par Nick Estes

Une vision pour l’avenir

Voici un extrait de l’ouvrage publié par l’IAC, “Revision and Resistance” [en anglais seulement].

Par Nick Estes

La loi du hasard

La rupture de Jean Paul Riopelle avec l’automatisme

Par François-Marc Gagnon

La loi du hasard

La rupture de Jean Paul Riopelle avec l’automatisme

Par François-Marc Gagnon

De Taos à New York

Agnes Martin en dialogue avec les courants de l’art américain

Par Christopher Régimbal

De Taos à New York

Agnes Martin en dialogue avec les courants de l’art américain

Par Christopher Régimbal

Une artiste prospère

L’esthétique florale de Mary Hiester Reid

Par Andrea Terry

Une artiste prospère

L’esthétique florale de Mary Hiester Reid

Par Andrea Terry

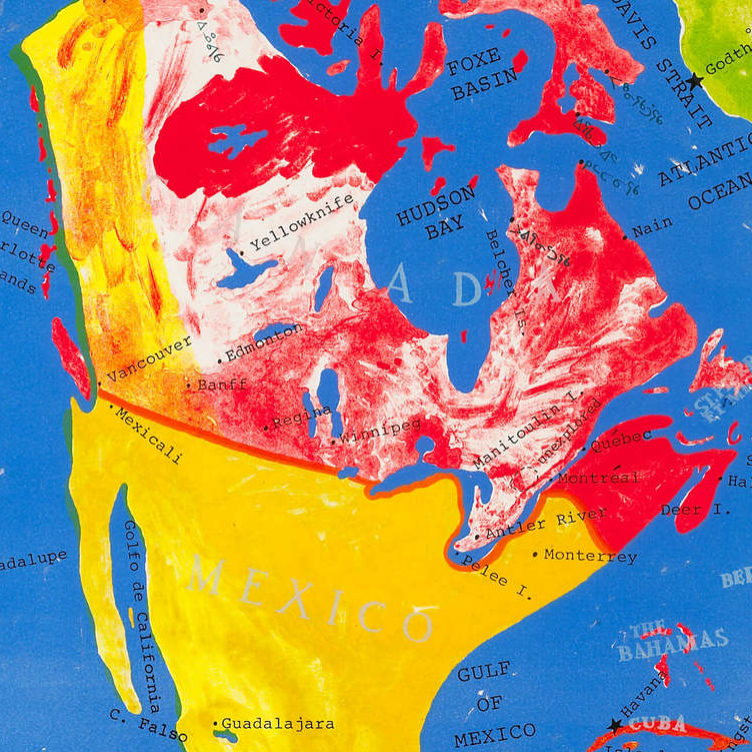

Le peintre patriotique

Le Canada de Greg Curnoe

Par Judith Rodger

Le peintre patriotique

Le Canada de Greg Curnoe

Par Judith Rodger

Marcher, empiler, danser

Les années 1970, ou la décennie conceptuelle de Françoise Sullivan

Par Annie Gérin

Marcher, empiler, danser

Les années 1970, ou la décennie conceptuelle de Françoise Sullivan

Par Annie Gérin

Le nord fabuleux

Le journal paysagiste de Tom Thomson

Par David P. Silcox

Le nord fabuleux

Le journal paysagiste de Tom Thomson

Par David P. Silcox

Un maître de l’abstraction

Jock Macdonald en quête d’une nouvelle forme d’expression en peinture

Par Joyce Zemans

Un maître de l’abstraction

Jock Macdonald en quête d’une nouvelle forme d’expression en peinture

Par Joyce Zemans

Esprit rebelle

L’artiste québécois Ozias Leduc s’appuie sur des influences européennes pour créer un idéal canadien

Par Laurier Lacroix

Esprit rebelle

L’artiste québécois Ozias Leduc s’appuie sur des influences européennes pour créer un idéal canadien

Par Laurier Lacroix